Criminal Practice in Provincial Massachusetts

DURING the twentieth century Americans have been fascinated by the careers of prominent criminal lawyers.751 One might easily presume that lawyers specializing in criminal law have always dominated criminal trials. Yet, at least in one early American jurisdiction, lawyers only gradually became involved in criminal practice and then only to a limited extent compared to their role in the civil courts. This essay began as an effort to discover what could be learned about the practice of criminal law in Massachusetts. The results are both disappointing and revealing. Although a surprising amount of information exists about the practice of criminal law, a great deal remains elusive, especially because of the limitations of the available evidence.

It is now reasonably well established that the first half of the eighteenth century witnessed the first flowering of the Massachusetts legal profession.752 Yet a great deal remains unknown about the nature of legal practice and the actual role of counsel during the provincial era. One cannot simply assume that attorneys did for their clients what their successors do today, especially in criminal as opposed to civil practice. Nor can one simply look to eighteenth-century England for relevant models, since lawyers played almost no role in English criminal trials for felonies until well into the second half of the eighteenth century.753 Nevertheless, the existence of voluminous court records for Massachusetts does make it possible to shed some light on the nature of criminal practice during the provincial era.

Beginning in 1692 the Superior Court of Judicature, the Court of Assizes and General Gaol Delivery, exercised jurisdiction over the most serious crimes tried in Massachusetts courts. It was overwhelmingly a court that handled civil disputes, which, as will be seen, may have influenced criminal practice. It is likely that the emerging role of defense counsel was largely a spillover from practices and roles accepted in civil litigation. The Assizes or criminal side was largely a court of first instance for serious crimes, meeting at least once a year in and for each county in the colony. It also heard appeals from county courts of General Sessions of the Peace. There were 1,461 criminal prosecutions before the Assizes between 1693 and 1769, 1,192 based on original jurisdiction (81.6 percent), and 269 appeals (18.4 percent).754 Whether an appeal was based on a matter of law or fact was largely irrelevant, because the appellant in fact received a new trial in almost every case before new judges and a new jury. Although the amount of serious crime tried before the court was comparably modest because of an effective system of social control at work in society, most sittings of the Assizes, especially in the largest counties, heard at least one criminal case.755

Criminal prosecutions at the Assizes, as revealed by the extensive records of cases tried before the court between 1692 and 1770, provide several interesting perspectives on colonial legal practice. The first section of this essay will identify those attorneys who most prominently appeared in the records as defense counsel. The second section suggests general ways in which the presence of lawyers was to the advantage of defendants. It also explores general evidence which indicates an increased presence, as well as an improved proficiency, of defense counsel. There is also evidence which helps to explain the interplay between civil and criminal practice.

The final section shows how scattered cases can be pieced together to illustrate the activities of attorneys at particular stages in criminal proceedings. As will be seen, lawyers during the provincial period represented clients at bail and plea bargaining proceedings; they attempted to quash indictments; they argued the facts and legal merits of cases at first instance and on appeal; they were even sometimes involved in sentencing and pardons. From the first to the last stages of the legal process, the beginnings of the so-called “professionalization” of the American criminal trial are evident in the early eighteenth century.

The Leading Criminal Lawyers

The use of lawyers at the Assizes depended in large part on the development of the legal profession through the gradual appearance of trained lawyers in the province. Those accustomed to reading about the surplus of lawyers today must adjust to the small numbers of the provincial era. Gerard Gawalt concludes that there were fifteen practicing lawyers in 1740, twenty-five who attained the newly created rank of barrister in 1762, and seventy-one in 1775.756 The paucity of highly trained professional attorneys during the first generation of the Superior Court’s existence (1692–1710) may have contributed to the infrequent appearances of lawyers at criminal trials. This characterization must be made with caution. Although research for this essay has uncovered evidence that was previously unknown, concrete conclusions about the presence of attorneys and their role in criminal cases for this early period must be reserved, because of the character of the surviving records. After the creation of the Superior Court, a small number of lawyers were seemingly present at each session, and they were definitely employed in at least a few criminal cases on behalf of defendants. A major enactment in 1701 pertaining to “attorneys” repeated the common Massachusetts stipulation that any plaintiff or defendant in any civil suit could represent himself or employ the assistance of any other person.757 It provided for the formal admission of attorneys to practice before particular courts upon the administration of an oath which made the lawyer an officer of the court with a responsible role to play in the administration of justice.758 The records of the Superior Court occasionally refer to the admission of attorneys in subsequent years. The statute of 1701 limited a party to one sworn attorney in a civil case; this limit was raised to two in 1708.759 The subsequent increase suggests what other evidence indicates, that more lawyers were available by the end of the first decade of the eighteenth century. Yet the 1701 enactment clearly presumes that civil cases would be the main business of attorneys.

A handful of lawyers appear to have been the leading practitioners in criminal cases at the Assizes in the first half of the eighteenth century. Since they have been elusive figures in the pages of history, this essay will first introduce the leaders among them: Thomas Newton, John Valentine, John Read, Robert Auchmuty, and John Overing.

The legal profession that was beginning to emerge in the 1710’s and 1720’s could furnish clients with specialized assistance in criminal prosecutions. At least eleven new attorneys were admitted to practice by the Superior Court during these decades.760 Thomas Newton (1660–1721) and John Valentine (1653–1724) stand out as the two leaders of the Massachusetts bar during the first two decades of the eighteenth century. Newton was one of the most active lawyers before the Superior Court in the early eighteenth century, especially in criminal cases. He was born in England in 1660. As a newcomer to Boston, he took the oath as an attorney before Samuel Sewall in 1688. The latter subsequently served as a justice of the Superior Court from 1692 to 1728. Newton, who presumably had received some legal education in England, became a justice of the peace in 1715. He served as a deputy-judge of the Admiralty Court in Massachusetts and was elected Attorney General in July 1720 and served to his death on 28 May 1721. In 1707 he began a royal appointment as comptroller of the customs in Boston, which he also held until his death.761 The newspaper report of his death described him as for “many Years one of the chief Lawyers of this Place. A Gentleman very much belov’d who carried himself handsomely and well in every Post, of a Circumspect and inoffensive Walk and Conversation, of strict Devotion towards God and Humanity to his Fellow Creatures, a Lover of all Good Men, much Lamented by all that knew him.”762

John Valentine was the other notably prominent lawyer during the early decades of the eighteenth century. The son of a Lancashire merchant, he probably immigrated to Boston with his father in the early 1670’s. A “well-trained lawyer,” he served both as Attorney General (1718–1720) and Advocate General. At times during his distinguished career, he combined his considerable talents with those of Thomas Newton, defending persons accused of illegal trade and also prosecuting pirates.763 On 1 February 1724 John Valentine committed suicide. A coroner’s inquest of eighteen persons viewed the body as it hung in his own house. Justice Sewall noted that “Some Justices and many Attorneys were present. The jury returned that he was Non Compos”764 The bearers at his public funeral were John Read, Robert Auchmuty, John Overing, John Nelson, and Robert Robinson. Valentine died a wealthy man with a total estate worth more than four thousand pounds. His books alone were worth more than one hundred pounds, and he also owned three slaves.

The passing of Newton and Valentine left two relative newcomers, John Read and Robert Auchmuty, as the leaders of the Massachusetts bar in the 1720’s and 1730’s. Read had an extraordinary career. Born in Connecticut in 1680 and graduated from Harvard in the class of 1697, he served until 1707 as a Congregational minister in various Connecticut towns. His conversion to the Church of England led to his resignation in 1707 from the Stratford pulpit. Sometime between 1708 and 1711; Read settled in New Milford, Connecticut, where, as Clifford K. Shipton describes it, “possessing much spare time, a keen mind, and pressing legal disputes over land, he naturally turned to the law.”765 He became self-trained in the law. In a letter to President John Leverett of Harvard seeking legal advice about disputes over some of his own land in June 1708, Read described himself as an abdicated clergyman, who had “fallen out with the times.” Although he claimed that he knew “little in the Law never making it my Study but sometimes a little for diversion,” the tenor of the letter and his analysis of his own legal problems suggest that he was learning quickly.766 In the fall of 1708 he became the sixth attorney admitted to practice in Connecticut under a system of admission begun the preceding May. During the next several years his career did not prosper. He even found himself cited for contempt of court before the Court of Assistants and temporarily suspended from practice.

