TRANSACTIONS OF THE COLONIAL SOCIETY OF MASSACHUSETTS.

DECEMBER MEETING, 1904.

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held at No. 25 Beacon Street, Boston, on Thursday, 22 December, 1904, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the President, George Lyman Kittredge, LL.D., in the chair.

The Records of the Annual Meeting were read and approved. The President announced that, in pursuance of the changes in the By-Laws made at the Annual Meeting, the Council had elected Mr. Albert Matthews Editor of Publications for the ensuing year.

Mr. Lindsay Swift made the following communication:

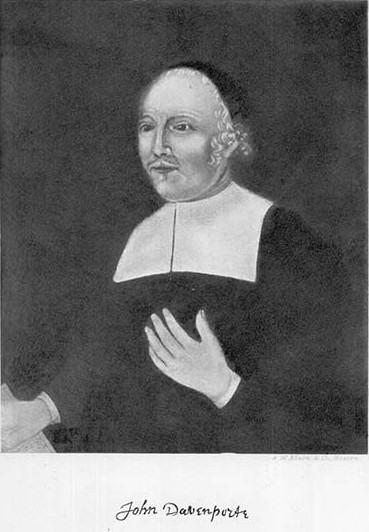

JOHN DAVENPORT’S ELECTION SERMON OF 1669.

The recent purchase by the Boston Public Library of a hitherto unknown Massachusetts Election Sermon gives me an opportunity to say a few words on a subject which I sought to treat with some thoroughness several years ago.1 There were thirty occasions on which the Election Sermon is known to have been preached, but not known to have been printed; nineteen of these occasions were before the year 1675, and among them I was obliged to include that for the year 1669, when John Davenport preached. Cotton Mather, in his life of Davenport,— Chrysostomus Nov-Anglorum, as he calls him, — says: “Nor would I forget a Sermon of his on 2 Sam. 23.3. at the Anniversary Court of Election at Boston 1669. afterwards Published.”2 I had then no evidence that Mather had ever seen this sermon, but I am now sure, by comparing his words with Davenport’s text, that he used it freely, and even copied in effect certain passages from it.

But with the exception of Mather we cannot say with assurance that any person devoted to New England history has ever seen or used a copy, since the work appeared in 1670. This bibliographical and historic treasure was for the first time to our knowledge brought to public attention in the Catalogue of the Library of Robert Proud, the historian of Pennsylvania, which was sold at the auction rooms of Davis and Harvey in Philadelphia, on 8 May, 1903, and the days following, under the direction of S. V. Henkels. The sermon was numbered 587 in the catalogue. It was sold to Dodd, Mead and Company for $180; and in February, 1904, this firm sold it to the Public Library for $250.

The Proud Catalogue describes it as a “Beautiful copy of an exceedingly rare Boston imprint, replete with early New England history.” This is true so far as it goes, but the maker of the catalogue, and possibly the owner of the sermon, had probably no knowledge of its exceeding preciousness. Since the existence of Davenport’s sermon has been only a legend for over two hundred years, with no facts to support it; and since those industrious collectors, Thomas Prince and Samuel Sewall, failed to secure copies, it is not unreasonable to assume that this copy is unique. But why? Although these early Election Sermons are all rare and hard to buy, copies of them do turn up occasionally. John Davenport’s other works are not choice in the way that the Bay Psalm Book or the Indian Bible is choice. I can offer no suggestion, unless it be that the deceased minister’s executors, realizing that the estate was encumbered by the unsold and unsalable remnant of an edition, quietly “used their judgment” and destroyed it. The sermon was preached on 19 May, 1669, and on March fifteenth following Davenport died, possibly too feeble before his death to have had much to do with the preparation of the work for the press. The date of imprint indicates that he could have had no hand in the personal distribution of copies. Mr. Franklin B. Dexter wrote in 1875, “not a copy is now discoverable.” The Boston Public Library gives Cambridge as the place of imprint, but Mr. Julius H. Tuttle, Assistant Librarian of the Massachusetts Historical Society, good authority in such matters, thinks that this sermon was printed in London, although he is confronted with the fact that there is no entry of the title in Arber’s Term Catalogues. Certainly it is not so good a piece of work as Davenport’s Gods Call to His People, printed the year before at Cambridge by Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson for John Usher in Boston, and entered, by the way, in Arber’s Term Catalogues (I. 35) as also printed in London in May, 1670. If Mr. Tuttle’s judgment is not in error, and the date of imprint means New Style, the Election Sermon could not have arrived from London until after the death of Davenport. It is possible that the references, to be mentioned later, in the sermon to the dissatisfactions in the First Church which led to the formation of the Third (Old South) Church caused those who had the power to do so to suppress the edition, with the exception perhaps of a few copies. But this is all mere conjecture, however certain it is that these inter-ecclesiastical difficulties hastened John Davenport’s death.

