“Immortality brought to Light”: An Overview of Massachusetts Colonial Court Records

IT has been fashionable to describe the colonial period as “the dark ages of American law.”1565 Competent legal historians for this period have been hampered by a dearth of available primary source materials. Now that Massachusetts court records have been largely inventoried, after centuries of being “buried”1566 in courthouse basements, “some way will have to be found for getting scholars and colonial court archives together.”1567

It is hoped that these articles on sources will encourage researchers to use the colonial court records of Massachusetts. They will provide scholars with a county-by-county survey of early court materials in Massachusetts, jurisdictional outlines of the courts, a glossary of commonly used legal terms, a guide to common law rules of pleading and procedure, and discussions of data contained in the court records for non-legal historians. There are also listings of relevant primary and secondary materials at four major research institutions in Massachusetts for colonial legal studies.

The publication of these articles on sources is not the Colonial Society’s first attempt to lead researchers to court records. In addition to publishing the excellent early volumes of Massachusetts court records, one of the Society’s prominent early members must be credited with the conservation of a collection which has been variously described as “a legal and historical treasure”1568 and “the best single collection”1569 of colonial court records in the country. John Noble, Clerk of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts and Editor of Publications for the Colonial Society at the turn of this century, directed the conservation and indexing of these files between 1883 and 1907. Generally known as the Suffolk Files, the collection comprises minute books, extended record books, and 1,289 volumes of file papers, mostly from the Superior Court of Judicature. It also includes other miscellaneous papers from County Courts, the Court of Assistants, General Sessions, Common Pleas, and Admiralty. Located in the Office of the Clerk of the Supreme Judicial Court for Suffolk County, fourteenth floor, Suffolk County Court House, Boston, the Suffolk Files have adequately been described by Noble and other scholars.1570

Discussing the custodial provenance of these papers and records in an 1897 article, Noble observed that “one of the [clerks] cared little for such accumulations of the past, the other cared much.”1571 Thus, Noble unwittingly explained why most of the Commonwealth’s colonial court records have received little custodial attention over the centuries, while several select collections have received considerably more. This fact was amplified by an incident more than half a century later. In 1954, Elijah Adlow, then Chief Justice to the Boston Municipal Court, was informed by the clerk’s office that there was desperate need for space and that the “rubbish” in “an old vault in the basement” should be burned. Adlow was then led “down into the dark, cavernous basements of the old building” where he discovered, much to his “amazement,” nearly thirteen thousand papers from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Among these “crumbled and dust ridden sheets,” Adlow found a complete set of quarterly returns of the Suffolk County Jailer for the period 1770 to 1820, listing prisoners confined there during the entire Revolutionary period. There was a voucher written by Sheriff Frobisher certifying his outlays for lodging and “victuallying” the jury that tried Captain Preston and other participants in the Boston Massacre. There were also records of Justice of the Peace Stephen Gorham, minutes of the Court of General Sessions for Suffolk County, and complete files of the Town Court of Boston, a tribunal unknown to any of Adlow’s contemporaries.1572 The Adlow Collection is now at the Boston Public Library.

It should be noted that “the old courthouse” to which Judge Adlow had referred was also the seat of the Supreme Judicial Court in Boston, the very same building in which John Noble had served as clerk over a half century earlier, and is still in use. Recently, and again in the same building, the Librarian of the Social Law Library, Edgar J. Bellefontaine, saved from destruction the file papers of the Suffolk Inferior Court of Common Pleas for the period 1730–1817. Beginning in 1976, the Social Law Library sponsored a four-year Project to organize and conserve the over 360,000 file papers, minute books, and extended record books. In so doing the Social Law Library publicized the need for preservation of such papers, which for centuries had been stored in precarious conditions in courthouse cellars throughout the Commonwealth.

Also in 1976 the Honorable Edward F. Hennessey, Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court, appointed a Judicial Records Committee composed of clerks, scholars, librarians, and archivists. The Committee was mandated to appraise the condition of the Commonwealth’s judicial archives and formulate enlightened records management and archival policies. A number of projects have been undertaken, including an inventory of records of the Superior Court and its colonial predecessors. That inventory, the relevant parts of which are published in this volume (see below, 531–540), identified court records throughout the state which “have been in storage, unused, for up to 350 years. . . . Many records are in such fragile shape that to use them without proper precautions would be tantamount to destroying them.”1573 There are now plans to collect and centralize all the pre-1859 materials in a special judicial archives section of the Massachusetts Archives building now under construction. Moreover, under the leadership of Chief Justice Hennessey, the Social Law Library’s professional conservation laboratory and its staff of conservators and archivists have been adopted by the Supreme Judicial Court as the nation’s only official court records preservation and management facility. Chief Justice Hennessey has thus committed the Supreme Judicial Court to continue this “Noble” enterprise.

Scholarly Neglect in the Past

With relevant records kept for centuries in the kind of “dark” basements to which Judge Adlow alluded earlier, it is understandable why the judicial history of the colonial period has been dimly understood for so long. Unfortunately, the lack of research into legal records themselves has led to erroneous explanations about law in the colonial period—erroneous explanations which exert enormous influence and which persist to this day.1574 Roscoe Pound popularized the misconception that under colonial conditions there was only “a rude administration of justice.”1575 The title of his famous book The Formative Period of American Law (Boston, 1938) (referring to 1775 to 1860) has become accepted in the lexicon of our legal history to mean that “[f]or most practical purposes American judicial history begins after the Revolution.”1576 Adjudication, asserted Pound, was left to “untrained magistrates who administered justice according to their common sense and the light of nature with some guidance from legislation.”1577

Thus several generations of scholars were dissuaded from delving into serious studies of law during the colonial period.1578 Pound’s view became the established view, which to some extent still endures. Grant Gilmore, for instance, in his relatively recent book The Ages of American Law (New Haven, 1977), reflects a similar misconception concerning colonial legal studies:

[T]here can hardly be a legal system until the decisions of the courts are regularly published and are available to the bench and bar. Even in the seaboard colonies, where the practice of law had, during the eighteenth century, became professionalized, there were no published reports; consequently there was nothing which could rationally be called a legal system.1579

One of the first uses of court records is to test such theories against the true record of our colonial tradition. The work of George Haskins and others has taught us that to learn the facts of our colonial legal heritage we must unlearn such fictions as that there was “nothing which could rationally be called a legal system.”1580 Gilmore’s logic overlooks the work historians have done in tracing the development of colonial doctrines from “unpublished judicial opinions, lawyers’ notes, and, most commonly, records of pleadings, judgements, and other papers incorporated into official court files.”1581 Although decisions of the colonial period were not regularly published, they were regularly recorded. In all Massachusetts counties, clerks from the Superior Court of Judicature, Courts of Common Pleas, and Courts of General Sessions kept extended record books, sometimes called judgment books, in which clerks summarized transcriptions of parties’ pleadings and motions, the juries’ verdicts, and the courts’ judgments. In this context it should be noted that although there were no published court reports until after the Revolution, lawyers did, on occasion, prepare and circulate among themselves collections of local cases.1582 For more detailed information scholars are turning their attention to file papers to trace changing practice styles, which in turn substantiate changes in substantive law. The articles published in this volume often demonstrate the use of such records and the relative sophistication of the legal system they represent.

Scholars like William E. Nelson are finding that important “formative” doctrinal developments of the nineteenth century actually had important antecedents before the Revolution. For example, the development of a generalized negligence theory in torts superseded the particularized and technical pleadings of the common law writ system. The “conventional explanation” for the demise of the writ system is that the nineteenth-century codification movement suddenly abolished the writ system’s forms of actions.1583 Specifically, scholars have identified the 1848 enactment of David Dudley Field’s New York Code of Civil Procedure as the “catalytic agent” which, almost “at one blow,” pronounced “the death sentence” on common law pleadings.1584 “Unfortunately, insufficient scrutiny of the writ system has taken place to justify this conventional explanation.”1585 In fact, Nelson’s study of common law pleadings in Massachusetts suggests that the reform was gradually modified over a long period and that, when the state legislatively abolished writ pleading in 1851, the reform was already realized in practice.1586