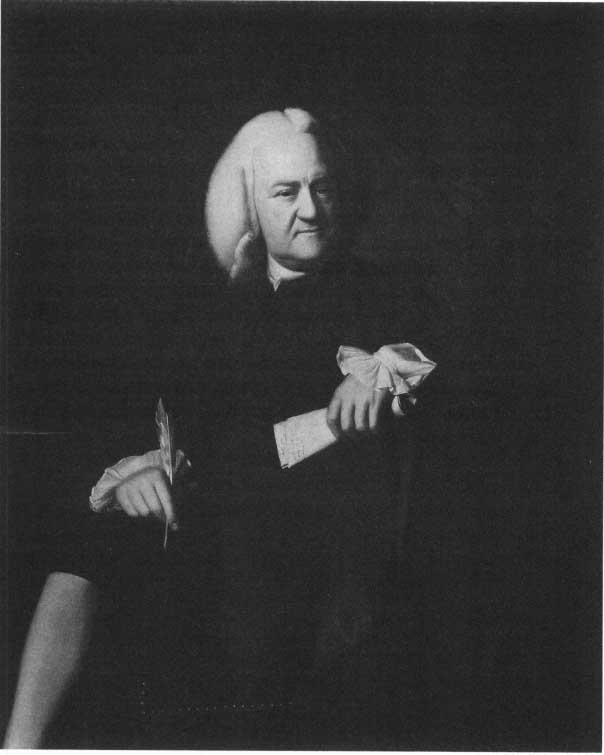

15. Paul Dudley (1675–1751) by an unknown artist (circa 1720) Chief Justice, Superior Court of Judicature; Attorney General. Courtesy, Supreme Judicial Court.

Read’s legal career finally began to flourish. In December 1719 he evidently travelled to Salem, Massachusetts, to represent Governor Gurdon Saltonstall of Connecticut. In December 1718 the latter had written a letter of introduction for Read to President Leverett, explaining that Read would appear for him “upon Mr. [Paul] Dudleys Remove, and being unavoidably hindred from attending there my Self.” Saltonstall asked Leverett to lend his “old Law Book” to Read and to direct him to a 1695 statute on intestacy.767 In 1720 he travelled to Boston as one of the commissioners from the New England colonies to discuss currency problems. This experience may have convinced Read to move to the metropolis of Boston in 1721 at the age of forty-one. From 1723 to 1728 he served as the elected Attorney General of the province, which made him the chief prosecutor at the Assizes. His activities during this decade began to distinguish him as the outstanding New England lawyer of his generation. Chief Justice Sewall recognized his abilities on 28 August 1727 when he gave Read “a General Retaining Fee to plead any Cause I might have.” In the late 1720’s the General Court retained him to defend a sheriff sued for false arrest in a criminal case.768

Robert Auchmuty, who also came to Massachusetts from a different jurisdiction, is another example of an English-trained lawyer who made successful use of his advantages in the New World. He was born in Scotland, admitted to the Middle Temple in 1705, and called to the bar in England in 1711. The last point suggests that he had taken his legal education seriously and actually managed to learn some law at the Inns of Court, which were primarily dining and social clubs.769 Nothing further is known about the beginnings of Auchmuty’s legal career in England. However, given the fact that criminal defense work hardly existed there, a lawyer from the mother country brought no specialized knowledge of the practice of criminal law to the colonies, except perhaps for handling misdemeanors.

Auchmuty must have made the acquaintance of Samuel Shute, because he seems to have accompanied the new governor to Boston in the fall of 1716. On 22 October 1716 Sewall reported that “the new Lawyer” Auchmuty and John Valentine pleaded at the proving of an individual’s will. Sewall seems to have initially been suspicious of the newcomer. On 20 December 1716 he made clear his dislike of Auchmuty’s bantering about matrimony with a minister at a dinner they attended together. Four days later he, perhaps enviously, recorded seeing the lawyer with Governor Shute. But by the spring of 1717 Sewall had begun to admire Auchmuty’s legal abilities. He attended a hearing between Cambridge and Charlestown about the location of the county seat: “Mr. Auchmooty pleaded very well for Charlestown: His first Discourse was very well worth Hearing.”770

Auchmuty’s entrance into the practicing bar was successful. Judging from the surviving records of arguments prepared for their clients, he and Read were the most popular and sophisticated criminal lawyers in the province during the 1720’s. John Read’s continued service as Attorney General during the middle of this decade left the role of defense counsel to Auchmuty on a great many occasions.

Surprisingly little is known about Auchmuty’s private and personal life through the 1720’s and thereafter. The matter is of some interest because he was a defendant before the General Sessions in Boston in 1722 in a peculiar prosecution. He and a woman were indicted for living together for four months as husband and wife although unmarried. When first presented in January, his several pleas on his own behalf to quash the indictment were overruled. He then pleaded not guilty and the case was continued until the April sessions, when Auchmuty withdrew the former pleas and stated that he was now married. He defended his previous behavior by claiming that he and the woman had been married privately at an earlier date, but not in conformity with Massachusetts law. The couple were fined five pounds each and costs.771

Another leading practitioner in terms of frequency of appearances and positions held was John Overing (1694–1748) who was born in England, and brought to Boston that same year. He began to practice law in Boston about 1720 and did so until his death on 29 November 1748. Overing may have studied law with Auchmuty; his marriage to the eldest Auchmuty daughter suggests a close association with the family.772 During almost all of the 1730’s and 1740’s, Overing enjoyed gubernatorial appointments as Attorney General, which made him the chief criminal prosecutor in the province. He continued to engage in civil practice during these years, especially since his official position brought him to public notice and furnished increased opportunities for clients.

By the 1730’s and 1740’s the normal process of legal education in Massachusetts involved attendance at Harvard College and practical apprenticeship in the office of an established lawyer or judge. John Murrin has noted that “the Harvard and Yale classes of 1730 through 1738 contributed seventeen lawyers to Massachusetts. The next nine classes, caught up by the Great Awakening, added only nine.”773 He argues that the leading lawyers of the 1730’s were still Englishmen and outsiders in Massachusetts, although it seems difficult to apply such terms to attorneys like John Read, Robert Auchmuty, and William Bollan, who had been residents in the province for some time. Murrin suggests that most Massachusetts recruits to the new profession of law came from undistinguished families and, like Read, had had a negative response to a career in the church.774

The increased incidence of talented young Massachusetts men professionally associating themselves with the bar instead of the Bible suggests that the attractions outweighed any of the disadvantages sometimes associated with the legal profession. During this generation there were relatively few published attacks on lawyers. The newspapers reported an attorney who absconded from his creditors, another convicted of forgery, and one attacked while a candidate at election time, but two of these three episodes occurred in England.775 A Boston newspaper even printed an adulatory poem about “the Portion of a Just Lawyer.”776 Knowledgeable persons nevertheless associated certain traits with members of the bar, such as those described in a private letter from Jonathan Sewall of Charlestown to Thomas Robie in Marblehead on 15 April 1757: “for I cannot conceive it possible for you to triumph over such a strict Inquisition, without the help of Equivocation, Evasion, Unintelligible Jargon, Impudence, etc. in short, without being compleat Master of the Art of disguising Truth.” Robie had allegedly displayed such characteristics in warding off attempts to discover the identity of Lindamira, a pen name used by Sewall and himself in some correspondence.777

The leaders of the Massachusetts bar during the 1730’s and 1740’s were Auchmuty, William Bollan, Overing, Read, and William Shirley.778 Auchmuty maintained his reputation as the leading criminal lawyer of his generation in terms of recorded appearances at the Assizes and was probably the leading lawyer in the province as well, since John Read had reached a venerable age. Auchmuty was also a prominent man of affairs in Massachusetts, which was not unusual for a leading member of the bar. For example, the province selected him to assist in the New Hampshire-Massachusetts boundary dispute in the 1730’s. He was also a judge of the Massachusetts Vice-Admiralty Court from September 1733 to 1747.

