John Clark, Esq., Justice of the Peace, 1667–1728

For us in America, even more than in England itself, the courts of common law have become the guardians of constitutionalism. Its source, far more than we have realized, may be found in another kind of court—the courts of neighbors, the “little commonwealths,” which preserved an ancient experience that most Englishmen had shared.

John P. Dawson419

THE Boston Weekly News-Letter for the week ending 12 December 1728 reported:

On Thursday Night of the 5th of this instant December, died here after long indisposition the Honorable John Clark Esq. about 61 Years old; he was made a Justice of Peace June 7, 1700, sometime since was Elected One of His Majesties Council of this Province and is to be interred on Saturday next the 14th.420

Apart from his will,421 which was proved before Samuel Sewall on 23 December 1728, very little remains of the record of the life of John Clark. The will is suitably, but not emphatically, pious. The estate’s account, submitted on 3 May 1731, discloses property worth well over £6000, including a large number of modest debts owed Clark.

There are a few other facts to be gleaned from surviving records. Clark graduated from Harvard in 1687; his senior oration was entitled, “An Morborum Sedes Sit Anima Sensitiva.”422 Both his grandfather and father were physicians, an occupation which John Clark, Esq., also followed, although the extent of his medical activities is unclear. In his will he left to his son John “all my Instruments and utensills of surgery.” Samuel Sewall, a prominent figure in Massachusetts legal affairs, reported in his diary that on 23 January 1718/19 Dr. Clark came to treat his daughter Hannah’s swollen ankle.423 Hannah recovered six months later.424

John Clark’s life was very much like, and yet contrasts with, that of a close contemporary, Cotton Mather. Mather lived from 1663 until 23 February 1727/8, almost exactly the same lifespan as John Clark. They both resided in the north end of Boston, and John Clark belonged to Cotton Mather’s church, the North Meetinghouse. Mather mentioned Clark in his diary occasionally. He was identified as being on several special committees having to do with repairing the meetinghouse.425 Sewall, by contrast, recounted numerous meetings with Clark on ceremonial occasions and referred to Clark at death as his “beloved Physician.”426

The major element of contrast, evident in the Journal of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts,427 is that as Mather’s political power receded, Clark’s grew, along with that of the group of people with whom he was identified politically, primarily the Elisha Cookes, father and later son. David Levin has argued that Cotton Mather lost his power because of the witchcraft episode and his family’s identification with the Charter of 1691, which Increase Mather obtained from King William.428 Clark apparently joined what has been called the “popular party”429 in the House, a loose grouping of representatives characterized by opposition to the royal governors under the Charter of 1691 in general, and opposition to provincial taxation in particular.

Once Clark’s rise to political prominence was achieved, it continued nearly to the end of his life. He was named a justice of the peace on 7 June 1700.430 First elected representative to the General Court from Boston in 1708,431 he served until he was elected to the Governor’s Council by the General Court in May 1715.432 He remained on the Council until the Royal Governor, Samuel Shute, rejected his re-selection in 1720.433 Clark was promptly returned as a member for Boston and immediately elected Speaker,434 being reelected in 1721,435 1722,436 and 1723.437 Elisha Cooke, the son, replaced Clark temporarily in 1722 on account of Clark having an “indisposition.”438 He was re-elected to the Council and accepted by the Governor in 1724,439 serving there until his final illness.440

Clark’s political position in the ongoing fights between the Governor and the House of Representatives of this period is shown by the Journal report of Clark’s election as Speaker after Shute’s rejection of him as a councillor:

A Message from his Excellency by Mr. Secretary, in the words following, Viz I Accept the Choice of John Clarke Esqr as Speaker of the House of Representatives.

August 23d 1721 Samuel Shute Ordered That the said Message be Returned by Mr. John Fortes, and that he inform his Excellency, that this House, when they sent up to Acquaint his Excellency, and the Honorable Board [Council], with the Choice of a Speaker, they did it for Information only, and not Approbation.441

Not surprisingly, the first Amendment to the Second Charter, included in King George’s Explanatory Charter of 1726, provided that a Speaker chosen by the General Court must be presented to the Governor “for his Approbation.”442

There are other bits of evidence which demonstrate Clark’s adherence to the “popular party.” Clark and Cooke were frequently elected together and Cooke succeeded Clark as Speaker. Clark is identified as being a member of the numerous committees appointed by the General Court to audit the province’s financial affairs, including the validity of muster rolls.443 His service on these committees occurred at a time of constant, but not savage, conflict between the General Court and the royal governors over financial affairs. In his years as Speaker, Clark had to speak officially for the General Court on such matters. In a letter to Governor Shute, dated 1 September 1721, he defended the House vigorously, but not disrespectfully, for adjourning in a prior session without the Governor’s permission.444 The second Amendment included in King George’s Explanatory Charter decreed that the General Court could not adjourn itself for more than two consecutive days “without leave from the Governor.”445

These facts and the will were all we previously knew about John Clark. But, by great good fortune, it has recently been discovered that Clark also left a 269-page judicial book, still in private hands, which contains 1,379 entries describing his actions as a justice of the peace from July 1700 until December 1726. The book may be akin to an official record, for it does not contain a single personal comment or reference. The litigants’ names are listed first; the dispute described; the disposition entered; moneys received are noted; and occasionally the legal issue applied in a case is adumbrated. The book appears to have been kept chronologically and contemporaneously; only an occasional entry is out of order.446 Later notations are made on earlier entries in the event of the issuance of a writ of execution, but such notations are separately dated.447

After spending considerable time with a book such as Clark’s, one is tempted to overrate its importance. As a record describing the activities of a busy justice of the peace in the fairly stable, legally speaking, period of the second charter, it is unique. It permits some evaluation of social developments in Massachusetts in the provincial period. Finally, it is a document which allows one to assess, probably as well as any eighteenth-century legal materials, the performance of a true lay judge. Clark was a physician, a commercial figure, the owner of several parcels of real estate, and, as just described, a politician of some eminence. He was not a lawyer, and there is no evidence that he had any legal training or access to any legal materials, such as a copy of Lambard’s Eirenarcha: or of the Office of the Justice of Peace or Dalton’s The Countrey Justice.448

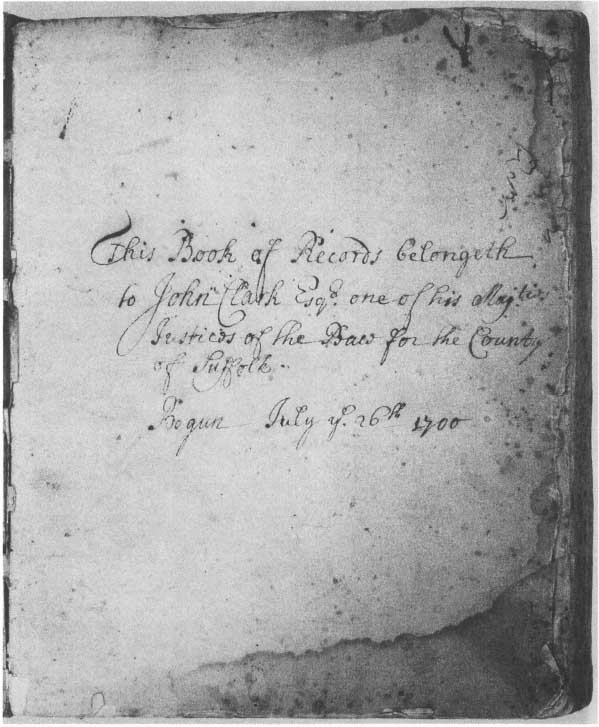

10. Title Page, Book of Records belonging to John Clark (1667–1728), Justice of the Peace, Suffolk. Courtesy, Collection of James A. Henderson, Jr.

