MARCH MEETING, 1905.

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held at No. 25 Beacon Street, Boston, on Thursday, 23 March, 1905, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the President, George Lyman Kittredge, LL.D., in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

The Corresponding Secretary reported that letters had been received from Mr. Francis Henry Lee of Salem, and Mr. Horace Everett Ware of Milton, accepting Resident Membership, and from Mr. Clarence Winthrop Bowen of New York, accepting Corresponding Membership.

The Corresponding Secretary also reported some valuable gifts of books from Dr. Daniel C. Gilman, a Corresponding Member, which were gratefully accepted.

The subject of permanent quarters for the Society was discussed and referred to the Council for consideration.

Mr. John Noble read extracts from advance sheets of the third and last volume of the Records of the Court of Assistants, which will cover the period 1642–1673. The volume will comprise restored fragments of the records,119 the original book or books having long since disappeared. These fragments, consisting of certified copies of portions of the records culled from Court files of the older Counties of Massachusetts and from the Archives of Massachusetts and other States, cover a wide range of subjects,—judicial, historical, and antiquarian, — and are also of great practical value, having been cited and used effectively in litigation in the Counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, and Bristol. One subject of great interest included in the volume is the ownership and title of Nahant.

Mr. Andrew McFarland Davis read the following paper on —

CURIOUS FEATURES OF SOME OF THE EARLY NOTES OR BILLS USED AS A CIRCULATING MEDIUM IN MASSACHUSETTS.

The first attempt, after the days of barter were over, to furnish a substitute for coin as a medium of trade in Massachusetts, which has left a well-defined trace behind it, was made in 1681. The projector of the Company through which this was accomplished, who was identified by Mr. Trumbull120 as the Rev. John Wood-bridge, asserts that his attention was attracted to the subject as early as 1649 by Potter, the author of the Key to Wealth, and that in 1671 an experiment was carried on in private which was stopped “when bills were just to be issued forth.”121 Then came the establishment in the fall of 1681 of “The Fund at Boston in New England,” an association of Boston merchants, organized for the purpose of mutually adjusting their debts, through Credits in the Fund, based upon Mortgages of Lands or deposits of goods.122 A few months’ trial seems to have favorably impressed the associates, and Woodbridge was then employed to write a prospectus of the Company which should be an explanation of its purposes and an appeal to the public for approval and support. “Severals relating to the Fund,”123 a publication which appeared in the spring of 1682 and of which a single copy has been preserved, was the result. If the quaint obscurity of the phraseology of this work makes the text of the pamphlet difficult to understand for one accustomed to modern methods of expression, and if we admit that such a document issued for a similar purpose to-day would be worse than useless, we must in justice to the author, in making an estimate of its contemporary value as a prospectus, take into consideration the different style of composition in use at that day. In any event, we must be grateful to him for having preserved for us a description of the Fund and its methods, which without serious effort is capable of interpretation.

“Credit” was the underlying idea of the Fund, and the security of the “deposit in Land, real, dureable & of secure value” was evidently preferred to what was then termed the “Merchandise Lumber.”124 The associates severally established individual credits there, which were interchangeable on the books of the Company in the adjustment of debts between themselves. The credits could indeed be made use of with outsiders if they were willing to accept payment in Fund Credit. All persons receiving payment in this way were termed “Acceptors of Credit.” The transaction above described was in its general features similar to the method in which Bank Credits in the Bank of Amsterdam were made use of, where, for a time at least, transfers could only be made at the counter of the Bank. The rules of the Fund, however, contemplated the availability of Fund Credit elsewhere than at the office of the Fund, and provided for this through what were termed Pass-Bills and Change-Bills. The former were in substance checks and the latter operated somewhat as does the modern letter of credit. Each Change-Bill was a certificate that the owner had a certain credit in the Fund. The Fundor to whom the owner offered it in settlement of debts endorsed on it the amount required to be transferred to his credit for the adjustment of his debt, precisely as the Banker making an advance on a letter of credit endorses the amount advanced thereon. The details to be observed in making such endorsements were specifically set forth in the rules of the Fund. When, in the process of making a payment, the credit on the Change-Bill was used up, the acceptor of credit applying the unappropriated balance remaining thereon was to take it up and return it to the office of the Fund.

It will be seen from the above that the projector of the Fund had not conceived of a denominational paper currency as a substitute for coin. He was working only with Bank Credit.

We have no direct testimony as to the success or failure of the Fund, but we may infer that it was successful from the following facts. A short time before this, apparently in 1667 or 1668,125 Woodbridge had appeared before the Council of the Colony and advocated his theory, but without securing any expression of approval. In the records of the Council during Dudley’s administration,126 under date of the twenty-seventh of September, 1686, it appears that the proposal of one Blackwell for erecting a Bank of Credit was received and read. If we may credit a document in the Archives, Blackwell’s proposal had been before the Council in June of that year,127 and had been referred to the Grand and Standing Committee, a body which had for its special function the consideration of the encouragement of Trade and Commerce. It was apparently the report made as a consequence of this reference which was before the Council on the twenty-seventh of September. In this report the Committee expressed their approval of the Scheme in direct and forcible language.128 The report was accepted by the Council and the countenance of his Majesty’s authority, respect, and assistance was pledged to the enterprise. Favored thus by the government, Captain John Blackwell, the projector, proceeded to organize his Bank,129 which, like the Fund, was based upon the idea of granting credits upon Land Security. Unfortunately for our purposes the experiment did not proceed beyond this stage, and I dwell upon it thus long only because it is evident from the language used in contemporary documents that the projectors of the bank contemplated the emission of bills of Credit which should serve as a circulating medium, primarily between subscribers to the Articles of Agreement, ultimately with the public, the twenty shillings bill being the minimum to be issued. It would be interesting to examine the form of bill which was proposed to be emitted, but unfortunately neither the documents in the Archives nor the prospectus of the Bank gives the slightest hint of its contents. We may be sure that it was better adapted for circulation than the “change-bill” of the Fund, otherwise the projectors could hardly have expected it to circulate freely with the public.