Auchmuty was a friend of Governor Jonathan Belcher until the pair had a falling out in the fall of 1739. In the mid-1730’s Belcher in a letter to his son in England had referred to Auchmuty and William Shirley as “two of the most eminent of the long robe here.”779 Belcher’s compliments changed to contempt in a letter to a prominent friend in New Hampshire in September 1739, which reported that the naval officer in New Hampshire had “made a valuable seizure, and a good one, worth 4 or 5000£. The Irish Judge [Auchmuty] is a villain, and the Advocate [William Shirley] a greater, so it may be lost without good advice and assistance. The Judge and Advocate will clear the ship and cargo, if they can, but I think in this case it’s hardly possible.”780 It took less than two months for the impossible to happen in Vice-Admiralty Court. By November the Governor wrote concerning Auchmuty that “I don’t thank him, nor forgive him, nor can I ever again allow myself any acquaintance with so uncommon a rascal.” He believed Judge Auchmuty hardly ever made a decision in favor of the king, because he was bribed to the contrary: “I suppose there’s not a more finisht villain than the former in Christendom.” Belcher was, of course, primarily concerned about losing his own share in the Admiralty proceedings, and by November 1740 he was even denouncing Auchmuty in letters to his son in England, whose education on Auchmuty’s character had now come full circle.781

Auchmuty’s friend and ally in the Admiralty Court, Shirley, became governor in 1741 and sent him to London in the early 1740’s to conduct an appeal in the Rhode Island boundary case. On 4 May 1742 Shirley informed the Duke of Newcastle of Auchmuty’s presence in England as a colonial agent and of the governor’s awareness that Auchmuty was scheming to have the secretary of the province replaced.782 Auchmuty spent most of the years 1742, 1743, and 1744 in England.783

John Read remained the elder patriarch of the New England bar through the 1730’s and 1740’s, even though his presence in criminal matters at the Assizes is less evident than that of Auchmuty, who was younger than Read but who had begun to practice in Boston about five years earlier. The editors of the Legal Papers of John Adams have called Read the “leading Massachusetts lawyer of the first half of the eighteenth century.”784 Other lawyers such as James Otis, Sr., and the much younger John Adams had the highest opinion of Read. Thomas Hutchinson called him “a very eminent lawyer and, which is more, a person of great integrity and firmness of mind.”785 Read was kept busy as a senior legal advisor to the province in Admiralty proceedings and in the boundary commissions with Rhode Island and New Hampshire.786 He also enjoyed the distinction of being the first lawyer from Boston elected to the House of Representatives in 1738 and to the Council in 1741 and 1742. In January 1739 and July 1741 his colleagues appointed him to committees to prepare substantially new editions of statutes.787 Read also continued to represent persons at the General Sessions in Boston.788 He was one of the bail bondsmen for two accused persons in 1740, suggesting the multiple roles of provincial lawyers, especially when it came to supplementing their incomes.789 As late in his life as 1749, he served as acting Attorney General at the Assizes in Suffolk, Bristol, and Essex counties.790 He also was involved in a considerable amount of civil business at Inferior Courts of Common Pleas and the Superior Court of Judicature. When Read died in Boston on 7 February 1749, he owned more than fifty volumes of legal works, about half of which were law reports.791

The Use of Defense Counsel

Evidence derived from the assize records of 1693 to 1709 indicates that fewer than a half dozen attorneys were practicing criminal law in Massachusetts. There is a problem evaluating the extent of legal representation, since court files rarely specify that attorneys have appeared on behalf of defendants. The most common evidence is found in cases appealed to the Assizes, since attorneys normally signed their names to reasons of appeal. In some unusual prosecutions in 1708–1709 for illegal trade with the enemy the records reveal that defendants asked the court for permission to be represented by Valentine and Newton; it is not clear whether such petitions were normally necessary, and the wording of the records suggests that the requests were pro forma.792 In a few other cases before 1710 the bill of costs submitted to the province included a twelve shilling fee for an attorney, thereby indicating the presence of a defense lawyer.793

Massachusetts defendants enjoyed the right to employ counsel in any type of criminal case, which was a marked departure from the English rule of allowing counsel as a matter of right only in misdemeanor cases, but not for felonies, which covered most serious and many not-so-serious crimes.794 Blackstone stated that it was a settled rule that no prisoner could have a lawyer in a felony trial, “unless some point of law shall arise proper to be debated.” The theory was that the judge served as counsel on matters of fact for the prisoner charged with a felony, whose innocence would emerge spontaneously during the trial without the assistance of a hired “mouthpiece.” Since this practice was so much at odds with the existing right to counsel in trials for misdemeanors, Blackstone wrote in the middle of the eighteenth century that it was the custom of judges “to allow a prisoner counsel to stand by him at the bar, and instruct him what questions to ask, or even to ask questions for him, with respect to matters of fact: for as to matters of law, arising on the trial, they are intitled to the assistance of counsel.”795 Yet the use of defense lawyers in England remained exceptional; the privilege of counsel in all cases of felony did not exist until 1836.796 Massachusetts did not use the English distinction between felony and misdemeanor in either theory or practice. Most of the approximately 1,200 original prosecutions between 1693 and 1769 were for what can usefully be described as serious crimes, even if the term felony would not be appropriate, in part because the province had less than a dozen capital offenses and sentenced an average of less than one person a year to death. The appellate jurisdiction of the Assizes, which averaged less than 20 percent of the total number of prosecutions, comprised a variety of charges that often approximated misdemeanors.

Massachusetts moved closer than the English during the first half of the eighteenth century to the modern form of lawyer-dominated criminal trial, since normally the prosecution and sometimes the defense were represented by lawyers. This encouraged the pursuit of justice at least to the extent that experienced lawyers were regularly available at the Assizes, thereby promoting such standards as fairness in decisions and regularity in procedure. Lawyers in the province could meddle at will with questions of law and fact during trials. The growing presence of lawyers in the Massachusetts courtroom thus put at least some limits on the influence of the bench at the General Sessions and the Assizes. James Cockburn has pointed out that the English judiciary opposed the increased use of counsel in the late eighteenth century, at least in part because they challenged the “constant and pervasive influence of judicial interference” in criminal trials.797 Massachusetts judges had to accept the role of lawyers in their courtrooms as a fact of life 3 both English and Massachusetts judges had to live with the juries that made the ultimate decisions about guilt in most cases.

Contemporary recognition of the gradual development of the legal profession in provincial Massachusetts is illustrated by the lofty conception of lawyers set forth by the distinguished Puritan minister, Cotton Mather. His Bonifacius. An Essay upon the Good, published in 1710, somewhat surprisingly included several pages of positive advice for lawyers. One of Mather’s first prescriptions is that they be skillful and learned in the law through extensive study and reading.798 A lawyer should be a scholar and be wise in order to do good:

A lawyer must shun all those indirect ways of making haste to be rich, in which a man cannot be innocent: . . . Sir, be prevailed withal, to keep constantly a court of chancery in your own breast; and scorn and fear to do anything, but what your conscience will pronounce, consistent with, yea, conducting to, glory to God in the highest, on earth peace, good will towards men. . . .

