Law and Authority to the Eastward: Maine Courts, Magistrates, and Lawyers, 1690–1730

NO history of law in colonial Massachusetts would be complete without some examination of the administration of justice in that region which the authorities in Boston were accustomed to call “The Eastern Parts.” Although Maine’s earliest beginnings form a distinct chapter in the colonial American experience, the history of the State itself dates from the separation from Massachusetts in 1820. For more than a century and a half between those events, Maine was a part of The Colony, Province, and Commonwealth of Massachusetts. From 1651, with only brief interruptions, the laws enacted by the General Court had force east of the Piscataqua River, representatives of the Maine towns travelled up to Boston as deputies, and members of the area’s leading families sat at the Council Board. County courts in Maine administered justice according to the same forms that governed judicial procedure in Suffolk or Essex or Hampshire Counties; and after 1692, from the days of Judge Samuel Sewall in 1700 to those of lawyer John Adams in the decade before the Revolution, the justices of the Superior Court, with their attendant lawyers, clerks, and servants, travelled the eastern circuit. The legal and institutional history of the old District of Maine is thus very much a part of Massachusetts legal and institutional history.984

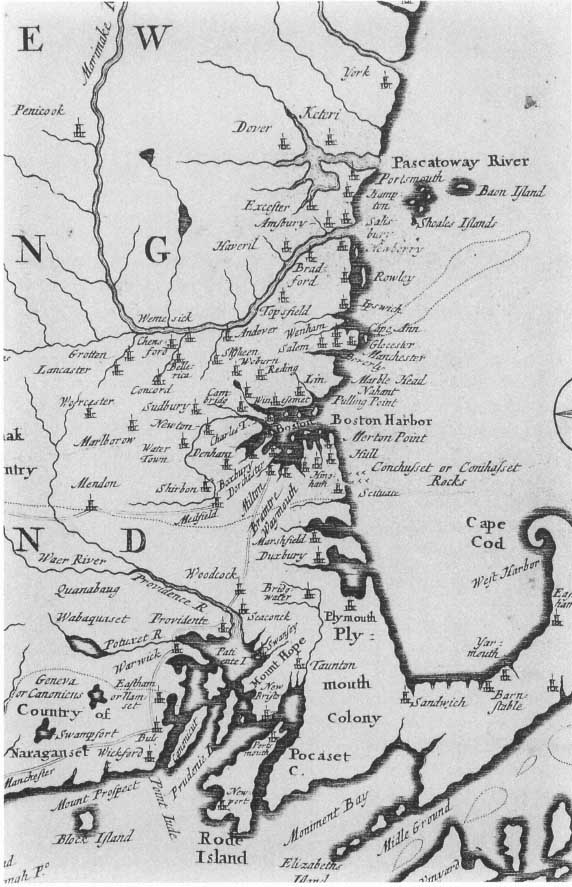

21. Portion of “An Exact Mapp of New England and New York” showing the “Pascatoway River” [Piscataqua] from Cotton Mather, Magnalia Christi Americana (1702).

Yet law and authority in Maine reflected differences that had early marked off this region from the Puritan colonies to the south. The proprietors of the Maine and New Hampshire lands had failed to establish direct, personal authority or a lasting scheme of government. Thus the planters and servants who had come over in the 1630’s and 1640’s to fulfill the plans of Gorges and Mason were soon left to their own devices. They found leaders from their own ranks, or from among those who were soon attracted to the “Eastern Parts” as dissenters from Puritan orthodoxy or economic opportunists. Most of these men adjusted readily to the changes that came with Massachusetts rule in the later seventeenth century, although the traditions of government by a few dominant families persisted.

The area was also more exposed. During the period on which this paper will focus, 1690 to 1730, Maine was, indeed, a kind of “eastern march” of the Province. An Act of March 1694/5, entitled “An Act to Prevent the Deserting of the Frontiers,”985 indicates the concern of the government in Boston to stem the flow of refugees from Indian raids that threatened to weaken dangerously the fragile and extended defenses of the eastern settlements. Such a law only re-enforced a pattern of authority that had existed from the earliest days of settlement, a pattern that saw, by 1690, the emergence of dominant families, whose members exercised exceptional authority and enjoyed a high degree of local prestige. These men and their descendants bore heavy responsibilities of both a civil and a military kind. They dominated the official life of the region during a large part of the eighteenth century, and established little dynasties of power. Their members for three or four generations were prominent in the affairs of church, town, and county, and as garrison holders and militia officers they were important to the security of the region.

During this period the history of the Maine settlements cannot be separated entirely from that of the neighboring province of New Hampshire, which lay directly across the Piscataqua River. Until Falmouth (later Portland) and the region from Casco Bay to the Kennebec began to equal Kittery, York, Wells, and Berwick in importance, the official life of this part of Massachusetts Bay overlaps that of New Hampshire. The ruling families of York County and adjoining Portsmouth, New Hampshire, constituted a Piscataqua establishment. The largely unprofessional lawyers who appeared in the Maine courts of the early eighteenth century were often from the west side of the river; and frequently enough the equally unprofessional judges of those courts were linked by both family and business ties to New Hampshire. In short, the historian of the region can discern a pattern of authority that seems to have endured well into the middle of the eighteenth century. Perhaps that keen observer, John Adams, writing home to Abigail from York in June 1774 on his final journey on the eastern circuit as a lawyer, is a good witness to the lasting importance attached to the magistrate’s place and functions. “The Office of a Justice of the Peace,” he wrote, “is a great acquisition in the Country, and such a Distinction to a Man among his Neighbours as is enough to purchase and corrupt allmost any Man.”986

The Legal Profession in Maine

During the late fall and winter of 1707–1708, John Bridger, Queen Anne’s Surveyor of Woods and Forests in America, set out to enforce the existing laws against the unlicensed cutting of mast timber in the great white pine stands of the Piscataqua region. With a small armed guard Bridger made at least two forays into the country just west of the small Maine and New Hampshire settlements. On the eastern (Maine) side of the river, about thirteen miles above Salmon Falls, Bridger found, in late November, four Kittery men in the process of cutting and felling “Six mast trees that would make Masts from twenty-eight to thirty-two inches Diameter.” On 7 December he apprehended, near Exeter, New Hampshire, seven cutters at work. Bridger’s information to the New Hampshire Court of Sessions the following March alleged that the woodsmen, employed by John Plaisted, “Did Cutt, fell and Destroy Nine white pine trees one of which was marked with a Broad Arrow.”

Bridger’s actions in that season bespeak a clear intention to give effect to his authority.987 He moved as quickly as possible to prosecute offenders in both New Hampshire and Maine. He wished particularly to punish the powerful men who were the real culprits. He attempted to arrive at the Maine court—the Court of General Sessions of the Peace for the County of York—in time to lodge his information about the November cutting at its January sitting. But distance, the elements, and lack of cooperation thwarted him:

I then took up the workmen and bound them over to appear at the next Court, [he wrote to the Lords of Trade in March] which obliged me to go to Boston to take advice from the lawyers. This was in the extreamest cold weather as ever I knew. I froze my face and neck many times this winter. The snow and cold caused me to miss the Court at York by two hours, but the case was continued till Aprill.

He pleaded for support, both financial and moral: “These trialls will cost me a great sum,” he complained, “and no lawyers but at Boston.”988 It would be tempting to dwell at greater length on Bridger’s problems, for they are part of an episode that has its own interest. But it is Bridger’s last point—“and no lawyers but at Boston”—which sets the theme here. The records seem to support Bridgets statement as essentially accurate for the first decade of the eighteenth century; it is hard to identify anyone in the Piscataqua region who, even by the most generous use of the word “profession,” could be called a lawyer. Certainly no one was primarily earning his livelihood from the meager pickings that the law allowed those who acted as attorneys or advocates. But a number of readily identifiable men were providing their neighbors with practical legal advice, were drafting wills or drawing deeds, and were, as needed, appearing before the courts as advocates with some regularity. Thus, although Bridger was, strictly speaking, correct, to leave his statement as conclusive would be to miss an interesting and picturesque part of the history of the practice of law in colonial New England.

