APRIL MEETING, 1905.

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held at No. 25 Beacon Street, Boston, on Thursday, 27 April, 1905, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the President, George Lyman Kittredge, LL.D., in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

The President appointed the following Committees in anticipation of the Annual Meeting:

To nominate candidates for the several offices, — Mr. S. Lothrop Thorndike, Dr. Charles M. Green and Mr. William C. Wait.

To examine the Treasurer’s accounts, — Messrs. Thomas Minns and Augustus P. Loring.

The Corresponding Secretary reported that a letter had been received from Mr. Ellas Harlow Russell of Worcester accepting Resident Membership.

The Council reported that the consideration of the subject of permanent quarters, referred to it by the Society at its last Stated Meeting, had been committed to the Finance Committee with instructions to report at a future meeting of the Council.

Mr. George F. Tucker read a paper on the name of the Town of Barnstable, which was discussed by President Kittredge and Mr. Henry E. Woods.

Mr. Francis H. Lincoln communicated the Report of a Committee of the Town of Hingham, in 1779, on the Resolves of the Concord Convention of the seventeenth of July of that year fixing the prices of commodities, and extracts from the Town Records of Hingham relating thereto. These follow.

I

REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF THE TOWN OF HINGHAM, 1779.

The Committee appointed to take into Consideration the Resolves of the Convention at Concord of the 17th of July & Apportion the different Articles of Traffick Labour Manufacture &c: have Carefully Attended that duty, & find that an Average porportion of the Country produce there mentioned is a mean of Twenty for one or Twenty times as much as said Articles were formerly sold for, and knowing no Reasons why Labour & other Articles should Be Restraind to a less proportion have made that our Chief guide, Expecting the Vertue of a people duly sensible of the Importance of putting a Stop to a further depreciation of our Currency will be sufficient for all our defects herein, We therefore submit the following Resolves to your Candid Judgment —

1tḥ̣ Resolved that from & after the Tenth day of August Instant the following articles of poduce Manufactures Labour &c: be not sold at higher price than is hereafter affixed to them Viz W: India Rum £6 — 6ṣ pṛ Gallion N: England Dọ̣ £4 —16 Molosses £4 — 7 Coffee 18s/ pṛ ℔ Brown sugar from 11s/ to 14s/ pṛ̣ ℔ Chocolate 24s/ pṛ̣ ℔ Bohea Tea £5. 16 pṛ ℔ Cotton 36s/ pṛ ℔ German Steel 36s/ pṛ ℔ Salt of the best Quality £9. pr Bshel

|

Indian Corn |

£4—10 |

|

pṛ̣ Bushel |

|

Fresh Beaf |

|

£0—5—9 |

|

Rie |

6—0 |

till Sepṛ̣ then |

0—4—9 |

||||

|

Wheat |

9—0 |

Mutton |

4—0 |

||||

|

Barley |

2—16 |

Veal |

4—0 |

||||

|

Oats |

1—16 |

Lamb |

4—0 |

||||

|

Beans |

9— 0 |

Butter |

12—0 |

||||

|

Potatoes |

1—10 |

Cheas |

6—0 |

||||

|

Turnips |

1— 0 |

Candles |

15—0 |

||||

|

Rawhides |

4—6 |

||||||

|

hogs fat |

9—0 |

Wool of the best Quality by the fleas 26/8 pṛ̣ ℔ other Wool in proportion Yarn stockings of the Best Quality 50s/ pṛ̣ pair other Stockings in proportion Plain Cloth of the best Quality 3/4 wide of Common Mill Colour £6-pṛ̣ yard Other Woolen Cloth in proportion Flax 13/4 pṛ̣ ℔ Good Linning & Tow Cloth shirting 7/8 wide 32s/ pṛ̣ yḍ̣ all other Linning in proportion Soal Leather 22s/8d pṛ̣ ℔ Currying Leather 45s/ pṛ̣ Side Dọ̣ Calves Skins 22s/6d Good Neat leather Mens Shoes £6–6 pr pair Womans Dọ̣ £5–5 Other Shoes in proportion Oak bark £20— pṛ̣ Cord Hemlock Do: £13—6–8 pṛ Cord Good oak Wood £12 pṛ̣ Cord Other Wood in proportion, White Oak plank £120 pṛ̣ Thousand other plank in proportion pine boards Merchantable £40 pṛ̣ Thousand Cedar Timber For Coopers £48 pṛ̣ Load, pails from £5 to 9 pṛ̣ doz: Other Ware in proportion, Good Cedar Rails £18 pṛ̣ Hundred, Good White Oak Barrel Staves £60 pṛ̣ Thousand Red oak Do: £40 pṛ Thousand — Good white oak Cyder Barrels £4 Fish Barrels £2–13–4 and all Other timber not here Specified 20 times as much as formerly, English hay £35 pṛ̣ Ton, Other hay in proportion Milk 2/3 pṛ̣ Quart Bloomery Iron 30£ pṛ̣ Hundred, Shoeing Horses £4–16–8 Other Country Woork in proportion Axes £6–15–Ship Carpenters Labour £4 pr Day Spinning Linning 26/8 pṛ̣blue, Other Spinning in proportion Freighting Wood to Boston on[e] fifth part of the price of the Wood at the Landing in Hingham Other freighting Twenty times as much as formerly, Teaming Woork and all other Labour both of mens & Womans and all Articles of produce not here Specified Twenty times as much as formerly, — And a Right Understanding among the people of the manner that the Resolves of the Conventions are to be Conceived of is highly Necessary for a fair & Just method of Carrying them into Execution, and on Viewing letter & Spirit of Said Resolves are of Opinion that in Order to Appreciate the Currency one essential point therefore is to Impress the minds of the possessors with such a faith in it as shall Naturally Induce him to get and keep it; and in Order to Effect said purpose, it is