A. A Justice of the Peace

Those who have read the judicial book449 of the various Pynchon family judges will easily grasp the main difference between it and Clark’s book. Clark’s book is a formal, tightly controlled record of the proceedings before him. It may be that the organization, discipline, consistent format, and flavor of doctrinal stability found in the Clark book are attributable to the author. It seems more likely, however, that these characteristics are due to the fact that a justice of the peace in Boston around 1700 was dealing with fewer legal uncertainties than the Pynchons. In addition, Clark did not have to establish the credibility of his judicial office in a quasi-frontier context. Thus, unfortunately, Clark was less likely to be as fully descriptive as the Pynchons in recording various matters.

Justices of the peace, like John Clark, were selected by the royal governor. Although there is no direct evidence on Clark’s appointment, the Governor presumably acted on the advice of his council in judicial appointment matters, as provided in the Charter.450 The oath required of a justice of the peace was established by statute451 and followed closely the oath current in England at that time.452

The large number of matters handled by John Clark, particularly in the years 1710 to 1720, in relation to the Boston population which Carl Bridenbaugh has estimated at 9,000 in 1710 and 12,000 in 1720,453 raises the question of the number of justices in Boston and their level of activity. The Boston selectmen’s records provide some evidence on this matter. The selectmen met frequently with the justices and occasionally with the justices and the overseers of the poor. The three groups jointly appointed deputies to perform certain extra-judicial functions. In this period the number of justices who met with the selectmen averaged ten.454 The core of this group in the early years included Clark, Elisha Cooke, Sr., Jeremiah Dummer, Elisha Hutchinson, Edward Bromfield, Penn Townsend, and Isaac Addington.455 Judging from the records of joint meetings of the justices, selectmen, and overseers, there must have been sixteen or seventeen justices actually holding office.456 It is not possible to estimate how many of this number were active.

Being a justice of the peace may not have been the road to wealth in colonial Boston, but the fact that it did produce income can not be ignored. A justice of the peace seems to have derived income primarily from his issuance of “process-type” papers. Chapter 18 of the Province Laws, passed on 22 October 1694, provided that a justice should receive a fee of one shilling for issuing a writ in any case to be tried before a justice.457 John Clark’s book does not account for the receipt of such sums even though he was careful to show payments of fines. The notation of each fine received, at least early in the diary, was accompanied by a pointed reference to its belonging to King William.458

Chapter 21 of the Province Laws of 1700–1701 required a justice to account for and pay over all the King’s fines to the receiver-general of the province once every six months. The penalty for failure to file this account in a timely fashion was five pounds.459 The clerk of the peace, who performed such duties for the justices in session, was not responsible for the activities of a single justice.460 Thus justices of the peace may have appropriated to themselves extra income by failing to report receipt of fines or by holding such fines for periods before turning them over to the proper authorities. Since at his death the inventory of Clark’s estate showed a large number of small debts, it is reasonable to infer that he had a ready supply of cash which he was lending out. It is possible that the King’s fines provided some or all of that cash.

When finally paid, not all fines were awarded to the King. For instance, upon conviction of a single offense of profane cursing or swearing, an individual had to pay a fine of five shillings to the “poor of the town” or sit in the stocks.461 Clark regularly fined profaners for the benefit of the poor.462 People convicted of selling alcohol without a license were fined substantial sums, four pounds463 or six pounds,464 to be applied to “the use of the free school” in Boston and paid to the town treasurer. All fines due to a town or county for the use of the poor or whatever had to be reported and paid biannually.

Another source of revenue for a justice of the peace was his perforrnance of certain functions which were not likely to be recorded. Chapter 21 of the Province Laws of 1697 provided that a deed “be signed and sealed . . . and acknowledged . . . before a justice of the peace. . . .”465 The statute set no fee, but something was presumably paid for this accommodation. Few matters of this sort are included in Clark’s book. On 8 July 1701 Clark wrote, “Joseph Richards and Anna Carver both of Weymouth personally appearing before me John Clark one of his Majesty’s Justices of the Peace for the County of Suffolk producing a certificate of their publishment according to law were married.”466 Significantly no payment for performing the marriage is mentioned, supporting the view that the diary noted only receipt of sums due to the Crown or local governments.467 Also significantly, no other marriage was recorded in the remainder of the book.

It is probable that some of John Clark’s activities as a justice were uncompensated. For instance, he recorded on 21 March 1701 the swearing of Benjamin Frame of Boston as a constable.468 Justices performed numerous other such duties, discussed later in this paper, which revolved around their status as quasi-municipal officials and which were uncompensated. For instance, Chapter 6 of the Province Laws of 1692–1693469 sets no fee for the service of a justice in swearing a surveyor of highways. On the other hand, not all ancillary functions were unpaid. In 13 March 1704–1705 Clark ordered one John Tedman, who was found after a search pursuant to a warrant to have Peter Paity’s missing copper kettle, to pay “the Charge of [Paity’s] Warrant.”470

In sum, although the financial dimensions of being a justice of the peace are not completely clear, the position seems to have provided an opportunity for earning some income. Some income might have been direct and legal, like fees for services. Other income might have been attributable to “borrowing” or using fines due the Crown or local authorities until such time as they had to be accounted for.

B. Crime

The English justice of the peace was primarily associated with criminal justice. Books of authority contemporaneous with John Clark’s activities, such as W. Nelson’s Office and Authority of a Justice of Peace (1721), J. Shaw’s The Practical Justice of Peace (1728), or Dalton’s are mainly concerned with crime and what is labeled below as regulatory offenses.

John Clark’s book, by contrast, indicates that his activities were largely civil. In his twenty-six years as justice of the peace, he reported 264 criminal matters and 455 civil matters.471 There were also fifty-six prosecutions noted of “special” ordinances of a local character in the third category of “regulatory” offenses.

Even though Clark’s activities involved primarily civil matters, his criminal jurisdiction was nonetheless important. As a justice of the peace, Clark tried and decided the merits of four major classes of offenses: (i) theft and receipt of stolen goods, (ii) breach of the peace, (iii) speaking profanely, and (iv) libel or false reporting. In addition, he handled four other classes of offenders in his capacity as an officer empowered to grant recognizances: (i) sexual offenders, including fornication and bastardy, (ii) suspicious or threatening individuals, (iii) Sabbath breakers and other blasphemers, and (iv) people indicted by the Suffolk County grand jury.

Theft accounted for approximately one-tenth of Clark’s criminal business. As a single justice of the peace, he was authorized to decide a theft if the “damage” caused did not exceed forty shillings.472 Damage, as applied by Clark, meant the value of the goods purloined. As punishment for a theft, John Clark invariably ordered that the defendant pay to the victim three times the value of the goods stolen.473 He would give a credit of up to one-third of this amount if the stolen property was returned.474 Colonial law appears to have permitted a justice to impose on a thief a fine for the Crown in addition to the trebling. John Clark fined thieves five to fifteen shillings,475 and if they were unable to pay the fine, they were whipped. The book noted receipt of the Crown’s fine in almost every case, but does not account for the payment to the victim.

Peace offenses comprised over half of Clark’s criminal jurisdiction. The range was large, from “rioting” to family quarrels, with one-on-one assaults being the norm. One of the more serious “peace” cases in the book476 involved a riot and fight among four lodgers at Atkeson’s house in the north end of Boston at two in the morning. Clark and another justice, Jeremiah Duncan, fined the rioters five shillings each and required them to make recognizances for future good behavior.

Various punishments were available in peace cases,477 including fines, the stocks, whipping, or placing the wrongdoer in a cage. Fines predominated, and of the alternatives whipping was used the most, particularly where Clark appeared to doubt the defendant’s ability to pay a fine. One case involved a punishment for a battery committed by Timon, a black servant to Mr. Samuel Dummer.478

A modest proportion of the peace offenses was related to drunkenness, technically a separate crime from breach of the peace.479 Historians of the criminal law have found it difficult to distinguish these crimes. Thus, although Clark occasionally dealt with drunkenness offenses,480 one cannot confidently separate these few instances from the general category of peace offenses.