The Fund was organized in 1681 and traces of credits taken out are to be found in the Registry of Deeds, in the records made during the summer of 1682.130 Blackwell’s Bank was organized in 1686 and preparations for work continued in 1687. In 1688 it was spoken of as a thing of the past. In 1690 came the first emission of Colony Bills, in which the phraseology was such that they were perfectly adapted for circulation as a medium of trade. Each bill was in form a due bill of the goverment, in which it was stated that it would be in value equal to money, and would be received at the Treasury in all payments. It was prescribed in the Act of Emission that the bills should be indented, and for many years the plates were so prepared that a stub was printed simultaneously with the bill, which, after the bills were separated from it, could be preserved, thus keeping on file a complete set of the indents.131 The form then adopted practically served for use for all the subsequent emissions down to 1749. In one of the later emissions, it was specified that certain taxes were not to be paid in the bills of that emission. The indent was abandoned in 1737 in the bills of new tenor, and a value was then stated in silver or gold; the former being accomplished so far as the phraseology of the bill was concerned by dropping the word “Indented,” and the latter by substituting the specie value for the word “Money.” The skeleton of the form remained, however, the same.

In 1714 certain Boston Merchants, under the plea that there was “a sensible decay of Trade” “for want of a Medium of Exchange,” proposed to establish a Land Bank upon the lines of the projected Bank of 1686. The Scheme met with violent opposition on the part of the government and was frustrated, but from the pamphlet entitled “A projection for erecting a Bank of Credit,” which the projectors published, we can ascertain what they then conceived was a suitable form for a note or bill to circulate as money.132 It was simply an obligation based upon the Articles of Agreement of the Society, compelling subscribers to receive the bill in lieu of money and the Company to receive it in the Bank.

In 1732 certain merchants in New London, Connecticut, secured a charter and organized a bank along the same lines as Blackwell’s Bank and the Land Bank of 1714. Although this was not a Massachusetts venture, still the fact that their organization was based upon a Massachusetts prototype will bring their Company within the scope of our theme. They proposed to emit bills secured by mortgages of real estate or pledges of personal property, given to the Society which was called The New London Society United for Trade and Commerce. The form of bill which they adopted resembled the bills of public credit then in use, being practically a due bill to be accepted by the Treasurer of the Society and in all payments in said Society from time to time; that is to say, in all payments among members of the Society. It differed from the bills of public credit in describing the value of the bill as being “equal to silver at sixteen shillings per ounce, or to Bills of this or neighboring governments,” instead of merely stating that it was “equal to money.” It will be recognized that in the clause fixing the silver value of the note, the new tenor bill of 1737 was anticipated. This Society133 met with an untimely fate, for as soon as the Governor of Connecticut heard that it had actually begun to circulate its notes he called an extra session of the Assembly, at which the Charter was abrogated and steps taken to compel the retirement of the notes.

In 1733 about one hundred Boston merchants formed a company and proceeded to emit what they termed “bills or notes of hand,” which were intended for circulation in Massachusetts. Before describing these notes of hand, which are generally known as the “Merchants’ Notes of 1733,”134 it is desirable, perhaps essential, that a statement should be made showing why these Boston merchants intervened and added to the paper currency in circulation, which was already inflated to danger point.

For some time the Privy Council had exerted its utmost endeavor to secure a reduction of the annual emissions of currency in the several Colonies. At this time Belcher was at the head of affairs in Massachusetts and in New Hampshire. He was disposed to follow literally all the Royal Instructions and so far especially as those were concerned which compelled a reduction of the paper-currency in circulation, he was evidently in full sympathy with their import. It was known, therefore, that in these two Provinces there would be, unless the Instructions should be changed, a steady reduction of the bills of public credit for the next eight years, after which only a limited amount could be annually emitted.

Connecticut and Rhode Island were not administered by royally appointed governors, and Royal Instructions were not enforced there with the same strictness that they were in Massachusetts.

The process of curtailment of the circulating medium actually begun and the threat of future continuance produced dismay in the provinces where the Royal orders were being enforced, but in Rhode Island there was no such feeling. For some years this Colony had been in the habit of loaning large sums of currency to citizens at low rates of interest, thus deriving aid in support of the government from the emissions, while the borrowers were in turn able to secure a profit by loaning the bills at current interest in Massachusetts, where they found ready circulation. The impending reduction of the volume of currency in Massachusetts furnished opportunity for another of these “Banks,” as these emissions made with intent to loan were termed. If the bills of this new emission could be disposed of in Boston, the merchants and traders there would be compelled to undergo the hardships involved in the contraction of their own bills of public credit, while the amount of currency actually in circulation would be maintained at its full height in bills which they believed were not of equal value with those of the Massachusetts emission. How could this be prevented?