2ḍḷy Resolved that the Exchanging one Commodity for another or Silver & gold be practised only under the Restrictions of A Committe Chosen for that purpose of dispationate Judicious Men as it must in its Tendencies Otherwise have pernitious and fatal Consequencies to a paper medium, it Would give an Opening for bad & Designing men to With:hold their Commodities for an Oppertunity of Exchange which Ought not to be, but that every person haveing a Surplus of Articles produce &c: more then for his own Family Consumption Shall be Obliged to part with a Reasonable Quantity for his Neighbours precent use & to Receive the Currency therefor —

3dly Resolved that their be A Committee to Serve as Watchmen among us and hear all Complaints and act thereon or lay the Same before the Town, and that these Resolves be Offer:d to every Male Inhabitant in the Town for their acceptance or Non Acceptance there’of pṛ̣ Order of the Committee,

Charles Cushing Chairman

Hingham Augṭ̣ 2ḍ̣ 1779

A Copp

[Filed]

Report of A

Committee in 1779 on

Prices of Articles

Charles Cushing, Chairman

Copy.

II

EXTRACTS FROM THE TOWN RECORDS OF HINGHAM, 1779.

Town Meeting, July 5, 1779.

At said Meeting the Town resolved to send a Committee to meet with the several Committees in this State at Concord174 to affix prices to the articles of Labor, produce &c. and made Choice of Doctr Thos Thaxter & Capṭ Charles Cushing for a Committee.

Adjournment of above meeting, July 26, 1779.

Resolved to act on the third Article in the warrant which was to take into Consideration the resolves of the late Convention at Concord. At the same Meeting of the town resolved to accept of the prices affixed to the several Articles mentioned in the first resolve and resolved to Choose a Committee to Consist of 15 to affix prices to Manufacture, Labor, Produce &c: and Chose Capṭ Charles Cushing [and fourteen others].

Voted that the aforsḍ Committee take up the resolves of the Committee of Concord at Large and Come into Measures of Apportioning on the different articles of Traffick Labor &c between the inhabitants of said Town, and be laid before them at the Adjournment of this Meeting. . . .

Adjourned the meeting to Tuesday the third day of August next at four OClock in the afternoon.

Met on the adjournment and Voted to Accept the report of the Committee chosen to affix prices to Traffick Labor &c in this town.

Mr. Andrew McFarland Davis read the following paper on —

THE LIMITATION OF PRICES IN MASSACHUSETTS, 1776–1779.

The paper submitted by Mr. Lincoln is of great interest, and is worthy of our study, not because the character of the document is unique or the action taken by the town individual, but because the opinions expressed represent the feelings of the average New England town at that time. Such was the typical outcome of the struggle against the rise in prices for which at the outset the war was mainly responsible, a responsibility, however, which at a later date was subordinated to the influence of the inflated currency. The expressions of opinion and the recommendations for action in this document also command our attention because they represent a stage of economic thought. Against the evil for which the townsmen of Hingham sought a remedy, Committees of investigation had been appointed in the Assembly, Committees of Conference from different States had sat in Conventions; Acts limiting prices and prohibiting transportation had been passed; embargoes had been declared; and legislation bearing upon the subject, in the form of Laws or Resolves, as the case might be, had followed so thick and fast that it was difficult from day to day to tell what one could do in the way of trade or what one might be permitted to own in the way of provisions.

Even before the premium upon silver and gold had become so pronounced as to be much of a factor, the disturbance to commerce and to local industry produced by the war, had caused a rise in bread-stuffs and other necessaries of life of sufficient importance to stir up the community. In the scale of depreciation adopted in 1780, by means of which debts were to be adjusted, the first date at which the depreciation was considered of enough importance for recognition is January, 1777, when the premium on coin was fixed at five per cent. Yet as early as February, 1776,175 a committee of Representatives was appointed to take into consideration the high price of goods and recommend what action ought to be taken in consequence thereof. For some months thereafter, petitions poured in to the Assembly representing that merchants and farmers were charging exorbitant prices for their goods, and praying for legislative relief.

June nineteenth, 1776,176 the Assembly by Resolve temporarily prohibited the transportation of provisions out of the State. September fourth, 1776,177 another temporary Act was directed against the exportation of lumber.

The concurrence of sentiment in the different States that some joint action of a remedial character ought to be taken, led to the appointment by the Assembly on the sixteenth of November, 1776,178 of a committee of conference to meet similar committees from the other New England States on the tenth of December at Providence, Rhode Island. Under the instructions given the Massachusetts delegates they were to prepare propositions for the regulation of the currencies of the States to be submitted to the Continental Congress. Before the delegates left for Providence their powers were enlarged to comprehend also the following subjects: The prevention of monopolies; the limitation of prices; the regulation of vendues; the placing of embargoes on shipping; and such other matters as were of general concern and not repugnant to the powers of the Continental Congress.

The Resolve prohibiting the transportation of provisions out of the State during the summer of 1776, had in the interim expired, but that the condition of affairs which prompted this Resolve still continued is shown by the fact that on December second, 1776,179 power was conferred upon the Board of War to impress goods for the use of the army and that on the seventh of December180 an embargo was laid on all vessels. This was followed by the passage of a Resolve on the seventh of February, 1777, which was amended April twenty-third, prohibiting the transportation into other States of rum, molasses, and numerous other articles. These Resolves were known as the Land Embargo and were repealed September fifteenth, 1777.