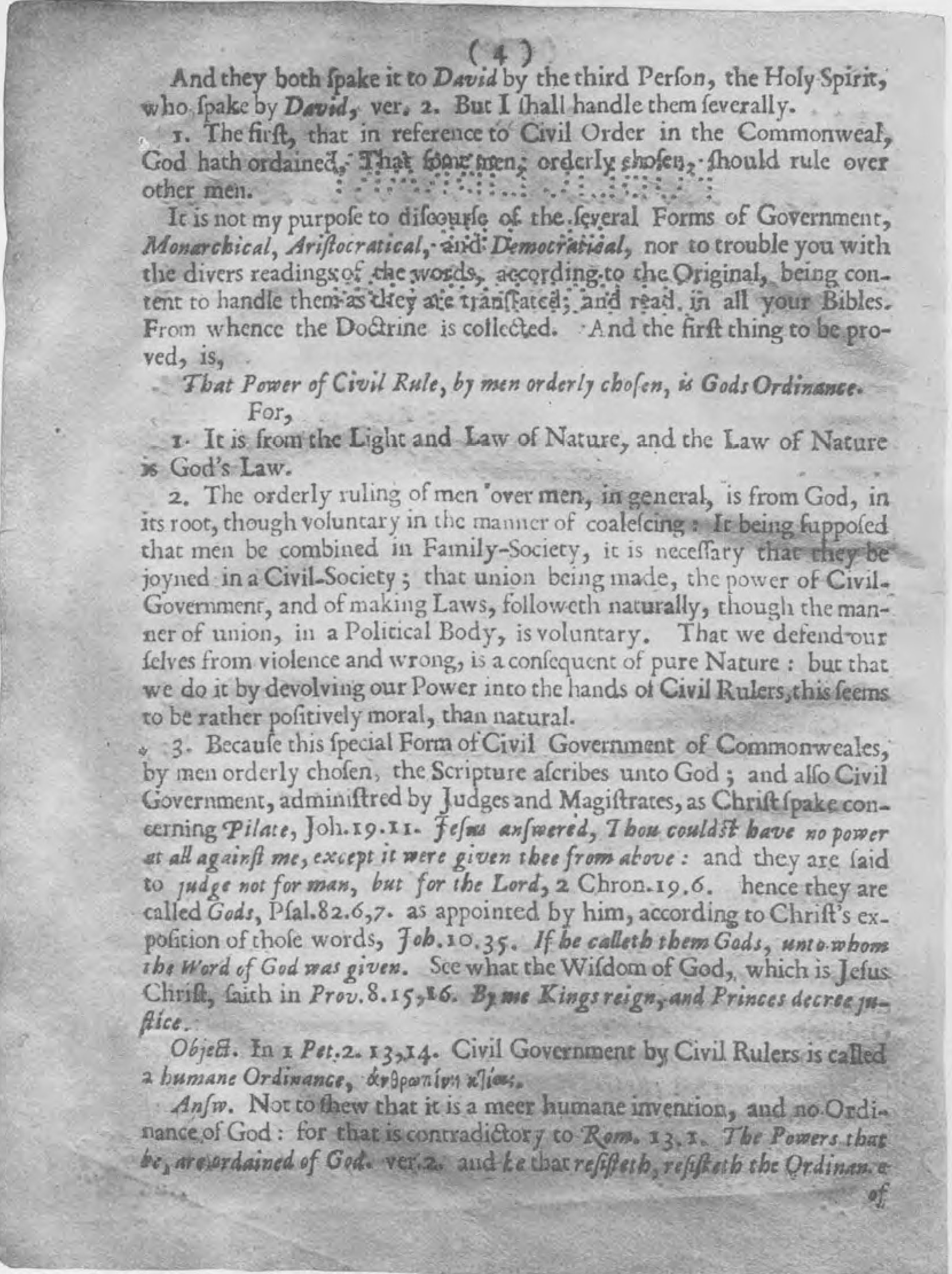

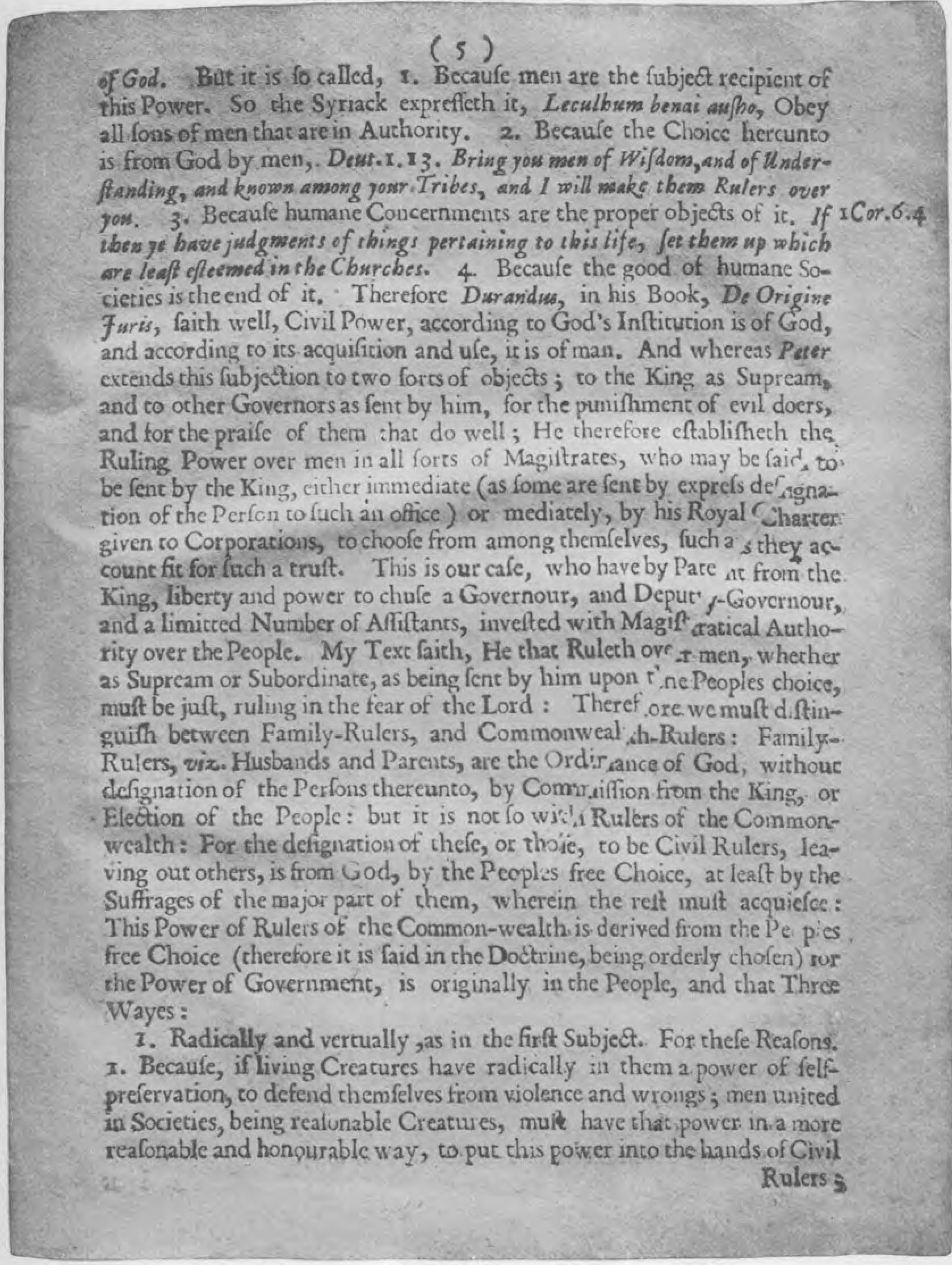

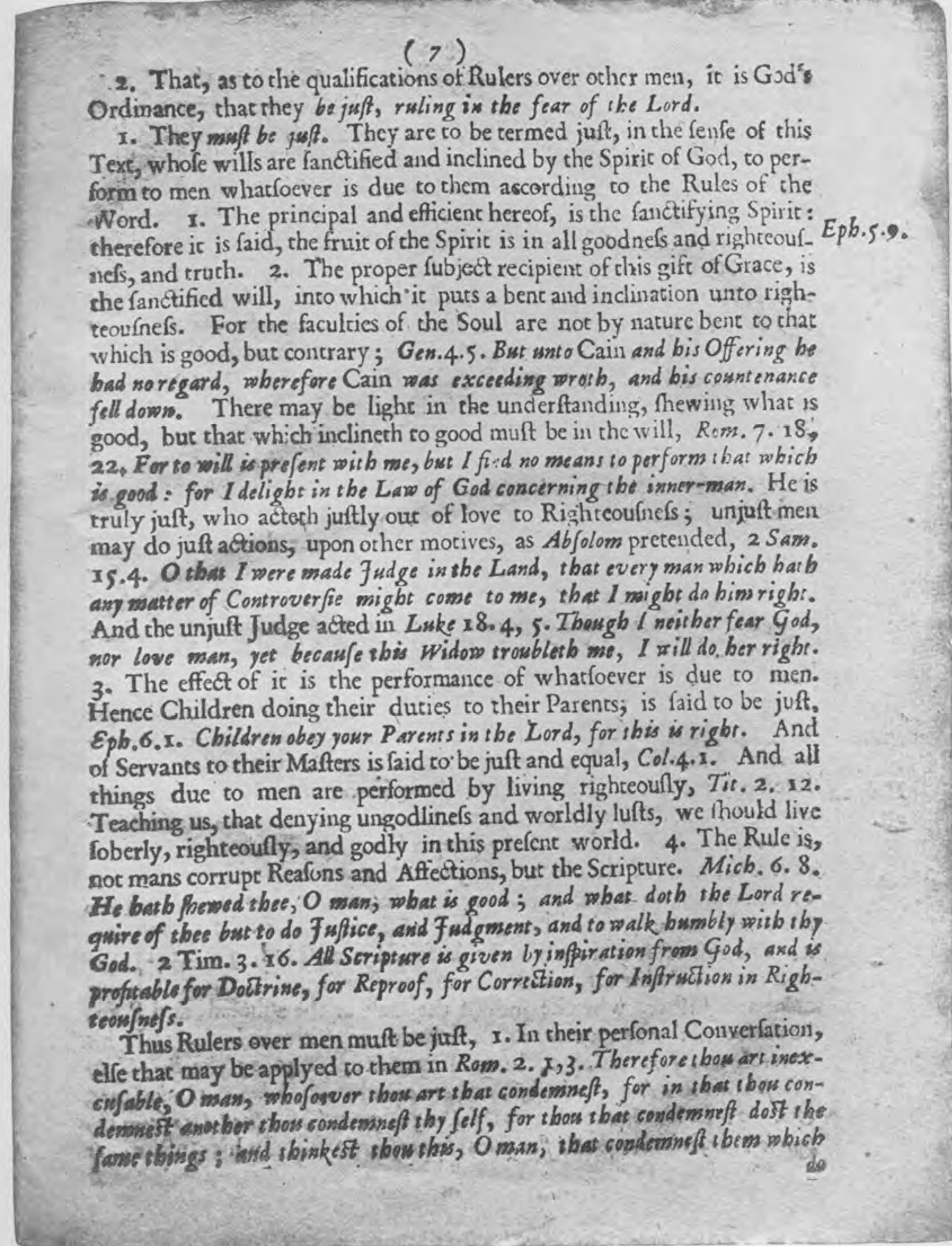

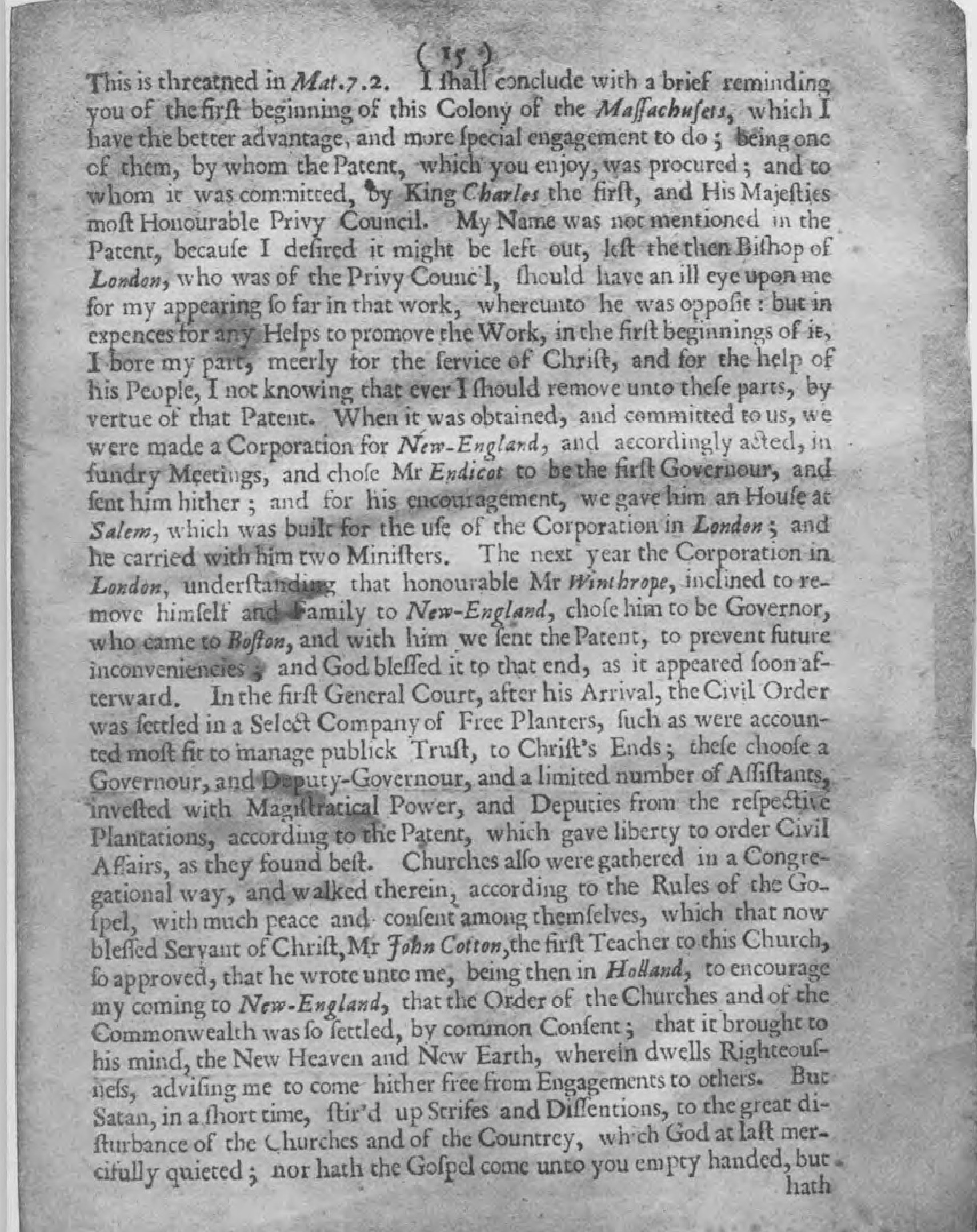

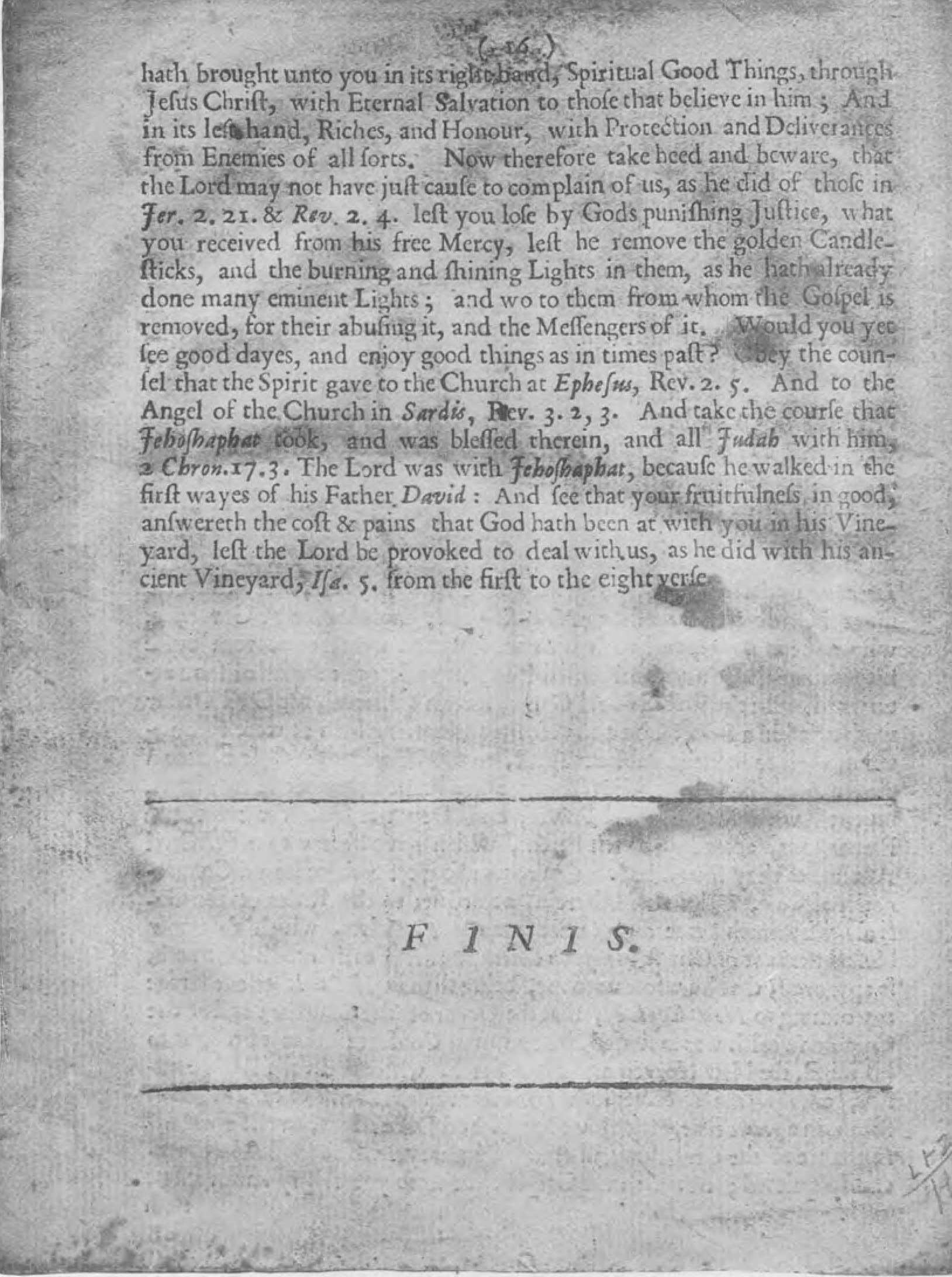

The book itself and its contents deserve some attention. It is a small quarto, with trimmed edges, and measures seven and a quarter inches in height by five and a half inches in width. The title-page is sightly, with its large and well-balanced type superior to that within. The text is from 2 Samuel, XXIII. 