Colonial records may also help to explain the development of the consideration doctrine in contract law. Some scholars, such as William E. Nelson and Morton J. Horwitz, have suggested that eighteenth-century common law courts discouraged competitive commercial transactions through an analysis of what in essence was consideration, whereby agreements were scrutinized for substantive equality of the exchange.1587 Such a mechanism for policing the fairness of exchanges may have protected the unsuspecting against bad bargains, but could have been a burden to the burgeoning business interests of the late eighteenth century. Horwitz has suggested that businessmen apparently “endeavored to find legal forms of agreement with which to conduct business transactions free from the equalizing tendencies of courts and juries. Of these forms, the most important was the penal bond.”1588 Such bonds “precluded inquiry into the adequacy of consideration for exchange”1589 and “allowed parties to determine their own damages free from judicial intervention.”1590 Except for this general overview of the use of penal bonds, we must await more detailed, empirical studies of court records to explain more fully the influence of penal bonds on the judiciary’s changing concern away from the adequacy of consideration to a non-protective inquiry confined to the presence of mere formal consideration. As David H. Flaherty has pointed out, for “the colonial era . . . civil litigation remain[s] almost unstudied.”1591

Early court records can also help scholars to evaluate the impact or implementation of legislation. Two examples come to mind. Some scholars have speculated that the passage of the Stamp Act may have hindered the developing practices of young lawyers, and thus in some measure may have encouraged these young men to revolt—a difficult action in an otherwise conservative profession which teaches reverence for law, not revolution.1592 Young John Adams was anxious and annoyed by the whole affair:

So sudden an Interruption in my Career, is very unfortunate for me. I was but just getting into my Geers, just getting under Sail, and an Embargo is laid upon the Ship. Thirty Years of my Life are passed in Preparation for Business. I have had Poverty to struggle with—Envy and Jealousy and Malice of Enemies to encounter—no Friends, or but few to assist me, so that I have groped in dark Obscurity, till of late, and had but just become known, and gained a small degree of Reputation, when this execrable Project was set on foot for my Ruin as well as that of America in General, and of Great Britain.1593

What exact impact did the Stamp Act have on the careers of Adams and others, as well as on the courts generally?1594 Did fewer lawyers begin practice during the year the Stamp Act was in effect? How many fewer cases did Adams handle in court, or, for that matter, how many fewer cases were generally heard?1595 Given that geographically there were whig and tory strongholds within the colony,1596 did the Stamp Act affect lawyers and courts in different counties differently? Court records provide empirical data from which to make term-by-term, year-by-year, and county-by-county comparisons.

Such examination of early court records is essential with respect to understanding the implementation, as well as all the implications, of various other legislative initiatives. The plight of Tory property demands such a look at litigation. The loyalists who fled Boston at the beginning of the American Revolution left their lands—and indeed their beloved homes—at the mercy of the very patriot leaders and neighbors who forced their departure. In 1779 the General Court passed two confiscation bills. The first was “An Act to Confiscate The Estates of Certain Notorious Conspirators.” (Acts & Resolves, v, chap. 48, 966–967.) Punitive in nature, it confiscated without any legal process the estates of twenty-nine notable loyalists.

The second, less vituperative bill was aimed at a wider class of “certain persons commonly called absentees.” (Acts & Resolves, v, chap. 49, 969–971.) Ostensibly it aided the state’s coffers and creditors by establishing a judicial procedure for the condemnation and sale of Tory estates, under which the attorney general issued a complaint in the inferior courts of common pleas. In addition to interesting tidbits (John Adams’ country seat in Quincy, “Peacefield,” was a confiscated Tory estate), research in the court records has revealed, to one scholar at least, “an inside story of corruption, self interest and plunder in Massachusetts’ confiscation policy.”1597 Despite concepts of due process envisioned in the legislation, its implementation tells a rather sordid story. The lesson for historians is that public policy may be enunciated by the legislature but, as revealed by court records, can still be undermined by the judicial process.

The Records Series

Court records consist of three distinct record series: minute books, extended record books, and file papers. All students of colonial law should be aware of these record types, their relation to one another, and the kind of information which can be gleaned from them. The following generalized description is drawn from the Suffolk Common Pleas court records, since no chronological or colony-wide comparisons of clerks’ practices have been undertaken. In fact, as noted by the editors of the Legal Papers of John Adams, there is still “embarrassingly little knowledge of the way in which the Massachusetts courts regulated their business and conducted their trials.”1598

38. Colonial Court records of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk. Illustrated are a minute book, a record book, and file papers. In other counties, colonial file papers are still in their original case rolls. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

Clerks regulated their court business primarily through the use of minute books, and they constitute the only index to the file papers. Somewhat like the docket books of today, minute books recorded basic information about the court’s work load. Although a single minute book may sometimes cover a period of more than a year, they are organized by four terms most frequently held in January, April, July, and October. The first page for each term would indicate the day and month beginning the term, identify the sitting judges, and usually enumerate the first and second petit juries then serving.

Civil cases are listed by ascending number in a typical plaintiff versus defendant fashion. Some clerks in some years meshed the continued actions of previous terms in the same numerical sequence, while other clerks in other years maintained separate continued action lists. It should be noted that the minute book number corresponds to the case number for that term and would be written on the back side of the writ. In the event of a continuance, the case papers were held and grouped with the cases for the next term; the old number was scratched out and a new minute book number assigned. Thus some cases with multiple continuances will have numerous scratched-out minute book numbers, by which one may trace the case back to earlier terms.

In the right margin of the common pleas minute books, the plaintiffs’ attorneys are listed. The early books generally do not mention any pleas, while some of the nineteenth-century books do. Minute books do mention, however, the determination of cases in a shorthand, skeletal fashion. Also it was not uncommon for referees to be appointed, and clerks would indicate this in similar cryptic fashion. The left margin seems to have been kept clear for post-trial filings, most often executions and appeal bonds.

On the last page of the term the clerk customarily indicated the date court adjourned, as well as special court business. It was not unusual for the clerk to note the swearing in of attorneys, or to take minutes of special motions, or to post new rules promulgated by the court. The last pages of the 1738 July term of the Suffolk Inferior Court of Common Pleas indicate that the justices entertained a number of oral motions for fees and costs. For example, “The Memorial of Robert Auchmuty and others, . . . relating to the allowance of their fees having been considered by the Court was not granted they being divided in their opinion concerning the same.” Perhaps impatient with such motions, the court ordered “that henceforth all motions for costs shall be made in writing & the like fee be paid to the court as for other complaints.” As their last act in 1738, the justices levied new fees, which were to be split between the court and the clerk, on “proving a deed in Court.”

In addition, minute books provide much statistical and procedural information about the business of the court. They record the length of terms, the number of cases handled, the frequency of referring cases to referees, the number of continuances, court rules ordered by the justices, the frequency of appeals, and the levels of practice of particular lawyers.

Although skeletal in nature, these minute books tell who was in court and how often. In fact, biographers are beginning to believe that court records are of “extraordinary value.”1599 A brief look at the lawyers and litigants on the final page of the 1758 minute book for the Suffolk Inferior Court of Common Pleas offers a remarkable example. In a few brief entries we find Jeremiah Gridley, tutor to such as John Adams, James Otis, and William Cushing, was involved as a plaintiff representing himself. Two signers of the Declaration of Independence, Robert Treat Paine and John Adams, are present in court as well. Paine was participating as a plaintiff in a minor civil case; Adams and Samuel Quincy were beginning distinguished careers at the bar as they were “admitted as Attorneys in Law in this Court to Act as Such and accordingly tooke the Oaths of an Attorney.” The session is presided over by Foster Hutchinson, brother of the royal governor driven into exile by the Revolution that Paine and Adams helped to start.

39. Docket Book, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1758 October, showing the admission of John Adams and Samuel Quincy as attorneys on 6 November 1758. Note the signature of Ezekiel Goldthwait, Clerk, and the names of Jeremiah Gridley, Foster Hutchinson, and Robert Treat Paine. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

Clerks also maintained extended record books. These are large folio volumes, sometimes called judgment books, and constitute the formal, official record of the courts’ actions on adjudicated cases. They are arranged in yearly volumes with plaintiff name indices and page reference numbers at the beginning of each book. They are not cross-referenced to the minute books or the file papers, since the order of entries is according to the courts’ final actions. They also do not reflect the flow of court business, as they record only adjudicated cases. They do, however, provide an important summary of each case and mention the parties’ names, places of residence, and occupations or professions. This is important demographic data, which is clearly set forth and easily coded for computer analysis. These records also summarize the legal written pleas and oral pleadings of the facts of the cases. They provide the courts’ final determination of cases and also indicate when executions were issued and whether appeal bonds were filed. This information overlaps that of the minute books to some extent, especially with respect to the end-of-term orders of the court.