December tenth,181 about two weeks before the Providence Convention actually met, a committee of the Assembly was appointed whose function it was to propose a conference of committees from the New England States to meet in Connecticut for the purpose of discussing the exact questions included in the additional powers given the delegates to Providence. The amended instructions to these delegates probably represent the result of this appointment.182

The Convention of Committees from New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut met at Providence on the twenty-fifth of December and on the thirty-first reported a scale of prices which they recommended for establishment in the several New England States. This scale of prices included pretty much everything, except real estate, for which money could be expended in New England. The report was a voluminous document and represented a prodigious amount of labor. On the twenty-fifth of January, 1777,183 the recommendations of the Convention in regard to prices were accepted in Massachusetts and bodily incorporated in the Statute entitled An Act to prevent Monopoly and Oppression. This Act as originally passed had no time limit. In May it was amended and a time limit of three years was set.184

If we turn to the Boston Records we can see how this legislation was brought about and trace its effects during the brief period of its existence. In November, 1776,185 a committee appointed in that town to consider the grievances arising from forestalling wood, provisions, and other necessaries of fife, contented themselves with the minatory statement that for the present they forbore to mention the names of those who by engrossing and forestalling were greatly injuring the town. The engrosser of that day sought to control the market by purchasing all that there was; the fore-staller sought to get possession of the goods before they reached the market. Both operated for a rise, hence both were unpopular.

February sixth, 1777,186 a committee of thirty-six persons, not in trade, was chosen to aid the Selectmen and Committees of Correspondence, Inspection and Safety, in the enforcement of the Monopoly Act. This committee displayed some activity but evidently could not cope with the situation.

In October, 1777,187 the Act to prevent Monopoly and Oppression was repealed. This action was probably brought about through a second conference of Committees of States. The first, it will be remembered, was confined to the New England States. Legislation of this sort to be effective in any State required that similar legislation should comprehend within its scope all the other States with which active intercourse was possible. At this stage of the war this meant that if New York were to co-operate with New England, the conditions would be as favorable as possible under the then existing circumstances, for the enforcement of the restrictions in Massachusetts. The British forces held New York City; their vessels had free access to the Hudson River, and it was still possible that an invading army from Canada might separate the New England States from those farther South. There was a portion of the State of New York, however, with which cooperation was possible, and to secure that co-operation seemed important. June twenty-seventh, 1777,188 a new Committee of Conference was therefore appointed, to meet committees from the other New England States and from New York at Springfield on the thirtieth day of July next ensuing.189 The delegates were to consider the expediency of calling in the paper currency of the States and also what was best to do with reference to the Act to prevent Monopoly and Oppression. In addition, they were to confer relative to the legislation which had been passed to prevent the transportation of certain articles from one State to another.

So far as the currency was concerned, it will be remembered that it was one of the subjects which the Providence Convention had under consideration.190 The recommendations of this body had been conservative. They said that there was too great an amount in circulation and they recommended the several States not only not to make further emissions, but to ‘retire the outstanding bills as they became due, and in future to supply the Treasury by borrowing on interest bearing notes of short terms.

The Springfield Convention met at the appointed time and in the report which, after due conference, they adopted they recommended the calling in of all non-interest bearing notes of greater denominational value than one dollar which had been emitted by the States, thus leaving the field for non-interest bearing notes practically open for Continental bills. The passage, on the thirteenth of October,191 of an Act to accomplish the above suggestions was the response made in Massachusetts.

This Convention also recommended the repeal of so much of the Monopoly Act as attempted to regulate prices. The special evil against which provision was attempted to be made in the Monopoly Act was the rise in prices of provisions and goods in general and it was asserted in the preamble to the Act that this was due to the avaricious conduct of many persons who not only added to the exorbitant prices which were demanded for every necessary and convenient article of life but by this avaricious conduct increased the price of labor. Among the prices which the Assembly undertook to regulate in this Act was that of labor. It was also provided that auctioneers were not to be permitted to receive bids for goods higher than the prices stated in the Act. Individuals were prohibited from “engrossing” or having in possession more of any of the articles enumerated in the Act than was necessary for consumption in ordinary family life.

The recommendation of the Springfield Convention was that all legislation through which the regulation of prices was undertaken should be repealed. The Convention, however, went on to state that they regarded engrossing and withholding from sale the conveniences and necessaries of life and the accumulating of profits on the same by repeated sales as having a fatal and dangerous tendency and they recommended the prohibition of such proceedings.

It will be seen that a part of the Act to prevent Monopoly and Oppression was approved and a part was condemned in this report. The Massachusetts Assembly paid no attention to the suggestion of the Convention that it was only the “regulation of prices” that they wished to have abolished,192 but in its energetic expression of disgust at the failure of this attempt to hold prices down, declared that the Act was very far from accomplishing the salutary measures for which it was intended and that each and every paragraph was repealed. This repeal carried with it the clause directed against engrossers and the sections regulating public auctions. So far as the latter were concerned, specific legislation was from time to time directed against the sale of goods at public auction and this legislation, which by repeated extensions was kept in force for several years, was evidently regarded as having a beneficial effect.193

In September, 1777,194 it was asserted that it was of great importance that cider as well as all kinds of grain, whether imported or produced in the State, should be preserved for the use of the army and the people of the State, and for this reason the distillation of spirits either from cider or from any grain was prohibited.

In November, 1777,195 the Continental Congress divided the States into three groups and recommended them to hold Conventions for the purpose amongst other things of regulating the price of labor, the charges of inn-holders, the prices of commodities, and for the provision of some power for the seizure of goods in the hands of engrossers and forestallers. New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware were requested to appoint representatives who should meet in conference at New Haven, January fifteenth, 1778. Two days before the Convention was to meet, delegates were appointed by Massachusetts and they were instructed that “all Monopolizers, Oppressors, Sharpers, Forestallers and Extortioners” were to be “discountenanced and suppressed.” The New Haven Convention was attended by persons authorized to represent the several States mentioned with the exception of Delaware, and on the thirtieth, after due deliberation, reported a scale of prices. This scale was adopted by several States, but not by all those represented at the Conference. Among the States which did not adopt it was Massachusetts.