This piety must operate very particularly, in the pleading of causes. You will abhor, Sir, to appear in a dirty cause. If you discern, that your client has an unjust cause, you will faithfully advise him of it. . . . You will be sincerely desirous, Truth and Right may take place. You will speak nothing that shall be to the prejudice of either. You will abominate the use of all unfair arts, to confound evidences, to browbeat testimonies, to suppress what may give light in the case.799

The surprising element in Mather’s characterization of lawyers and their obligations is the positive tone he adopts 3 the anti-lawyer sentiments alleged to have been so common in the previous century seem to have dissipated, even though Mather seems well aware of the less attractive possibilities of legal practice.800 At the opening of the new courthouse in Boston in 1713, Justice Samuel Sewall of the Superior Court further characterized the appropriate role for lawyers: “Let this large, transparent, costly Glass serve to oblige the Attornys always to set Things in a True Light, And let the Character of none of them be Impar sibi [unequal to himself]; Let them Remember they are to advise the Court, as well as plead for their clients.”801

17. Samuel Sewall (1652–1730) by John Smibert (1729). Chief Justice, Superior Court of Judicature; Judge of the Probate Court, Suffolk. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

At the very least these statements by Mather and Sewall acknowledge the presence of attorneys. Before discussing the actual roles of lawyers at various stages of criminal proceedings, including appeals, several general observations are germane. First, the evidence suggests that the special skills of attorneys helped defendants. For instance, at the Middlesex Assizes in July 1723 the crown brought a perjury prosecution against two gentlemen, Joseph Buckminster and Thomas Smith. When the grand jury returned a true bill, Attorney General Read added this note to the indictment: “Joseph Buckminster being sick made a Motion by his Attorny John Valentine Esq. that the said Valentine might be allowd to plead against the indictment.” The judges then permitted Valentine and Read to debate the pleas in open court before quashing the indictment “for the Insufficiency thereof.”802

A petition presented to the Superior Court for Hampshire County in September 1721 revealed a belief in the utility of an attorney for a person accused of a serious crime, which probably reflected commonly-held views. Ovid Rushbrook, a convicted counterfeiter, who was facing another prosecution in Springfield, reminded the justices that he had freely given evidence for the crown and was pleading guilty, “tho’ he is advis’d by some to deny it and they will Ingage him a Lawyer in Court that shall stand By him there, But such advice your petitioner minds not.”803 The 1723 trial of Daniel Tuttle of Wallingford, Connecticut, for uttering a counterfeit bill in Boston, specifically illustrated the actual benefits of legal assistance. The jury returned a special verdict on the issue of what constituted an uttering under provincial law: “Upon which Special Verdict the Kings Attorney General as well as the said Daniel Tuttle by his Council were fully heard and after Mature Advisement thereon” the court found Tuttle not guilty.804 Most accused would have found it impossible to match wits with Attorney General Read on such an issue.

A second general observation is that lawyers’ skills seem to become more sophisticated throughout the first half of the eighteenth century. There are many indications that attorneys became more legally adroit. For example, in the spring of 1723 Joseph Woodsum of Berwick appealed a conviction in a paternity prosecution to the York Assizes. His attorney argued that contrary to established practice the mother did not accuse Woodsum during childbirth and that therefore her oath was not adequate to convict him. The bench at the Assizes reheard both parties and affirmed the lower court sentence.805 The result was different in an identical appeal to the Plymouth Assizes in April 1728, in which a woman’s oath had been enough to convict the appellant at General Sessions. This time Robert Auchmuty had prepared the reasons of appeal in an expansive and sophisticated form. He stated that the mother had not followed the proper accusatory procedures established by provincial law. An accusation by a single person had to be done during childbirth: “This being a penall Statute and altering the Common Law as to the Mode of Evidence must by the Rules of Law be Expounded Litterally and strictly and therefore no other Mode of proof will be Sufficient or Equal to the Manner of proof required by the Law in these cases.”806 A modern expert has pointed out that in England “the eighteenth century witnessed the growth of a presumption in favour of a strict construction of criminal statutes which persists to this day.”807 Overall, Auchmuty presented one of the most persuasive series of reasons of appeal extant for the 1720’s. The Assizes accepted the argument of counsel and reversed the decision of the lower court, despite testimony that the appellant had threatened to murder the mother, if she accused him during childbirth.808

It seems most likely that the evolving practices of lawyers in civil suits influenced this increased sophistication in criminal practice. Such a process reflected the fact that the legal profession gradually emerged in the early eighteenth century in response to the commercialization and maturation of society. Thus Boston remained the headquarters for the leading lawyers attracted there during the provincial era. All practicing lawyers had far greater opportunities to earn income from civil actions, which were much more voluminous than criminal prosecutions at the Superior Court of Judicature. In the provincial era civil business always comprised the vast bulk of a lawyer’s work.809 The small annual number of criminal prosecutions, coupled with regulated fees, made the Assizes no source for a criminal lawyer to earn a decent living. The extremely low rate of recidivism also meant that there was no regular, returning clientele for the most part. It seems likely, however, that a reputation in criminal work helped to attract the necessary volume of civil business at all superior and inferior courts. The low fees and the low rates of recidivism also were bound to encourage the use of defense counsel by defendants, who were almost always personally inexperienced as objects of criminal prosecutions.

The participation of lawyers in civil suits is also easier to document. The records of civil cases display lawyers’ attempts at introducing various innovations, which probably led to comparable efforts in criminal practice. A major study of criminal procedure in colonial New York noted “a tendency, perceptible also in England, for rules used in civil litigation to be applied in criminal cases where the pressure of analogy made the precedents persuasive, and where counsel was on hand to use the advantage.”810 At Suffolk Superior Court in 1715, for example, the crown, in a civil case, appealed an adverse decision about money due to the crown. After losing again, Thomas Newton moved an appeal to the King and Council in England on behalf of the crown: “The Court are of Oppinion that no Appeal lyes in this Case.”811 A comparable attempt at innovation occurred at Salem on 16 December 1718, when John Read from Connecticut appeared on behalf of the Saltonstall interests. “After long Pleadings on both sides; Mr. John Read offered a Demurrer in a sheet written which the Court look’d upon as an Innovation, and inconvenient to be introduced, Especially because the Defendant refus’d to join in the Demurrer, being just now offer’d; and not seen before. And therefore ’twas unanimously Rejected.”812 Since only two of the five members of the court at the time had had formal legal training, the bench may have been generally suspicious of the “new tricks” of lawyers. The presence of trained lawyers in court contributed to the growing professionalization of the Superior Court itself during the first half of the eighteenth century.

Legal assistance was also helpful to a defendant if civil litigation for damages paralleled a criminal case. Pleas in civil cases were, by the nature of the problems that arose in litigation, more sophisticated than in criminal prosecutions. Read and Auchmuty were among the ablest pleaders during the 1720’s. Read demonstrated his abilities at the Charlestown Superior Court in January 1729, when he was first successful in quashing for insufficiency the presentment of ten men for riotously assembling with axes and clubs and cutting down some fence belonging to David Gold of Stoneham. Read then represented one of the same defendants, Timothy Sprague, in an appeal from a decision of Middlesex Common Pleas the previous month. Gold had successfully sued Sprague for damages to his crops after the destruction of the fence.813

Firm evidence about the activities of lawyers before trials at the Assizes appears in written reasons of appeal filed by attorneys on behalf of appellants from criminal convictions, which again had no real English equivalents. In Massachusetts the sense of justice was very tolerant of appeals in criminal cases, normally from courts of general sessions to the Superior Court of Judicature, but the burden of additional court costs on appellants kept the number of such appeals from becoming excessive. An analysis of these reasons of appeal sheds additional light on the general nature of criminal practice, particularly the benefits counsel offered clients, and exhibits improved legal competency. Reasons of appeal were rarely sophisticated legal efforts: they mainly deny the facts charged and question the adequacy of the evidence for conviction. For example, when stating the reasons of appeal for a Boston baker, Lately Gee, appealing a conviction for altering a bond, Robert Auchmuty first asserted that his client should have been found not guilty. Secondly, he argued, “that the proofs in the Case are not Sufficient in the Law to Support the said Indictment and to Convict the Appellant.” The third point was more novel: “by the very proofs in the Case it Evidently appears nothing Criminaliter [creating criminal liability] in the Law wuld or ought to have Charged or fastened on the Appellant.” At the trial Auchmuty must have elaborated on these simple points in a persuasive manner, since the jury acquitted his client.814

The reasons of appeal asserted by Christopher Jacob Lawton for his client, Matthew Copley, Jr., a Suffield “bloomer” accused of assaulting a deputy sheriff of Hampshire County in 1729, claimed that the “Facts Charged in the Complaint on which the Appellant received his Tryal as aforesaid was not proved by any such Evidenc as the Law should or Can Own.”815 Lawton sent these reasons to the clerk of the Superior Court in Hampshire, appending a note: “If you see anything amiss in the above please to alter and you will highly oblidge your servant.” Such a rare request suggests the attorney, in fact, lacked formal legal training. Attorney General John Overing wasted little time in denying the force of these reasons of appeal, charging that the evidence was sufficient to convict, “and as it satisfyed the former Jury we have great reason to pray confirmation and costs.” At the Assizes the jury proved Overing was a good prophet by finding Copley guilty.816