Convictions for profane cursing or swearing constituted the second largest number of criminal matters, 79 out of 264. Chapter 18 of the Province Laws of 1692–1693,481 as amended by Chapter 9 of 1693,482 authorized a five-shilling fine for the first swear or curse and twelve pence for every additional profanity spoken on the same occasion, all fines to be applied for the relief of the poor. If a profaner could not pay the fine, the stocks and lash were available. A profaner could be convicted by his own confession, the testimony of a single justice of the peace, or the testimony of two other witnesses. If a profanation offense was not reported within thirty days, it was not actionable. One of the early entries in the book is typical of profanity matters:

Sept. 7 [1701] William Cavet resident in Boston Mariner convicted before me John Clark Justice of the Peace of prophane cursing and swearing five times. Ordered to pay nine shillings as a fine to the use of the poor of the town of Boston or to set in the stocks two hours received 9s.483

This entry shows that Clark adhered to the rules on the fines, but it does not reveal by which evidentiary method Cavet was convicted. The “before me” referred to the conviction, not hearing the actual profanation. Clark’s failure to describe the method of proof contrasts with his care in reciting the basis of proof in a civil debt and contract matter, to be discussed later, in which a defendant failed to appear.

Knowledge of the incidence of profanation offenses in Massachusetts in the period of turbulent economic growth from 1700 to 1730 would be very interesting to a social historian. One might expect concern with such matters to diminish during the period of Clark’s book. Unfortunately, no sure conclusion based on the book alone is possible. Since the book trails off beginning in 1721, as Clark’s political and other activities took perhaps more of his time, it would be impossible even to guess about the frequency of profanation prosecutions. There is always the possibility that Clark might personally have held a particular position on the crime itself, favoring or disfavoring it by his issuance of process papers. In spite of these caveats, the book does give the reader the impression that profanity was receding as a social concern.

Section 7 of Chapter 18 of the Province Laws of 1692–1693 made it a crime for “any person . . . of the age of discretion ( . . . fourteen years or upwards) wittingly and willingly [to] make or publish any lye or libel, tending to the defamation or damage of any particular person . . . , [or] make or spread any false news or reports with intent to abuse and deceive others.”484 John Clark heard a number of defamation matters. If convicted, an offender was fined five shillings and Clark also made him present “sureties for good behaviour”485 until he appeared at the next general sessions of the peace.

One sensitive libel case486 shows that Clark would occasionally act without explicit authority. On 30 August 1706 Clark had James Robes and Jonathan Woodman before him for “publishing a base, abusive and scandalous lying report concerning his Excellency Joseph Dudley, Esq.” Dudley was an unpopular governor. Clark did not hear the merits of the case but required the defendants to find sureties and be recognized in the startling sum of £100. A libel action of this sort seems to have been within Clark’s statutory jurisdiction. It may be that “serious” matters, even if within a single justice’s jurisdiction, were sent to the general sessions of the peace.487

A Massachusetts justice of the peace was more than a trial judge for petty criminal and small civil actions. He handled the equivalent of bail hearings for individuals charged with crimes beyond his jurisdiction. Although technically within Clark’s jurisdiction, the case involving Governor Dudley, just mentioned, is an example. More often, a justice usually determined a bail equivalent on matters clearly placed by statute beyond his jurisdiction. Sexual crimes comprised the largest class of criminal cases in which John Clark had to obtain security for the appearance of an accused person in another court. Massachusetts law placed fornication and bastardy within the jurisdiction of the general sessions of the justices of the peace.488

A typical case489 involved Alice Cook of Needham, who confessed on 15 July 1712 to fornicating with Henry Dewin of Needham and that she “now goeth withall” pregnant by him. Clark ordered Alice to find sureties in the amount of four pounds to guarantee her appearance before the general sessions for the following October. He also issued a warrant for the apprehension of Henry Dewin. On 17 July Henry made his own recognizance490 before Clark, in the amount of five pounds to appear before the sessions and was ordered to “not depart [from Boston] without license.”

A second class of isolated recognizances, those not linked to appeals of matters previously decided by John Clark, involved people thought to be suspicious or threatening. Modern police practice is not as aggressive as that of colonial Massachusetts in this regard. On several occasions citizens brought before Clark individuals who, they alleged, had been threatening people. In each case Clark would require the accused to find sureties in a significant amount. For instance, on 24 July 1706 Joseph Callender, a Boston tailor, sought protection from Thomas Hunt, a Boston turner.491 Clark ordered Hunt to find a surety and be recognized in the amount of fifty pounds for his appearance at the next general sessions of the peace. Entries like this one were not annotated in any way that would reveal what happened at the general session.

The ability to bind over a defendant indefinitely and without a specific accusation was linked to a justice’s right to issue the ancient recognizance of the peace. The author of the 1705 edition of Dalton’s explained in twenty-three pages492 that the recognizance of the peace, existing by implication rather than express grant, lasted for the lifetime of the defendant and could be lifted only by the sessions with the consent of the victim or victims of the original offense.493 It was distinguishable from the various recognizances requiring an appearance to answer a charge in that it was equivalent to a suspended sentence or probation. Clark used the recognizance of the peace occasionally, as in the case of the four lodgers mentioned earlier.494

The third class of recognizances involved Sabbath breaking and other actions which bordered on blasphemy. Early on, Massachusetts made blasphemy a capital crime.495 The Privy Council disallowed a statute under the second charter which had maintained it as a capital offense.496 The disallowed statute was replaced in 1697 with one that made blasphemy punishable by six months imprisonment or various forms of torture or humiliation.497 Lesser crimes of this type also existed. For example, a person convicted of Sabbath breaking could be fined twenty shillings.498 A single justice of the peace could decide such cases. That only a few trials of these latter offenses were reported in Clark’s book,499 and all in the early 1700’s, suggest that minor religious offenses were not prosecuted in Boston during this period.

Finally, recognizances were imposed to guarantee appearances to answer various presentments by the grand jury. By far the largest number of grand jury presentments which led to recognitions before Clark involved the unlicensed selling of alcoholic beverages. These will be discussed in the next section as part of the regulatory responsibilities of the justice of the peace. Another significant group of presentments involved allegations of fairly serious religious deviance. John Green, a Boston schoolmaster, was brought before Clark and Samuel Sewall, another justice, to post security to appear and answer a charge of “composing and publishing a mock sermon full of monstrous prophaness and obscenity. . . .”500 Green was fined and required to recognize a surety in the sum of fifty pounds. He produced Ephraim Savage, identified as a “Gentleman” in Clark’s book, as his surety.

Sewall reported in his diary for 22 and 23 February 1711–12 that the case against Green had commenced when a Mr. Pemberton complained to him. Sewall went to “Dr. Clark’s” the next morning because “his house [was] amidst the people concerned.” Together Sewall and Clark “stop’d Green’s Lying mouth.”501 It is not clear whether there is any relation, but a month later the General Court passed a law which fixed as a punishment for “composing any filthy, obscene or prophane . . . mock-sermon, . . . a fine to her majesty not exceeding twenty pounds, or by standing in the pillory once, or oftener, with an inscription of his crime, in capital letters, affixed on his head. . . .”502

Although it is not possible to learn a great deal about the grand jury in Boston from the recognizances in Clark’s book, a few observations can be made. First, since Clark’s book shows thirty-five recognizances generated by grand jury presentments, it seems reasonable to conclude that the grand jury was active in Boston during this period. Second, the grand jury seems to have acted on noncapital matters only if they involved cases outside the jurisdiction of a single justice of the peace. Third, some matters, like fornication, which could be formally initiated by a summons, sometimes commenced with a presentment. There is no explanation why some commenced one way and others did not.503

This third description is illustrated by the case of Eliza Faulkner, a Boston widow, who was required on 23 June 1707 to make a recognizance and find a surety to answer before the general sessions “a presentment of the Grand Inquest for . . . the County of Suffolk for being guilty of uncleaness with Dr. Hewes at the House of the widow Midwinter of Boston.”504 On 16 July 1707 the widow, Provided Midwinter, also made a recognizance “to answer to a presentment of the grand inquest for . . . the county of Suffolk for keeping a bawdy house.”505 It is not surprising that these offenses went to the sessions, but it is hard to find any principle which separates Eliza Faulkner’s matter from the non-grand jury cases of fornication which Clark regularly bound over to the sessions without a presentment. It may be that Eliza Faulkner’s companion was married and that the more serious, but still non-capital,506 punishment for adultery required the grand jury’s attention.