Notification of the final decision of the Assembly upon this point was conveyed to Congress in a letter which was dated April twenty-seventh, 1778.196 Pressure was brought to bear to secure a change of attitude in the Assembly on this subject, but this was finally put to rest by the passage in the Continental Congress, June fourth, 1778.197 of a Resolve recommending those States which had passed laws regulating prices to repeal them.

In March of that year, the citizens of Boston having under consideration “the present extraordinary high Price of Provisions” concluded that “One Great Reason of the present Excessive Price of Provisions in this Town arises from the Avarice, Injustice & Inhumanity of certain Persons within Twenty Miles of it, who purchase great Part of the same of Farmers living at a greater Distance & put an exorbitant Advance upon it.”198 They recommended the passage of a law against “the inhuman & unrighteous Practice of monopolizing the Necessaries of Life, & forestalling this Market,” and they suggested that the more opulent citizens should not only subscribe for the relief of their poorer neighbors, but should also agree among themselves “on no Occasion whatever [to] have more than Two Dishes of Meat on the same Day on their Table,” and also to “avoid the Use of Poultry & every other Superfluity as much as possible.” The inhabitants of the town were recommended “to make two dinners per week on fish, if to be had.” A few days after this the town petitioned the Assembly for relief from forestallers of the market and alleged that “their uncommon Sufferings are greatly encreased by the more than Brutish Conduct of these Wretches within a few Miles of this Capital known in the odious Character of Forestallers.”199 They prayed that an “effectual Law” might “be enacted against this Species of Wretches.”200

Meantime, on the eighth of June, 1778, Congress laid a temporary embargo on provisions which was by subsequent Resolve continued in force until January first, 1779, or until sufficient supplies should have been obtained for the Army and the French fleet. The several States were recommended to pass laws for the seizure and forfeiture of grain and flour in the hands of engrossers.

The Act against Monopoly and Forestalling, passed February eighth, 1779, was the response to this appeal. It provided that no person other than bakers could purchase grain or flour, more than would be sufficient to provide for his family, until the next harvest. Bakers could carry a three months’ supply. One year’s supply of meat was permitted.201

While this Act was pending in the Assembly the various town committees of Boston were at work; some collecting money for the aid of the suffering poor, others running down forestallers. February second, one of the Committees having the latter subject in charge, reported numerous instances of forestalling, and Stated that they were seeking proof in sundry cases. The evidence against some of the offenders is given in full in the record, and it was agreed that “the names of all who are found guilty of monopolizing the necessaries of life should be held up to public view.”202 It is presumable that similar activity prevailed elsewhere, but there is testimony, nevertheless, to the effect that the Act was not uniformly enforced. Indeed, this may be inferred from the passage of an Act on the twenty-fourth of June, 1779, in the preamble to which the Assembly alleged that “many people within this State are so lost to a sense of public virtue as to withhold the necessaries of life, and to refuse the public bills of credit of this State and the United States of America for any articles they may have to sell.”203 To remedy this lapse from virtue, it was enacted that no family could have on hand more provisions than were necessary for the support of such family for one year. Provision was made for forcing the sale of any surplus and for compelling the owner to receive bills of credit in payment therefor.

In the spring of 1779, the upward flight of the precious metals when measured in Continental bills was so pronounced that the whole country was aghast at the situation. According to the scale of depreciation twelve hundred and fifteen dollars in these bills were required in May to purchase one hundred dollars in coin, and the depreciation was sensibly progressing from day to day. On the twenty-sixth of May Congress promulgated an address to the inhabitants of America, calling “their serious attention to the great and increasing depreciation of the currency” which they said “required the immediate, strenuous, and united efforts of all true friends of their country for preventing an excursion of the mischiefs that have already flowed from that source.” On the same day a committee of citizens in Philadelphia reported and published a list of prices at which sundry articles stood on the first of May. On the twenty-seventh a general meeting of the citizens of Philadelphia was held in the State House yard at which this scale of prices was reported. Action was taken tending towards maintaining prices at this standard, resolutions were passed against monopolizers, and provision was made for “proceeding in this business and carrying it out throughout the United States.”

The subject was taken up in Boston June sixteenth, when a number of merchants, sitting at the Court House, agreed on resolutions containing a scale of prices to be in force between themselves and further agreeing to limit prices after July first next ensuing to those which prevailed May first, provided the other towns in the State would co-operate. They expressed their approval of the Act against Monopoly and Forestalling and they agreed not to buy silver or gold and not to buy merchandise with hard money.

These resolves were reported to a meeting of the inhabitants of Boston, held at Faneuil Hall, June seventeenth. The committee appointed at that meeting expressed the feelings of those who attended it in a series of resolutions in which they attributed the depreciation of the currency “to Hawkers and Monopolizers who have crept from every hole of obscurity and daring to assume the character of merchants are adding to the miseries of this distressed town.” They approved the resolutions of the merchants and appointed a committee to correspond with Philadelphia. They denounced those who should refuse Continental currency and asserted that such persons ought to be “transported to our enemy.” Further, all those who did anything to counteract the designs of the merchants or who endeavored to evade the salutary measures proposed were “not to be suffered to remain amongst us.” They directed the Committee of Correspondence of Boston to send a circular letter to the other committees of this character in the State seeking for advice as to the measures that could be adopted in the emergency. In pursuance of these instructions the Boston Committee, on the twenty-first of June, called a Convention to be held at Concord on the fourteenth of July, 1779, to take into consideration the measures recommended by Congress.