The first and most natural suggestion was a boycott, in which, when it was proposed, the merchants found ready sympathy from the community. The second suggestion was to supply the void in the circulating medium caused by the retirement of the bills of public credit through the emission of notes of their own, and it is evident that they hoped by means of these notes to bring about a return to a specie basis. Each note135 then put forth was signed by five merchants, the ten directors of the Company being divided into two groups for that purpose, thus giving to the possessor the joint and several promise of five respectable persons for the payment of a specific sum of silver or its equivalent in gold, at certain fixed future dates. The normal or par quotation for silver in terms of New England currency was frequently spoken of as seven shillings an ounce. It was based upon a sterling value of five shillings two pence per ounce which actually gives, on the basis of 133 for 100, a fraction less than six shillings eleven pence pei ounce. The current rate at that time in currency was about nineteen shillings per ounce, and the valuations given in the notes emitted by the merchants were on that basis. Each note was made payable in three instalments, covering ten years; the first falling due December thirtieth, 1736, when three tenths would be paid; the second December thirtieth, 1739, when a second three tenths were payable; and the balance December thirtieth, 1743. Moreover, it was specifically provided in the bills that upon the payment of the instalments in 1736 and 1739, the notes should be renewed. If we consider that the total emission was £110,000 in denominational values adapted for circulation we can imagine the task set for these gentlemen in 1736 and 1739, when they should pay these instalments, take up the notes, and supply the possessors with new notes for the unredeemed fraction. It is not probable, however, that they ever experienced any serious trouble in this direction as the price of silver rose rapidly shortly after the emission, and the notes having a promise of redemption at a fixed value disappeared from the market and were hoarded.

The suggestion that these notes were emitted in the hope that they might contribute in leading up to a resumption of specie payments is based upon two things, first, the features of the notes themselves, and, second, the similarity of these features to some of the efforts in this direction which were put forth for many years about this time by the hard money men.

If we examine the note we shall find that the projectors did not attempt to force their currency at a rate above that at which the bills of public credit were circulating. They accepted the current rate of silver and they evidently conceived that the addition of their emission to the bills in circulation would not disturb that rate. In this they were mistaken. The merchants’ notes, when combined with the Rhode Island notes, which after a short time freely circulated in spite of the boycott, so greatly increased the volume of currency as to send silver up to twenty-seven shillings. Thus the disasters impending from the Rhode Island notes were not only realized, but the merchants’ notes were, to a certain extent, contributory. Nevertheless, it is possible to conjecture the expectations of the merchants. If their notes had quietly floated on the market at the current rate of silver, and the redemptions had taken place at the end of three, six, and ten years, £110,000 in coin would have been put in the hands of the public, and it would have been an easy matter to have secured enough more to have resumed specie payments. This proposition involved the belief that the silver put out in the partial redemptions would have staid in circulation. The scheme would probably have been wrecked upon that reef if disaster had not previously occurred.

That it was then believed that resumption could be approached by successive steps in the manner proposed by the Boston merchants is shown by a Scheme proposed in 1734 for emitting bills of public credit which were to be loaned for ten years to borrowers who were to repay their loans in annual payments in silver. The bills to be emitted were declared to be in value equal to silver coin and were to be redeemable, one half of the face of the bill in five years in silver, and the other half at the end of ten years in silver. When the first instalment should be paid the bill was to be surrendered and a new bill for the balance was to be issued.136

This was merely a piece of abortive legislation, and at best it was but a proposition which could never have been realized, but it shows a tendency of thought.

The action of the merchants of New London and Boston stimulated the business men in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1734 to organize a Company for the purpose of supplying the local community with a circulating medium composed of the notes or obligations of the subscribers to the Articles of the Company. These notes were dated December twenty-fifth, 1734; were signed by three Portsmouth merchants and contained their joint and several promise to pay the face value of the notes in twelve years, in silver or gold at whatever rate they might then be quoted, or in passable bills of credit of the New England governments, with interest at the rate of one per cent per annum.137

A statute was passed April eighteenth, 1735, in Massachusetts prohibiting the passage of these bills in that Province.138 In the preamble to this Act the notes are described as “payable in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island bills, or in silver, gold or hemp at the unknown price they may be, at Portsmouth, in New Hampshire, anno 1747.” Belcher, then Governor of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, called the scheme the “hemp bank” and said it would be but a “bank of wind.” From this it is plain that the merchants must originally have contemplated the payment of their bills in hemp as well as coin and currency. The notes met with but a feeble support from the community and only an occasional specimen has survived, but we do not find that any of them are payable in hemp.139

In 1737 there was a new form adopted for the bill of public credit, the most important feature of which, viz. the change of the phrase “shall be in value equal to money” to “shall be in value equal to so much silver or so much gold,” has been already referred to.140

These new tenor bills were made by law receivable at the Treasury at first on the basis of one for three of the old tenor bills and in later emissions on the basis of one for four. Inasmuch as all the bills were subject to retirement through taxation, the ultimate destination of the bills was the Treasury, hence, by means of the legislation establishing this discrimination against the bills of the old tenor at the Treasury, the circulation of the new bills was maintained substantially according to the terms of the Acts. The ounce of silver at the rate of six shillings eight pence was the unit on which, in fractions or multiples, the denominational values of the first new tenor bills were determined, the rate per ounce adopted being as a matter of fact one that had not prevailed in the Colony for many years. “It is one of the enigmas of the history,” says Professor Sumner, speaking of the simultaneous recognition of the Spanish dollar at six shillings and of this silver valuation, “that the Colonists treated this rate and 6s 8d per ounce” as equivalent.141

Allusion has already been made to the curtailment of the currency, or rather to the reduction of the amount annually emitted by Massachusetts and New Hampshire, which resulted from Belcher’s enforcement of the Royal Instructions. As the time limit set for the withdrawal of the bills in circulation approached, and as the period came close at hand when the Province would have to be content with an annual emission of currency which, even at par, would have been inadequate for the needs of the government, there was much restlessness and uneasiness throughout the Province. Men of speculative temperament began to ask why they should not form a Company on the lines of some of the former projections and emit bills. As a result of this discussion a Company was formed — afterward known as the Land Bank and Manufactory Company, which promulgated a scheme, secured many subscribers to it, and in the summer of 1740 petitioned the Assembly for a charter. It is not my intention to repeat at this time the story of the Land Bank of 1740. I have already narrated it to this Society,142 but in the prosecution of the topic of this paper, I must now deal with the peculiar features of the note which they proposed to, as well as of those which they actually did, emit. In March, 1740, the projectors published a broadside in which they incorporated the form of the intended note or bill of credit. It was a promise of the signers for themselves and their partners, to receive the bill of credit of the Company as so much lawful money. The bill was to run for twenty years and was then payable in manufactures of the Province.143