The Suffolk County Court of General Sessions displayed a respect for its records in its decision to replace the courthouse of 1764–1766 with a new building designed by Charles Bulfinch in 1810. In reaching its determination to build a new courthouse, the general sessions justices heard the following report, noted in the 1807 extended record book. “The Committee beg leave further to report that from the increase of population in the Capital and the accumulation of business in the Courts, it is no longer possible for the various courts to do their business in one small Court House (besides further provision ought to be made for public offices and for securing public papers.)”1600 As a historian of this Bulfinch building cleverly noted, “the corset could no longer hold the body.”1601

The extended record books are the easiest records series to use since they are sturdy and well bound and generally complete. Many minute books are extant, but these quarto waste books are much more fragile. File papers, to be discussed below, are the most difficult to use but also the most promising. Except for the Suffolk and Essex Files, most extant file papers have been left exactly as they were soon after adjudication. It was the practice of clerks to fold file papers in tripartite, bundle and label them by term and year, and tie them with linen string into case rolls. Subsequent clerks stuffed these upright into the same cramped topless file tins in which they survive today. “As we take the court documents from their original packages,” Hiller B. Zobel has observed, “we literally unfold our history.”1602

The Documents

The documents have great intrinsic historical value. Catherine Menand, Chief Archivist of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, notes that “the sheer aesthetics of these early documents are important independent of their content and they provide a source of cultural and technological history.”1603 For example, documents were demanded at every stage in the legal process, but paper was often in short supply. By examining watermarks—the papermakers’ unique signatures or trademarks—one can trace the importation of paper as well as the establishment of local mills. Paper from England dominates the Suffolk County Inferior Court collection, but there is also paper from France and Denmark. A look at English and American watermarks shows the differences and disparities between old England and New England. Generally speaking, English watermarks are majestic crests, sometimes shield-shaped, with ornamental ridging and armorial bearing. Early American papermakers relied on simpler symbols, almost primitive when compared to their English counterparts. They pictured plows and Indians, doves, with and without olive branches, and eagles.1604 One telling watermark simply states “Save Rags”—a plea about the near-constant shortage of the raw material necessary for the manufacturing of rag paper.1605

40. Watermark, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1790 OCT c. 288. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

41. Watermark, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1797 OCT 88. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

Watermarks are clearly visible only when paper is held to light. Thus they can sometimes hide, or heighten, historical ironies. For example, on 1 May 1776, two full months before the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia, the Massachusetts General Court ordered that all legal papers, processes, and proceedings no longer mention the monarch’s lengthy title: “George the Third, by the Grace of God of Great Britain, France and Ireland, KING, Defender of the Faith, etc.” (See illustration below, 544.) Soon thereafter, in Suffolk County, either the clerks of court or lawyers unceremoniously scratched out, by hand, the foregoing title from writs and other formal papers and wrote in its place: “The Government and People of the Massachusetts Bay in New England.”1606 Massachusetts may have declared its independence from the mother country, but as the manuscripts are held to light, and English watermarks are overwhelmingly revealed, it shows that the colony’s legal process still very much depended on English paper.

The records have other interesting physical features. Embossed filing stamps were not uncommon on bonds, indentures, and other documents. Designs on provincial filing stamps, for example, were derived from important economic resources and appear to have remained constant for long periods: a cheerful codfish with the motto “STAMP OF THE MASSACHUSETTS” on the tuppence stamp; a flourishing pine tree on the three-penny stamp with the motto “PROVINCE OF MASSACHUSETTS” 3 and a trim two-masted schooner with the motto “STEADY—STEADY” on the four-penny stamp.1607

42. Embossed four-penny filing stamp, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1771 OCT c. 49. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

43. Embossed tuppence filing stamp, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1761 JAN 128. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

44. Heraldic embossed seal of Richard Jenneys “Notary & Tabellion Publick by Royal Authority . . . in Boston,” Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1760 OCT 134. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

45. Embossed three-penny filing stamp, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1755 OCT 173. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

An amazing variety of intricate, rich, red-wax seals has survived on the surfaces of these documents. They provide visible and tangible evidence of a person’s stature and authority. Public officials frequently assumed a heraldic coat of arms as their seal, as did merchants and other wealthy and worldly persons. The papers bearing these seals provide excellent evidence documenting British mercantile connections within the empire. Decorative monograms, rebuses, unmarked tabs of paper, ink marks—even finger prints—were used by less eminent persons not entitled to coats of arms.

The variety of such seals makes a most interesting study, and as with watermarks, understanding sometimes unveils otherwise hidden ironies. The embossed, heraldic seal of Richard Jenneys “Notary & Tabellion Publick by Royal Authority duly Admitted & sworn dwelling and Practicing in Boston” shows as his crest a hand clasping olive branches surmounted by an eagle erect.1608 Hugh Clark’s Short and Easy Introduction to Heraldry (London, 1788) defines these “technical terms” thus: “Hands signify power, equity, fidelity and justice”; the “olive tree is the emblem of peace and concord”; and the “Eagle is accounted the King of birds, and signifies magnanimity and fortitude of mind, who seeks to combat with none but his equals.” Another seal, the crest of a swan, according to Clark’s Introduction to Heraldry representing “Appollo’s bird, the emblem of sincerity,” ironically appears on Malachy Satter’s unpaid promissory note of 1778.1609

Artistic engravings also adorn many of the merchant accounts entered as evidence in actions to recover unpaid bills. Patriot and silversmith Paul Revere was an engraver too. “He was especially fond of elaborate Chippendale borders and mantling and evidently copied the designs of English cards. [How unpatriotic!] . . . But few of Revere’s cards have survived to the present day. Of a dozen or more which he is known to have engraved, only five are to be found, four of them unique examples.”1610 Another of these rare Revere engravings, a billhead, has turned up in the Suffolk common pleas papers. It is a profile engraving of “O. Cromwell’s Head,” the symbol of Joshua Brackett’s well-known inn located on School Street.1611

Other engravers, perhaps less renowned than Revere—even obscure to the point of anonymity—often applied their artistic skills to merchant billheads preserved in early court papers. Some engravings visually explain work processes and expound patriotic sentiments in the years immediately following the Revolution. The billhead of Eben Clough’s “Boston Paper Staining Manufactory” illustrates the basic steps in wallpaper making during the eighteenth century while, at the same time, proclaiming “Americans, Encourage the Manufactories of your Country, if you wish for its prosperity.”1612 The picture depicts the actual production processes of early wallpaper making. Catherine Lynn Frangiamore’s Wallpaper in Historic Preservation explains:

[T]he gentleman wielding a large brush in either hand is laying on the ground color. Immediately to the left of the tablet describing the business, a printer with his left hand under the handle on a carved woodblocks raises a mallet with his right hand to strike a firm impression. The boy standing to his left prepares the color between each impression, spreading it on a pad. The man of the far left, with the assistance of yet another boy, is probably rolling and trimming paper in standardized lengths for sale.1613

Of course the colonial and early republican court papers are primarily valuable for their contents, not their aesthetic character. An exhaustive survey of each and every document type, litigant, and legal plea is beyond the scope of this paper. But a sample from a single term should be enough to encourage further examination, especially with the other articles on sources as research aids. Take, for example, the 1765 July term of the Suffolk County Court of Common Pleas. Most of the actions are of first instance in the inferior court, although there is at least one judgment on appeal from a justice of the peace and several litigants suing on executions from earlier, yet unsatisfied, judgments.

46. Billhead, engraved by Paul Revere, Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1772 JUL Misc. Joy v. Brackett. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

47. Engraved billhead illustrating the basic steps in making wallpaper. It encourages customers to buy American goods. See above, 490. Inferior Court of Common Pleas, Suffolk, 1801 APR c. 380. Courtesy, Social Law Library, Boston.

Every court term saw luminaries involved in litigation. For instance, Samuel Adams was involved in several suits during the July term of 1765. In at least three separate actions he was acting in his official capacity as “a Collector of Taxes” for the years 1759 through 1763. Defendants in these actions were “Jack a free Negro,” and housewrights William Moor and Samuel Avery.1614 Each was in arrears for several years on their ratable “proportion of Province County and Town taxes,” which Adams’ declarations detailed in exact amounts. Adams’ attorney in each action was James Otis, Jr., that famous “flame of fire” who argued in the great Writs of Assistance Case of 1760. There is no evidence from the file papers that defendants Moor or Avery were represented by counsel, but “Jack” was represented by Samuel Fitch. Otis found authority for the actions “by force of an Act of this our Province made in the forth Year of our Reign entitled an Act to enable . . . Collectors of Taxes in the Town of Boston to sue for and recover the Rates & taxes given them to collect in certain Cases. . . .”