On the same day that this call was issued the Assembly,204 by Resolve, laid an embargo on the exportation of provisions to continue in force until November fifteenth, and by sundry Resolves of temporary force they prohibited the sailing of all outward bound vessels for several weeks. The embargo on provisions was by Act dated September twenty-third, 1779,205 continued in force until June fifteenth, 1780. The quotations already given from the Resolves of Committees and from the preambles of Acts sufficiently illustrate the bitterness of feeling which was entertained towards those who dealt in provisions. With a currency declining so rapidly that the variations in value from day to day were of importance even in small transactions, the efforts of the seller to protect himself were regarded with jealousy and suspicion. These feelings included not only men but communities. Boston was regarded by its neighbors as being on the lookout for its own interests, while the outlying towns were criticized and abused by the unreasonable fanatics who shut their eyes to the true cause of the situation.

The town of Roxbury had been subjected to abuse for its supposed selfish disregard of the suffering community in Boston. When the citizens of that town voted to co-operate in the Concord Convention, the Continental Journal and Weekly Advertiser, in publishing the resolves passed at the town meeting, stated that “they sufficiently contradict the report of late circulated” that that town “had resolved to sell as dear and purchase as cheap as they could and sufficiently stamp the character of the authors of so gross a falsehood.”206

Another Boston paper, the Evening-Post and the General Advertiser, July seventeenth, 1779, gives the proceedings of a meeting in Boston where it was resolved, “That if any person or persons shall hereafter dare to go over the Neck or Charlestown Ferry to purchase butter or other articles or shall offer more for the same than what is asked they may depend on meeting with the severest resentment of this body without favor or affection.”

The Concord Convention was a complete success so far as numbers were concerned and as there was great unanimity of sentiment they soon agreed upon a scale of prices, which they could and did adopt, but which they had no actual power to enforce. West India rum was the first article, New England rum the second on the list, but there were many solids as well. The Convention resolved that any person who should receive more than the schedule price for any article was an enemy and ought to be treated as such.207 The prices of European manufactures were left to be fixed in the trading towns. Monopolizers and forestallers and dealers in gold and silver were denounced and the towns were called upon to stop such practices. The Convention finally adjourned to meet a second time in October. Azor Orne, the President of the Convention, issued an address in which he said: “The comparative value of silver and gold can be no rule for the price of anything else; as silver or gold might be much more or less wanted than other articles and of course so much dearer or cheaper.” In August, the Boston delegates issued an address to the country towns in which they referred to the good effects of the Convention in allaying the “unnatural jealousy which had for some time before subsisted between the inland and the maritime towns.” The several towns represented at the Convention then separately took action upon the report of doings submitted to them. We have seen to-day what was done in Hingham. The Boston delegates submitted their report on the twenty-eighth of July and voted to take effectual measures to carry the resolutions into execution. The fixing of some of the prices which were left to towns required consideration and occupied some time, but on the sixteenth of August a scale was reported and adopted, and it was voted that any person who should violate the resolutions through which this was effected, should “have his or her name published by the committee hereafter appointed in the Newspapers in this town that the public knowing may abstain from all trade and conversation with them and the people at large inflict upon them that punishment which such wretches deserve to trade or hold any intercourse or conversation with such persons.” It was also voted “that it is the duty of every citizen to keep a vigilant eye upon his neighbor” lest he should infringe upon the resolutions, and if infringements were seen they were to be reported. The sending of servants to the market ferries, to the Neck and to the neighboring towns to make purchases was declared to be opposed to the spirit of the resolution and persons who should do this would incur the resentment of the people. The report was unanimously adopted, and then the trouble arising from the vigilance with which every citizen kept his eye on his neighbor began. Committees were appointed “to be stationed at the fortification and Charlestown Ferry in rotation to prevent persons going out of Boston to purchase provisions.” For some weeks after this, the records show that the attention of the citizens assembled from time to time in Town meeting was devoted to hearing reports concerning the merchants who would and the dealers who would not “adhere to the regulating Act.” It matters but little to us that William Mollineux “treated” the Committee “with indelicate language the effect of high passion,” nor is the indecision of Mrs. Molly Williams who could not determine “whether she would conform as the merchants had raised their goods,” of much importance, yet these facts taken from the records represent the microscopic character of the scrutiny carried on from day to day, and form characteristic samples of the reports submitted to the consideration of the towns-people assembled in public meeting. That Boston must have been in a state of turmoil while such an inquisition as this was going on is evident.208 When Congress passed the resolutions to carry out which the Concord Convention was called, the depreciation was twelve hundred and fifteen in Continental bills for one hundred in coin. The meetings which we are now considering took place in September. The ratio of depreciation at that date was eighteen hundred. In October it was two thousand and thirty. Surely the merchants who sold Molly Williams her goods must from day to day have marked up their stock and one can pardon her for her hesitancy to agree to adhere to any fixed scale of prices, nor should we feel disposed to criticize Jonathan Amory when he told the Committee that “as to rendering an account of goods by wholesale he must think of it.”

This inquisition was too violent to last long. The Concord Convention had voted to hold a second session on the sixth of October, and on the fourteenth of September Boston elected seven delegates. On the nineteenth of October the town received and adopted the resolutions and proceedings of the second Concord Convention and voted as far as possible to carry them into execution. The scale of prices then adopted was headed with articles which were presumably in more general use than rum, whether imported or of domestic manufacture. Indian corn headed the list, followed by rye and rye meal as a close second.

The steady rise in the premium on gold and silver during the interim between the two sessions of the Concord Convention has been noted, yet Walter Spooner, the President of the second Convention, in an address dated October twelfth, says: “The late arrangements had the immediate effect to restore that confidence in the currency which seemed to be failing for want of knowing the true state of our finances.” Whether the attempt to fix prices was actually effectual in this direction may be doubted, but the influence of the Convention was strongly exerted in behalf of loans to the government and was in this respect doubtless effective.