It has been seen that in the case of the New Hampshire merchants’ notes there was an undoubted difference between the note suggested in the Scheme and the note actually emitted. So also in regard to the Land Bank of 1740, the notes of that Company which have come down to us, while they retain the more important of the peculiarities of the note proposed in the original Scheme, were altered in one respect and that, perhaps, an important one. They were still the promise of the signers for themselves and their partners to accept the notes in all payments; they were still to run for twenty years and they were to be paid then in produce or manufactures, but instead of the bill actually emitted containing the promise that it should be received by the subscribers as so much “lawful money,” it was to be received as “lawful Money at Six Shillings & Eight Pence ⅌ Ounce.”144 If by lawful money the projectors meant in the broadside to put their notes on a par with Spanish coined silver which was practically the meaning of the phrase “lawful money” prior to the emission of the new tenor notes, then the change was not of much importance. It is true that the definition of lawful money to be evolved from the earlier provincial legislation, viz. “silver on the basis of six shillings for the Spanish dollar of seventeen pennyweights,” was then considered to be equivalent to silver at six shillings eight pence per ounce, but, to quote Professor Sumner again, it is one of the enigmas of the times that the writers and legislators of the time evidently so regarded it. Whatever may have been the intention of those who drafted the original form of the note, it is evident that the amended form was intended to remove all doubts as to the meaning of “lawful money,” which was accomplished by stating a specific silver value. The notes were put forth at a rate evidently intended for par in silver at a time when the quotation was twenty-eight shillings to twenty-nine shillings an ounce, or, as we should say, specie was worth about 400. For their security there were mortgages of lands and pledges of goods running in favor of the Company and not specifically protecting any particular notes. Granting that the silver value should prove acceptable to the community, the notes still had to fight their way into circulation burdened with a redemption clause distant twenty years and the holder had facing him when he should demand payment the possibility of receiving cast iron, bayberry wax, tanned leather, cord wood, oil or a variety of other articles equally unsuitable for daily use in the way of a medium of trade. Nevertheless the notes found circulation, the Scheme was popular and the capitalists of Boston were put to it to devise some method of opposing it.

One of the means adopted was the boycott; and in this case it was much more effective than it had proved with the Rhode Island bills in 1733. The inherent weakness of the Land Bank would in any event have made prudent capitalists cautious how they received the bills even without any agreement to reject them. Their natural avenue of circulation was in the small towns and among the poorer classes.

But, while the capitalists of Boston condemned the bills of the Land Bank, they did not abstractly condemn all attempts to relieve by means of a paper currency the impending need for a circulating medium caused by the proposed withdrawal of the Province bills. On the contrary, they organized a company of their own for this purpose. Regarding it as absolutely “impracticable so suddenly to procure Silver and Gold sufficient for the management of our Trade and Commerce,” as they stated in their Scheme, they proposed to emit their own notes to be redeemed in coined silver of sterling alloy at twenty shillings per ounce by the last of December, 1755.145

The organization which these gentlemen established was known as the Silver Scheme or Silver Bank. There were ten directors and these directors were authorized to sign the bills. The bill which was emitted was very simple in form and consisted solely in the joint and several promise of the signers to pay to the order of Isaac Winslow, merchant, so much silver sterling alloy, or the same value in gold by December thirty-first, 1755, the equivalent denominational value expressed upon the bill being based upon silver at twenty shillings. The current rate of silver in the fall of 1740, when the bills were emitted, was between twenty-eight and twenty-nine shillings. It was agreed that for the first year possessors could redeem the bills at the rate of twenty-eight shillings four pence per ounce; the second year at the rate of twenty-seven shillings nine pence per ounce, and so on at a reduction of seven pence per ounce each year, which would bring the rate of the fifteenth year, when the bills were to be redeemed in silver, to twenty shillings, the same as that in which the denominational values were expressed in the bill.

It will be seen that, if the value of silver had remained the same during these fifteen years, the possessor of one of these bills would have reaped a benefit through the annual appreciation of the silver rate nearly the equivalent of an annual three per cent interest rate.

The Silver Bank and the Land Bank both sought incorporation and, failing that, both proceeded to emit bills. Both were closed through Parliamentary action in 1741.

Their example and particularly the example of the Land Bank, led to attempts to organize companies of this sort outside Boston. One of the Land Banks thus organized actually emitted bills for circulation. The company in question was founded in Ipswich in 1741. Its career was brief and inconspicuous. The bill emitted by the Company was the joint and several promise of those who signed it, for themselves and for their partners, to take the bill at its denominational value, as so much lawful silver money, at six shillings and eight pence per ounce, in their own trade and for stock in the Company’s hands. It was payable on demand in the produce or manufactures enumerated in their scheme, which was said to be on file in the Records of Essex County.

Diligent search has failed to reveal this Scheme, but the resemblance of the bill to that of the Land Bank of 1740, would indicate that the list resembled that enumerated in the Manufactory Scheme. The most important difference between the two bills was that the Ipswich bill was payable on demand.146 The Company, however, did not get started until the enforcement of the Parliamentary Act directed against such banks had been set in motion.