Still, the preparation of reasons of appeal benefited from the advice of counsel, who contributed to the development of the law by proposing more and varied rationales for quashing or reversal. The list of reasons furnished the bench and/or the jury with plausible alternatives, especially in cases where the weight of popular sentiment lay with appellants. An appeal by three yeomen from Falmouth in Barnstable County to the Assizes in 1726 illustrates this process at work. The trio were convicted at Edgartown in Dukes County for riotously seizing Thomas Tupper. John Otis, Jr., the attorney who prepared and filed the reasons of appeal, first asserted that the jury should not have found his clients guilty, “there being no evidence of the facts set forth in the Inditement only the complainant who was not bound by Recognizance to prosecute your Appellants.” Secondly, he pointed out that Tupper did not have a house but only a small hut on the island in dispute and had himself indeed evicted the appellants, who at the time Tupper erected his cottage “had been Quietly and Peaceably in Possession of Island of Nonamosett [Nonamesset] for more than Three Years as Tenants to John Winthrop Esq. of New London.” Thirdly, “the Appellants further say said Judgment was wrong by reason The Inditement was Joint and Your Appellants Jointly tryed and the Judgment is Severally viz; each to pay a fine of Four Pounds.” The judges seized on a fourth reason of appeal to reverse the conviction. Otis pointed out that his clients were convicted at a general session held by adjournment on the last Tuesday of October, but that this was illegal since the law required a new session to begin on that day.817 Laymen could not have produced such a varied list on their own.

Persons who used legal assistance on appeal had probably employed the same lawyers at the General Sessions. Robert Sturgeon, a Watertown gentleman, illustrated the possibilities by employing both Robert Auchmuty and Robert Robinson to represent him at the General Sessions in Middlesex County, where he was tried for contempt of the General Court for continuing to preach in a local church although forbidden to do so. At the Middlesex General Sessions his attorneys made several pleas to quash the indictment, which Attorney General Overing successfully opposed. The bench also overruled the claim that Sturgeon had a right to preach but permitted him, with the approval of the Attorney General, to have the full benefit of the plea at the next assizes. Auchmuty prepared the reasons of appeal, including several references to English cases. At the Superior Court of Judicature, Sturgeon’s lawyers succeeded in obtaining a special verdict from the jury, but the bench found against him after advising on the verdict for approximately six months.818

It is a measure of John Read’s special talents that his reasons of appeal in criminal cases were the most elaborate and sophisticated of any of those still extant from the 1720’s.819 His defenses more frequently moved beyond simple denial of guilt or of certain facts into substantive or procedural issues. In 1729 two New Hampshire laborers were charged with leading a group of Irishmen in an assault on some “English people” in a dispute over land ownership. At the Essex General Sessions Read first argued that the Massachusetts court had no jurisdiction since the alleged assault and battery took place in New Hampshire. Secondly, he argued that the presentment should be quashed for the duplicity of its contents, since it did not charge both defendants with the same offenses. Read next asserted that the defendants had acted lawfully by virtue of a warrant from a justice of the peace. When it came time to file reasons of appeal, Read essentially repeated these same oral arguments. The text of the reasons ran to a full page, which was much lengthier than most such papers. But the effort was wasted. For some unknown reason Read’s clients failed to appear in court to prosecute their appeal, which was not uncommon. After the judgment against the pair was affirmed, they were taxed the substantial amount of £38.10.6 in court costs.820

Overall, the use of defense counsel was well established by the 1720’s at the latest, although the problems of proving this statistically are immense because of the unreliability of the surviving evidence. Efforts to produce statistical tables about the presence of attorneys are doomed to failure for such reasons. The hard evidence concerning the presence of attorneys is as follows. There is direct proof of the presence of defense counsel in 5 (4.5 percent) of 110 cases in the period 1700–1710, 34 (18.9 percent) of 181 cases in the 1720’s, and 26 (12.9 percent) of 202 cases in the 1740’s. Lawyers appeared in all counties and in cases from appeals of minor convictions to trials of capital offences. The crucial point is that this is the minimum proof available; there is every expectation that much more defense work occurred, especially by the 1720’s. The evidence above is based only on those decades for which a search for every file paper in a particular case was made, since it is most often the file papers, especially reasons of appeal, that indicate the presence of defense lawyers. But there are very few file papers for any cases in the first decade of the eighteenth century. There are no file papers available, for example, for seven of a total of twenty-four prosecutions for theft during the 1720’s. It is rare for the formal entries of the trial to refer to attorneys, except when the record specifies that the prisoner was heard by his counsel on a point, but sometimes the clerk of court’s entry states the prisoner’s defense was heard without specifying whether or not the accused presented his own case or had representation. In certain grouped prosecutions against the same persons at the assizes, a defense lawyer participated in the appeal, but there is no evidence of his likely participation in defense of the original prosecutions as well. The overall numbers listed above also include cases that are counted in the overall totals, but in which there was no role for defense counsel, such as a situation in which the grand jury returned an ignoramus and no trial ensued, or a prosecution against an individual for failure to appear to prosecute an appeal to the assizes. Finally, there are cases in which pleas for benefit of clergy or to challenge indictments, for example, are recorded in the court records without any definite proof that, as seems likely, an attorney Entered such pleas for the defendant.

The Role of Defense Counsel at the Assizes

Lawyers were unlikely to be employed to assist defendants in preliminary examinations before justices of the peace and were not permitted to be present when the Attorney General or a local prosecutor was privately setting forth the grounds for proceeding with a prosecution before a grand jury at either the general sessions or the assizes.

An episode in 1723 at a court of general sessions raised the issue of the specific stage in a prosecution when an individual could employ counsel. Daniel Clark refused to respond to a presentment for selling liquor without a license unless he was permitted a lawyer. The Essex county bench told Clark he could have counsel after he pleaded. When Clark continued to demand legal advice at once, the general sessions dropped the presentment and proceeded to convict him on an earlier plea before a justice of the peace.821

One of the few instances before the actual start of a trial when a lawyer could formally help a client was in preparing a petition for bail or appearing at a hearing on petition for bail. A major episode that indirectly sheds light on this point occurred in December 1705, after two carters, Thomas Trowbridge and John Winchester, Jr., refused to give way to a carriage carrying Governor Joseph Dudley. The pair were committed to prison at the insistence of the Governor. His son Paul, the Attorney General of the province and a lawyer trained in England, opposed the granting of bail. It took almost a week for the justices of the Superior Court of Judicature to allow it. The important point for our purposes is that the two prisoners had no attorneys at the hearing, nor, according to Justice Sewall, could they procure any in this politically sensitive case. Not surprisingly, the few lawyers in Boston who practiced criminal law were unwilling to take a stand against the Governor and the Attorney General. At least Sewall’s account implies that one could be represented by counsel in a hearing for bail.822

Records of bail hearings remain rare in subsequent years, in part because it was uncommon for defendants to be held in jail pending a trial. On at least two occasions Robert Auchmuty brought petitions for bail to the assizes on behalf of his clients. John Taggart was in Cambridge jail for assaulting Robert Butterfield during the sitting of the Suffolk Assizes in August 1739. He applied for a writ of habeas corpus to be moved to the Boston jail, so that he “might be admitted to give Bail, and to be proceeded with as to Law and Justice appertains.” Auchmuty apparently prepared a separate petition for bail for Taggart, which the court granted. He reported that Butterfield had now recovered from his wounds, and since his client’s trial was not scheduled until January 1740, he would have to spend a long time in jail during the winter. The system of bail did not work well initially in this episode, because both Patrick Taggart, a co-assailant who was not jailed, and John Taggart required much prompting, including the issuance of writs of scire facias, before finally appearing in court for their trials. This caused problems for Auchmuty, who was evidently operating a private system of bail bonding and had stood surety for the pair.823 Auchmuty also acted for David Doughty of York County in February 1747 when he prepared a petition to the Suffolk Assizes for a writ of habeas corpus. Doughty was in jail on suspicion of murder, but his attorney claimed that the inquest had showed the victim did not die from a murderous act and that prison was hurting his client’s health.824

These two isolated episodes in 1739 and 1747 are unlikely to represent a new trend in criminal practice. Incomplete record-keeping seems a better explanation for the absence of materials showing the role of lawyers in bail hearings. Moreover, the speediness with which trials occurred in the provincial era, especially for serious crimes tried at the Assizes, meant that the accused rarely spent much time in jail awaiting trial. Finally, bail was in fact granted fairly easily, except for persons charged with capital offenses.