In Concord itself, the home of the Convention, a Committee chosen to fix prices on the articles not enumerated in the Schedule of the second Convention, on the first of November reported “that as the regulations agreed upon by the late Convention had been broken over by the inhabitants of Boston and many other places they thought it not proper to proceed with the business assigned to them but to postpone the matter.”209

If we refer to the Boston Records for evidence of the basis for this statement, we find, as has been already stated, that on the nineteenth of October210 the town voted to carry into execution so far as they could the recommendations of the Convention, and it is also recorded that they then and there appointed a Committee of merchants to “affix the prices of European Goods, Wine &c. Agreeable to the resolves of the Convention.” This Committee reported verbally on the ninth of November211 that they found it impracticable to perform the duty assigned to them. Whereupon a vote was passed calling Thomas Cushing and James Gorham delegates to a Convention lately held at Hartford before the meeting, to report upon the proceedings of the Hartford Convention. What they reported does not appear, but apparently the matter was dropped at this point.

The Hartford Convention above referred to was instigated by the Massachusetts Assembly. In a letter dated September twenty-eighth, 1779, addressed to the other States concerned, the Assembly called attention to the fact that an attempt had been made at Concord to fix a scale of prices, which had practically resulted in an unusual transportation of provisions over the borders of the State, to prevent which, remedial legislation prohibiting such transportation had become necessary.212 The Act of September twenty-third, already alluded to, is the legislation referred to. The Assembly deplored this condition of things and sought for co-operation on the part of the States of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York, to procure which they proposed a Convention to meet at Hartford, October twentieth, 1779. Cushing and Gorham were appointed to represent Massachusetts.213 They were instructed to explain to the other delegates the motives which led to the passage of the embargo kw to concert measures to appreciate the currency and to open a free and general intercourse of trade.

The Convention met at Hartford and on the twenty-eighth of October adopted a series of resolutions. They attributed the various failures of previous attempts to remedy the situation to the multiplied emissions of continental bills. Congress having set a limit for these at $200,000,000, they thought the natural depreciation of the bills in circulation could be determined and a basis ascertained on which reasonable prices for articles of commerce and produce could be fixed. They declared that a limitation of prices would have a tendency to prevent the further rise of provisions, but thought it desirable that all the States as far west as Virginia should accede to it. They, therefore, proposed that a Convention of the New England States, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia should be held at Philadelphia on the first Wednesday of January, 1780. Other resolutions, urging uniformity in legislation on these topics and recommending special steps to be taken by New York to permit the Eastern States to secure flour, were also passed.

The special provision for the transportation of flour from the State of New York to the Eastern States brings before us some of the difficulties connected with the system of interstate embargoes which was then in operation. Wherever the armies had been encamped for any length of time the country was stripped of supplies. The siege of Boston for a time exhausted eastern Massachusetts. The various military activities at Newport paralyzed Rhode Island and brought to the verge of famine some of the small towns in south-eastern Massachusetts. The French fleet and the French soldiers, when at Newport, had but one place to turn for fresh provisions. Connecticut, in touch with military affairs only so far as raids along her western border and one or two raids on the seaport towns of the Sound could affect her, was as a whole well supplied with food. These supplies neither the French allies nor the famishing towns of Massachusetts could procure except by special permits from the Governor designating the amounts to be transported and specifying in detail the purpose of the export.

The report of the Massachusetts delegates to the Hartford Convention was submitted to the Council November eleventh,214 and was under discussion at various dates. Meantime Congress on the nineteenth of November recommended the States to enact laws for establishing a general limitation of prices, to commence their operations February first. It was, however, deemed inexpedient in Massachusetts to take any such action until the report of the Philadelphia Convention should be received. Elbridge Gerry and Samuel Osgood were appointed to represent this State in that Convention with powers to consult and confer upon the expediency of limiting the prices of articles of produce and merchandise. The letter of instruction addressed to the delegates, while admitting the many advantages to be gained from the general limitation of prices, was, on the whole, devoted to a powerful rehearsal of the arguments against such a proceeding. The Convention met on Saturday, the twenty-ninth of January, 1780, all the States concerned being represented except New York and Virginia.215 The absence of these States prevented action, except that a Committee was proposed to be appointed to prepare a plan for the limitation of prices to be submitted to the Convention at an adjourned meeting. Letters were sent to New York and Virginia and the Convention adjourned to meet in Philadelphia April fourth.

Before that date arrived Congress on the eighteenth of March, 1780, by Resolve declared that the Continental bills then in circulation were not worth more than one fortieth of their denominational value.216 They recommended the States to call in and destroy their several quotas of the bills in circulation and to issue new interest bearing State bills, payable on short terms in gold and silver, which bills the United States would guarantee. On the fifth of May, 1780, Massachusetts complied with this request, called in her share of Continental bills and provided that collectors might receive gold or silver in payment for the taxes through which this was to be accomplished on the basis of one to forty. It is evident that from the time that Congress openly discredited these bills in March, 1780, there was no more need of efforts to sustain the currency whether by plans for limiting prices or by other means. Prices would now take care of themselves and be governed by natural laws.

The schedule of prices adopted by the town of Hingham is an event of minor importance in this episode which convulsed the whole country during the period of the currency inflation from 1776 to 1780. Such documents are however well worth preserving, and they will serve their purpose if a perusal of them causes us to stop and reflect upon the curious state of affairs which their very phraseology betrays. We have seen that in Massachusetts surveillance and inquisition was brought to bear to prevent the acquisition of gain by dealers in goods and provisions; that neighbors were urged to watch one another in order to prevent undue advantage on the part of individuals; that towns abused towns and States passed protective laws directed against neighboring States. Will our legislation of to-day read as strangely to the student of history a century and a quarter hence? Will Boston Gas and Standard Oil and Northern Securities and Labor legislation seem as strange to him as these attempts to regulate prices seem to us to-day?217

The following memoranda disclose the name of the editor of the Letters and Other Writings of James Madison, Philadelphia, 1865, which has hitherto been sought by bibliographers without avail.