While the focus of this paper is on the decades between 1690 and 1730, it might be of some interest first to look briefly at the evidence for the presence and influence of lawyers during the age of beginnings—when Maine was Sir Ferdinando Gorges’ Province, and not the “eastern March” of Puritan Massachusetts.

William Willis, in A History of the Law, the Courts and the Lawyers of Maine more than a century ago, noted that Thomas Gorges, a young cousin of the Proprietor, was the first educated lawyer in the region that later became the State of Maine.989 There seems little reason to revise that view. When Gorges came over as Deputy Governor in 1640, he had been a law student for two years. Robert Moody’s recent edition of Thomas Gorges’ Letters990 reveals a sensitive, thoughtful young man, who was certainly concerned not merely with the technicalities of current English practice. We glimpse in these too brief and incomplete copies of the letters that Thomas Gorges wrote home a man interested in the larger problems of government, one who was, in addition, sensitive to the liberties of the subject. “I could wish I had my law books, which I left in England,” he wrote to his father shortly after he reached Maine, “for I studdy law and have more and more need to use it then ever I had.”991 He was still pressing to have the books sent over three months later. It would be a year before they reached him.

In response to a suggested prescription for a “way of government” from Sir Ferdinando, Thomas noted that “in my opinion [it] is conformable to the laws of England and suitable to the times heer,” but he was quick to point out that the detailed provisions for the frequent sitting of Courts needed to be modified in light of the sparse population and the rigors of the climate.992

Even more striking are the evidences of Thomas’s concern that the laws of the new plantation should reflect the reforming views of the age. “I think we should be very cautious for the punishing of theft with death,” he wrote in the fall of 1641. “Sir. Tho: Moors Utopia hath good rules for it.”993 On the matter of a religious establishment, he noted in the same letter:

We are in hopes of settling the ministers in the province but if you tye men strictly to the government of the Church of England all will goe to wracke. You must of necessity tolerate liberty of conscience in many particulars. Nothing hath hindered your parts but this, and want of government, and I wish that our Laws here will [en] able true men to undertake it.994

To an apparent suggestion from Sir Ferdinando that trial by jury be limited or repressed, Thomas wrote in cautious terms in December 1641: “Whether putting down Juries be not barringe the Subject of his liberty, I leave to your consideration.”995 And the next spring, speculating on the possible use of Negro slaves, he wondered if “theyr bodyes can agree with the coldness of the country.” Though he tentatively thought that if so, “they would be excellent,” he followed that with the interesting statement: “ . . . I believe I could frame an argument against the lawfullness of taking them from theyr own country. . . .”996

Finally, this young man shows himself to have been a sensitive and informed student of the political theory of his age. In a letter of December 1641 he comments on the New Hampshire settlers’ voluntary submission to the authority of Massachusetts, which had recently taken place. “The Bay have taken the South side of the Pascattaway river uppon the peoples request, for the want of good government; so they [the Massachusetts authorities] have done it partly by virtue of theyr love and partly by the peoples desires, supposing themselves bound to shelter those that looke to them by the law of nations and nature.”997

Thomas Gorges was to be in Maine for a scant three years. In the decades after 1650 the struggling settlements offered small scope and less attraction for lawyers. Yet even in that period there was need for the practical management of both public and private business. In Maine, as elsewhere in the English colonies, the law ruled. Courts needed to be set up and staffed, a criminal justice system established, deeds executed and recorded, indentures drafted, and wills drawn. If in the circumstances of time and place these matters did not call for skilled or learned lawyers, they did require men of experience, energy, prudence, intelligence, and probity. An outstanding example of those who emerged to meet the needs of frontier law in seventeenth-century Maine was Edward Rishworth (1619–1690).998 He was a member of the important and intellectually distinguished Hutchinson family, grandson of the matriarch Susannah Hutchinson and son-in-law of the Reverend John Wheelwright. Rishworth was Recorder of the Maine courts (in the clerical rather than judicial meaning of the title) from 1651 to 1686, save for two years. He served impartially under the successive governments of the period, and though Charles Thornton Libby wrote that he was termed a “turncoat,” the charge seems too strong, and probably unfair. During much of that time he was also a sitting magistrate; as Libby continued, “the page was white under his pen until a sound judgment had been reached.” Libby added, “While evidently not bred to the law, the urge in his nature to see things go right developed him . . . into a sound lawyer.”999 In addition to his public functions as clerk and judge, it is clear that Rishworth served also as a practical legal adviser and drafter of legal papers in private matters.1000 He was an outstanding early example of a type at its best that was to serve the region for two generations after 1690.

Who were the Maine magistrates of these years?1001 Neither time nor space allows an extended discussion of the question, but a summary view is useful. In Kittery, three families dominated official life in the period: the William Pepperrells, father and son, merchant shipowners with their homes and businesses at Kittery Point; the Frosts, whose homestead at Sturgeon Creek in the upper part of the town had been settled by the immigrant Nicholas Frost by 1640 and was to remain in the family for over three centuries; and the Hammonds, neighbors and relatives of the Frosts, who by 1700 had already established a near monopoly of the office of Clerk of the Courts.

In Berwick, the Plaisteds dominated affairs. Active in lumbering and milling, the brothers Ichabod and John Plaisted were frequently willing to use high public office to further private ends. At a time when Ichabod was a deputy mast agent under the Crown, brother John was busy cutting white pine above the dimensions permitted by the charter provisions and was successfully defying authority. When, in 1708, John Bridger, the Queen’s Surveyor-General of Woods, sought to prosecute four of Plaisted’s men for unlawfully cutting mast timber, John and Ichabod were both members of the York County Court of General Sessions that tried the accused men. At one time John Plaisted was a magistrate in both Maine and New Hampshire, and the family had close ties, in business, in official life, and by marriage, to leading figures in New Hampshire.

In York the Prebles, descendants of Kentish yeomen, were leaders of the town in the later seventeenth century and on into the eighteenth. The first Abraham Preble, a carpenter, was in Maine by 1639 and established the family tradition of office-holding. His son, another Abraham, from the 1660’s followed a typical colonial cursus honorum: constable, many times selectman, deputy to the General Court, militia officer, and a justice of the peace in the first commission under the second charter. His nephew of the same name carried on this tradition of public service until the nephew’s death in 1724. The Prebles of this period were active, energetic men of affairs, but they did not achieve the social eminence or economic power of Pepperrells, Frosts, or Plaisteds.

In Wells, the preeminent governing family was that of the Wheel wrights. By 1643 the Reverend John Wheelwright had moved to that town from Exeter, New Hampshire. His son Samuel (d. 1700) and Samuel’s son, Colonel John, were the squires of Wells until the latter’s death in 1745. Since, from the 1680’s until the end of Queen Anne’s war, Wells was on the eastern edge of the Province, Colonel John Wheelwright’s duties were correspondingly heavy and dangerous.

Marriage linked nearly all of these families, giving substance to the term “establishment.” The Pepperrells and Frosts were closely bound; evidence from later in the eighteenth century suggests that this produced considerable family pride. Judge Simon Frost, writing to a friend in 1746, complained that “there were people who did not show him that respect which was his due, in regard to his Honorable and Worthy Ancestors.” The Plaisteds formed marriage alliances on both sides of the Piscataqua; Ichabod’s son, Samuel, was married to Hannah Wentworth, daughter of Lieutenant Governor John Wentworth of New Hampshire. Samuel’s cousin, Elisha, son of John, married Hannah Wheelwright, the daughter of Colonel John. The Hammonds were, as noted, closely related to the Frosts; the first Joseph Hammond (d. 1711) had married Catherine, daughter of Nicholas Frost. Thus, the Frosts and Hammonds of the period under consideration here were cousins.