In January, 1742, an entirely new set of plates was prepared for the bills of public credit, the engraving of which was of the highest order of skill and the form made use of was also new. The system prevailing in the last previous set of basing the denominational values upon the ounce of silver at six shillings eight pence was abandoned, although each bill was declared to be equal to a specified weight of coined silver which was based upon that rate. The bill was in the old form of a due bill and was to be “accepted in all payments and at the Treasury.”147 In other words, the legal tender function was given it and there was no discrimination against it in any of the taxes at the Treasury, as was the case with the first new tenor bills. In the Act authorizing this emission148 it was ordered that in settling sterling grants to be paid out of the supply made by the Act, five shillings and two pence sterling should be paid with six shillings and eight pence of the bills then issued, a conversion which was, as has already been pointed out, absolutely irreconcilable with the theories of the two currencies.

In June, 1744, a new form of bill, the last made use of by the Provincial Assembly, was adopted. It was still a due bill and the value was still given in a specified weight of silver, but the rate of six shillings and eight pence per ounce was abandoned and seven shillings and six pence per ounce substituted. The bills were no longer required to be “accepted in all payments” but were simply to be “accepted in all payments in the Treasury.”149

With this third form of the new tenor bill our subject concludes. As we run through the various forms of bills of public credit, emitted or proposed to be emitted, we note that all of them are modelled after the Colony bill, while among the bills emitted by private companies there are several which are promises to pay. As a matter of fact, there was but one instance in which it was proposed to the government that the form should be changed from the due bill to the promise to pay and in that particular case but scant consideration was given to the proposition which was submitted.150

The development of the topic under consideration has not involved new investigation or original research, but the collation of these notes will facilitate the study of their peculiarities. In order to present, side by side, the forms of the several notes, it has been necessary to omit comment upon the career of the several companies, except such as was essential for an understanding of the notes themselves. Perhaps it would have been better if even this had been omitted.

Mr. Lindsay Swift read a paper on the truth in history, speaking in substance as follows:

Last December I offered a short paper on John Davenport’s Election Sermon of 1669, and I then supposed that I had properly covered the main facts of his career so far as it was related to this sermon;151 but when I came to prepare the paper for the press, I was mortified to find that I had narrowly escaped missing the whole point. The late Hamilton A. Hill’s History of the Old South Church told me certain most relevant facts which had been, shall I say deliberately, ignored by previous writers who had touched on Davenport’s career. I do not intend to reopen the subject now, but it has furnished me with a small text on a large matter, — and since, at Mr. Edes’s amiable solicitations, I have agreed to say something at this meeting, I shall venture a few observations which from my own point of view have a practical bearing for us as students of history, and which are the results of experience, partly as an officer in the Boston Public Library, and partly as a reader of books. It will not be strange if these observations appear to be scattered and inconclusive; for I do not see how in so brief a consideration they can very well be otherwise.

It would be fair to divide roughly the various suppressions of historical truth into two classes: one is deliberate and conscious, — the result of natural caution or timorousness; the other is unconscious and temperamental, and displays itself through the writer’s method of treating his subject. This is the more deep seated and delusive of the two.

The deliberate suppressio veri (such as I have instanced in the case of John Davenport and his curious manæuvrings on his leaving the church at New Haven and accepting the pastorate of the First Church in Boston) expresses itself in many ways, but caution, due to social and personal reasons, is at the bottom of most of it. We, of New England, have at times been accused of treading with considerable care over some uncomfortable places in our historical past, and it is very natural that this should be so, for the bright and sombre parts of our story are closely related and interwoven, and much sensitiveness prevails. It is really difficult to stop at the right moment in telling some truths.

A few months ago an acquaintance, known to me through my position in the Public Library, told me that he, with another person, was writing a novel of our Revolutionary times, and wanted a “suggestion.” I told this seeker after “materials to serve,” that the character of John Hancock seemed to me an inviting one from the novelist’s point of view, and referred him to the recently-printed letters of William Bant,152 who was a sort of factor or henchman to Hancock. The book was published a short time ago, and over its trivial pages has raged quite a little journalistic battle in the Saturday issues of the New York Times, begun by a Boston contributor who felt deeply aggrieved at any aspersions on our patriotic Governor. I was urged to take part in this fray, but decided that my disclosure of the Bant letters was a sufficiently generous contribution. The matter is relatively unimportant, but the controversy does suggest a question which each of us has doubtless asked himself, as to how far we may properly go in historical narration, especially as regards the use of gossip, scandal, and trivial and unrelated anecdote. I think a fairly safe working rule will be followed, if we introduce unpleasant and even unsavory facts only when they are contributory to the general framework of biography and history, but not when mere scandal-mongering serves to hide the greater truth. I think, for instance, that we may arrive at a better understanding of the comprehensive genius of Franklin, — a genius not easy to interpret, in spite of its apparent simplicity and unpretentiousness, — if we know that a son and grandson were born out of wedlock, and that the latter, a rather formal and priggish character, also left spurious progeny. It helps to discover some curious notes in the Franklin character, and serves to explain in a measure why with some conservative Philadelphians the memory of Benjamin Franklin is still that of a discredited adventurer. I do not, however, see that it is in the least necessary to dwell upon a similar misadventure of Benedict Arnold, because his treason overshadowed all minor misconduct, however evil that may have been.

In a recent life of Abraham Lincoln, it was disconcerting to find how much space was given to his humble origin and the ungainliness of his person, and how much emphasis was laid upon them. A true artist, even in literature, will do more with a few lines rightly drawn than will another who fills a sketch-book. There is much profitable instruction in that definition for making a statue given by a sculptor to an inquisitive tyro: “All you have to do is to chip off the marble that you don’t need.” It is just possible that enough has been said of the limitations of Abraham Lincoln, and that there may be a sort of national snobbishness in dwelling overmuch on defects for which he was not responsible. It is equivalent to saying: “See what an American can do, even when he has the heaviest sort of handicap.” Besides, we must not forget that Lincoln was a good name long before he bore it, that his stock came from Massachusetts, and that strong blood is very persistent. Truth-telling must not be confounded with an undue insistence upon relatively unimportant facts; the latter naturally slips into sentimentality.