There have been published two collections of Madison papers. The first, consisting of the report of the debates in the Constitutional Convention of 1787, was drawn up from the manuscripts purchased by Congress in 1837 from Mrs. Madison at the cost of $30,000. This publication consisted of three volumes and was printed at Washington in 1840 and reproduced at New York in 1841. The publication with which we are now concerned was drawn up from manuscripts purchased by Congress in 1848 from Mrs. Madison at the cost of $25,000. Congress in 1856 appropriated $6000 for the publication of 1000 copies of these papers, but in 1865 (as will appear more fully in the report below) reduced the number to be printed to 500.

In addition, I give some extracts from the Records of the Joint Committee on the Library which give details regarding the progress of the publication and show that William Cabell Rives had some of the manuscripts in his possession from 1856 to 1866.

I am indebted to Senator George Peabody Wetmore, Chairman of the Committee on the Library, for permission to take down these notes.

In 1859 Rives published the first volume of his Life of Madison. In the preface he says that —

Many valuable and authentic materials for such a work having recently come into the hands of the writer by a public charge confided to him, and others being placed at his disposal by private courtesy, he was led to consider it a duty, so far as his other occupations would permit, to attempt the execution of a task, which surmises without foundation represented him to have entered upon, at a much earlier period.

Seven years intervened between the publication of the first and second volumes of the Life of Madison. The preface to the second volume states that —

It was prepared for the press more than four years ago, in the state in which it is here given, but, prevented from publication by the inauspicious circumstances of the times, is now submitted to the judgment of the reader.

The Records of the Joint Committee on the Library, now to be quoted, show therefore that a portion of the manuscripts were in Rives’s possession as late as 1866, he having had them throughout the period of the Civil War, in which he took part on the Confederate side.

On 27 January, 1865, the Joint Committee on the Library of Congress made the report here printed. This report was never issued as a document, but appeal’s in the proceedings as printed in the Congressional Globe. This probably accounts for its not having been previously discovered.

Mr. COLLAMER. The Committee on the Library have directed me to report a joint resolution in relation to the publication of the papers of James Madison, and I wish to have the unanimous consent of the Senate to consider the joint resolution at the present time. I will state the situation of the case. Congress passed an act directing the Committee on the Library to publish the correspondence of James Madison, and appropriated, I think, $8,000 for the purpose. They were to publish one thousand copies, which would be four thousand volumes, as the work is to be in four volumes. The committee entered into a contract under the law. In the first place they employed Mr. Rives, of Virginia, to make the compilation, and the papers which had been purchased of Mrs. Madison some years before were put into the hands of Mr. Rives to make that compilation. He did make the compilation and returned the copy here, and was paid for his work out of that appropriation $3,000. After the copy was furnished by Mr. Rives, a contract was entered into with Mr. Wendell to make the publication, and Mr. Wendall, of this city, was appointed to prepare the index for the work and to supervise the proof-sheets. The thing went on; but the change of circumstances, the increase of prices, &c, disturbed it, so that at last Mr. Wendell failed altogether; he could not perform the work, and he gave up the contract. We find that we cannot get the work published to the amount of one thousand copies or four thousand volumes for the money in hand; but we are of opinion that five hundred copies, two thousand volumes, will be sufficient to enable Congress to make all the distribution and exchanges that have been made of the works of Mr. Hamilton, and we can probably make a contract securing the publication of that number of copies for the money already on hand at the present rate of materials and labor. The committee are of opinion that it is advisable to finish it, and to receive the five hundred copies instead of one thousand as originally provided by law. This resolution is to carry that idea into effect by authorizing the committee to contract for five hundred copies instead of one thousand.218

The following extracts are from the Records of the Committee on the Library of Congress:

1856, August 27. The Chairman of the Committee was authorized to engage W. C. Rives to edit the Madison papers.

1860, February 14. The manuscripts of the Madison papers as edited by the Hon. W. C. Rives of Virginia were received and arrangements for the printing of 1000 copies were considered.

1860, May 28. A proposal from C. Wendell to print and bind 1000 copies of the Madison papers was considered.

June 11. It was voted that if an appropriation of $2000 in the Civil Bill passed the House, the Chairman of the Library committee be authorized to contract with C. Wendell for the publication of the Madison papers at 95 cents per volume of 600 pages, and that the Chairman be also authorized to contract with P. R. Fendall, Esq., to index and revise the proof-sheets of the same at $800.

December. F. D. Stuart was employed to copy from Freneau’s Gazette the articles by Madison for publication in the Madison papers.

1866, January 17. It was voted that the Hon. W. C. Rives be addressed by the Chairman of the Committee with a request that he will return all of the original papers of James Madison in his possession to the State Department.

1866, February 12. The claim of Philip R. Fendall for compensation on account of labor performed in indexing and editing the writings of James Madison was considered, and it was voted that the deficiency bill be amended to include an appropriation of $2100 to make up the full compensation of $3000, due Mr. Fendall.

The Records of the Joint Committee on the Library also contain various other items regarding the Madison papers, as for example, that the papers of Helvetius be included in the publication; or, for example, that the Librarian of Congress be directed to draw up a list of libraries which should receive the printed volumes.

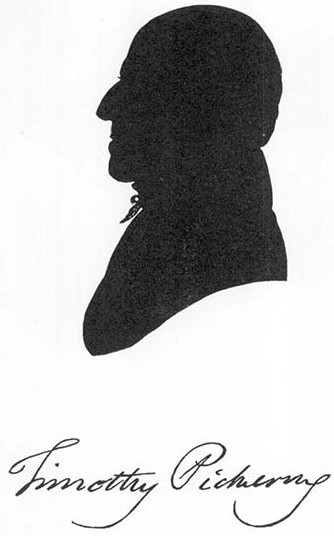

On behalf of Dr. Horace Howard Furness, a Corresponding Member, Mr. Henry H. Edes presented a silhouette of Timothy Pickering.