File papers generally do not, in themselves, record the results of these suits, although in some cases there are jury slips indicating judgments. Scholars must turn to the extant extended record books and minute books. The papers do, however, provide important information from a number of perspectives. There is both personal and professional biographical significance. Thus, these records reveal a long-term professional relationship, as between the two famous patriots, tax collector Adams and lawyer Otis. Further, Otis’ reliance on legislation as authority on which to maintain the litigation may help to show the state of trial practice, as well as illustrate the general background, influence, and impact of this tax-related act. Adams’ actions and Otis’ arguments to enforce these taxes passed by the provincial legislature are in contrast to the revolutionary cry “no taxation without representation.”

Government agents like Adams were not only plaintiffs, but sometimes defendants too. The “Proprietors of the East & West Wings so called the North half of the Township of Rutland in our County of Worcester” were sued in 1765 by Stephan Minot, administrator to the Estate of Jonas Clark, Esquire. It seems that Clark “by a Vote of the Proprietors was appointed and at their Special request became their Clerk . . . during [which] . . . time [he] faithfully served them in that Office and trust, duly attended their several meetings, kept their books & accounts & regularly entered all their Notes and orders and their Planns and Surveys and transacted their business abroad. . . .” Clark’s administrator claimed that he was never paid for the foregoing services, some of which were detailed in an attached account. Such details provide valuable insights into the administration of colonial government.1615

Litigants throughout these records came from all counties, colonies, and points of the compass. Especially interesting are the cases relating to the sea. Boston’s waterfront swarmed with wharfingers, coasters, and shoremen, as well as boatbuilders, shipwrights, ship carpenters, caulkers, mastmakers, blockmakers, ropemakers, riggers, sailmakers, oarmakers, and carvers. All appeared in the court records, as do the mariners, sailors, officers, and pilots manning these ships. Their cases touched upon complex issues, issues as diverse as impressment, articling of underage seamen, wages, and cargoes lost to privateers and storms. Such cases connected Boston to points of call in Africa, South America, the Pacific Northwest, the East Indies, and China.

The 1765 July term had several controversies related to seagoing and international commerce. Robert Robins, “Master of the Good Schooner called the Polley,” sued “Daniel Arthur of the City of Lisbon in the Kingdom of Portuagal Merchant” for breach of a written covenant.1616 The agreement was recounted in the declaration of Captain Robins’ writ of attachment and was drawn by another famous lawyer, Josiah Quincy. It described a trade route, import and export goods, and the voyage’s expected time and pay schedules. Robins claimed that the outward cargo of wine and fruit was delivered pursuant to the agreement to Boston via Halifax (“the wind not proving favorable”), but Daniel Arthur’s agents broke the agreement by not having a required cargo of fish ready to return to Lisbon. For this Robins asked judgment of four hundred pounds.

“Landlubbers” in commerce appeared in court records too. “Historians would learn far more about economic life in Boston from an analysis of the civil court records of the Superior Court or the Suffolk County Court, than from almost any extant efforts at writing the economic history of this community.”1617 Currency shortages were not uncommon. Although some colonists tried counterfeiting, most relied on each other for liberal credit or were content with poor commerce. Despite signed bonds and promissory notes with compound interest, debtors were often dilatory, and creditors demanded payment in their formal “pleas of debt” filed in the Inferior Court of Common Pleas. If no bonds or promissory notes had been extracted from debtors, creditors often had detailed accounts of sales or services which corroborated their “plea of the case” claims. Such accounts accompanied the more formal legal papers and revealed much detail about colonial life.

In addition to the accounts and inventories which preserved the external details of colonial life, other documents immortalized the personal sentiments, the spirit, and even the speech of litigants centuries dead. Depositions, now called affadavits, told harrowing tales of human travails. For example, the rambling deposition of John Martin Randell recounted his voyage, as boatswain, “on board the ship Ulysses . . . David Lamb Commander . . . some time in the Month of August 1798 Bound from Boston to the North West Coast of America, from these to Canton and back to Boston. . . .” It seemed that at the voyage’s very beginning the commander tried to dispel his cantankerous reputation “the first Night after we made Sail, When We Was about oposite the Ligh[t] House in Boston Harborer the Capt. Called All Hands, Officers and Men aft . . . and informed them that he had been formerly called a Tyrant, but now he was going to alter his conduct and behave better . . . and everything seemed to past. Harmonious until we arrived at St. Iago.” There the captain “left one half of the people go on shore at a time that they might buy some . . . stores. . . .” But the captain began to show how little he cared for his crew when one sailor, Charles Reed, did not return. “We went on board the Ship, all Hands were ordered to Supper, directly after Supper [the first mate] asked if all Hands were on board. . . . he was told that Charles Reed was left on Shore, [the first mate] then asked Capt. if he Should Send a boat on Shore for Charles Reed? No Sd the Capt. if My own Father was on Shore I would not send for him, . . . then the Capt. ordered . . . Charles Reed’s Chest and Baggage aft into the cabin to him which was done, and his Chest was Opened directly and things were all overhauled, and some Money was found in the Chest which the Captain took. . . .”

During the passage from St. Iago to the Falkland Islands, “Our allowance of Provisions was . . . diminished daily, Until it became so Small, and our Duty so hard” that the crew began to complain. There were several savage episodes, including the beating of the carpenter “to Such a degree that he was all over Bloody, and brused very much, and almost out of his Sences . . .” merely because “the Bread-room door was loose. . . .” On another occasion, “While we were heaving at the Windlis the Hands were so exhausted for want of Sleep and refreshing, and some with sore throats that they could not Sing out While heaving and the Capt. said Why don’t you Sing . . . and then he called for his pistols . . . and walked forward within about Seven or Eight passes of where we were . . . and Stopt and cocked his pistols and he Leveled them at our Heads, and said if you don’t heave up . . . I will blow your brains out. . . .” Relations between Captain and crew deteriorated as the Ulysses “passed from the Falkland Islands round Cape Horn.” Randell’s deposition describes episodes on the voyage for eight pages. Finally, at one point, “the Capt. kept up his tirannical behavior to such a degree and being intoxicated by Liquor at the same time, that the whole crew were afraid for their lives, and two days before we came to anchor they were obliged to confine him, to save their own lives . . . ,”1618 Thus, the captain was imprisoned by his crew!

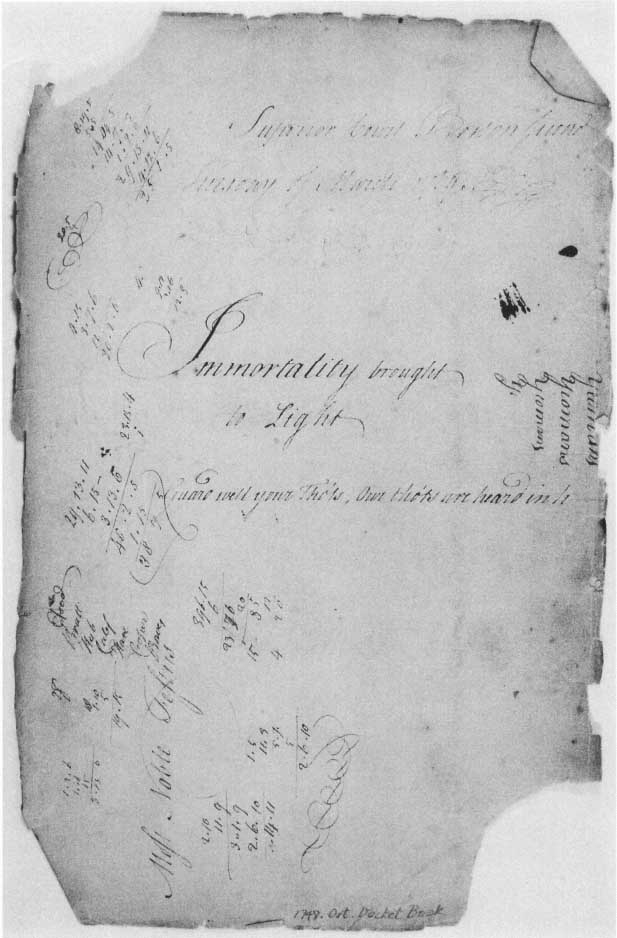

There are many depositions among court documents which, like that of boatswain Randell, narrate misbegotten thoughts, words, and deeds. In litigation, as in life, we all must wonder what unknown witnesses are listening or looking on. One unknown court clerk must have been harboring such paranoid thoughts when he wrote, in large and florid pen strokes, the following inscription on the title page of the minute book for October 1748: “Immortality brought to Light” Court records do bring the “dark ages” of colonial law to light, and will immortalize men and women long since dead. But our clerk was concerned with judgment day in another court, the court of very last resort: “Guard well your Tho’ts” he added, “Our tho’ts are heard in h———.”