To summarize, John Clark’s criminal business was about one-half the magnitude of his civil business. The majority of the crimes were theft and peace offenses, and the rest a mixture of religious and morality offenses. In addition to trials, Clark acted to secure the appearance of individuals charged with more significant crimes either upon a private complaint or a grand jury presentment.

As anyone familiar with modern criminal law will attest, the substantive criminal law is only one part of any system for identifying and punishing crime. A source of great modern concern has been pre-trial and trial procedure. Unfortunately we can glean very little about these matters from Clark’s book. One thing is clear; justices of the peace relied heavily on local constables to operate their courts. Clark fined two people for resisting a constable507 and two other people for refusing to cooperate with a constable.508 In only one case is the office of the sheriff mentioned;509 three sailors were fined ten shillings for “affronting the Deputy Sheriff in his attempts to secure” the peace. This heavy reliance on the constabulary perhaps explains the large number of people who declined election to that office, according to Boston’s records, during this period.510

Justices of the peace were authorized to grant warrants to search for stolen or illegally imported goods.511 There is no way to evaluate the basis on which warrants were issued; indeed, the use of a warrant is mentioned in only one of Clark’s cases.512 Peter Paity procured from Clark a warrant directing a constable to search for a copper kettle. Constable Gardner found the kettle in the shop of a brazier named John Tedman, who claimed his wife had recently purchased it. Clark gave Tedman’s wife the chance to produce her vendors. She apparently failed to do so, whereas Paity had witnesses who testified to his ownership of the kettle. Clark ordered Tedman to return the kettle and pay Paity the “charge of the warrant. . . .”

John Clark’s book provides more insight into the disposition of cases than pre-conviction procedure. One fact is startling by modern standards: every criminal case reported in the book ended in a conviction. Since Clark did report the occasional victory by a defendant in a civil matter, it is possible that the absence of findings of innocence may indicate that each person charged criminally was convicted. On the other hand, it may have been a record-keeping convention not to enter findings of innocence since there were no fines to be reported and thus they had no record-keeping significance.513

In the vast majority of cases the defendants were punished with fines. The size of the fines depended on the relevant statutes. Clark seems to have imposed fairly low fines, viewed from the allowable limit. This may help explain the startlingly low level of criminal appeals.

In the rare instance in which a defendant could not pay his fine, Clark would substitute, depending on the case, a whipping, a night in jail, or some other punishment of public humiliation. There are only two cases in the book in which Clark ordered a whipping without mentioning a fine; one involved an Indian defendant514 and the other a black.515 The case of John Tunagain is illustrative:

John Tunagain Indian convicted of drunkeness and prophane cursing three times the last night ordered to pay five shillings for cursing or to be whipt publicly ten stripes and to pay costs of prosecution. Standing committed till the sentence be performed.516

A number of convicted individuals were committed to jail pending payment of their fines, but in most cases John Clark’s book notes receipt of the fine assessed. “Costs” are occasionally assessed in criminal matters, as in the Tunagain case, but the elements and amount are not specified.

It has been noted that Clark tended to fine in the lower ranges of what the law permitted. On one occasion when Clark imposed the maximum fine, a case of selling liquor without a license, he wrote that it was Margaret Johnson’s “second conviction.”517 Apart from this one comment there is little information on what influenced Clark in sentencing. He treated seamen specially. For instance, he lifted the recognizance of the peace imposed on Thomas Lonyon, a mariner, “upon [his] going to sea.”518 In another case Lieutenant William Skye of a company of Marines was asked to guarantee the appearance of Thomas Turland, a seaman, “upon the return of the ship Saphire from her present cruise.”519

A. criminal defendant aggrieved by the decision of a single justice of the peace could appeal for a new trial to all the justices gathered at the general session.520 Only five people made recognizances to appeal from Clark’s criminal judgments.521 This is a small number of the over 260 criminal convictions during the period of the book, but probably not atypical.

The deeper social facts about the jurisdiction of a single justice of the peace are hard to learn from Clark’s book. Who was involved in Clark’s court and what was the geographic and sociological domain of his criminal litigants? As mentioned previously, Clark lived in the north end of Boston. If a Massachusetts justice of the peace of this period was a truly local figure, then one might suppose that Clark handled cases with a locus in the north end. There is some support for this in the book. All of the precise geographic locations within Boston mentioned in the book were near Clark’s home. Scarlet’s Wharf is mentioned in two cases;522 a riot occurred on Prince Street;523 two servants scuffled in the new North Meetinghouse one Sunday.524

Unfortunately the precise location of most crimes is not mentioned and all that can be confidently stated is that the defendants and victims were overwhelmingly from Boston.525 Thus the issue of how people came to Clark as a justice, whether because of geographic proximity or, as seems more likely, the result of a decision made at some point in the issuance or return of original process cannot be established from the book. The sharp decline in the number of cases during the last ten years of the book suggests that either Clark or the litigants could control the number of cases which he was to hear and that there was, within Boston, no rule requiring a litigant to use the nearest justice of the peace.

Somewhat more can be said about the social status of those who were involved in Clark’s criminal jurisdiction. In general, the book seems to support the notion that criminal defendants either had no profession or occupied what can easily be identified as lower status positions, like mariners or laborers.526 By contrast, and this will be discussed later, civil litigants seemed to be predominantly shopkeepers and small-business people.527

In addition to being overwhelmingly of low occupational status a number of criminal defendants were black; some were identified as freemen, most were referred to as servants, and one was called a “slave.” Most of the matters involving blacks were theft offenses and, as mentioned earlier, Clark’s punishments seemed harsh.528 In all cases involving blacks, the possibility of a whipping was noted, whereas with whites it was rarely mentioned. The record indicates at several points that the master or mistress of a black servant intervened to pay the fine or provide security for the servant’s good behavior.529

One of the well-known local policies from the earliest settlement of colonial Massachusetts was the prevention of idleness.530 Chapter 8 of the Province Laws of 1699–1700 gave to a single justice of the peace, or the general sessions, the right to commit persons to a county house of correction—a workhouse supervised by the justices:

all rogues, vagabonds and idle persons going about in any town or county begging or persons using any subtle craft, juggling or unlawful games or plays, or feigning themselves to have knowledge of physiognomy, palmestry, or pretending that they can tell destinies, fortunes or discover where lost or stolen goods may be found, common pipers, fidlers, runaways, stubborn servants or children, common drunkards, common nightwalkers, pilferers, wanton and lascivious persons, either in speech or behavior, common jailers or brawlers, such as neglect their callings, mispend what they earn, and do not provide for themselves or the support for their families.531

In one case John Clark committed Lucy, a black servant of a Mrs. Moor of Boston, to the house of correction for fortune telling.532 Her mistress made a recognizance sufficient to secure Lucy’s freedom until the next general sessions. In another case,533 John Endicott, identified as a Boston cooper, turned his black servant over to Clark for commitment to the house of correction because of ungovernability and stubbornness. The servant attempted to escape and Clark ordered that he be whipped. Apparently Endicott and his servant were reconciled, for three weeks later Endicott made a recognizance534 after appealing a new conviction of his servant for publishing a lie concerning Jonathan Wardell, a carpenter.