This kind of pattern might be expected in a small and relatively isolated society. What is perhaps more significant, and is certainly interesting in the context of this study, is the creation of family traditions of office. William Pepperrell, Jr., was serving as his father’s clerk in court by his sixteenth birthday,1002 and as a young man, succeeded to judicial office. Joseph Hammond, Sr., and his son by the same name were clerks of the courts from 1694 to 1720. The elder Hammond had been “clerk of the writts” in Kittery since 1673, and the family tradition began even earlier when Joseph’s father, William Hammond, the immigrant, was clerk of the writs in 1668 in Wells, where he had first settled.1003 Although other examples might be given, one striking instance of a family’s domination of office will suffice. From 1724 until the Revolution, the High Sheriff of York County was a Moulton.1004

During the period which followed the establishment of government under the second charter, at least three groups of persons can be identified as providers of legal services in Maine. First would be those who were admitted to practice in the courts in accordance with the provisions of the Massachusetts statute of 1701, “An Act Relating to Attorneys.”1005 Their names are to be found in the York County court records; most of them, however, were not residents of Maine at all but of New Hampshire. Prominent were John Pickering of Portsmouth; Charles Story of New Castle, for many years secretary of the Province of New Hampshire; Benjamin Gambling, a Harvard graduate in the class of 1702 who had migrated to Portsmouth from his native Roxbury; and Thomas Phipps, another Harvard man, class of 1695, who had come down from Boston to Portsmouth as a schoolteacher the year after his graduation. A second group consisted of those Boston lawyers who frequently followed the Superior Court on its eastern circuit, and who sometimes served as counsel for Maine persons of large interests. Finally, one must include residents of York County who, though not recorded as admitted to practice, nevertheless appeared as advocates or counsel in the courts.

Of the first group, John Pickering was over fifty years of age when he took the attorney’s oath at the York court in January 1701/2. His career amply supports Jeremy Belknap’s description of him as a man of “rough and adventurous spirit,” and Page’s later judgment is that he was a person of little education “though of much force.” Pickering was a carpenter and miller with interests in mills in York, and was the owner of property there. His public career took him to the speakership of the New Hampshire Assembly and by 1700 to the position of Crown Attorney. He was holding the latter office at the time Bridger was prosecuting John Plaisted’s mast cutters in 1708; but in the York court of April in that year, Pickering, who was Plaisted’s father-in-law, appeared as counsel for the defendants. His answer to Bridger’s information was shrewd, forceful, rough-hewn, and even by the standards of that somewhat casual age, replete with strange spellings.1006

Charles Story had come to New Hampshire as Proprietor Samuel Allen’s appointee for the posts of provincial Judge of Admiralty and Secretary. The first position he never filled, and the second he lost for a short time because he failed to deal tactfully with the Council. He had refused to attend a meeting called soon after he arrived from England, and had answered the Council’s request to meet with them “with lofty indecent carriage.” But he made his peace, adjusted to what was surely at first an uncomfortable environment, and became an established figure in the region. He was active in the courts on both sides of the river until his death in 1715. Story seems to have been familiar with English law, and as one who had been sent over to serve as an admiralty judge, may well have been trained in the civil law also. Bell, in a footnote in Volume II of New Hampshire Provincial Papers (670), suggested that Story might have studied at Doctors’ Commons. In the records of the York courts, Story’s performance bears out these necessarily somewhat tentative judgments. He was at times a stickler for precision and technicality of process; and the reasons of appeal which he drafted often indicate some knowledge of substantive rules as well. In a case of 1705 (Mainwaring and Frost v. Shores in the Inferior Court of Common Pleas in York), Story, representing the appellants, argued closely for a reversal on the grounds that the action was brought as trespass on the case, whereas it should have been detinue since the action had been brought for the recovery of a chest and contents and one of the defendants at trial was the wife. “By the Common Law,” Story urged, “the wife cannot be a detainer, but the Husband.” Further, he pointed out, the appellee Shores had failed to state adequately and precisely the facts on which his claim had been based. The contents of the chest (“Cloathes”) had not been particularly described nor had their value been stated, as law required; nor had Shores stated exactly when the detention had taken place.

Benjamin Gambling and Thomas Phipps took their places in New Hampshire official circles soon after 1700. They both married into the Portsmouth ruling group. Gambling’s wife was Mary Penhallow, whose father, the historian of the Indian wars, sat on the Superior Court bench; and her brother John, the factor at Georgetown after 1715, became a York County justice of the peace in 1718. In Maine, Gambling was frequently counsel for appellants to the Superior Court, and his work as a drafter of reasons of appeal suggests acuity and at least some familiarity with the technicalities of the law.

Thomas Phipps had come down to Portsmouth in 1696, the year after his graduation from Harvard. He was lured by the town’s decision to hire an “abell schollmaster,” one “not visious in conversation.” He too married well; his first wife was Eleanor Cutt, widow of a substantial merchant. By 1704 he was a justice of the peace in New Hampshire and became active in official life. Before 1712 his first wife had died, for in the spring of that year he married another widow, Mary (Plaisted) Hoddy; she was the daughter of John Plaisted. Phipps’ rise from the schoolroom to high office was fairly impressive, but it did not take place without some troubles along the way. As sheriff, and later as King’s attorney in New Hampshire, he was charged by his enemies with padding official expenses and neglecting his duties. When asked why, as King’s Attorney, he had not seized a parcel of stolen masts, Phipps is said to have retorted that “Inasmuch as the King has commissionated an Officer to inspect the King’s Woods . . . it appears to be his business and not mine. . . .” Phipps, like Gambling, was a knowledgeable, acute, but essentially self-educated lawyer.1007

Less frequently present in the Maine courts, and then usually serving as advocates for appellants in important cases, were members of the still embryonic Suffolk County bar. Paul Dudley, Thomas Newton, John Valentine, and Addington Davenport, Jr., appeared in York from time to time when the Superior Court was travelling the eastern circuit.

Others who took the oath and were admitted to practice in Maine courts were residents of York County, but their effectiveness seems not to have been very great, nor their reputations such as to attract important clients, even in that simple society. A Kittery man, Lt. Richard Briar, took the oath in 1701. Of a social rank somewhat lower than that of the established families of the region, Briar appeared infrequently, and then not impressively, in the York courts. He probably served as his own lawyer in an almost Dickensian episode touching a pair of missing mittens in April 1704. Shortly after that, he had left Maine. Another local person, Nicholas Gowen, was admitted in 1703. One of his sons, James, was destined to sit on the York County Inferior Court bench later in the century, but Nicholas achieved no great eminence. He was a man of practical bent, a surveyor and scout, and a sometime deputy from Kittery to the General Court. Though connected to the Frosts, he was not highly regarded by some of that family. His uncle, Major Charles Frost, testified in January 1695–6 that Nicholas was accounted a “busy body” who concerned himself with matters that did not affect him. Although he lived until 1742, his role as a lawyer was, on the evidence, minimal.1008

Still others acted as agents or attorneys or gave legal advice, even if they had not been formally admitted to practice in the courts. One who can be readily identified was the Kittery surveyor, William Godsoe. He was frequently called on for advice in situations where title to land was at issue, or where rightful possession was challenged. The York files for the period contain many papers from his hand or references to his testimony in such cases. Not only did Godsoe often appear as a kind of expert witness in these matters; he was also the author of reasons of appeal, or answers to such reasons, in cases that were carried to the Superior Court. Thus, in 1717 Godsoe served as a de facto lawyer for a neighbor, John Shepard, who was the appellee in a bitterly contested case brought by Samuel Spinney. At trial Shepard had prevailed; but Spinney appealed, and Godsoe prepared Shepard’s lengthy “answer” to Spinney’s reasons of appeal. It is an interesting document and clear evidence of the existence of lay participation in the legal process. Godsoe’s rambling, colorful argument also surely tells us something about courtroom exchanges; it is hard to escape the feeling that this was meant to be delivered aloud in court. In arguing Shepard’s case, Godsoe invoked for authority Euclid (in defining a line); local gossip (as to Spinney’s reputation for honesty); and the “Proverb first come first serv’d.” The peroration embodied some powerful invective: Spinney is a frivolous litigant; “he acts the part of a Child that has been parted with a Ba[u]ble.” He is a constant thorn in the side of his neighbors: “som Lands he snips att the ends and squesed others in the side . . . to screw out a few Poles of Land that people had Injoyed many years.” Such documents are vivid echoes of grass-roots litigation.1009

Finally, one should certainly include in this description of the legal world of colonial Maine examples of those more eminent men who, usually officeholders themselves, also served on the side as advisers, as drafters of legal papers, and as givers of legal opinions. Like Edward Rishworth earlier, the magistrates of the period after 1690 were often found in these roles. Joseph Hammond, Jr., clerk, county treasurer, and justice, frequently served as a lawyer in fact, if not in name. William Pepperrell, Jr., was the drafter of legal papers of a routine kind, as were the Frosts and Wheelwrights. These men needed to have a grasp of such law as defined their property interests and business engagements, and they often relied on that knowledge to protect their own concerns or those of neighbors and friends.