A person indicted by a grand jury came before the Assizes for trial by jury, unless he or she pleaded guilty. Arraignment involved entering a plea after a reading of the indictment, and at this point a lawyer could really begin to help his client.

It was probably only after being indicted that most individuals acquired counsel. There is evidence of the court’s appointing counsel, as in 1702–1703, when the Superior Court assigned John Newton as the attorney for Adam, a Negro, during a dispute in civil and criminal courts with the prominent John Saffin over Adam’s freedom.825 Also, a suspect at Hampshire General Sessions on 20 January 1736, who moved for counsel when he was required to plead to an indictment for fornication, had an attorney assigned to him.826

At the Worcester Assizes in September 1768 the court appointed John Adams to defend Samuel Quinn, who was accused of rape. Adams’ own record suggests that Quinn had asked for him to be appointed.827 After Quinn’s acquittal, he was remanded to jail on another indictment for assault with intent to ravish. Adams continues the story: “When he had returned to Prison, he broke out of his own Accord—God bless Mr. Adams. God bless his Soul I am not to be hanged, and I dont care what else they do to me.” Writing in his diary in June 1770, Adams recalled his pleasure then: “Here was his Blessing and his Transport which gave me more Pleasure, when I first heard the Relation and when I have recollected it since, than any fee would have done. This was a worthless fellow, but nihil humanum, alienum. His joy, which I had in some sense been instrumental in procuring, and his Blessings and good Wishes, occasioned very agreable Emotions in the Heart.”828 Adams’ client subsequently pleaded guilty and was severely punished with whippings and a twelve-month imprisonment.

At least in theory, and sometimes in practice, a lawyer could engage in plea bargaining, attempt to quash an indictment, advise his client about pleading guilty or not guilty, and assist his client during trial by jury. The overwhelming majority of suspects in original prosecutions pleaded not guilty. Even some of those who initially admitted their guilt at a preliminary examination pleaded not guilty upon subsequent arraignment and were ultimately acquitted. When Daniel Tuttle of Wallingford, Connecticut, was in jail in Boston in the early 1720’s charged with the much-feared crime of counterfeiting, he fully confessed his crime and was promised that he could furnish evidence for the crown. Yet Tuttle then pleaded not guilty and was acquitted by the justices after a special verdict.829 The important difference for Tuttle was that he had a lawyer at his trial, who may well have encouraged his plea of not guilty and helped to persuade the jury to return a special verdict. The judges of the assizes permitted this lawyer to argue before them on the special verdict.

The evidence for plea bargaining in general and for the role of lawyers therein is indirect and elusive.830 There was one specific episode in Boston in February 1749 where persons charged with burglary pleaded guilty to theft only after the Attorney General declared that he would not prosecute them for burglary.831 It is possible that the Attorney General had simply reconsidered the strength of his case or, perhaps, personal factors may have played a decisive part in the plea bargaining decision. It is interesting that Robert Auchmuty was the acting Attorney General. As a leading criminal lawyer who never served full time in that prosecutorial post, he may have been personally amenable to such an accommodating arrangement. This episode, brought out in open court, evidently received the approbation of the judges. Although this episode is the only concrete evidence found on plea bargaining, the suspicion remains that the practice was more common than the formal records indicate, especially when multiple charges of counterfeiting against the same individual or prosecutions for burglary (a capital offense) were actually tried as simple thefts. If attorneys wished to plea bargain for their clients, the professional climate in Massachusetts was favorable. The leading lawyers travelled and lived together on circuit with the Superior Court and knew each other intimately. The Attorney General was someone who might return shortly to a defense practice. An Attorney General pro hac vice may have been even easier to deal with because of the temporary nature of his elevation to represent the crown at one specific sitting.

Pleas by lawyers to quash indictments are the most commonly-documented episodes involving counsel in the surviving records of the assizes that I have examined. In an early case in November 1708 involving illegal trade, John Borland, a prominent Boston merchant, and William Rouse, a Charlestown sea captain, both used attorneys, with the court’s permission, to try to quash indictments. Thomas Newton and John Valentine initially pleaded that the court did not have jurisdiction over the offense, an argument which the court rejected. They then argued that Borland was an accessory rather than a principal and further that “there is no Month, day or year Mentioned when the Goods were Sold.” After the court overruled all of the motions to quash, Borland pleaded not guilty and a jury acquitted him. Captain Rouse had better luck in attempts to quash his indictment for illegal trade. His lawyers were overruled in questioning the jurisdiction of the court, but succeeded on the grounds that there was no mention of the county where he lived.832 The nature of the arguments advanced clearly illustrates the important role of defense counsel in a controversial and highly visible case.

By the 1720’s attorneys were making several types of special pleas to quash indictments. These were a seeming novelty in the 1720’s, and another reflection of the development of the legal profession since 1710. Reasons of appeal often included a plea to quash an indictment that had served as the basis for prosecution at the general sessions. A person who failed to quash an indictment below could reserve such a plea for consideration at the assizes. Since reasons of appeal tended to include every possible ground for winning a case, the typical arguments did not distinguish between attempts to quash an indictment and efforts to defeat the prosecution on a legal issue or on a factual basis. As was evident in an earlier discussion, lawyers adopted a multiple approach to drafting reasons of appeal, hoping that one of their points would strike home. Such a pattern also characterized reasons of appeal in civil cases, which may have inspired the use of written reasons in criminal cases as well.833 The prosecution of Daniel Clark, a Topsfield innholder, for swearing and for striking one Jesse Dorman, illustrates the use of reserved pleas. In the fall of 1723 an Essex county grand jury indicted Clark at the General Sessions. The defendant employed John Overing, who had completed a one-year term as Attorney General in June, to prepare his pleas. He pointed out the failure to include the time and place of the alleged offense, the abode of the defendant, and the name of the county: “The presentment ought to be Quashed for that 2 Crimes of Different Nature are Joined in same presentment.” The General Sessions ignored these assertions of error and convicted Clark but permitted an appeal. The Essex Assizes in May 1724 swiftly quashed the presentment on the basis of the reserved pleas.834

The uncertainty of a presentment was a major reason to reverse a conviction on appeal.835 It is a reminder that, unlike England, Massachusetts lacked a corps of trained persons to serve as justices of the peace and court clerks, especially at the sittings of the general sessions, and on-the-job training in the province occasionally was of questionable quality.

It appears, however, that the assizes were not always hospitable to procedural pleas and that the judges preferred to try a case on its merits whenever possible. They were probably resistant to seeming quibbles raised by lawyers. The proof underlying this observation is that most original prosecutions and appeals went to trial. After 1724 the judges could refer to legislative authority. In late November the General Court decided it was devoting too much time to fashioning relief for parties and criminal defendants that had lost appeals “through some error or mistake in the party, or his attorney, and sometimes of the clerk of the court, in misreciting the parties or judgement, or misnaming the courts appeal’d to or from, or otherwise.” The legislation directed the Superior Court judges to “order an amendment of such defective or mistaken reasons of appeal, and to proceed to tryal of the cause, as though no such error had been committed.”836

A case involving a group of appellants from Dedham, who were convicted of interrupting a town meeting, demonstrates a reluctance of the high court justices to accept technical pleas to quash indictments. The second reason of appeal filed by attorney Robert Robinson argued that the indictment should have been quashed because provincial law had appointed another mode of redress in the event that the defendants had indeed disturbed the meeting. They could only have been fined five shillings if the facts alleged were true.837 In answering these reasons of appeal in preparation for the Suffolk Assizes in August 1728, the newly-elected Attorney General Joseph Hiller, perhaps overzealous in the first few days of his brief term in office, not only denied the force of Robinson’s argument but offered him an elementary legal lesson. He argued that the indictment was good, “but if not the appellant Council should have pleaded to quash it at the Court below, and he would have served his Clyents better than he will be able to do now by putting the reason for quashing it into their Reasons of Appeal.” The justices apparently agreed with the Attorney General, since they permitted the appellants to be tried by a jury, which convicted them.838