Conclusion

James Willard Hurst has declared that “[t]he greatest difficulties for legal history lie in relating the formal operations of law—passing statutes, deciding cases, making administrative orders or rules—to the life that flowed outside the legal forms.” He called for a “hyphenate legal history: legal-economic history, legal-religious history, legal-class-and-caste history.”1619 In other words, legal history should no longer divorce doctrine from day-to-day living. In this context court records help reconcile law with the rest of life. They reflect not only the final solutions of judges and juries, but also the initial human problems of people suing over matters of personal concern. Much can be learned from cases involving common yeomen, carvers, coopers, confectioners, cordwainers, butchers, bakers, housewrights, husbandmen, tailors, weavers, hatters, periwigmakers, doctors, distillers, dancing masters, mathematical instrument makers, and myriad others who make up the mosaic of colonial life. Almost as if anticipating Hurst’s “hyphenate legal history,” John Noble noted 1897 that court records “are something of a study in government, economics, sociology, education, religion, politics, public and private life.”1620

1 Edmund S. Morgan, The Birth of the Republic, 1763–1780, Revised Edition (Chicago, 1977), 4.

2 Roscoe Pound, The Spirit of the Common Law (Boston, 1921), 113. See also Pound, The Formative Era of American Law (Boston, 1938), 3–8.

3 “The Body of Liberties of 1641” from The Colonial Laws of Massachusetts, W. H. Whitmore, ed. (Boston, 1889).

4 See Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar (Boston, 1911), 73.

5 See Dennis R. Nolan, Readings in the History of the American Legal Profession (New York, 1980), 2.

6 Barbara A. Black, “Community and Law in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts,” Yale Law Journal, xc (1980), 246, reviewing David T. Konig, Law and Society in Puritan Massachusetts (Chapel Hill, 1979). This is not to say law was always the only, or dominant, form of social control, but that it was always a substantial form of social control. Daniel Boorstin put it particularly well. “The Colonists, though not lawyers, were of a decidedly legalistic turn of mind. . . .” Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Colonial Experience (New York, 1958), 20.

7 See George Haskins’ seminal book, Law and Authority in Early Massachusetts (New York, 1960), 1–8. “Few others equaled [Massachusetts Bay’s] contribution to theology, letters, and education; none paralleled its early achievements in government and law.” Ibid., 1.

8 Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (New York, 1973).

9 S. E. Morison, “Preface,” The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxix (Boston, 1933), ix.

10 See Stanley N. Katz’s bold and stimulating “The Problem of a Colonial Legal History” in Colonial British America, Jack P. Greene, J. R. Pole, eds. (Baltimore, 1984), 457–484; and David H. Flaherty’s excellent “Introduction” to his Essays in the History of Early American Law (Chapel Hill, 1969), 8–17.

11 As Flaherty puts it, “The field is not barren . . . yet it has not yielded a bountiful harvest.” Ibid., 14.

12 Stephen Botein, Early American Law and Society (New York, 1983), 1. See also S. E. Morison, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxix, ix.

13 See Stanley N. Katz, “The Problem of a Colonial Legal History,” 478. Katz believes contemporary ideological disputes could also be “diversions from the main task of understanding the past.” Ibid. Cf. Charles M. Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History (New Haven, 1938), iv, 222–223, n.1.

14 Stephen Botein, Early American Law and Society, 1.

15 See George L. Haskins, Law and Authority, x–xiii; James W. Hurst, Law and the Conditions of Freedom (Madison, 1967), 4–9; David T. Konig, Law and Society, xiii.

16 Cf. Perry Miller, “Errand into the Wilderness” from Errand Into the Wilderness, P. Miller ed. (New York, 1956); The New England Mind (Boston, 1953), ii, 130–131; and The Life of the Mind in America (New York, 1956), 99–116. Cf. Lawrence M. Friedman, “Heart Against Head: Perry Miller and the Legal Mind,” Yale Law Journal, lxxvii (1968), 1244–1259, reemphasizing the need to study legal ideology in a social context.

17 This, of course, does not denigrate the need for “conventional” legal expertise. “The fact that many ‘legal scholars’ do not explore extensively the social background and context of legal conflict leads some to think that their works say nothing about ‘law and society.’ The tendency is to put these books in their place: excellent reference books on rules, not roles. But even the narrowest of these works may contribute substantially to one’s understanding of the role as well as the rule.” Barbara A. Black, “Community and Law in Seventeenth-Century Massachusetts,” Yale Law Journal, xc (1980), 245–246.

18 The Massachusetts Judicial Records Committee has been aided by the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. See Robert J. Brink, “Boston’s Great Anthropological Documents”; Hiller B. Zobel, “The Pompeii of Paper”; and Robert S. Bloom, “Judicial Records—The Foundation of a Statewide Records Preservation Program”; all in Boston Bar Journal, xxii (Sept. 1978), 6–33. The Plymouth Court Records Project, funded by a number of grants, was carried out in association with the Pilgrim Society. See William E. Nelson’s “Introductory Essay,” Plymouth Court Records 1686–1859 (ed. David T. Konig), i, 3–138.

19 David H. Flaherty, Essays, 29. As Flaherty observes, “[T]he fact remains that few court records have ever been employed in analytical and general studies. Quantifying methods can now be used to great advantage. . . .” Ibid., 32. See also David H. Flaherty, “A Select Guide to the Manuscript Court Records of Colonial New England,” American Journal of Legal History, xi (1967), 107.

20 Perry Miller, The Legal Mind in America (New York, 1962), 17.

21 See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession in America (Norman, Oklahoma, 1965), 2 vols.; Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar (Boston, 1911). Paul Hamlin’s Legal Education in Colonial New York (New York, 1939) did use extensive original sources. See also David H. Flaherty, Essays, 16; Morton J. Horwitz, “The Conservative Tradition in the Writing of American Legal History,” American Journal of Legal History, xvii (1973), 275.

22 See Gerard W. Gawalt, The Promise of Power: The Emergence of the Legal Profession in Massachusetts 1760–1840 (Westport, Conn., 1979); John P. Reid, In a Defiant Stance (London, 1977); Maxwell Bloomfield, American Lawyers in a Changing Society, 1776–1876 (Cambridge, Mass., 1976); Stephen Botein, “Professional History Reconsidered,” American Journal of Legal History, xxi (1977), 60–79; Dennis R. Nolan, Readings in the History of the American Legal Profession (New York, 1980); and Daniel H. Calhoun, Professional Lives in America: Structure and Aspiration 1750–1850 (Cambridge, Mass., 1965). On the great influence of Hurst, see Robert W. Gordon, “J. Willard Hurst and the Common Law Tradition in American Legal Historiography,” Law and Society Review, x (1976), 9–56.

23 George L. Haskins, “Lay Judges: Magistrates and Justices in Early Massachusetts,” below, 39–40.

24 See David T. Konig, Law and Society, xiii.

25 The “practicing” limitation excludes colonists with legal backgrounds who acted as magistrates and legislators, but who probably never took clients in the Bay Colony, including John Winthrop, formerly of Gray’s Inn and Inner Temple, Richard Bellingham, Recorder of Boston, England, and Reverend Nathaniel Ward, formerly of Lincoln’s Inn. In an odd way, it is also hard to overlook that lecherous, alcoholic bon vivant, “proud and indolent” Thomas Morton with his “Maypole at Merry-Mount (Wollaston).” He certainly had a legal background, and claimed to be “a gentleman of Cliffords Inn.” He was also described as “a kind of pettiefogger of Furnefells Inn” by a rather prejudiced Governor Bradford. See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, 72; Samuel Eliot Morison, Builders of the Bay Colony (Boston, 1930), 16–17. Morton’s “practice” seemed to involve selling guns and liquor to the Indians for furs. As Morison observed, some of us have “met more spiritual descendants of Thomas Morton than of John Winthrop.” Ibid., 19.

26 Winthrop was an English justice of the peace at eighteen and held court leet for his father at little more than twenty. Ibid., 53; Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop (Boston, 1958), 15–16. He also was admitted in the Court of Wards and Liveries, as was John Humfry. See G. W. Robinson, John Winthrop as Attorney (Cambridge, Mass., 1930). There is some question whether Winthrop was a member of Gray’s Inn, Inner Temple, or both. Morgan says he was admitted to Gray’s Inn in 1613 and took up bachelor residence in Inner Temple. Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Dilemma, 15, 23. The Dictionary of American National Biography (New York, 1960), x, 408 says that Winthrop was “admitted” at Gray’s Inn 25 October 1613 and at Inner Temple in 1628. That explanation is probably correct. Some lawyers were members of one inn, but “migrated” to another. The name of Winthrop’s uncle, Emmanuel Downing, appears next to Winthrop’s entry in the Inner Temple register in 1628/29. Downing was also an attorney of the Wards, and Winthrop was probably joining his uncle’s chambers. Winthrop’s eldest son, John, joined Inner Temple in 1624/25. I owe this information to the kind help of J. H. Baker. Cf. E. Alfred Jones, American Members of the Inns of Court (London, 1924), 219–220, Wilfrid R. Prest, The Inns of Court Under Elizabeth I and the Early Stuarts, 1500–1640 (London, 1972), 208.