Mr. Edes remarked that on the margin of the portrait was an embossed stamp, — “Bache’s Patent,” — and the following words written partly in pencil and partly in ink: “T. Pickering Sec. State to Washington, for Mr Jenks.” Pickering’s sister, Lucia Pickering, married Israel Dodge 17 June, 1766. Their son Pickering Dodge married Rebecca Jenks, daughter of Daniel and Mary (Masury) Jenks, 5 November, 1801, and had a daughter, Mary Jenks Dodge, who married 24 March, 1831, George Washington Jenks, — the person to whom this silhouette once belonged. He was a son of John and Annis (Pulling) Jenks, born 13 June, 1804, a merchant, and died at St. Louis, Missouri, 12 August, 1867. His sister, Annis Pulling Jenks, born 13 October, 1802, married 25 August, 1825, the Rev. William Henry Furness (H. C. 1820), the father of Dr. Furness.219

Mr. Albert Matthews remarked that, when recently shown this silhouette, he recalled a passage from Pickering’s writings and also a skit entitled All Tories Together, which he had stumbled on in a Philadelphia newspaper. These follow.

I

I have long entertained the opinion, that the few men who for the last twelve years have moved all the springs of public action . . . intended to involve it [our country] in a war with Great Britain; . . . For to the passions and prejudices of the people in favor of the French and against the English, which those men have zealously and perseveringly excited and cherished, they are deeply indebted for the power now in their hands. This is so true, that for many years past their partisans have deemed it sufficient, to ruin any man in the eyes of the People, to pronounce him a friend to Great-Britain; or, in their language of vulgar abuse, a British Tory.220

II

ALL TORIES TOGETHER.

FROM THE PHENIX.

Oh! come in true jacobin trim,

With birds of the same color’d feather,

Bring your plots and intrigues, uncle Tim,

And let’s all be tories together.

Bring the heart chilling tales of last war,

Told by each refugee you can gather;

Bring the father of Christopher G ***221—

Let us all be rank tories together.

We’ll talk about Lexington fight —

How you pray’d for success and fair weather,

While your friends were effecting their flight —

And let’s all be tories together.

And of Robinson’s222 proofs all so dread,

Of conspiracies, hatched in a cellar;

That frightened poor granny Morse dead —

And let’s all be tories together.

Let us fill up the newspapers with stuff;

With addresses and pamphlets so clever;

And swear there’ll be taxes enough,

To make us all tories together.

Let’s tell horrible tales of black Sail,223

And of babies curl’d headed and yellow;

All that malice can dictate we’ll tell,

And we’ll all be tories together.

Let us mourn for the days that are pass’d,

In the lap of Great Britain, our mother,

In joys too delicious to last —

But still let us be tories together.

And I charge you, my dear uncle Tim,

If England wants help, that you tell her,

We’ll stick to her cause, sink or swim,

Like hell hounds and tories together.224

Mr. Matthews also communicated a Check-List of Boston Newspapers from 1704 to 1780, and spoke as follows:

Historical and other students who have occasion to consult American newspapers of the Colonial period have great difficulty in ascertaining where such papers are to be found. No library known to me has a proper catalogue of the papers in its possession, and there does not seem to be in any library a person who knows what it contains. Consequently, much time is wasted in a search for a particular paper. In July, 1903, there was placed in the Boston Athenæum a manuscript Check-List of Boston Newspapers from 1704 to 1760. This was compiled by Miss Mary F. Ayer of Boston, and located every known issue of every Boston paper in eleven libraries. As a labor-saving device, this list deserves to be printed. The matter was brought before the Council at its meeting in February last, when it was —

Voted, That the Committee of Publication are hereby authorized to print this Index in the Publications of the Society, provided Miss Ayer will continue it to 1780,— the period of the adoption of the Constitution.

Miss Ayer, on being approached in the matter, very willingly undertook to carry out the wishes of the Council, and has even increased our obligations by adding another library (that of the Bostonian Society) to her list. The twelve libraries catalogued by Miss Ayer are as follows: American Antiquarian Society, Boston Athenæum, Boston Public Library, Bostonian Society, Essex Institute, Lenox Library, Library of Congress, Library of Harvard College, Massachusetts Historical Society, Massachusetts State Library, New England Historic Genealogical Society, State Historical Society of Wisconsin.225 Miss Ayer has also indicated issues which are mutilated, those which lack the Supplement, those which have the Supplement only, and duplicates.

It gives me pleasure to communicate to-day the list compiled by Miss Ayer, and I beg to offer the following motion:

Voted, That the thanks of The Colonial Society of Massachusetts be extended to Miss Mary Farwell Ayer for completing, at the request of the Council, her laborious and valuable Check-List of Boston Newspapers from 1704 to 1780, and for presenting it to the Society to be printed in its Publications.

This vote was unanimously adopted.

Mr. Frederick L. Gat communicated by title: (1) Instructions from Cromwell, in 1654, to the Governors of Massachusetts, Plymouth, and Connecticut, to aid Major Robert Sedgwick in an intended attack on the Dutch at Manhattan; (2) Papers relating to the capture by Sedgwick in 1654 of Port Royal and Penobscot; (3) Two letters written by Sedgwick at Jamaica in 1655 and 1656; and (4) Three letters from Jamaica relating to the same expedition.

The name of Mr. Appleton Prentiss Clark Griffin. was transferred from the Roll of Resident Members to that of Corresponding Members, since he has removed his permanent residence from Massachusetts to Washington, D. C.

Comt.

Comt.

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly

Committee

Committee