How familiar with legal authorities were these frontier magistrates and lawyers? We have scant evidence. Certainly the Boston men, Newton and Dudley, had professional training. Dudley, with John Read, is said to have encouraged special pleading; and Washburn wrote that when Thomas Newton died in 1721, he had owned the largest and best collection of law books ever offered for sale in Massachusetts.1010 Charles Story, as has been noted, was probably an educated lawyer also.

But the York County justices and lay lawyers of the early eighteenth century were certainly self-educated and in varying degrees. Some, indeed, were concerned to attain as much competence and understanding as their remote stations and harsh life would allow. When the second Charles Frost was buried in 1724, the Reverend Jeremiah Wise eulogized him in this manner: he was, Wise said,

a Man of great natural Abilities and did excel in a clear Head, a solid Judgment and a very tenacious Memory. . . . He was considerably studied in Mathematicks, Natural Philosophy and History, but he did excel himself in the knowledge of English law, as did well become a Gentleman of his Character.1011

It would be rash to read too much from this; yet Wise doubtless had some basis for his appraisal of Frost’s knowledge and abilities. Circumstantially it seems certain that Charles Frost had acquired some law books beyond the current editions of Province Laws or Dalton’s Countrey Justice. The inventory of his estate carries an item of £120 for “Books,” a figure far larger than any other I have seen for that period in Maine. Unfortunately, the appraisers did not list titles, nor even indicate categories. We know that Frost’s cousin, William Pepperrell, Jr., ordered law books from England when, in 1729, Governor Belcher named him chief judge of the York County Inferior Court of Common Pleas, and there are scattered references to collections of reports and treatises in pre-Revolutionary Maine.1012 But specific information is lacking, and only occasionally does a particular title appear. It is perhaps interesting that James Menzies, who was a lawyer in Essex County and appeared in the New Hampshire courts in the early eighteenth century, owned a copy of William Sheppard’s well-known tract on the reform of the common law, England’s Balme, published in 1653.1013 The Puritan zeal for law reform was not unknown in New England.

Not until the years just before the Revolution was there a Maine bar of any stature or consequence; even then, it had few members.1014 But to suggest that the unprofessional lay lawyers and justices who preceded them had any significant influence on these later developments would be asking too much of the evidence. Certainly men like Richard Briar, Nicholas Gowen, or William Godsoe fall into that group of “pettifoggers” who were castigated by the young John Adams.1015 And the Plaisteds of the time seem often to have regarded public office as a private convenience. But we should remember, too, men like Charles Story, Charles Frost, John Wheelwright, the two Joseph Hammonds, and the future Sir William Pepperell. Learned they were not, but as clerks, magistrates, or legal advisers and attorneys they were shrewd, experienced, and, on the evidence, fair.

In March 1708 Nathaniel Raynes of York, a Quaker, complained to Governor Dudley that the Inferior Court of Common Pleas at York had awarded judgment against him by default. Raynes had not appeared. He argued that he had been near the courtroom all the time, but had not been notified when his case was called. Joseph Hammond, Sr., who was the chief judge of the court, wrote to Dudley about the episode at length. Pointing out that the judges had delayed other business for some time while waiting for Raynes, Hammond added: “let him be what he will, he ought to have Justice done him. Cap’t’n Wheelwright Informs me that they waited for him a great while after the Case was called & sent the officer into every roome in the house to enquire for him. . . . I believe theres not a man of the Court but are desirous it Should come to a fair tryall, that the Merit of the Case might be inquired into; undoubtedly Raines will be extreamely wronged if he Should pay so much as Judgment went against him for. . . .”1016 More than a century later Williamson would write that Hammond was a “man of great integrity and worth, whom the people held in high estimation. He left a son of the same name, the worthy heir of his virtues. . . .”1017 The York County records of the period would bear this out. Perhaps the Hammonds, who were simple husbandmen, should stand as the best representatives of law and authority in the “Eastern Parts.”

A Day in Court: A Reconstruction of the Court of General Sessions of the Peace for York County, 6 July 1725

This survey of the early history of Maine magistrates and lawyers would not be complete, certainly not satisfactory, if it did not include a picture of what really took place when courts met and the rule of law—even in this simple society—was given effect. Fortunately the Maine court records are a rich source of information for the historian who would seek to fill out that picture.

On Monday afternoon, 5 July 1725 the frontier village of York in the Province of Massachusetts Bay would be beginning to fill up with all those whom official duty, stern coercion, or mere curiosity drew in for the quarterly sitting of the Court of General Sessions of the Peace, to be followed by the July session of the Court of Common Pleas. The larger events which must have dominated tavern talk in that summer of 1725 no doubt gave way to “discourse” about the cases pending before the courts. Temporarily at least the topics of conversation must have shifted from the recent defeat of Captain Lovewell’s little force near Pigwacket village or the coming conference with the eastern Indians at St. George’s, to speculation about the bitter litigation that was splitting loyalties in the Frost-Hammond-Leighton families in the upper part of Kittery; or to the charges that had been brought against Daniel Morrison and Malachi Edwards for their “Threating Speeches” and “Contemptuous Manner” at the Wells town meeting two months earlier. What went on in the courts attracted a great deal of attention in a small community like York village, and except for those whose services were indispensable elsewhere, it is not difficult to imagine that virtually the whole population of York was attracted to the events surrounding the holding of the courts.

By evening as many as sixty or seventy persons would have come in to York.1018 The horses of those who had ridden overland would be in temporary stables or at pasture, and the vessels of people who had come by sea at their moorings in the harbor or in the broad reach of York River. Well before sunset on that long summer day the taverns would be filling up, and the houses of substantial townsmen (Prebles, Banes, Moultons, Simpsons, Cames) would be the scene of more genteel entertainment; for the families of this rural “establishment” were closely related, and the quarterly sittings of the two county courts afforded welcome opportunity for social gatherings. Perhaps the Reverend Samuel Moody was pondering the court-week lecture that he would be delivering the next morning, and doubtless the under-sheriff, Benjamin Stone, had installed the simple “platform” that transformed John Woodbridge’s tavern parlor into a courtroom for His Majesty’s justices. By early evening that same room, the adjoining hall and chambers, and the benches outside would become the noisy center of the informal preliminaries, for court days vied with ship launchings, militia musters—and Cambridge commencements—as occasions for large-scale and often turbulent celebration.

On this particular evening that was certainly true, and Woodbridge’s tavern was the scene of a brawl that had its inevitable sequel the next morning. Nay, more; one of the principals in this picturesque episode was John Woodbridge himself. For neither the first nor the last time the court’s host was to find himself in the slightly ridiculous position of standing charged with an offense in his own tavern parlor, before a company that included, besides the justices and other officials, a good number of his friends and neighbors. Although some details of the disturbance that broke out that evening of 5 July escape us, its main outlines are vivid enough. One of those who had come in to face charges at this court was John Smith, a fisherman suspected of uttering a counterfeit fifteen-shilling note. Smith was among the company at Woodbridge’s, and for reasons that are not apparent in any of the records, was either carrying or sitting near a gun. He was also doubtless sitting close to the supply of drink: New England rum was clearly the catalyst that most often precipitated such events. Smith, according to the clerk’s note of the matter the next day, was guilty of “Reveling & disorderly Carriage, in fireing of a gun in the house of Mr. John Woodbridge.” The taverner himself seems to have over-reacted; records from other sittings indicate that he was perhaps too fond of his own staples of trade. At any rate, on this occasion a witness deposed that he saw Woodbridge “coller John Smith & [tell] sd Smith he would knock his brains out if he would not go out of his house.” Smith stood his ground, and Woodbridge proceeded to carry out his threat; the witness testified that Woodbridge “let go his hold & caught up a gun & Strock sd Smith over the head. . . .”