There were at least two cases on appeal before the Assizes during the 1720’s in which errors in the indictments and presentments prepared at the General Sessions led to a quashing of the prosecution. No indictment drafted at the Assizes, however, was found insufficient, which suggests that the Attorney General either did these himself or supervised the work of clerks more carefully because of the seriousness of the charges.839 One appeal involved a husband and wife convicted at Northampton in March 1721 of fornication before marriage. The attorney for the couple, who is not named, filed substantial reasons of appeal that nevertheless missed the essential technicality on which the prosecution foundered at the assizes. The original indictment simply said: “We the Grand jury do Present Eben Dickenson and Sarah Dickenson his wife of Hadley for the sinn of fornication.” The justices reversed the sentence “for that the presentment of the Grand Jury does not alledge the Fornication to be Committed before Marriage and no time laid in the presentment when the Fact was committed.”840 Such prosecutions were common at the general sessions, but they were rarely appealed, which suggests that recourse to defense counsel was worthwhile when individuals felt particularly aroused or aggrieved by a charge or conviction. An accused at the general sessions had limited incentive to spend money on a lawyer until conviction, since an appeal to the assizes was a matter of right and led to another trial before new judges and a new jury. The risk of incurring high costs of court at the assizes created a countervailing pressure.

The issue of errors in presentments and indictments was again a factor at the Suffolk Assizes in November 1723 in an appeal of a conviction for selling strong drink without a license. At general sessions the indictment asserted that Henry Whitton of Boston had sold strong drink without a license “within three months last past.” Most persons accused of this common crime simply paid their fines; Whitton was obviously aroused enough to take on the financial burden of hiring a lawyer to represent him at the general sessions and later on appeal. In September 1723 Robert Robinson tried to quash this presentment at the general sessions: “The Defendant pleads that the Presentment doth not set forth any certain Day when he sold the Drink mentioned in the presentment without Licence wherefore it is uncertain for the Defendant to know how to make Answer thereto and ought therefore to be quashed for want of Certainty.” After the general sessions overruled this plea and a jury found Whitton guilty, Robinson repeated his earlier plea in written reasons of appeal to the Assizes. In responding to these arguments, the Attorney General argued that the fact of Whitton’s selling drink without a license was plainly proved “by one witness to three severall facts at severall times for selling drink without License which being soo notorious the Jury made noe hesitation but found the Appellant guilty of the same.” The assize judges followed Robinson and quashed the indictment “for the uncertainty thereof, there being no day therein laid when the Drink was Sold.”841

Since pleas to quash indictments were not recorded in the formal court records, there are problems exploring the degree of legal sophistication of such pleadings. It seems likely that the types of objections raised in the material just treated were comparable to those recorded in reasons of appeal discussed earlier. It is clear that the bench quashed indictments in a relatively few instances, such as at the Suffolk Assizes in February 1743 when the court quashed two or three indictments against Mary Barry for counterfeiting, “upon the pleas made by her Attorney Benjamin Kent for Quashing the same.”842

Once an accused person had pleaded not guilty and the trial had actually begun, the role of defense counsel was one of argumentation, mostly over facts, but sometimes over the law. The latter point must be made with a great deal of caution, since there are no trial transcripts in the modern sense for provincial Massachusetts. The only “law report” for colonial Massachusetts comprises notes taken in court by Josiah Quincy, Jr., between 1761 and 1772. Although he reported only four criminal cases, defense lawyers definitely appeared in three of them. Quincy noted that the trial at the Suffolk Assizes of Jemima Mangent for infanticide lasted from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., “during which Time neither Judges or Jury departed. It turned chiefly on Matters of Fact.” Despite this focus, the defense cited a long list of legal authorities, including English statutes, treatises, and law reports.843

Although legal authorities were cited during trials, as the Mangent case demonstrates, an analysis of this issue requires two prefatory points. First, most trials seem to have involved disputes over facts rather than laws. Thorny issues of substantive or procedural law were less likely to emerge in criminal cases than in civil litigation, especially in the first half of the eighteenth century, when lawyers were only beginning to make their presence felt. Statutes defining the elements of criminal behavior in the province were simple and straightforward. The central issue was whether the accused had committed the act charged in the indictment. Secondly, the absence of transcripts for trials limits awareness of the extent of recourse to legal authority by defendants and their attorneys. Knowledge of this issue depends heavily on the written reasons filed by appellants. In the early eighteenth century these documents tended to be very factual in nature, as the appellants primarily sought to rebut the Crown’s version of the facts in a case.844 Occasionally, attorneys made semi-legal points as part of the reasons of appeal.845 But there was little evident legal sophistication either in the argumentation or in the issues at stake in trials. Most matters in dispute had a factual basis, which either had to be established or undermined in what was essentially a new trial at the Assizes.

The wording of indictments indicates that the primary task of the Assizes was to enforce the province’s criminal statutes.846 The recorded instances of references to such laws at actual trials, at least during the 1720’s, occurred in reasons of appeal. At Bristol in 1721 Robert Auchmuty, the attorney for three Freetown assessors appealing a conviction for neglect of duty, referred to a specific statute requiring towns to support ministers. This task was the burden of the selectmen, who alone should be bothered when problems arose. Auchmuty perhaps unwisely added that “the Wisdome of no Court is above the Law.” In an additional reason of appeal Auchmuty discussed another statutory provision: “If it should be pretended that the said Judgment or Sentence is grounded upon the Province Law page 175 there likewise the Appellants Conceive the said Judgment or Sentence is wrong and Erronious for that Enables the Court of quarter sessions in case of a Delinquencie of selectmen or Assessors to appoint three or more sufficient freeholders within the County to assess or apportion the same etc all which the said judgment has not allowed neither were there any grounds or reasons for such a proceeding.” Auchmuty’s reasoning was in vain, since the full bench affirmed the judgment below against the assessors.847

Judges and lawyers used English statutes when they proved relevant, especially if there was no comparable provision in provincial law. In one of the few explicit references to English statutes found in the records of the assizes, John Read in the 1720’s cited laws concerning. misbehavior on the Sabbath enacted under Edward III and Queen Mary in 1376 and 1553 respectively.848 Read also cited a case from 12 Coke’s Reports. The records of the Suffolk Assizes for 1725 contain an undated summary of the laws of England concerning the escape of prisoners.849 During this period the assizes presided over the prosecution of Lieutenant John Lane, a gentleman from York, on a charge of escaping from the Boston jail.850 This summary was perhaps prepared for the use of the judges or submitted to them by attorneys involved in the case.

Citation of English cases from printed reports, which constituted the true backbone of the common law, was more restricted than reference to English statutes. Although English decisions could be cited in Massachusetts courts, colonial judges and lawyers probably had limited access to such material. The unsophisticated nature of legal argumentation in criminal cases in the first half of the eighteenth century may have been due in part to a general paucity of treatises and law reports to which reference could be made. An English authority noted that in the seventeenth century “Coke’s Third Institute was the principal authority as to the criminal law, and the little which he says on the subject is fragmentary and incomplete.”851 Sewall owned this treatise, first published in 1644, which he referred to as Coke’s Pleas of the Crown. He read passages in open court and at hearings on several occasions.852 Sir Matthew Hale’s brief and methodical summary of the Pleas of the Crown appeared posthumously in 1678 as a manual for circuit riders, and his major two-volume History of the Pleas of the Crown, written in 1676, did not appear in print until 1736. Hale’s two books became, in succession, the leading English authorities on the criminal law. Since several judges attending the Charlestown Assizes in 1705 discussed one of Hale’s religious tracts of 1677 over dinner, it seems possible that they knew his Pleas of the Crown as well. The contents of the 1736 volumes seem particularly sophisticated in comparison to the kinds of legal arguments that were recorded in Massachusetts courtrooms.853