Blacks were occasionally identified as victims before Clark. In five cases535 Clark convicted a non-black of assaulting a black. One master, John Peak, a Boston sawyer, was required to make a forty-pound recognizance guaranteeing his appearance at the next general sessions to answer for “cruel treatment towards his Negroman Primus and that he shall carry it well toward his said Negro in the meanwhile.”536

The two largest racial minorities in Boston in 1700 were blacks and Indians. Only a few of Clark’s criminal cases involved Indians. They were mostly peace matters and one interesting theft case:

Dick an Indian man servant to Mrs. Leach convicted of stealing cabbages from Captain James Grant at the north end of Boston the cabbage being returned with which said Grant being satisfied. Ordered that the said Dick be whipt ten stripes at the public whipping post in Boston.537

This is the only entry in the book in which Clark mentioned that he meted out a punishment greater than what had been sought.

Beyond the foregoing, there is not much which can be confidently said about the status of the criminal litigants. There is one case538 in which a minor was the defendant. Occasionally white servants appeared and, as implied previously, virtually no matters involving people of high status. Family violence cases do stand out in the record, not because of their great number but because of the apparent severity of Clark’s punishments. John Allum, a currier, was required to make a recognizance with sureties in the amount of £100 for “beating and bruising his wife.”539 Job Bull was also required to make a £100 recognizance with sureties for having an altercation with his wife.540 George Burrel had to make a £20 recognizance for fighting with his wife,541 and Thomas Atkins made a recognizance for £30 for “abusing his mother-in-law.”542 It is unclear why Clark did not try to convict these defendants under the assault language in the breach of the peace statute.543 It may have been that these assaults were considered so serious that the probable punishment was beyond the power of a single justice, like Clark.

C. Regulatory Offenses

A Massachusetts justice of the peace was not just a judge. As a magistrate, he performed numerous executive functions. The records of Boston’s selectmen for the years of John Clark’s justiceship refer to numerous meetings among Boston’s justices of the peace in session and the selectmen. William E. Nelson has written that a county’s sessions court “was, in effect, the county government.”544 Frequent meetings were called to agree on how and when the justices, selectmen, and overseers of the poor would share the duty of taking nightly walks “to Supress disorders for the Space of Eight weeks. . . .”545

The records of the selectmen list the justices who attended and, as compared with Samuel Sewall and others, Clark came infrequently. Some of Clark’s appearances seem attributable to his position as a physician rather than his justiceship, but one cannot be sure. For instance, the selectmen asked that:

11. Entries, 7 May to 14 May 1711, Book of Records belonging to John Clark, Justice of the Peace, Suffolk. Courtesy, Collection of James A. Henderson, Jr.

John Clark, Esq. . . . goe on board his majesties Ship Seahorse and Report in what State of health or sickness the Ships Company are in, Especially with respect to Smal Pox or other Contagious Sickness.546

A later entry disclosed547 that the Seahorse was so badly infected with smallpox that outsiders had to pilot it down to Bird Island to put the risk of infection further from the city. At first glance this might appear to have been an occasion on which the selectmen were relying on Clark’s medical expertise. The General Court had attempted to give justices of the peace the power to fine sailors who disembarked from quarantined vessels not yet licensed by the health officials to land.548 The Privy Council rejected this statute on the ground that the royal governor could control this problem by rules.549 In any event it is not always easy to determine in what capacity the selectmen called upon a particular person who might be a justice of the peace.

The primary executive role of the justice was to act on, or participate in, the administration of various matters of a regulatory nature. For instance, the justices and selectmen agreed on 31 January 1723/4 that various of them, including John Clark, Esq., inspect within their assigned parts of town on 14 February “Disorderly Persons new Comers the Circomstances of the Poor and Education of their Children etc. and to meet at the hour of five of the Clock of the Evening . . . ,”550

These regular inspections involved the justices directly. They were less directly involved in the licensing of innholders to serve strong drink. The selectmen did this at least annually,551 and their records suggest that it was a function of some significance. Clark bound over all licensing offenders indicted by the grand jury, sixteen in the twenty-six years, to the general sessions. These represent the largest single classification of presentments handled by Clark. The level of the recognizance amount was typically low if compared to the criminal recognizances. The following case is illustrative:

Rebeccah Philpot recognized in the sum of five pounds on condition that she shall appear before her majesties Justices of the Peace at their next sessions by adjournment on the last Monday of this current August to answer to a presentment of the Grand Jury for selling drink by retail without license.552

Clark decided a number of liquor sales cases generated by informations553 rather than grand jury presentments. Statutes provided that conviction for unlicensed sale subjected a person to a fine by a single justice or the justices in session of forty shillings; one-half to go to an informer and the other half to the poor of the town.554 In cases of this sort, Clark would mention that an informer provided the information,555 as in the case of John Buttley. On 7 August 1710 Clark noted, “I paid the informer 40s,” which was one-half the fine he imposed.556 Richard Pullen “informed against himself,”557 perhaps hoping to reduce the fine, and Mary Smith appealed her conviction to the general sessions.558

Justices of the peace were supposed to work with local officials to ensure that a ready militia, composed of companies organized around individual officers, was maintained. Chapter 3 of the Province Laws of 1693–1694 established an elaborate system for raising the militia,559 giving a single justice the power to fine a person who failed to participate. John Clark fined one Henry Wright ten shillings, as provided in Chapter 3, for failing to appear for muster.560 Clark bound over to the general sessions an individual “impressed in her majesties name” into the company of Lieutenant-Colonel Adam Winthrop.561 Although Clark’s book contains relatively few entries of this type, the simultaneous records of the selectmen reveal a constant concern with military matters. On 16 March 1702, for instance, the selectmen and justices, including John Clark, Esq., met to agree on places for the “Lodging of Gunpowder.”562

Several matters which are quite significant in the records of the selectmen and the separate records of the town have no analogue in Clark’s book. A frequent topic of concern with the town was the arrival of people likely to need poor relief.563 The names and circumstances of such arrivals were referred by town officials to the general sessions. Except for a few illegitimacy cases which had a flavor of this, Clark had no cases of this kind as a single justice.

Another set of issues frequently discussed by the justices with the selectmen at their joint meetings, but not reflected in Clark’s book, are those involving highways, town property ownership, and boundary matters. Thus the decision made by the justices together with the selectmen on how to compensate people whose homes were blown up to stop an advancing fire on 9 October 1710 had no single-justice aspect.564 Also, the many decisions on road, path, and wharf matters are not reflected in litigation before a single justice.

Clark handled some purely ceremonial municipal matters. He swore in an occasional municipal officer: John Brockus, as military clerk of Colonel Samuel Checkley’s company,565 and Josiah Winchester as Town Clerk of Brooklyn [sic].566

The remaining regulatory matters recorded by Clark constituted violations of numerous petty municipal ordinances. John Prichard was fined twenty shillings for buying a turkey on Boston Neck on 7 January 1714/15.567 Samuel Burrel was fined twenty shillings for having a black servant sweep his chimney “without the approbation of the selectmen of Boston.”568 William Robie paid twenty shillings after being convicted of cutting wood “not measured by a sworn corder nor viewed and found measured by the officers appointed for that end by the selectmen.”569

D. Civil Matters

The civil jurisdiction of a Massachusetts justice of the peace was stable and substantial throughout the period of John Clark’s justiceship. It extended to “all manner of debts, trespasses and other matters not exceeding the value of forty shillings (wherein the title of land is not concerned).”570 Civil cases in the book outnumbered criminal by two to one. The vast majority of the civil cases concerned collection of a debt or contract-type damages. Since a large number of these cases involved claims for thirty-nine or forty shillings,571 it would appear that people sought out justices of the peace in general572 or John Clark in particular.