27 Ward practiced and studied law in London for nearly ten years before entering the ministry. Ibid., 221. See Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar, 59; Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings (Boston, 1878), 3.

28 See George L. Haskins, “Lay Judges: Magistrates and Justices in Early Massachusetts,” below, 53. See J. P. Dawson, A History of Lay Judges (Cambridge, Mass., 1960), 3–4.

29 See George L. Haskins, “Codification of the Law in Colonial Massachusetts: A Study in Comparative Law,” Indiana Law Journal, xxx (1954), 1; George L. Haskins, Samuel E. Ewing, 3d “The Spread of Massachusetts Law in the Seventeenth Century,” Pennsylvania Law Review, cvi (1958), 413; George L. Haskins, “Influence of New England Law on the Middle Colonies,” Law and History Review, i (1983), 238; Thorp L. Wolford, “The Laws and Liberties of 1648,” Boston University Law Review, xxviii (1948), 426. As to law reform in England, see Donald Veall, The Popular Movement for Law Reform 1640–1660 (Oxford, 1970), 97–240; G. B. Nourse, “Law Reform Under the Commonwealth and Protectorate,” Law Quarterly Review, lxxv (1959), 512–529; Stuart E. Prall, The Agitation for Law Reform During the Puritan Revolution 1640–1660 (Hague, 1960). The law reform movement in England had an interest in the codification of customary law and in establishing a relatively pluralistic and local basis of justice, but its development and character were quite different from anything in the Bay Colony. It was politically more democratic and more radical in its objectives. See Donald W. Hanson, From Kingdom to Commonwealth: The Development of Civic Consciousness in English Political Thought (Cambridge, Mass., 1970), 300–301, 332–339; Gerard Winstanley, The Law of Freedom in a Platform (London, 1652—reprinted 1941 with Introduction by Robert W. Kenny).

30 John D. Eusden, Puritans, Lawyers and Politics in Early Seventeenth-Century England (New Haven, Conn., 1968), 177.

31 Ibid., 174. In Massachusetts, this conviction included notions of recording judgments for use as precedents. As early as 1639, the General Court enacted that

Whereas many judgments have bene given in our courts, whereof no records are kept of the evidence and reasons whereupon the verdit and judgment did passe, the records whereof being duely entered and kept would bee of good use for president [precedent] to posterity, and a releife to such as shall have just cause to have their causes reheard and reviewed, it is therefore by this Court ordered and decreed that thenceforward every judgment, with all the evidence, bee recorded in a booke, to bee kept to posterity. Records of the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay in New England (Boston, 1853), i, 275 (1639). See Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment, 437. Nevertheless, while what might be called the first statutory compilation to be printed in Massachusetts, Lawes and Libertyes, appeared in 1648, there were no printed reports of Massachusetts cases until 1804. See Laurence M. Friedman, A History of American Law, 282–283. The General Court sent to England for two copies of Cokes Reports in 1647. See below, xxxi, note 7.

32 George L. Haskins, Law and Authority, 125–136.

33 “In their respective religious and civil spheres, the Cambridge Platform and The Law and Liberties represented the culmination of an extraordinarily creative period during which the colonists applied conscious design to received tradition. . . .” Ibid., 136. Nevertheless, “little has been done to interpret the Hebraic laws of early New England within a wider context of religious theory and practice.” Stephen Botein, Early American Law and Society, 2. This includes possible talmudic influences.

34 Daniel J. Boorstin describes Chafee’s Introduction as “brilliant.” The American: The Colonial Experience, 381. See also Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment in Early Massachusetts: 1620–1602 (Boston, 1966), a documentary history limited to the punishment of crime.

35 See Morris Cohen, “Legal Literature in Colonial Massachusetts,” below, 245.

36 In 1649 it became “unlawful for any person to ask a counsellor advice of any magistrate in any case wherein he shall be a plaintiffe,” despite the observation by the magistrates that “we must then provide lawyers to direct men in their causes.” Records of the Governor and Company of Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1853), iii, 168. See also Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment, 434. In the 1660 version of the Massachusetts statutes, this provision was essentially reenforced by adding the words “shall or may be plaintiff.” Massachusetts Colonial Laws (Boston, 1887), 141. To whom would a plaintiff now turn for legal advice? The presence of a practicing bar was acknowledged by a 1663 statute that “No person who is an usuall and common attorney in any inferior court, shall be admitted to sitt as a Deputy in this [General] Court.” Records, iv, 87. In 1673, it was enacted “that it shall be lawful for any person by his lawfull attorney . . . to sue in any of our Courts for any right or interest. . . .” Records, iv, 563. The barratry statute of 1656 also took a backhanded notice of legal practice by prohibiting attorneys from fomenting reckless or vexatious litigations. Ibid., 825 Massachusetts Colonial Laws, 9.

Perhaps the most interesting statute was the order in 1650 that “whereas this Commonwealth is much defective for want of laws for maritime affairs . . . the said laws printed and published in a book called Lex Mercatoria shall be perused and duly considered and such of them as are approved by this court shall be declared and published to be in force in this jurisdiction.” Records, iii, 193. This reference to Gerald Malynes’ great commercial law text, Consuetudo, vel, Lex Mercatoria, follows closely on the General Court’s order to England in 1647 for the importation of two copies each of Coke’s Reports, Coke’s First Institutes (“Coke upon Littleton”), [Rastell’s] “Newe Tearmes of the Lawe,” Coke’s Second Institutes (“Coke upon Magna Carta”), Dalton’s Justice of the Peace, and [Coke’s] “Book of Entryes” “to the end we may have the better light for making and proceeding about laws. . . .” Records, iii, 212. These enactments hardly evidence a lack of interest in law or legal development.

37 See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, i, 77–79; Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar, 69–74; Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment, 528; F. W. Grinnell, “The Bench and Bar in Colony and Province (1630–1776) in Commonwealth History of Massachusetts (New York, 1928), ii, 161–164; Henry E. Clay, “The Development of the Legal Profession in the Bay Colony at the Commonwealth—the First 200 Years,” Massachusetts Law Review (Summer, 1981), 115, 116; Nathan Mathews, “The Results of Prejudice Against Lawyers in Massachusetts in the 17th Century,” Address Before the Bar Association of the City of Boston, 9 December 1926, Boston Bar Journal (1926), 73–94.

38 See F. W. Grinell, “Bench and Bar,” 161–164; Nathan Mathews, Results of Prejudice, 80–87 (revocation of charter), 88–89 (witchcraft). “Thus ended the Puritan Commonwealth—a result virtually, and I think literally, due to the absence of an educated Bar.” Ibid., 87.

39 See above, xxx, note 5 and accompanying text.

40 Barbara Black, below, 71, note 5.

41 As to the retention of Paul Dudley, William Shirley, and Robert Auchmuty in Byfield’s later legal affairs, see ibid., 87, 101, 103. There is every reason to suppose similar use of counsel in earlier cases.

42 See David T. Konig, Law and Society, xi–xiii, 89–116; Zechariah Chafee, Jr., Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxix, xxxvi–xxxvii.

43 Ibid., xxxvi.

44 See Marcus W. Jernegan, “The Province Charter (1689–1715)” in Commonwealth History of Massachusetts (New York, 1928), 11, 1–28.

45 See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, i, 77–79.

46 See Charles R. McKirdy, “Massachusetts Lawyers on the Eve of the Revolution: The State of the Profession,” below, 329–330, 334.

47 Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar, 73.

48 Ibid., 72. See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, 77–83.

49 See Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar, 72–73.

50 See Zechariah Chafee, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxiv–xxvi.

51 Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, 79.

52 See Records and Files of the Quarterly Courts of Essex County (1636–1683) (Salem, 1911–1921), iv, 198 (1669), vii, 416 (1680). See also Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment, 438. Cf. Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, 80–81. One individual, Hudson Leverett, did have a pretty bad record, but Chroust is much too facile in assuming that lack of a “liberal education” and formal legal education necessarily created technically incompetent and dishonest attorneys. Ibid., 76–77, 80. While we who teach in formal law schools might wish to believe this is true, elitist prejudice is another possibility.