The court records are silent about any other outbreaks that night. By eight o’clock the next morning, however, Smith was lodging a complaint against Woodbridge before one of the resident justices of the peace, Samuel Came. The innkeeper appeared; and Came, after hearing the charge and taking the depositions of two witnesses, bound him over to answer “before the Justices of the Court of Gen’l Sessions of the peace to be holden at York . . . on this day.” It is permissible to hazard the guess that more than one of the participants at this early morning scene was nursing a sore head; gun barrels and rum, if applied with sufficient force or in enough volume, seem equally capable of producing unpleasant sensations. Thus, even before the solemnities of Quarter Sessions took place, the judicial machinery of the county was invoked to deal with this brawl, itself directly related to the gathering of persons for the sitting of the court.

Even in this remote corner of British North America, the authorities were not unmindful of the traditional ceremonies associated with Quarter Sessions and Assizes. Thus, when the justices of the Superior Court came down from Boston in May, they were met at the county line, in this case the Piscataqua River, by the High Sheriff and his deputies, often attended by other gentlemen.1019 While the justices of the county courts would not have been accorded this particular dignity, they did vest their own proceedings with some of the ceremony that custom and the law manuals prescribed.1020 And so, shortly after Samuel Came had bound over John Woodbridge, the justices and other officers probably gathered on the common. To the tolling of a bell, perhaps to the beat of a drum, they marched in procession to the meetinghouse—the sheriff with his wand, the constables with their staffs of office, the justices in their finest clothes. For by a custom that in York County, at least, went back twenty years, the members of the courts would “wait on God in his House before they Entred on Court Business.”1021 The weekly lecture, a fixture in any well-regulated Puritan community, was ordinarily held on Wednesday, but on the four occasions when the courts were meeting, the authorities moved it up to Tuesday morning. We may assume that the pastor at York, Samuel Moody, was the preacher on the occasion. “Frontier parson and fighting chaplain,” he had already ministered to this exposed community since 1698; in July 1725 there still remained twenty-two years of his near half-century of service. What he said on that July morning we shall never know; conventionally such sermons were tailored to the occasion, and one might expect, therefore, that Moody dwelt on the doing of justice. But Samuel Moody was not a conventional parson; he was an eccentric, perfectly capable of startling his congregation with outrageously personal remarks, a spiritual dictator who thought nothing of shooing people out of the taverns or marching into a fellow townsman’s home to “see about” a falling off in family worship.1022 It is not inconceivable, therefore, that he spiced his remarks on 6 July 1725 with some pointed and explicit comments on the events of the preceding evening.

After the lecture the procession formed again and moved to Woodbridge’s tavern. There, doubtless in the best parlor, six justices of the peace for York County took their places on the platform that had been prepared. In front of them, or to one side, quill sharpened, was the new Clerk of the Courts, young Charles Frost. Perhaps behind them on the wall was fixed that “Coat of the King’s Arms” which, ten years later—when the County had its own courthouse at last—Samuel Came and Jeremiah Moulton were directed to purchase, if they could, from John Woodbridge.1023

The court on that July morning consisted of six of the ten persons who were active in the Commission of the Peace for York County at that time.1024 The senior in point of service, and probably also in age, was John Wheelwright of Wells (c. 1664–1745), whose interesting gravestone portrait has been reproduced for this volume. The primitive quality of this likeness and the medium only enhance the powerful effect, and suggest the character of the man. Behind the conventional pose and popeyed stare, one glimpses the vigorous, forceful magistrate and soldier who for more than four decades was one of the two or three most influential figures on the exposed eastern frontier of the province. Perhaps Wheelwright had inherited from his grandfather, Winthrop’s famous antagonist, both the strong frame and the sturdy spirit. The Wheelwrights of these years were a remarkable family.1025

Equally well known to contemporaries was the next senior justice of the peace, Joseph Hammond of the “upper part” of Kittery, later the town of Eliot. He was the second bearer of that name to serve as Clerk of Courts, Justice of the Peace, and Judge of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas. His grandfather, William Hammond, had been an early settler of Wells and clerk of the writs there in the seventeenth century. William’s son, the first Joseph Hammond, had been a man of commanding abilities. The second Joseph, who sat down in Woodbridge’s tavern with his fellow magistrates that July, was thus the heir to a long tradition of public service.

Up from Casco Bay had come Major Samuel Moody. Related distantly, if at all, to the York minister of the same name, Major Moody was the second founder of Falmouth, later Portland. A graduate of Harvard in the class of 1689, frontier preacher turned soldier-magistrate, Moody must have dominated the resettled regions north and east of the four old towns. That he was not accorded the fullest measure of loyal affection is unhappily clear, however. Two years after this court of July 1725, Moody was to lodge a sharp complaint against Benjamin Wright, a fellow-townsman. Wright, said the Major, had “abused and Scandilised him as a Justice of the Peace.” When Lieutenant Governor William Dummer visited Falmouth earlier, Moody had sent out orders for a number of people, including Wright, to “Attend in Arms.” Wright was quoted as saying “he was very ready to wait on his Hon’r but would not do it by Old Beelzebub’s Ord’r.”1026 Like his fellow magistrates John Penhallow at Arrowsic and Joseph Heath at Richmond, Moody was under a constant strain to maintain order over the still largely masculine, transitory, and rootless population of the region east of Wells.

Joseph Hill, brother of John Hill, who had served on this court briefly from 1711 to his death in 1713, was from Wells. Hill, like so many of his colleagues, was active in military affairs during these times. He first came on the court in April 1722. Though he was over fifty years of age in 1725, he had had less service in civil affairs than the other justices. John and Joseph Hill’s father, Roger, had been an early settler of Saco. Indian troubles, probably, account for John’s removal to Kittery and Joseph’s to Wells after 1700. Joseph Hill, like his fellow townsman, John Wheelwright, had a special interest in two of those who were to come before the court this day. Daniel Morrison and Malachi Edwards had been charged by the two Wells justices with disrupting the town meeting in that place two months before, and that disruption had included, on Edwards’s part, open defiance of orders given by the magistrates.

Samuel Came we have already seen presiding as a resident justice of the peace over the hearing into the brawl at Woodbridge’s tavern. In July 1725 he was already about fifty years of age; but very few of those present in York on that summer day—and those few could only have been young people or children—were destined to outlive him. Came’s life spanned a major portion of Maine’s pre-Revolutionary history, and he was an active participant in the public affairs of town, county, and province for over sixty years. He died 26 December 1768 in his ninety-fifth year.

The youngest member of the court was the bearer of the most distinguished name in Maine’s colonial history. William Pepperrell, Jr., had just turned twenty-nine in July 1725; but since at least his sixteenth birthday he had been acting as clerk to his father, as papers in the York court files reveal, and he had served as clerk of the two county courts since January 1720–1721. He had been a justice of the peace and a member of the court since July 1724. Thus Pepperrell had combined the work of justice and clerk for a full year, for it was only at this July court that the younger Charles Frost took his place as clerk for the first time. Pepperrell’s career as merchant-shipowner and later, as a military commander, Province Councilor, and judge, have obscured his long apprenticeship in public affairs, and particularly his activities as clerk and magistrate at the county level. Despite a busy life as heir to important commercial enterprises, Pepperrell, like his father, was an active and conscientious magistrate, as the records of these years make abundantly clear. In July 1725, too, he assumed his place as one of the four judges of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas.

The grand jurors took their places, perhaps on benches which at other times were occupied by Master Woodbridge’s customers. Fifteen of them had been elected at the annual town meetings in March and in April had been sworn to office “for the year Ensuing.” Thirteen of their number were present on 6 July.1027 The newly settled communities east of Wells had sent in one, or at most two, jurors to this court. But the four old towns were well represented: four from York, including the foreman, Jonathan Bane; three, possibly four, from Kittery; three from Wells, and probably two from Berwick.

23. A deposition of 2 July 1725, York County Court Records. The body of the deposition is in the hand of William Pepperrell, Jr. The signature of the deponent, Samuel Hill, is attested by both William Pepperrells, junior and senior.