The first major class of civil matters involved confessions of judgment:

March 24 [1701] John Tuckerman of Boston Cordwainer acknowledged Judgment against his person and estate for the sum of twenty-one shillings due to John Coomer Junior of Boston Pewterer.

April 15th Execution Granted.573

The book contains sixty-three such acknowledgments, nine of which have subsequent executions noted, like Tuckerman’s. Not much can be gleaned from the confessions except that their number suggests that creditors knew enough of the English practice to understand that a confessed judgment provided a quicker and surer remedy than a regular law suit.574

By contrast, civil proceedings for the collection of a debt or contract-type damages reveal a good deal of interesting legal information. In supporting the prosecution of a number of these cases, bills of exchange or notes were introduced as evidence. The existence of a bill or note was usually revealed in cases which threatened to go by default.575 John Clark would not enter judgment in a defaulted debt or contract proceeding without a showing of proof beyond the plaintiff’s bare allegation:

January 2. Christopher Webb of Boston Tailor plaintiff versus John Wakefield of Boston Shipright defendant. Default. The defendant not appearing the plaintiff produced a bill for 40 shillings endorsed accepted by the defendant. Whereupon I give judgment that the defendant pay to the plaintiff the sum of 40 shillings money sued for and cost of suits 6/. Execution issued January 4.576

In one of the defaulted bill of exchange cases, Clark noted that the defendant had been “thrice called.”577 Most entries do not indicate that defendants were called, and there is no explanation why in that particular case and a few others Clark mentioned that the defendant had been summonsed three times. English common law had from the earliest time abhorred and avoided default judgments.578 Thus John Clark’s occasional references to a defendant being called three times are perhaps merely an example of how general notions of fairness derived from the common law may have seeped, without explicit adoption, into the law of Massachusetts. Such a generalization does not explain why some people got the benefit of the three-times rule and others apparently did not. A clue may be found in Chapter 20 of the Province Laws of 1700–1701579, which provided that in a suit in which goods or other property were attached the defendant, if “not an inhabitant or [who was a] soujourner within the province, . . . or [who was to] be absent out of the same at the time of the commencing such suit, and shall not return before the time for trial,” could not be defaulted until he had been summonsed on three separate occasions. In the case mentioned at the beginning of this paragraph, the defendant was a mariner and it may have been that John Clark applied something like the rule in attachment cases.580

In most debt or contract-type matters there was nothing as damning against the defendant as a signed note or bill. If the defendant failed to appear, the plaintiff generally would produce and swear to a “book” or account. An entry for 11 September 1701 is illustrative:

Elijah Doubleday of Boston Butcher petitioner versus John Chadwick of said Boston sailor defendant in a plea of the case for the value of eighteen shillings and six pence due by book for meat sold him and the defendants not appearing at the time and the petitioner making oath to his book Judgment is granted by Default for 18s and 6d and costs of suit.581

In some cases this pattern varied slightly; the wife of the petitioner582 or a servant583 might swear to the book or account. In one entry Clark wrote that the account was annexed to the writ584 commencing the litigation. Finally, one Sarah Horton, not having a book to swear to, made her case in the face of the defendant’s default by the testimony of two witnesses.585

Evidence in Clark’s book suggests that books and accounts formed the evidentiary basis for most contract and debt-type proceedings, not just defaulted cases. Thus, in a contested case586 Thomas Webber’s wife testified that she had kept a running account of John Pitts’ debt on a wall partition but had removed the partition and transcribed the figures into a book, the accuracy of which she then affirmed. Clark entered judgment for Webber in the amount of thirty-eight shillings based on his wife’s testimony and the defendant appealed.

A number of civil matters involved collection of contract damages. Several cases reveal that the petitioners would estimate the liquidated value of performance in a contract case and sue for that amount. Clark, on several occasions, ordered payment of the liquidated sum or, as an alternative, partial or complete performance.587 Samual Parrot, a tailor who apparently failed to do his job, was ordered to pay the petitioner thirty-six shillings or return “so much of the materials as were taken up for the jacket and breeches mentioned in the attachment.”588 Isaac Spencer, a gunsmith, was forced to return the “fusee or musket sued for” or pay thirty shillings and costs.589 Nathan Millet of Gloucester, a boatman, was to “fulfill the bargain and deliver” some lumber at the promised price or pay the petitioner six shillings and costs.590 Finally, the irrepressible Job Bull was to give over a ring sued for—perhaps by a disappointed fiancee—or pay twenty-six shillings money “in lieu thereof.”591

The most enduring debate about colonial legal history has been over the extent of, and methodology by which, English common law was received in Massachusetts. A few tantalizing references in Clark’s civil cases seem to show that Clark and his litigants were familiar with some common law terminology. A number of the contract-type actions were referred to as a “plea of the case.”592 It does not appear that this usage or its absence implied anything particular in a civil action. In some cases it referred to an action to recover on a bargain,593 but in others it was employed in an action to collect a money debt.594 Another common law reference, although an isolated one, occurred when William Jephson brought an action of replevin to obtain two of his cows which were “wrongfully and illegally impound[ed]. . . .”595

Justices of the peace could hear actions in trespass “wherein the title of land [was] not concerned.”596 The Province Laws provided597 that if a litigant demurred to a single justice’s jurisdiction on the basis of a claim of title, then he would have to make a recognizance guaranteeing that he would prosecute his claim of title at the next session of the inferior court of common pleas for the county in which the trespass occurred. Only four actions are identified by Clark as “trespass,” and in all of them the defendants demurred based on a claim of title.598 Case actions are not referred to as trespass actions.

Clark’s book does not give much insight into the dynamics of civil litigation. He seems to have had a liberal attitude to adjournments and continuances. Some may have been involuntary, because of the defendants’ absences, but others seem to have been at the request of the parties, perhaps while they tried to settle.599 One trial device which Clark used in contested contract cases was reference to auditors:

John Pedley of Boston Joiner plaintiff versus Joseph Essex of Boston aforesaid Watchmaker defendant. The defendant pleads that the work is not worth half the money that the plaintiff sues for whereupon by the agreement of both parties Mr. Frogley and Mr. Whittemore are appointed to view and appraise the work and make their report to me.600

Clark’s judgments were usually in a form whereby the defendant was ordered to pay the plaintiff the money sued for. Occasionally the defendant won. No matter what party eventually prevailed, Clark seems to have assessed costs, in an unspecified amount, on the loser. On rare occasions Clark found for the plaintiff but reduced the amount sought.601 This was perhaps a result of his own evaluation of the evidence introduced in cases in which the right sought to be enforced was not a simple money debt.602

Litigants could appeal Clark’s determination of the merits to the inferior court of common pleas.603 Twenty-seven parties sought such appeals by making recognizances to Clark, usually in a fairly modest amount, which secured their promise to appeal. One case involving Job Bull suggests that appeals were discouraged. On 29 June 1713 Bull lost by default an action to collect thirty-three shillings, six pence.604 Clark recorded Bull’s recognizance one day later but subsequently wrote in the margin:

Memorandum. The appeal being granted after the court was risen and the plaintiff was gone the law not allowing such liberty. It considered further and upon the plaintiff[’s] instance issued out an execution July 7th.605

Justices of the peace depended on the effectiveness of writs of execution in view of the large number of defaulted civil actions. Clark’s book reveals that nine cognovits resulted in executions and ninety executions issued on regular judgments. On very few of the execution entries is there a subsequent notation. In one case Clark noted “Returned Satisfied Costs 5s Oct. 1” on a judgment made on 5 May 1712.606 On an execution of 20 July 1714 he wrote, “Not paid the while.”607 No inference as to the efficacy of such executions is possible in view of the incompleteness of the record. One prevailing plaintiff refreshingly relinquished his judgment because he suspected that his writ was “false laid.”608

The geographic and social status of the civil litigants before Clark is a little clearer than that of the criminal litigants. Chart B of the Appendix includes all cases recorded for the year 1 January 1713/14 to 31 December 1714 and shows that the contestants were overwhelmingly from Boston.609 Because debts do not occur on a street corner, unlike assaults, there is less evidence to tie the civil cases to a particular part of Boston, like the north end. Several names, particularly Job Bull’s, recur in civil matters. Chart B also shows that small shopkeepers and manufacturers, cordwainers, victuallers, and innholders, who might be expected to have had numerous modest-sized debts, used Clark’s justice court frequently. They also tended to prevail. By contrast, people of lower status occupations, unknown occupations, mariners, and carpenters tended to be the defendants and tended to lose.