A rather sleek person once called to see me at the Library, and informed me that he had been detailed by a committee of some sort to look up the character of George Washington—that many persons were disturbed at rumors floating about in regard to Washington’s private life, and that he had taken upon himself the task of investigating the matter. I think that he was sincere, and that he hoped to be able to make out a good bill of health for the Father of his Country; but the nature of the quest did not please me, and I was brief with him. Like the man in the Bible, he went away exceeding sorrowful. I found, at that time, one answer to the question which I have now raised, from something which the late Paul Leicester Ford told me on the publication of his True George Washington. He said that Washington’s reputation had suffered from the weight of its own grandeur; that people, in short, were getting tired of his virtues and excellencies through overpraise. Mr. Ford accordingly set about an estimate of him as a human, not superhuman, being. Or better, perhaps, he left the original grandeur of the statue, and set Washington on a new pedestal. That, I think, was a wiser way. He told the truth by revealing the limitations only as they contributed to the entire character.

Leaving this phase of the question, which is concerned only with what we shall deliberately accept or reject on grounds of prudence or good taste, we come to consider the more difficult phase of historical interpretation, — the unconscious effect of temperament or of preconceived theories and methods. Telling the truth as we think we see it may easily start us down a road more delusive than that travelled by the more timorous and the less veracious. Without attempting to solve the meaning of the word “history” — and it is difficult of precise definition — we may safely accept Michelet’s commonplace that “annals are not history;” but at the moment of acceptance, certain other elements are at once introduced into the general scheme of historical treatment, and among them is the tendency to treat the sequence of events as constituting a logical, consistent whole. This still further leads to the romantic, sentimental, and patriotic considerations which in some form or other do enter into the construction of historical work. Notwithstanding the endeavor to write history on the scientific or empirical basis, there is an insensible passing from the inductive to the deductive. Now I am not for a moment going to discuss the comparative merits of these two contradictory methods, or attempt to say how far they intermingle in most historical writing. The only point of value to me just now is to decide for myself whether the first of these methods, — the scientific or inductive way, — is not about as treacherous as the other, which is confessedly dangerous. I take it for granted that any historian worthy of the name, of either school, is by nature and training a discriminating, fair-minded, and conscientious man. One may be a partizan and still deserving of a high place, but a spirit of propagandism rules out any book. I saw a striking instance of this spirit lately in a book written for the edification rather than the instruction of a certain portion of our American youth. In speaking of the Waldenses, after devoting considerable space to a deliberate vilipending of them, the author closed his case by saying that at last it became “necessary to repress these sectaries!” That was the case of the Waldenses as presented to some American school children. It were safer to trust John Milton on this subject.

I have in mind such a work as Hildreth’s History of the United States, admittedly written by a partizan but singularly free, being what it is, from undue bias. A certain faith in his hypothesis may here have strengthened the historian’s hand and sweetened his historical disposition. An extreme opposite of this would be some of the writings of Mr. Charles Francis Adams and his brother, Mr. Brooks Adams — both men of extraordinary ability and information, traditional and acquired, and both possessed of a consuming desire to tell the truth. Discarding instantly all conventional interpretations of our remoter past, and feeling no need to follow that current of imaginative enthusiasm which guides most of us more than we are probably aware, these scholars, intensely modern and almost iconoclastic, bring to their aid many powerful facts tending to destroy our prepossession in favor of our earliest history. I certainly do not dispute these facts, and I cannot pretend to have the learning or authority to discredit such writers, yet I am not convinced that they have invalidated our concepts of the past, legendary as they may possibly be. Historical conceptions are not wholly due to an accurate assemblage of a portion — even a large portion — of the facts. The past as we at this moment conceive it is a sort of slowly formed growth, the purpose of which may be disfigured by many absurd accretions and deformities, yet the main body of which remains sound. It may be a fair question to ask whether, eliminating from our treatment the sympathetic chord which binds us to what has gone before, we can safely trust ourselves, in a detached, modern way, to deal with bygone facts as we should have to deal with them if they had happened only yesterday.

If literature is really a high expression of the truth of life itself, I am fairly prepared to believe that history, written with a just use of the dramatic element seemingly inherent therein, may, on the whole, be safer to trust than the bare presentation of carefully attested facts logically and unimaginatively presented. If we put faith in the great interpreters in other fields of thought, why may we not also trust the historian who has dramatic unity? The generality of mankind certainly has not the wit to decide on the merit of the evidence as offered by the annalistic writers.

The truth is one thing, and he who tells it is another. When I was a small boy I had the doubtful privilege of riding on a rail for a few moments, because my father felt that the policy of Andrew Johnson might be worthy of thoughtful consideration. As I recall this episode in my early life, I also recall that most of the young patriots who raised me, blameless as an Ethiopian, to this bad eminence, have lived to accept office under an administration of quite a different political stripe from that which they then so devotedly followed. Now I have often wondered in just what way they would choose to treat this early escapade on strictly historical lines. They would be obliged, I am sure, to generalize a little.

How far prudential reasons ought to enter into the acceptance or rejection of facts is a most difficult problem. Cost what it may, we certainly ought to lean heavily in favor of telling the truth, however relentless it may prove to be. It would be interesting to know how far the ancient historians were inspired with a desire to be inclusive as well as exact. Their chronicles have the appearance of being simple and direct, yet we must look with suspicion on the speeches, so wonderfully remembered, made by victorious generals and incorporated in the texts. If there were historiographers in those days, to them probably came the rewards of patronage. Better the days of hard favored critics than those of Mæcenas.