Other officers were there, too; the High Sheriff, Jeremiah Moulton, who only a year before had been organizing his company of militia for the great attack on Norridgewock; Daniel Simpson, the new County Treasurer; the coroner, Joseph Curtis; and a cluster of town constables, selectmen, informers, and lesser fry. The clerk’s record does not indicate that the members of the “Grand inquest” were sworn to office again; presumably once, in April, was enough. Nor is there mention of any grand jury charge by Justice Wheelwright, the senior member of the Court. Charges to the grand jury were customary, however; they were a regular part of the formalities of Superior Court sessions, and possibly, too, of the Sessions of the Peace. We will not err greatly, then, if we re-create a scenario that included a formal proclamation by the Clerk that the Court of General Sessions of the Peace, for and within the County of York, was now in session; and a brief, pointed charge to the grand jurors by John Wheelwright, that touched not only their duties in general, but pointed out particular matters that were to come before them.

Institutional history too often suffers from depersonalized treatment. We read of parliaments, assemblies, government departments, or courts as though statute book or manual could tell us how such bodies really functioned. Too rarely do we listen or observe. Of course, valid generalization must rest on a broad range of data; history is not written out of scattered anecdotes or random episodes. But in addition to studies based on a systematic and thoughtful distillation of representative evidence, we need occasionally to let the records speak to us directly. We may know much about how institutions or formal bodies were supposed to function; we can know what contemporary people experienced in such gatherings only if we look closely at the records of actual performances. It is with this in mind that we turn the pages of the ancient court book which Joseph Hammond, Jr., clerk from 1700 to 1720, William Pepperrell, Jr., clerk from 1720 to 1725, and Charles Frost, assuming the position in 1725, filled up between January 1719 and October 1727. Let us start at the point where Frost began his duties,1028 on this July day in 1725.

Charles Frost may have been nervous as he picked up his quill pen, though it was not in character for members of that prominent clan to betray such feelings. Yet Frost may have been aware that his kinsman, Justice Hammond, was figuratively—and perhaps literally—peering critically over his shoulder. For Hammond had served as clerk for twenty years, and it would be unusual if he did not have a proprietary feeling for the position. He knew all the details of that exacting job. So Clerk Frost consulted his notes and Captain William Pepperrell’s record of the last court, and called for James Parker of Falmouth. Parker had been bound over a full year before by Samuel Moody, for selling liquor without license. Term after term he had defaulted, and most recently had failed to appear at April court. Now he was again absent and was declared to have forfeited his bonds of twenty pounds; the clerk was directed to issue a warrant of distress for the bonds, and Parker was further saddled with costs of 35 shillings.

24. Entries in the York County Court Records demonstrating the change of clerks. The top entry is in the hand of Joseph Hammond, Jr., Clerk, 1700–1720, and the lower entry is in the hand of William Pepperrell, Jr., Clerk, 1720–1725.

Turning next to presentments and orders from the April court, the justices first dealt with two matters that had been initiated then by the hard-pressed minister of Scarborough, Hugh Henry. Samuel Libby and Job Burnham, the selectmen of that town, appeared to answer Henry’s complaint that they were “not Supporting him in the work of the Ministry there”—a sadly familiar complaint of ministers in the poorer towns of northern New England. The court, which was not always sympathetic to Henry’s troubles, ordered the selectmen to assess “in due proportion” the town’s ratable polls and estates, guarding the interest of those who had already paid their share and make up the sum of twenty pounds that constituted Mr. Henry’s salary since June 1724. In making their order the justices recognized that Scarborough had been through hard times, reduced to “very low Circumstances” since “the late distroying warr.” For reasons not apparent the justices were less agreeable to another complaint that Hugh Henry had entered with them in April; he had at that time accused Selectman Libby of non-attendance at public worship. This court acquitted Libby—though they did tax him with substantial costs of court.

Samuel Smith, the Biddeford constable, then appeared to be admonished for neglect of duty in not making return on a warrant for bringing in his fellow townsman John Stackpole to the April court. He had apparently made good at last, however, for Stackpole himself next came forward to answer his presentment “for breaking the peace in Striking.” He was convicted and sentenced to pay a fine of five shillings and costs of twenty-five shillings. Smith and Stackpole were followed by another delinquent constable, Nathaniel Fernald of Kittery, and his prisoner, John Woodman of the same town. Fernald too was admonished, and paid ten shillings three pence in costs; Woodman, “for being drunk,” was fined five shillings to be used for the poor of Kittery, and fourteen shillings for fees of court. Two grand jurors who had failed to appear in April were next brought up; apparently their unrecorded excuses were good, for they were both acquitted.

The Court of General Sessions of the Peace had a general competence to oversee nearly every aspect of local government. That authority was exercised by and through the judicial process, and the next piece of business illustrates this aspect of the justices’ work. In April the town of Kittery had been found delinquent in not having “Standards”—that is, a set of officially approved scales, weights, and measures as required by law.1029 Now came forward John Dennett and John Thompson, selectmen of Kittery, to answer their town’s presentment. They were ordered “to take Effectual care” that the town obtain the required standards.

There was perhaps a stir, and maybe some laughter, as the clerk next called up John Woodbridge to face the charge of “striking” John Smith. Samuel Came had bound him over, as we have seen; the papers in the case were now read, or at least summarized. Woodbridge’s neighbor, John Adams, was surety for the innkeeper’s appearance “this day . . . before the Justices of the Court of Gen’l Sessions of the Peace”; perhaps he stood with Woodbridge as the latter faced the court. Jonathan Johnson and William Rowse testified, swearing that their written “evidences” were true; and Woodbridge was fined the usual five shillings to the King; then he must have gone back to keep a watchful eye on those provisions that he had stocked for the entertainment of the court and the onlookers.

The next case came to nothing, but it is not uninteresting to the observer two centuries later and probably evoked some talk at the time. In April Captain Elisha Plaisted of Berwick had lodged a formal complaint against one James Turner, also of Berwick, before Justice Hammond. Plaisted was a member of the Piscataqua “establishment.” John Wheelwright was his father-in-law, and his father and uncle had been prominent figures in both official and business circles in New Hampshire and Maine. Plaisted’s accusation was that Turner had stolen an iron canting dog from him; the tool had been “lying at the door” of Plaisted’s garrison house when Turner was alleged to have taken it. One witness, who testified at Hammond’s hearing of the charge in early May, had been told that Turner had “offered it at the Tavern for Strong drink.” But there were complications; other evidence hinted at an argument about the “dogg” between Plaisted and a Captain Oliver, who was commanding a detachment of soldiers in Berwick. Others besides Turner were also implicated, for Margaret Frost had said that “Edw’d Steward Offered to pawn an Iron Dogg for 20s” on 21 April; Turner, Michael Kelley, and Joseph Cross were in the house at the same time, and she heard Stewart and Cross say that “they would Stand by One Another in the Affair of the Dogg.” Turner had refused bail in May, had been committed, and it is possible, though not at all certain, that he had thus spent two months in jail awaiting his appearance at the court in July. But the court ordered an acquittal, “no Evidence Appearing to Convict him.” Acquittal did not free the accused of all obligations, however; the justices slapped a very heavy bill of costs on poor Turner. He was ordered to pay fees of court in the amount of £5:1:0.

In spite of that, James Turner went back to celebrate, perhaps. Equally fortunate was John Smith, the fisherman, who, still nursing a bruised head, now came forward to stand trial on the charge of uttering a counterfeit fifteen-shilling bill. Smith had been bound over by William Pepperrell, Jr., after what must have been a rather fascinating hearing in early May; at that time the offensive note was traced in a sequence of transactions back to Smith. A Portsmouth tavern keeper, Thomas Harvey, had spotted the counterfeit bill when it was offered him by John Neal; the latter said he had received it from Benjamin Lord, and Lord, in turn, traced it to one John Hooper. It was Hooper who implicated Smith. At the initial investigation, Smith, appearing before William Pepperrell, had refused “to make oath who he received sd bill of.”