Occasional bits of additional information are of interest. As compared with Clark’s criminal cases, only one civil case involved a black or Indian as plaintiff. Several legal representatives of decedents’ estates610 sued; one trustee sued611 and one gentleman was sued. The entry concerning the gentleman may suggest the power of high social status before a local justice of the peace like Clark.

May 22 [1710] Mary Baker Widow Relict and administratrix of Nathaniel Baker of Boston, Baker deceased. Plaintiff versus John Harris of Ipswich in the County of Essex gentleman Defendant. The plaintiff and defendant both appearing and the plaintiff refusing to enter the action the defendant prayes his costs of suit which is accordingly granted him.612

E. Miscellaneous

Two striking facts about the legal system revealed in Clark’s book merit discussion apart from the relationship to the substantive law—the absence of attorneys and the heavy reliance on recognizances. John Winthrop’s dislike613 for common law lawyers had given way to statutory toleration by the time John Clark started his book. Chapter 7 of Province Laws of 1701–1702614 permitted an attorney to appear “in any suit” if he took the prescribed oath. Legal fees were limited in Superior and Inferior Court actions, but no fee was set for appearing in an action in a court of a justice of the peace. The statute also provided that “none but such as are allowed and sworn attorneys as aforesaid shall have any fee taxed for them in bills of costs,” implying that fee awards were paid by losing litigants.

The word attorney appears in John Clark’s book on merely ten occasions. The only person identified as an “Attorney at Law” was one Ralph Lyndery of Boston,615 who was convicted of stealing some neckcloth and a pair of worsted stockings. Five of the occasions involved the appearance of a near relative, a son or wife, to perform a task in the court for an absent litigant:

[September 10, 1711] Thomas Hitchburn of Boston Joiner, Plaintiff, versus Mary Daftorn of Boston aforesaid Widow defendant in a plea of the case for not paying to the plaintiff the sum of forty shillings due according to attachment. The defendant appeared by her son Isaac Daftorn of Boston Cooper by a power of attorney who pleaded that the defendant owed nothing as set forth in the writ. Whereupon the plaintiff made oath to the account in his book and the evidences in the case being heard I give judgment that the defendant pay the petitioner the sum of forty shillings sued for and costs of suit. From which judgment the defendant hath appealed.616

On two of these occasions the family member confessed a judgment.617

In only four cases does the designation “attorney” appear for a party in which no familial relationship is mentioned. A Mr. Gee appeared to make out a debt on behalf of the petitioner, one Nathaniel Gookin of Sherborn.618 Joseph Billings was “admitted attorney for the defendant” and won a case of undeterminable subject matter.619 An attorney appeared for William Coffin, a mariner, to make out his debt against a non-appearing defendant.620 The conclusion to be drawn from the foregoing is that, while Clark was familiar with the concept of an attorney, no attorneys at law, as such, appeared in his court.

Equally striking to a modern reader is Clark’s almost exclusive reliance on recognizances to guarantee that individuals perform something—prosecute appeals to the Inferior Court of Common Pleas,621 appear as witnesses,622 or leave others alone. The recognizance was in a money amount with a surety for performance. Not a single recognizance given with a surety is executed upon in Clark’s book. In one case,623 William Thomas, a mariner, did not produce a surety so he was “recognized to his majesty King George in the sum of 20 pounds to be levied on his goods and chattels land and tenements [and] in what thereof on his person” if he defaulted. The book noted a later sale of some goods on this pledge. Whether this lone example of an enforcement of a pledge proves that all the others worked is perhaps too speculative a matter, but Clark’s book does give the impression that the recognizance system worked reasonably well.

F. The Significance of the Book of John Clark, Esq.

A single record or book covering the period 1700 to 1726 cannot be safely used to characterize Massachusetts society, its legal culture, major intellectual developments in law, or even the institution of the single justice of the peace. Clark’s book is evidence which must be fitted into a larger picture.

English law provides a perspective by which to assess the significance of Clark’s book. Although there have been few English local histories focused on a single justice and even fewer editions of justice of the peace records,624 the impression that one gets from Clark’s book is of a judicial world not far from that depicted in the 1705 edition of Dalton’s The Countrey Justice or the other contemporaneous English justice of the peace handbooks. Clark’s criminal and regulatory jurisdiction, both as a trial judge and magistrate, are consistent with the broad outlines of Dalton’s. The two worlds diverged in that Clark’s civil jurisdiction was much more robust than that of an average English justice of the peace.

Another perspective on Clark’s book is Massachusetts legal history. In recent years two somewhat polar positions have been staked out on the development of Massachusetts Bay law from 1630 to 1700. David Konig625 has argued that the earlier settlers possessed a communal ideal, which led them to de-emphasize the formal dispute settlement procedures of English law in favor of community accommodation mechanisms. Konig believes that the substance of the law began to change, and these procedures dropped away, when the original ideal ceased to be widely held. The law reflected this change, but also helped to advance it.

Konig’s thesis is based on the belief that a good deal of English law and institutions came along with the communal ideal, and, in particular, that the magistrate central to the Lawes and Libertyes of 1648 was patterned on the English justice of the peace. The popularity of the office of justice of the peace with the Puritans in England and Massachusetts sprang from its local identification and the occasional refusals of English justices to enforce central policy. The justice of the peace was installed in Massachusetts because he was a local figure, but, as Massachusetts moved away from the communal ideal, the institution of the justice was left to increase its power and judicial business.

William E. Nelson’s latest book626 describes a similar pattern of change in Plymouth County from communal dispute resolution to reliance on formal legal structures. Nelson’s book places that change in the century from 1725 to 1825, and, but for this dating, it seems to agree with the Konig model, which may itself have been generated by Nelson’s first book.627 This is not to say that Nelson has necessarily endorsed Konig’s view on the extent of importation of English law into Massachusetts.

At the other pole from Konig are the innovationists: scholars like Barbara Black628 who think that the Konig approach misses the extent of legal innovation in Massachusetts. Professor Black has written that Konig’s thesis on the magistrate’s equivalency with the English justice of the peace ignores the source of the magistrate’s power—and the essence of his office—his position as an assistant.629

The professionalism of the Clark book, and the number and detail of statutes passed regulating justices of the peace after the granting of the second charter in 1691, indicate that the justice of the peace was well established in Massachusetts in 1700. The book also shows that a single justice was in no sense concerned with the whole “community” of Boston. High status people are missing; perhaps they used other justices, but this is doubtful. Thus, while the justice courts may have been small scale, they did not handle randomly matters which concerned the entire community.

These conclusions would seem to support Konig’s view that the office of the justice of the peace was congenial to the Puritans and therefore was quickly and solidly established in the magistrate analogue. They would also seem to raise questions about whether the pattern which William Nelson notes in Plymouth was even close to that in urban Boston. Nelson, of course, had no justice records comparable to Clark’s for Plymouth during the 1725 to 1825 period.630

The evidence of the social status of the litigants in the Clark book should lead the participants in the debate to rethink the meanings of the words “communal” and “community.” If Boston was several economic communities or clusters in 1700, was it really one cohesive group in 1650? Was Plymouth ethically unified in 1725? The justice of the peace in England was more a local figure than a representative of some communal or medieval ideal. The strength of this institution in England, and then in Massachusetts, may have been in the familiarity of its officials and the surroundings of justice, in the scale of its grandeur and the modest size of most issues confronted. The economic divisions of the judicial system, shown in Clark’s book, may indicate that there was never a “communal” ideal, because there was no single community.