53 Zechariah Chafee, Jr., Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxv.

54 Ibid., xxv. Chafee states that “by the year 1671, when these records begin, paid attorneys were a recognized, but hardly reputable, class.” Ibid., xxvi.

55 Ibid., xxvi.

56 Ibid., xxvi.

57 Cf. Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, 73–75; Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar, 68–69.

58 See Stanley N. Katz, “Looking Backward: The Early History of American Law,” University of Chicago Law Review, xxxiii (1966), 867, 870–873; Stephen Botein, “The Legal Profession in Colonial North America,” Lawyers in Early Modern Europe and America, Wilfrid Prest, ed. (New York, 1981), 129–130.

59 Zechariah Chafee, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, xxix, xxviii.

60 Ibid., xxviii–xxxv.

61 For example, the actual state of the seventeenth-century legal system must be central to John M. Murrin’s famous thesis that the eighteenth century saw the “Anglicization” of that system. See page xxxix, below.

62 See David D. Hall, “Understanding the Puritans” in Colonial America: Essays in Politics and Social Development, Stanley N. Katz, ed. (Boston, 1971), 31. “It was Calvin, to be sure, who taught the Puritans their legalism, but the political situation in which they found themselves encouraged the development of this legalism beyond the point where he had stopped.” Ibid., 43. See generally Perry Miller, The New England Mind: From Colony to Province (Cambridge, Mass., 1953) 19–67.

63 See Robert J. Brink, “‘Immortality Brought to Light’: An Overview of Massachusetts Colonial Court Records,” below, 471; William E. Nelson, “Court Records as Sources for Historical Writing,” below, 499; Michael S. Hindus, “A Guide to the Court Records of Early Massachusetts,” below, 519 and Catherine S. Menand, “A ‘magistracy fit and necessary’: A Guide to the Massachusetts Court System,” below, 541.

64 See Barbara Black, “Nathaniel Byfield, 1653–1733,” below, 104.

65 See Douglas L. Jones, below, 153–154, and sources cited. There was also severe inflation. Ibid., 154. See “An Overview of Massachusetts History to 1820” in the companion volume to this book, Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts, The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, lvii (1980), 3–19; James A. Henretta, “Economic Development and Social Structure in Colonial Boston” in Colonial America, Stanley N. Katz ed. (1971), 450–465; Marcus W. Jernegan, “The Province Charter (1689–1715)” in Commonwealth History of Massachusetts, ii, 1–28; and Bernard Bailyn, The New England Merchants in the Seventeenth Century (Cambridge, Mass., 1955), 143–197. The colony was “buffeted by demographic and social changes.” See Adam J. Hirsch, “From Pillory to Penitentiary,” Michigan Law Review, lxxx (1982), 1128.

66 The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, lvii, 5–11.

67 Even the bizarre, traumatic Salem witchcraft trials of 1692–1693 have been blamed in part on the dislocation surrounding the revocation of the First Charter. See David T. Konig, Law and Society, 169–185. The Second Charter arrived in Boston on 14 May 1692. On 2 June 1692 Governor Phips and his council commissioned the infamous special court of “oyer and terminer,” without waiting for the newly authorized legislature to convene, which alone had the necessary powers under the Charter to create courts. Ibid., 170. By 22 September 1692 the last of the terrible executions had occurred. Ironically, witchcraft accusations in Andover were halted by a defamation suit. Ibid., 184.

The causes of the “witchcraft outbreak” remain the focus of a torrent of scholarly work beyond the scope of this conference, but a high rate of social change doubtless contributed to the kind of anxiety that, in the same year, sent sixty armed men from Gloucester into the woods to “intercept a spectral force of French and Indians.” Ibid., 167. It is ridiculous to blame the prosecutions on the lack of “trained lawyers of courage and force to challenge the legality of the special court,” cf. Anton-Hermann Chroust, i, 77, and equally unavailing to blame the trials on the colonial legal system. The witch proceedings were terminated by Governor Phips in May 1693 never to occur again. The King’s Privy Council refused to approve the General Court’s effort in the 1692–1693 session to place witchcraft back on the list of capital crimes. The recantation of Judge Samuel Sewall, read for him by the Reverend Samuel Willard during a service at the Old South Church on 14 January 1697, a day of fasting and prayer designated in memory of “the late tragedie,” marked the end of an era. Judge Sewall stood silently in the church as the recantation was read. It is sobering to recall that the “Second Charter” period, with its legal and professional growth, began with such a symbol. See Edwin Powers, Crime and Punishment, 455–5095 John Demos, “Underlying Themes in the Witchcraft of Seventeenth-Century New England,” Colonial America, Stanley N. Katz ed. (1971), 113–133; Demos, Entertaining Satan: Witchcraft and the Culture of Early New England (New York, 1982); Paul Boyer, Steven Nissenbaum, Salem Possessed: The Social Origins of Witchcraft (Cambridge, Mass., 1974). As to the considerable extent of colonial witchcraft persecutions at other times and places, see E. W. Taylor “The Witchcraft Episode (1692–1694),” Commonwealth History, ii, 29–62.

68 John M. Murrin, “The Legal Transformation: The Bench and Bar of Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts” in Colonial America, Stanley N. Katz ed., 415 (Katz’s summary).

69 Ibid., 416.

70 Ibid., 421–425.

71 Ibid., 448.

72 See ibid., 4485 Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans, 195–205.

73 See the sources cited in note 2, xxv, above, and the articles of David H. Flaherty and Charles R. McKirdy, below. In the “companion” volume to this book, Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts 1620–1820, The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, lvii (Boston, 1980), the editors set out criteria for establishing true “professionalism” among doctors, such as “how doctors in eighteenth-century New England identified themselves,” how they “differentiated themselves from other healers,” their development of professional education, what doctor-patient relations were “expected,” and “what colonial doctors exploited from their own past.” Ibid., 32. It is obvious that comparative study of these two professional developments, legal and medical, would be most fruitful, and it is hoped that the publication of these two “companion” volumes will encourage such study.

74 There were approximately 1,500 blacks, slave and free, in Boston in 1750. See Sherwin L. Cook, “Boston: The Eighteenth Century Town,” Commonwealth History, ii, 229. There was also racism. In 1723 the Boston Town Meeting voted to recommend to the General Court an act for the restraint of “Indians, Negroes and Mulattoes” that prohibited, among other things, their possession of firearms, visits from slaves, street gatherings, and loitering. They would be required to bind out their children at four years of age to a white master. Ibid., 227–228. Slaves were sold in Boston in 1746. Ibid., 228. There is an obvious contrast here to the Puritan statute of 1647 limiting bond slavery. See Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession, i, 52.

75 Douglas L. Jones, below, 190. James A. Henretta has observed that, in 1687, “the distribution of political power and influence in Boston conformed to . . . a wider, more inclusive hierarchy of status, one which purported to include the entire social order within the bonds of its authority. But the lines of force which had emerged on the eve of the American Revolution . . . now failed to encompass a significant portion of the population. . . . Society had become more stratified and unequal. Influential groups, increasingly different from the small property owners who constituted the center portion of the community, had arisen at either end of the spectrum.” Colonial America, Stanley N. Katz ed., 462–463.

76 David H. Flaherty, below, 193.

77 Ibid., 240.

78 Ibid., 241.

79 Neal W. Allen, Jr., below, 275.

80 Ibid., 287.

81 Ibid., 309.

82 Ibid., 312.

83 Morris L. Cohen, below, 253.

84 Ibid., 253–254.

85 Ibid., 256–261.

86 Ibid., 256.

87 This argument certainly was not missed by John Adams. See Daniel R. Coquillette, below, 412–416.

88 See Diary and Autobiography of John Adams ed. L. H. Butterfield (Cambridge, Mass., 1961), i, 210–211, in, 275–276. For an old man’s recollection of the famous day of his youth, see John Adams’ letter to William Tudor, 29 March 1817, in John Adams, Works, Charles Francis Adams ed. (Boston, 1817), x, 244–245.

89 See Charles R. McKirdy, below, 337–358. (Appendices III and IV.)

90 See David Flaherty’s review of William Nelson’s Americanization of the Common Law in the University of Toronto Law Journal (1976), 116. James Henretta has argued that the Revolution was “in reality the completion of a long process of social evolution, simply speeded up and given a positive articulation by the war. . . . Except for the disruptions caused by the war itself and the Loyalist emigration . . . most of the changes . . . represented the culmination of previous trends.” James A. Henretta, The Evolution of American Society, 1700–1815, An Interdisciplinary Analysis (Lexington, 1973), 169. See also Flaherty, “Review,” 116–117; Stanley Katz, “Looking Backward: The Early History of American Law,” Chicago Law Review, xxxiii (1966), 884.