We are now reasonably free from ecclesiastical and even political prejudice in our historical estimates, but it may still be true that we are somewhat fettered by a desire to protect the integrity of our social traditions. In gathering materials for writing a study of William Lloyd Garrison from the standpoint of our national life in its formative period, I am impressed with the complete social cleavages of those days. Prejudices strong then are strong to-day. The situation in one sense remains much as it was. To tell the truth, as it appeared to the various contestants, is but to revive the old animosities; but just as grass grows as graciously on battlefields as elsewhere, so does the softening lapse of time enable us to temper the harsh and unpalatable truth with generous interpretations. Garrison now appears, clad in the habit of a Hebrew prophet, no longer the strident and unappeasable foe of those of more moderate opinions. If he looms large, so too does Calhoun, who saw, what Garrison did not see, the irreconcilability of totally opposite conditions of race.

The truths which we can afford to omit without becoming untruthful, are those which only irritate and antagonize, and which contribute to no useful end. The truths which we cannot afford to ignore are those which, after every reasonable elimination of irritating factors has been made, remain essential to the historical structure.

The more compact and highly developed the life of a community, the more difficult, I suppose, the complete unfolding of historical truth will become. Possibly we of this city are in some danger of overmuch caution. Treading on the toes of a man’s ancestors will easily make him wince; but we should not, if we are courageous, let this discourage us. It is possible to offend very gracefully; and it is also a comfort to have ancestors whose bones are of enough importance to be disturbed even by hostile hands.

The reading of this paper was followed by a long discussion in which President Kittredge, the Rev. Dr. Edward H. Hall, and Messrs. Andrew McFarland Davis, Adams S. Hill, Francis H. Lincoln, and William Watson participated.

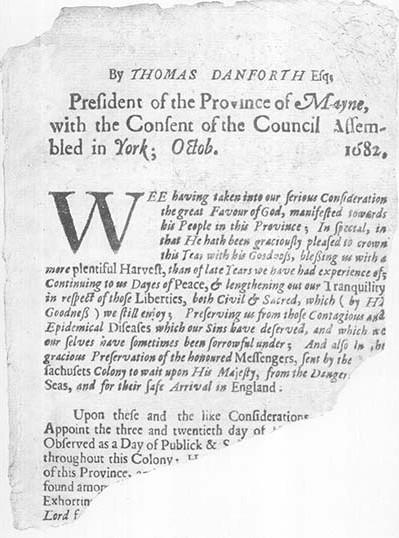

Mr. Henry H. Edes exhibited a photographic copy of a unique Thanksgiving Proclamation issued by Thomas Danforth, as President of the Province of Maine, in October, 1682, and spoke as follows:

At the Society’s meeting in January, 1898,153 I communicated an original manuscript Thanksgiving Proclamation issued in December, 1681, by John Davis of York, then Deputy-President of the Province of Maine. That state paper proved to be entirely unknown to the historical scholars in Maine, and no mention or record of it, or any reference, direct or incidental, to it, could be found in the York Court Records where it would naturally find a place.

Within a few weeks our associate, Mr. Charles K. Bolton, called my attention to an imperfect printed copy of another Maine Thanksgiving Proclamation which, upon investigation, also appears to be unique. No mention of this Proclamation or this event appeal’s in the York Court Records,154 nor is either known to historical scholars. Through the courtesy of its owner, Mr. Charles Butler Brooks of Boston, I was permitted to take a photographic copy, and I have brought with me this afternoon a print made from this negative.

The text of this paper follows.

Engraved for The Colonial Society of Massachusetts from the original in the possession of Charles Butler Brooks, Esquire

The Massachusetts Colony Records, under date of the fifteenth of February, 1681–82, state that —

At the opening of this Court, his majestjes letter to the Goũnor & Company, brought by Mr Edward Randolph, bearing date 21th of October, 1681, was read in open Court, the whole Court mett together.155

Then follows a “most humble address “to the King in which it is stated that the Governor and Company have —

dispatched our worthy ffreinds Joseph Dudley & John Richards, our messengers, humbly to give your majtie account of what wee haue donne for the regulation of our lawes, etc.156

On the twentieth of March —

The whole Court mett & voted together, by papers, for agents to goe & wayte on his majty, &c, & on the scrutiny, Wm Stoughton, Esq., was chosen for one wth 21 voates, & Joseph Dudley, Esq, was chosen for the other by 18.157

On the twenty-third of March —

Mr. Stoughton hauing manifested his greate dissatisfaction from accepting and vndertaking the employment & suruice he hath binn chosen to by this Court, &c, after the Court eurnestly once & againe desiring his acceptane, but he persisting in his answer already given, the whole Court came together, & by their voate Jno Richards, Esq, was chosen to be the other agent.158

Then follow the Instructions to the Agents, or Messengers. In this connection, Palfrey says:

Danforth, who had come from Maine, as was bis custom, to take his place in the General Court, was now chairman of the Committee for preparing instructions for the agents.159 He took care that Dudley (whom no man knew better), and his easy colleague, should be carefully limited as to the exercise of a discretion so liable to abuse.160

On the thirtieth of March, 1683, another Address to the King, further Instructions to Dudley and Richards, and their Commission, are recorded in the Colony Records,161 in which the Agents are impowered “joyntly, and not seuerally, to attend vpon his majesty “and to represent the Colony in the weighty matters committed to their care. While the record is silent as to the personnel of the Committee which draughted these Instructions, there can be little doubt that Danforth, who was in attendance upon this Special Session of the Court, had a principal hand in their preparation.