A third perspective on Clark’s book is how it fits into theories about the development of the criminal law in eighteenth-century America. The dominant insight, which others have modified or refined but for the most accepted, has been William E. Nelson’s claim that the criminal law evolved from a religiously oriented construct at the beginning of the eighteenth century to a property oriented one at the beginning of the nineteenth. In his first book Nelson placed this change near the end of the eighteenth century.631 In a recent article632 Richard Gaskins has argued that the change occurred earlier in Connecticut. Nelson did not have much data on justice of the peace records; Gaskins relies on them.

The Nelson thesis can be challenged on three grounds. First, the data on eighteenth-century criminal law is so incomplete that major generalizations are not possible. Even if one can discover changes in the numbers or type of prosecutions, it is dangerous to derive grand interpretations from them. John Clark’s book provides at least more data, but a long study of it makes one even less willing to contemplate making grand generalizations based on an aggregate of similar materials. Clark’s book, like all such records, while fascinating, is sui generis. As any criminal sociologist will attest, records, even if excellently kept, are only evidence of convictions which may represent an unreliable indication of the purposes and impact of the criminal law.

A second possible challenge to the Nelson thesis begins with a concession that “religious-type” offenses probably diminished in number and property offenses increased in the eighteenth century. Such a change does not necessarily show an alteration of an ethical consensus about the purposes of the criminal law. It may instead show something quite different. If one accepts that the criminal law is in large part designed to define and control deviance, as Kai Erikson has argued,633 it may be that the substantive content of the rules applied is less significant than Nelson and others have supposed. Why then did Massachusetts judges seem to apply moral law as opposed to property law more frequently at the beginning of the eighteenth century? There are several explanations, none of which is refuted by Nelson’s data. For instance, it may be that property type offenses were rarer in an absolute sense in the early part of the century. With the Revolution and the post-Revolutionary economic problems, property offenses might have become more common and deviance control was being performed adequately by the property offenses.

A third possible challenge has been put forward by Robert Gordon in an excellent review634 of Nelson’s first book. Does the law immediately reflect changes in underlying social values? Do social values change quickly? Law and legal institutions seem resistant to such changes. John Clark’s book reinforces this notion. A comparison of the book with Dalton and other justice of the peace manuals from England shows great similarities. The justice of the peace is a solid, local community figure who administers quick justice to the lower classes of the population. The major modification in Massachusetts is that John Clark is handling a large volume of civil cases in which he is acting as a debt collector for small shopkeepers. This may have been done by others in England, but it seems to fit in with his position in Massachusetts.

In sum, John Clark’s book does not support or refute any of the great claims made in the latest scholarship on eighteenth-century legal history. A generation ago, John Dawson noted that a major divergence between English and French law was English tenacity or luck in holding onto local institutions charged with enforcing the law. Whether he was correct that these institutions and their longevity were an important part of the creed of “constitutionalism” is beyond the scope of this paper. Nonetheless, Professor Dawson was surely right when he observed that as these local institutions “evolved they left larger room than was provided elsewhere in Europe for wide participation by untrained people—not only in the process of judging disputes but in all the processes of government that clustered around that vital center. There was wisdom, no doubt, in retaining them and in letting their meanings unfold.”635

CHART A—CUMULATIVE

CHART B

Entries in John Clark, Esq.’s Book from 1 January 1713/14 to 31 December 1714

| A. Matters 87 (Civil & Criminal) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. Civil Actions | ||||

| 1. Residence | ||||

|

Plaintiff residence |

||||

|

Salem |

5 |

Unknown |

4 |

|

|

Boston |

60 |

|||

|

Defendant residence |

||||

|

Boston |

57 |

Dorchester |

3 |

|

|

Salem |

2 |

Unknown |

5 |

|

| 2. Disposition | ||||

|

Heard the case |

18 |

|||

|

Cognovit |

2 |

|||

|

Continuance |

7 |

|||

|

Appealed |

6 |

|||

|

Defaults |

45 |

|||

|

1 |

||||

|

Disposition not revealed |

9 |

|||

|

No won/lost disposition |

1 |

|||

|

Recognizance |

9 |

|||

|

Auditors empaneled |

2 |

|||

|

[Executed later per entry] |

2 |

|||

|

[Later judgment per entry] |

2 |

|||

|

Execution ordered or noted |

6 |

|||

| 3. Prevailer | ||||

| a. Residence | ||||

|

Salem |

2 |

Unknown |

4 |

|

|

Boston |

Charlestown |

1 |

||

| b. Plaintiff or Defendant | ||||

|

Plaintiff |

57 |

Defendant |

1 |

|

| c. Occupation | ||||

|

Innholder |

6 |

Haywright |

1 |

|

|

Sailmaker |

1 |

Blacksmith |

1 |

|

|

Shipwright |

4 |

Joiner |

1 |

|

|

Cordwainer |

9 |

Fence Viewer |

1 |

|

|

Wharfinger |

3 |

Housewright |

3 |

|

|

Mariner |

2 |

Clothier |

1 |

|

|

Unknown |

4 |

Merchant |

1 |

|

|

Widow |

5 |

Glover |

1 |

|

|

Victualler |

8 |

Tailor |

1 |

|

|

Barber |

1 |

Pewterer |

1 |

|

|

Retailer |

3 |

Shipkeeper |

1 |

|

| 4. Civil Loser | ||||

| a. Residence | ||||

|

Boston |

49 |

Dorchester |

3 |

|

|

Salem |

1 |

Roxbury |

1 |

|

|

Unknown |

5 |

|||

| b. Plaintiff or Defendant | ||||

|

Defendant |

58 |

Plaintiff |

1 |

|

| c. Occupation | ||||

|

Wigmaker |

1 |

Mariner |

5 |

|

|

Bricklayer |

4 |

Cordwainer |

1 |

|

|

Innholder |

3 |

Sadler |

2 |

|

|

Joiner |

5 |

Ship carpenter |

1 |

|

|

Cooper |

2 |

Carter |

2 |

|

|

2 |

Sailmaker |

4 |

||

|

Unknown |

7 |

Widow |

2 |

|

|

Shipwright |

5 |

House wright |

2 |

|

|

Laborer |

3 |

Varnisher |

1 |

|

|

Tailor |

4 |

Fisherman |

1 |

|

|

Husbandman |

1 |

Blacks (occupation not given) |

2 |

|

|

Mason |

1 |

|||

| C. Criminal | ||||

| 1. Victim Residence | 2. Offense | |||

|

Noodle Island |

1 |

Profane cursing |

1 |

|

|

Boston |

4 |

Profane swearing |

1 |

|

|

No victim |

6 |

Breach of peace |

5 |

|

|

Unknown |

4 |

Theft |

1 |

|

|

False report |

1 |

|||

| 3. Victim Occupation | ||||

|

Servant |

1 |

Wife of a mariner |

1 |

|

|

Tailor |

1 |

Mariner (by his Captain) |

1 |

|

|

Unspecified |

4 |

Joiner |

1 |

|

|

Merchant |

1 |

|||

| 4. Defendant Residence | ||||

|

Boston |

7 |

Unknown |

7 |

|

| 5. Defendant Occupation | ||||

|

Butcher |

1 |

Merchant |

2 |

|

|

Singleman |

1 |

Captain |

1 |

|

|

Surgeon |

1 |

Joiner |

1 |

|

|

Unknown |

5 |

Sailor |

1 |

|

| 6. Conviction Appealed by a Recognizance |

2 |

|||

| 7. Committed to Perform |

1 |

|||