91 John P. Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted: John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials,” American Journal of Legal History, xviii (1974), 189, 191.

92 Ibid., 191. See also Erwin C. Surrency, “The Lawyer and the Revolution,” American Journal of Legal History, viii (1964), 125.

93 George Dargo, Law in the New Republic (New York, 1983), 7.

94 “[The changes] affected some legal institutions and not others, and some areas of American Law more than others.” Ibid., 7. Dargo has argued that the Revolution had a “deep, abiding, and immediate impact on American public law,” ibid., 8 (emphasis supplied), but that in terms of private law the changes were much more gradual—although eventually very important. “What is striking, in fact, is the strong continuity of private law in the revolutionary era.” Ibid., 8. This view is quite compatible with that of Morton J. Horwitz, set out below, lii.

95 See Daniel R. Coquillette, below, 376–382, 395–400; Charles R. McKirdy, below, 339–358, [Appendix IV].

96 Ibid., 318–323. See also Daniel R. Coquillette, below, 395–400.

97 See John D. Cushing, “The Judiciary and Public Opinion in Revolutionary Massachusetts,” in Law and Authority in Colonial America, George A. Billias ed. (Barre, Mass., 1965), 173–182, 185, n.19.

98 Ibid., 182. These efforts included careful charges to the grand juries which explained “the social compact and its violation by Great Britain.” Ibid., 174.

99 See George Dargo, Law in the New Republic, 48–59, for an excellent description of the “sudden increase of lawyers” and the new “private” law schools.

100 See John M. Murrin, “The Legal Transformation: The Bench and Bar of Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts,” 446–448.

101 John P. Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted,” 191.

102 “Both sides were dedicated to following the forms of law but both were prepared to manipulate those forms for their own advantage. It was the forms of law and the idea of legality that mattered, for they kept the situation from escalation into violence; manipulation was a matter of strategy not of abuse.” Ibid., 194.

103 See Reid’s analysis of John Adams’ personal view of the Tea Party. “Adams was a lawyer, a conservative lawyer, and it is significant that . . . he found, as did so many other whigs, that constitutional legality was at times determined by political necessity.” John P. Reid, In a Defiant Stance, 99. The political pressure on the entire Massachusetts legal system by the years 1769–1771 was so great that Hiller B. Zobel has concluded “[I]n cases involving political subjects, the Massachusetts judicial system . . . was under such powerful pressure from both sides that a fair trial was, without extra legal assistance, unlikely, if not impossible.” Hiller B. Zobel, “Law Under Pressure: Boston 1769–1771” in Law and Authority in Colonial America, George A. Bellias ed. (1965), 204. See also Michael S. Hindus, Prison and Plantation: Crime, Justice, and Authority in Massachusetts and South Carolina, 1767–1878 (Chapel Hill, 1980), 33–36.

104 Ibid., 65, 67.

105 “What had appeared to be utopian plans for a large prosperous, well-trained legal profession before the war became a reality in the postwar period.” Gerard W. Gawalt, The Promise of Power, 36.

106 George Dargo, Law in the New Republic, 48.

107 Ibid., 59. The extremely high growth rates in the legal profession recall the very rapid expansion of the Inns of Court in the period 1500–1600, when the annual rate of admission quadrupled. The growth rate continued to be high until the Civil War. See Wilfrid R. Prest, The Inns of Court, 1–70. Morton Horwitz, in a different context, suggests that we should be alert to recapitulation of English experience, but no major comparative studies of the rate of growth of the legal profession and the causes and consequences have ever been undertaken. Cf. Morton Horwitz, Transformation of American Law, 1780–1860 (Cambridge, Mass., 1977), 17.

108 See Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Colonial Experience, 195–205.

109 Charles R. McKirdy, 328.

110 In particular, McKirdy draws on W. E. Moore’s The Professions: Roles and Rules (New York, 1970) and B. Bledstein’s The Culture of Professionalism (New York, 1978) to isolate and describe five characteristics that measure “professionalism:” 1) full-time earning occupation, 2) need for useful, theoretical knowledge and requirement of formal education, 3) group “identity” by members, 4) “service” orientation, and 5) autonomy from outside control. These factors compare closely with those set out by the editors of our companion volume, Medicine In Colonial Massachusetts, 1620–1820, The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, Publications, lvii, 32.

111 John Adams was an elitist, but one who looked to academic performance and formal professional requirements to block the nepotistic careers of the sons of the leading tory families, as well as to eliminate “pettifoggers.” See Daniel R. Coquillette, below, 395–400. Among McKirdy’s most interesting Appendices is his “Appendix II—Professional Choices of Harvard Graduates: 1642–1760.” Before 1684, and the “Intercharter Period,” there was but one “law” career choice. During the 1685–1691 “Intercharter Period,” there were four. But during the 1692–1760 “Second Charter Period,” there were seventy-six Harvard graduates who ultimately would call themselves “lawyers,” with twenty-seven alone in the ten-year period 1751–1760. While this was still well behind the clergy (the most popular choice) and medicine (nearly twice as popular as law), it was a most impressive indicator as to the growing prestige of the profession and its expectations for education. See Charles R. McKirdy, below, 333–336 (Appendix II).

112 See John P. Reid, “A Lawyer Acquitted,” 191–194; and Daniel J. Boorstin, The Americans: The Colonial Experience, 191–205. As Reid observed: “[I]n the functioning of eighteenth century constitutional legality, local institutions defined the meaning of ‘law’ as much as did imperial institutions.” John P. Reid, In a Defiant Stance, 72.

113 See Janice Potter and Robert M. Calhoon, “The Character and Coherence of the Loyalist Press” in The Press and the American Revolution, Bernard Bailyn, John B. Hench eds. (Boston, 1981), 231. On the peculiar influence of classical studies on the American colonial mind, including minds as distinct as John Winthrop and John Adams, see Richard M. Gummere, The American Colonial Mind and the Classical Tradition (Cambridge, Mass., 1963). See also Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), 23–24; Stephen Botein “Cicero as Role Model for Early American Lawyers: A Case Study in Classical Influence,” Classical Journal, lxxiii (1977–1978), 314–318; Charles F. Mullett, “Classical Influences on the American Revolution,” Classical Journal, xxxv (1939–1940), 93–94.

114 See Perry Miller, The Legal Mind in America (New York, 1962), 20–21, 31–32, 41–43; Felix Gilbert “Intellectual History: Its Aims and Methods,” Historical Studies Today, eds. Felix Gilbert, Stephen R. Graubard (New York, 1972), 141–158; Patrick Gardiner, The Nature of Historical Explanation (London, 1952), 115–139. See also William E. Nelson’s original essay “The Eighteenth-Century Background of John Marshall’s Constitutional Jurisprudence,” Michigan Law Review, xxvi (1978), 893, 900–901, 917–924.

115 See Daniel R. Coquillette, “Legal Ideology and Incorporation I: The English Civilian Writers, 1523–1607,” Boston University Law Review, lxi (1981), 1–2, 3–10; “Legal Ideology and Incorporation II: Sir Thomas Ridley, Charles Molloy, and the Literary Battle for the Law Merchant, 1607–1676,” Boston University Law Review, lxi (1981), 317–320, 371.

116 Of course, in focusing on ideology, one must not forget the historical context. Thus, even as John Adams struggled for good civil law precedents in the case of the Liberty, Sewall v. Hancock, 1768–1769, “[a]n ensuing riot drove the customs commissioners to Castle William in Boston Harbor, where they remained until the troops which they had urgently requested were garrisoned in Boston.” See L. Kinvin Wroth, “The Massachusetts Vice-Admiralty Court” in Law and Authority in Colonial America, George A. Billias ed., 53.

117 See John M. Murrin, “The Legal Transformation: The Bench and Bar of Eighteenth-Century Massachusetts,” 446–448.

118 Morton J. Horwitz, Transformation of American Law, 4–9.

119 “And while Americans always insisted on the right to receive only those common law principles which accorded with colonial conditions, most of the basic departures were accomplished not by judicial decision but by local statute. . . .” Ibid., 5. Massachusetts statutory policy during the Second Charter period remains a great area for future research. See above, xlv.

120 According to Horwitz, “ . . . American judges before the nineteenth century rarely analyzed common law rules functionally or purposively, and they almost never self-consciously employed the common law as a creative instrument for directing men’s energies toward social change.” Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1.