The Agents left Boston about the first of June, 1682, and “after a tedious passage of nearly twelve weeks,” arrived in England where “they lost no time in approaching the Privy Council.”162

Randolph, fitly characterized as “the Evil Genius of New England,” who had been chiefly instrumental in bringing these troubles upon the Colony, was an interested observer here in Boston of the proceedings of the General Court, and industrious with his pen in keeping the English Government informed of the progress of events, not forgetting to impress upon his correspondents his own jaundiced view of what was done and of the men who had been sent to represent the Colony at London. That his statements concerning the Agents and their constituents were scandalously false was recognized in print by such a stanch representative of the Royal prerogative as Hutchinson,163 in 1769, and they are disproved by Randolph’s own letters of an earlier date written in a saner mood.164

In a letter to the Bishop of London, dated at Boston, 29 May, 1682, Randolph draws the character of Dudley with a frankness more refreshing than complimentary:

Necessity, and not duty, hath obliged this government to send over two agents to England; they are like to the two consuls of Rome, Cesar and Bibulus. Major Dudley is a great opposer of the faction heere, against which I have now articled to his Majesty, who, if he finds things resolutely manniged, will cringe and bow to any thing; he hath his fortune to make in the world, and if his Majesty, upon alteration of the government, make him captain of the castle of Boston and the forts in the colloney, his Majesty will gaine a popular man and obleidge the better party.

. . . Your Lordship hath a great pledge for such ministers as your Lordship shall thinke convenient to send over, for their civell treatment, and I thinke no person fitter than Major Dudley, their agent, to accompany them, who will be very carefull to have them settled as ordered in England. He is one of the commissioners for the money sent over for the converting the Indians; I give him two or three lines to recommend him to your Lordships favour, soe far as he may bee serviceable to the designe; as for Capt. Richards, he is one of the faction, a man of meane extraction, coming over a poore servant, as most of the faction were at their first planting heere, but by extraordioary feats and coussinadge have gott them great estates in land, especially Danford, so that if his Majesty doe fine them sufficiently, and well if they escape soe, they can goe to worke for more. As for Mr. Richards, he ought to be kept very safe till all things tending to the quiett and regulation of this government be perfectly settled.165

From a letter to the Earl of Clarendon, I make the following extract, which reveals Randolph’s enmity to others besides Richards, especially Danforth, and his own annoyance at finding that his malignity toward the Colony had become fully known to the authorities here:

Boston, June 14th, 1682.

Right honourable,

I Wrote your Lordship largely by Mr. Foy,166 which I hope is come to your Lordships hands. Our agents are sayled from hence about a fortnight ago. Wee heare, Maj. Dudley, one of them, is very sick of a feavor and not like to hold out the voyage, Mr. Richards, the other, one of Danforths faction and a great opposer of the governor, will, upon Maj. Dudleys death, have an opportunity to say what he pleaseth, in defence of the severall misdemeanors objected against them and their faction.

They have been these 2 yeares raysing money upon the poore inhabitants, to make friends at court, certainly they have some there, too nigh the councill chamber, otherwise they could not have coppies of my petition against their government, my articles of high misdetneanures against Danforth, and now of Mr. Cranfields instructions and negotiations in the province of New-Hampshire.

. . . I was very much threatned for my protest against their navall office, but it was at a time when they heard of troubles in England; but, since, I am very easy, and they would be glad to heare no more of it. His Majestie commanded them to repay me the money they tooke from me by their arbitrary orders, which the faction would not heare of, I have therefore arrested Mr. Danforth167 for 10l. part of that money, and their treasurer, Mr. Russell, for 5l. due to me for a fine, and I am to have a tryall with them. I humbly beseech your Lordship that I may have coesideration for all my losses and money laid out in prosecuting seizures here, in the year 1680. If I may not have it out of his Majesties treasury in England, that the heads of this faction here may be strictly prosecuted and fined for their treasons and misdemeanures, and my money paid out of their fines.168

To a letter to Sir Lionel Jenkins, written by Randolph at this time, is this postscript:

Nothing these agents promise may be depended upon, if they are suffered both to depart till his Majesty have a full account that all here is regulated as promised.169

Fortunately we are not without some written testimony concerning these events under the hand of Richards himself during his stay in London, since a few of his letters to Increase Mather have been preserved in print.170

On the eleventh of October, 1682, the Massachusetts Colony Records state that —

The Court order a day of thanksgiving to be kept throughout ye jurisdiction ye 23 November next, for the blessings of the yeare, peace, &c, our agents or messengers preservation, &c; Wch was sent to ye press & printed, & kept accordingly.

It is ordered, that the Treasurer make payment vnto Mr Joseph Dudley & Mr John Richards, or to their order, fiffty pounds a peece money, and is in part sattisfaction for their present service for ye publick.171

This Proclamation is noted by Dr. Love,172 but he makes no mention of Danforth’s Proclamation in the Province of Maine, which was doubtless issued immediately after the adjournment of the General Court at Boston.

In his History of the State of Maine, Governor Williamson sums up the situation which culminated in the Quo Warranto proceedings against the Charter in a paragraph with which this paper may be fitly closed:

It was auspicious to the Province at this time [1683], that she was separated from Massachusetts, harrassed as that colony was by her persevering enemies. Even twenty of her ablest and most popular statesmen, President Danforth being one, were not only denounced by Randolph for their republican patriotism and politics, as basely factious: but they had moreover been pursued by him, two years, in articles of impeachment or accusation before the throne; charging them with high misdemeanors and offences. With them was also identified the charter of Massachusetts, which was assailed with so much force and virulence, that the General Court directed their agents in England, to resign the title-deeds of Maine to the crown, provided any such expedient could preserve from wreck the colony charter — yet never to concede a single right or principle it contained.

But as unconditional submission was what the king imperiously requiredl the duties of the agents were at an end; and Oct. 23, they arrived in Boston, closely followed by Randolph, with a writ of Quo Warranto sued out of the Chancery Court at Whitehall, July 20th, preceding.173

Mr. Elias Harlow Russell of Worcester was elected a Resident Member.

Comt.

Comt.

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly

Committee

Committee