The basic handbook for justices of the peace commonly used in the American colonies was Michael Dalton’s Countrey Justice (1618), which went through numerous seventeenth- and eighteenth-century editions. At the Ipswich Assizes in 1702 the crown’s answer to reasons of appeal cited Dalton on a particular point.854 At a 1705 meeting of the provincial council both Sewall and Governor Dudley cited Dalton in discussing how to handle a petition from George Lawson, whose home had been attacked by a mob because of an adulterous affair.855

Knowledge is lacking about English legal materials held in public and private hands in provincial Massachusetts. Only random information is currently available. Anthony Stoddard, for example, was a justice of the peace in Boston after 1715 and a judge of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas for Suffolk County after 1733. When he died in 1748, he owned Hawkins’ Pleas of the Crown, justice of the peace handbooks by Dalton and Nelson, and Lilly’s Abridgement of English Law.856 There is no reason to think that such holdings were unusual for a lower-court judge. Sewall built his own library, and it stands to reason that other Superior Court justices did so as well. In Boston in 1686 a person left three books for Sewall: “one is Michael Dalton, the second is Gilberts Presidents, the third is the office of clerk of Assise, and Clerk of the Peace. . . .”857 It seems especially significant for the subsequent history of the Massachusetts Assizes that Sewall owned or at least had read the 1676 or 1682 editions of the standard handbook for operating such a court.858 After Thomas Newton died in 1721, his library was advertised for sale as “the greatest and best collection of law books that ever was exposed to sale in the country.”859 John Read had more than fifty volumes of English treatises and law reports when he died in 1749. The Harvard College library had fifty-seven law books in 1723, about 2 percent of its total holdings.860

Newspaper advertisements during the 1740’s offered for sale such items as Coke’s Institutes and Reports, law dictionaries, and guides for justices of the peace. The only volumes of English law reports listed by name are Lord Coke’s.861 The estates of such varying personages as Lieutenant Governor Spencer Phips, who was a justice of the peace for Middlesex County, and Daniel How, a yeoman in Shrewsbury, revealed ownership of statute books, guides for justices of the peace, and legal dictionaries. Nahum Ward, a justice of the peace who died in Shrewsbury in 1754, divided his law books between two sons. Artemas Ward, Harvard College, class of 1748, became a justice of the peace himself in 1750 at the age of twenty-three.862 When John Adams was studying law in Worcester in the mid-1750’s, he read Hawkins’ Pleas of the Crown. Benjamin Prat (1711–1763), who began to practice with great success in Boston about 1745, used to bring lawbooks to court to argue various points.863 This was probably typical.

The general attitude of the Superior Court toward English legal opinions seems evident in 1712 when Justice Sewall himself sought English legal advice on a case pending before the assizes. In a letter to the Massachusetts agent Jeremiah Dummer on 22 April 1712 Sewall enclosed a memorandum on a case, “upon which I intreat you humbly to ask the Advice of my Lord Chief Justice Parker, or Sir Peter King; or of whom you shall think most convenient; and send the resolution by the first opportunity.”864 Parker was Lord Chief Justice of the Queen’s Bench and King was Recorder of London. The case involved Hittee, an Indian girl, found guilty of arson by a jury. At her sentencing it was suggested that she was under sixteen years of age. Sewall wondered whether the issue of her age could be determinative at this stage of the proceedings, since the age had not been included in the jury’s verdict. Dummer did obtain advice for Sewall, but its nature is unclear.865 The practical solution was to try Hittee again for the same offense at the Plymouth Assizes in March 1713. This time the indictment specifically stated that she was a full sixteen years of age in June 1711 when the alleged offense occurred. A jury then acquitted her.866 The probability that she had already been in a prison for almost two years must have strongly inclined the jury to have mercy on this Indian girl.

Concrete evidence of the citation of specific English treatises and reported cases at the Assizes is infrequent. On occasion there was a vague general reference to a practice that was against the common law. A reason of appeal from a fornication prosecution in Hampshire County is unusual in that it stated the law of England concerning legitimate births and referred the court to Sir Edward Coke’s First Institutes (London, 1628) for substantiation.867 Robert Auchmuty cited specific English cases on behalf of several defendants in the 1720’s. In July 1723 at an appeal at Cambridge by Robert Sturgeon, a gentleman from Watertown, of a conviction for continuing to preach although forbidden to do so by the authorities, Auchmuty argued in one of his reasons of appeal that “the verdict is uncertain and ambiguous and by many Cases in the Law no Judgment can be made thereupon.” Another lawyer might simply have made this assertion, but Auchmuty added specific page references to law reports and treatises.868

One of the most outstanding recorded displays of legal argumentation in the provincial period occurred at the Suffolk Assizes in the fall of 1724, when Attorney General John Read relinquished his prosecutor’s role and defended John Checkley on a charge of criminal libel, an exceptional offense with political overtones. The notes used by Read in defense of his client appear in detail in his own hand in the records of the Assizes.869 Although full records of this sort are extremely unusual, Read’s arguments demonstrate that the leading attorneys had the ability to rise to the occasion in major prosecutions. He quoted at least ten English cases in the course of presentation of arguments for reversal of his client’s conviction. Most of the citations are from Salkeld’s King Bench Reports and Shower’s Kings Bench Reports. But Read did not simply use the cases as window-dressing. He discussed each situation and distinguished it from the case at hand. His performance demonstrates a belief that English precedents could be of value in convincing a court, even if on this occasion he lost after a special verdict by the jury, which effectively permitted the judges to decide whether or not the contents of the book published by Checkley in defense of episcopacy were libelous. This action by the jury was surprising in such a sensitive and sensational case, although it did acquit Checkley on one part of the indictment. Read had argued that the judges did not have the power to decide whether or not the book was a libel; only a jury could do this.870 In this instance the bench found Checkley guilty of publishing and selling “a false and scandalous Libel.”

Various English legal sources were evidently more readily available in Massachusetts after the middle of the eighteenth century, as the Legal Papers of John Adams amply demonstrate. Chief Justice Hutchinson, who was appointed in 1760, told a grand jury in 1768 that for the previous seven or eight years he had made it his “constant Practice to read every Book upon the Crown-Law I could meet with.”871 At the Suffolk Assizes in August 1763 James Otis, Jr., quoted Hawkins’s Pleas of the Crown during his successful defense of a husbandman accused of assaulting a deputy sheriff.872 At the same Assizes in August 1764 Benjamin Kent made a legal argument on the acceptability of a convicted woman as witness for the defense, quoting various authorities, while successfully defending a man and woman charged with theft.873

The first recorded special verdicts at the Assizes occurred in the early 1720’s. Their use suggests that the jurors were acting on their own initiative or at the suggestion of experienced lawyers rather than simply on the instruction of the judges. Jurors probably carried over the practice from civil cases. For example, at Plymouth Superior Court on 1 May 1719, the full bench heard arguments from Auchmuty, Read, Valentine, and Robinson on a special verdict by the jury in William Thomas’ case of entail. At issue was the status of Plymouth laws after Plymouth ceased to be a separate colony in 1691. The bench advised for one whole term before reaching a decision in April 1720 in favor of Thomas, with Justice Lynde alone in the minority.874

Special verdicts in criminal cases during the 1720’s were of two kinds: those in which special verdicts identified legal problems of some moment and those in which juries appear to have abdicated decision-making powers in controversial cases. At the trial of Daniel Tuttle for counterfeiting at Boston in 1723, the special verdict revolved around the legal definition of “uttering” a bill of credit that was counterfeit. When the accused offered the bill in payment for some goods, he specifically encouraged the recipient to verify its genuineness if she so desired. When the woman found the bill to be counterfeit, the purchase fell through. The judges had to decide whether the “Producing, Offering and putting the aforesaid bill into the hands of Mrs. Ellis by the said Daniel Tuttle be Deemed an Uttering by the Law of this Province upon which he stands Indieted.”875 The bench heard legal argument from both the Attorney General and counsel for the accused, who is not identified, before acquitting Tuttle. Although the judges may have been pressuring juries to return special verdicts, and thus occasionally transferring the power of conviction or acquittal into their hands, it is equally possible that lawyers for the accused were persuading juries to reach special verdicts under certain circumstances and then trying to use legal arguments to persuade the judges of the merits of their clients’ cases.