All of this was doubtless retold before the assembly in Woodbridge’s tavern on that July day two months later, as Smith stood before the court. Then came the denouement; it may well have caused a mild sensation. John Smith, in court, “made Oath that the above sd fifteen Shilling bill w’ch he paid Jno Hupper he Receiv’d of Cap’tn Peter Nowel of York.” Nowel was a respected member of the community, a builder, militia officer, and grand juror, and in July 1725 a selectman; he was just a few rungs down from the top of the social ladder. Why, or how, he had obtained the counterfeit bill, never came out; nor was any charge ever laid against him in the matter.

Things were warming up, and the onlookers were perhaps beginning to feel that court week was not disappointing their expectations. There was perhaps some talk—certainly there had been some earlier—when James McCartney of Kittery stepped up to be cleared of his bond. In June McCartney had been placed under obligation, in five pounds, with two sureties, to be of good behavior until this July court; Colonel Pepperrell had found him guilty of “making & publishing a false & Scandalous report of John Woodman.” The latter, McCartney had said, “was a murdering old roge”; he had murdered two wives, and “ . . . he was a wizard & had bewitcht Several people. . . .” How fully these lurid charges were repeated in July, we cannot know, but most of those in attendance must certainly have heard them.

The flow of business went on. The selectmen of York answered satisfactorily a presentment for “deficient high ways”; John Burrill was fined for “profain swearing”; and John Smith stepped forward once again, this time to face the music for his “Reveling & disorderly Carriage” of the night before; perhaps Woodbridge had lodged a formal complaint against him. It had been a busy day and night for Smith, all in all. On this charge he was convicted and fined the usual five shillings for breach of the peace.

The court, spurred on by Justice Hammond perhaps, next ordered the clerk once more to issue process for summoning Captain John Heard of Kittery to appear at the October Sessions. Heard had been stalling for three years. In July 1722 he had been convicted of abusive behavior on Hammond’s complaint; he had stubbornly refused to pay the fine imposed then, and the court now rather testily said he must appear in October “to give his reason if any he have why he don’t pay the fine & fees of Court. . . .” Nearly everyone present must have known that Heard’s original conviction had stemmed from an unseemly altercation in the course of which he had repeatedly called Hammond “son of a whore.”1030

Another absentee who had long defied authority was the object of the next order of the court. Daniel Grant was in constant trouble on the matter of attendance at public worship. He was perhaps an unbeliever, possibly a Quaker; certainly his record was one of consistent refusal to attend public worship in Berwick, where he resided. Now the justices ordered process for his appearance at the next sessions to answer for his breaking away from the constable, who had sought to enforce Grant’s obedience to a sentence imposed in January 1723/24, more than a year earlier.

This court did not ordinarily concern itself with matters involving death; its jurisdiction did not, in practice, embrace capital crimes, nor did Quarter Sessions have competence in probate business. But it was the court to which the coroner reported, and the next entry on the docket reflects this. The entry also tells us, inferentially, of the dangers of that season and points up the fact that not all military casualties of the frontier stemmed directly from enemy action. In the winter of 1724–1725 William Welch was a soldier in Captain Jordan’s company at Winter Harbor (Saco). In April he had overturned and drowned as he proceeded upriver in a canoe; his body was not recovered for five or six weeks, for the inquest was held on 3 June, when he was “Taken up Dead & Brought in to York.” Now the coroner, Joseph Curtis, presented his record of the inquest post mortem and requested payment of three pounds, seventeen shillings. That sum represented what was still due, after Welch’s back wages of one pound, ten shillings, and four pence had been paid by the Province Treasury.

Another request for payment followed, from Benjamin Stone, who presented his account “for ringing the bell & fitting a plattform for the Superior Court,” which had convened in York the preceding May. Stone was paid twenty-seven shillings “In full discharge” of the account.

The county faced a more difficult and awkward problem as a result of the next matter to come before the justices. John Leighton, Joseph Hammond’s half brother, had served as High Sheriff from 1715 until his death in 1724. Now the committee which had been named to examine his accounts reported “that there is due to his Maj’ty £12:14:0 which [Leighton] received for fines more than he paid.” Leighton’s successor, Jeremiah Moulton, was ordered to demand the amount due from Leighton’s estate; the committee, William Pepperrell, Jr., and Samuel Came, were to receive eight shillings apiece for their trouble.

The July court was always an especially busy one, where such administrative orders were concerned. At least the clerk’s records showed more business of that kind then, for it was also in July that the justices granted annual licenses for tavern keepers and retailers of liquor and levied an assessment on the several towns for the county’s share of the Province tax. On this July day in 1725 the justices granted twenty-five licenses of one kind or the other, and in addition gave their host, John Woodbridge, leave to sell until the October court, he “having a Stock of drink by him.” Because the clerk always listed licensees by their town of residence, the social historian can readily identify the number of lawful taverns and retailers of drink for county and township. There was, too, an interesting sociology of taverns in colonial Maine. Tavern keepers in the more settled towns were frequently quite respectable widows; at the time, for example, Mary Preble kept a public house in York Village. She was the relict of Abraham Preble, formerly a justice of the peace and a judge of the Inferior Court, County Treasurer, and a man active in civic, religious, and military affairs; on his gravestone in York Village, he is styled “Captain of the Town.” Also employers were often licensed to retail liquor “out of doors.” The Pepperrells usually exercised this right, and so did Elisha Plaisted, who was heir to an extensive lumbering business in Berwick and the Salmon Falls region. In the more remote outposts, places like Falmouth, Richmond, or Arrowsic, it was usually the leading man of the place who conducted tavern business. So at this court Major Samuel Moody was licensed to retail in Falmouth, and John Penhallow was as usual given authority to sell liquor and operate a tavern at Arrowsic.

The Court of General Sessions of the Peace also had as one of its most responsible administrative functions the allotment of the Province tax among the towns, and the justices turned now to that business. It is more than likely that Daniel Simpson, the County Treasurer, had done his homework before this; the allotment of the county’s share of the Province tax involved a scrutiny of polls and estates and a pro-rated assessment of the total levy against each community, based upon the town assessments. So, now, the justices ordered an assessment against Kittery, York, Berwick, and Wells in amounts that give the historian a rough guide to the respective wealth of those towns; the total, set by the General Court, was one hundred pounds, half of which was payable on 1 October next following, and half on the first day of April 1726. It is to be noted that the newly settled towns east of Wells were not yet assessed. They had barely emerged as organized communities after nearly thirty years of war, and the 1720’s had seen, of course, a recurrence of hostilities. By 1726 things were better, for Falmouth, Biddeford, and Arundel appeared in the assessment, though for very small amounts.

If the clerk’s record accurately mirrors the sequence of events, the grand jurors may have been preparing their presentments while the justices considered the matter of liquor and tavern licenses; in the court book the list of presentments comes between the record of grants of licenses and the allotment of the Province tax. When Jonathan Bane of York, the foreman, stood up to hand in his report, the list of delinquents that he presented was perhaps a bit shorter than usual, though it was representative enough of the shortcomings of this colonial society: three presentments for “profain Cursing,” three for fornication, and one—that of John Jordan of Kittery, “Shipwright”—for neglecting the public worship of God on the Lord’s day.

It may have been the clerk’s afterthought, or a prompting from Justice Hammond, who had originally dealt with the matter, that led to the next piece of business. In January Peter “Wittum” (Witham) and his wife of Kittery had been presented for neglecting public worship. Perhaps, like the Grants of Berwick, they were dissenters from orthodoxy, because no fewer than eight Withams had originally been accused. Peter and his wife were convicted and sentenced at the April court, but three months later she had not yet taken her punishment. Now the court ordered a warrant of distress against “Peter Withum Jun’r his wife” for the fine and accumulated costs; in default of payment of the fine she was to be placed in the stocks for an hour. On the reverse of the warrant is the endorsement of Nathaniel Fernald, the Kittery constable, dated the next 4 October, that he had “put the wife of Peter Withom Juner in the Stocks the full Speace of one oure” and had collected the court fees of eleven shillings.

Assuming that the court book actually reflects the true order of events, the three most complicated cases came up at the end. The grand jurors had done their work and had been dismissed. The court had disposed of the county business, which was its responsibility to direct. Now the justices took on three matters which, it may be supposed, were the most complex and sensitive cases of those they were to face. An examination of the records will suggest why this was so. The first two of these cases stemmed from the same episode: they emanated from charges lodged against Daniel Morrison and Malachi Edwards of Wells, who were participants in a serious disruption of a special town meeting the preceding May; both men were presented for flagrant defiance of authority. The particular issue at the town meeting seems to have involved the potentially explosive question of a contested vote on the ministry; and the charge of defiant behavior against Edwards was the more serious because he was at the time one of the town’s constables. The third of these cases was also sensitive, for the defendants, seven residents of Kittery, had been accused of voting in the March town meeting, though not qualified.

Although Morrison and Edwards were tried separately, it is appropriate to look at the episode as a whole, for the accusations against them and the papers in the two cases give a single picture of the events which led to their troubles. The details of that turbulent affair were doubtless rehearsed before the company in Woodbridge’s tavern; how, before the formal opening of Wells town meeting on 5 May, Morrison was the leader of “a Confused tumult or disorder” in which many people were trying to talk at once; how Morrison called out in a loud voice, “We will have our Vote for our Minister in Spite of you all”; how, when Justice Joseph Hill ordered Constable Edwards to keep order and take Morrison into custody, Edwards refused to obey; how, when John Wheelwright thereupon ordered him to remove Morrison and confine him, “Malachy” went up to Justice Hill “in a Contemptious Manner,” pulled him by the sleeve of his coat and commanded him “in his Maj’t’s name to go and Stand guard over Morrison.” We cannot recover all of the details of this crisis, nor have anything more than a surface feeling for the animosities that rent the town of Wells in the spring of 1725. What sentiments were stirred when Morrison and Edwards came into court in July, we cannot know. It is perhaps safe to say, however, that the bench felt the powerful emotions of pride and outrage; and that some, at least, of the spectators warmed to the plight of the two accused men. The court records of these years reflect more than once a pervasive “we-they” divisiveness of feeling.

Perhaps Justices Wheelwright and Hill did not take part in the trials; the York magistrates of these years seem to have been generally scrupulous—or perhaps cautious—about sitting in cases where they were interested parties. But if so, their brethren upheld the honor of the court. Morrison was fined ten shillings and ordered to give bonds for his good behavior. Edwards, whose offense was clearly more serious in the eyes of the court, was fined the considerable sum of ten pounds and was also bound to his good behavior in the amount of fifty pounds.

Before that result was reached, however, some important procedural moves had taken place. A belief that popular feeling was with them prompted Edwards, at least, to ask for a jury. This was denied. Was it perhaps because in the justices’ view the two cases were seen as contempt of authority and, therefore, properly dealt with in a more summary fashion?

In addition, Edwards, and possibly Morrison, was almost certainly represented by counsel in the person of Benjamin Gambling, the Portsmouth attorney. It was Gambling who later drew up Edwards’s reasons of appeal, and that document reveals a full awareness of the trial proceedings in the case. The prosecution was likewise in the hands of an advocate, for the bill of costs lists a chargeable expenditure of ten shillings to the “Kings Attorney.”1031 In short, these two cases appear to have gone to trial in a real sense; so also did the case of the Kittery voters.

That issue, too, was a lively product of political tendencies fostered by the institution of the New England town meeting. More particularly, the case at bar had come about when, at the Kittery town meeting on the preceding 22 March, ten residents of that place “did presume to vote in the sd meeting,” though, it was alleged, they were not qualified by law. A reading of the record of the April court reveals that this was directly related to, or a cause of, bad blood between the Hammonds and their Frost kinsmen. The accused men had been “encouraged” to vote by Charles Frost, and Joseph Hammond had bound Frost over to the April court to answer that charge. Twenty-three of the defendants’ more affluent fellow townsmen had presented a formal petition to the April Court of Sessions, challenging their pretensions to the franchise. At that time the justices had committed the papers in the case to the grand jury, who, after careful study and deliberation, had returned presentments against seven of the accused men. It is the most fully documented political case to be found in the Maine records of the period from 1700 to 1727. The papers include: the complaint; a full list of all those who voted; reports of the constables, who were charged with collecting rates; a number of interesting depositions brought in to show the true value of the estates of the challenged men; and the bills of costs.

Now in July the cause came on for trial. The accused men put themselves on trial by a jury “Specially appointed & Sworn for that purpose.” The result was hardly calculated to give satisfaction or certainty. The jury returned a special verdict; the seven challenged men were found not guilty, “Except there be a Law that requires as voters Quallified to bring Evidence to the Town Meeting that he is Quallified.” There was no law that actually said a voter must “bring Evidence” to town meetings of his right to vote; there was, of course, an authenticated list of those who were qualified, drawn up by the town’s selectmen in their capacity as assessors. The accused men had been challenging this official list. The court’s judgment was that,

inasmuch as it appears by the List of rates [i.e., the official list] they were not Quallified at that time by the Law directing the Quallification of voters in town affairs, & were So found by the grand jury upon their Oaths, Its Considered by the Court that they be Admonished to conform themselves Accordingly for the future. . . .

The defendants were ordered to pay costs of court of £3:17:0.

I think we can assume that these last three cases, which were clearly of some importance and were, additionally, highly sensitive, were taken up after all the lesser matters and administrative decisions had cleared the docket. Probably, as in most complex and serious matters, no one quite knew how long the proceedings against Morrison, Edwards, and the seven Kittery voters might take. More to the point, perhaps, counsel required time to prepare argument and marshal facts, for, as in the cases against Edwards and probably Morrison, so in the Kittery voters’ case a defense attorney, Thomas Phipps, appears and doubtless someone representing the Kittery selectmen argued for the town, though the record is silent as to his identity.

It is not stretching fact to believe that these three “big” cases may have carried the court into the afternoon. The business of the Court of Sessions did not go over to Wednesday, however, for the depositions taken in the case of the voters bear the clerk’s endorsement “Sworn in Court, July 6, 1725.”

Well before sundown, then, the business of the Court of General Sessions of the Peace for the county of York was probably concluded. A few of those who had been fined or assessed costs of court might well have spent that night in the new prison that stood on a knoll opposite the meetinghouse and above the burial ground. Some who had no more business in York might already have gone home, but perhaps most of those who came in for court week stayed on. For the business of the Inferior Court of Common Pleas was still to be done and early the next morning, or even that afternoon, the civil side of the county’s judicial business would have its own day in court.

There was, indeed, a postscript to this Quarter Sessions. Daniel Morrison, Malachi Edwards, and the seven Kittery voters all appealed their convictions to the next Superior Court of Judicature, Court of Assize and General Gaol Delivery. Morrison and Edwards were successful; in their cases the judges of the Superior Court reversed the judgments of the York Court of Sessions. The case of the Kittery voters ended, not with an appellate bang, but in a post-trial whimper. They, or Thomas Phipps, their attorney, must have had second thoughts. They paid in their costs of £3:20:0 to Sheriff Moulton and put in no appearance on the appeal.

But all of that took place almost a year later, in May 1726. By the evening of 6 July 1725 the participants of the day’s events had retired from the field, each perhaps to find solace or celebrate a victory in his own way. Though doubtless for many rum was again the chosen medium, the records are silent as to any consequences. Perhaps even John Smith and John Woodbridge clinked a can together; at any rate, we hear no more—for this court, at least—of “Reveling and disorderly Carriage.”

Vernon Parrington wrote that “[t]he undistinguished years of the early and middle eighteenth century, rude and drab in their insularity, were the creative spring-time of democratic America. . . .”1032

Perhaps this account of a court day in the shire town of the old county of York gives some meaning to the statement. Not all the participants of events on that day would have found appealing the idea of a future American democracy. But all shared in a legal tradition whose roots went deep. Unruly and “rude” they often appear in these records, but the institutional framework and the inherited traditions gave force and meaning to the idea that law ruled. “Let him be what he will, he ought to have Justice done him,” wrote Joseph Hammond in 1708. And in April 1702 Joan Crafts, a widow who kept the tavern at Kittery Point, responded to a summons for her appearance, “For I desir as I live onder the Law to be guided by the Law. . . .”1033