3: “The God of Israel said, the Rock of Israel spake to me, He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.” It is of the conventional pattern —this sermon — with mingled learning and exhortation on the duties of the true ruler. With a scholar’s familiarity, the preacher quotes from Durandus, Nazianzen, and the Syriac, but mostly from Holy Writ.

A few years before, in 1662, Davenport had been among the minority in the Synod which sat in Boston to ponder the grave matter of consenting to the admission of baptized children to the privileges of the church, and in particular to the offering, by them, as adults, their own offspring for baptism, though without profession of faith on their own part. John Davenport was opposed to the Half-Way Covenant and all such innovations, and, polemic as he was by nature, could not refrain seven years later from making a few indirect references to the dangers of synods and councils.

Avoid carefully imposing upon anything that Christ hath not put upon them, viz. I. Men’s opinions, especially when they are such as prevailed in an hour of temptation, though consented to by the major part of a Topical Synod yet disliked by some of themselves, and by other godly ministers.

Davenport also referred, in all likelihood, to the troubles in the First Church in Boston, which finally led to the leaving of twenty-eight members who “after much tribulation, and by the aid of the first well-marked Ex-parte Council ever held in New England”3 became the Third or Old South Church. A full account of the peculiar circumstances under which Davenport came from New Haven to Boston — circumstances which largely contributed to the separation of some of the members — is in the History of the Old South Church by Hamilton A. Hill, who mistakenly gives the text of our election sermon as from 1 Samuel, XXIII. 5. This reason is also accepted by Thomas Pemberton.4 It was Mr. Hill’s opinion that Davenport referred in the sermon to the immediate controversy and to the schismatic opponents of his installation. It seems that the Deputies, who favored the side of the Old Church, “passed the customary vote of thanks” for the sermon, but that the Assistants refused to concur because Davenport had shown himself a partizan on the occasion of its delivery.

A remonstrance was therefore sent down to the deputies, declaring the vote of thanks “to be altogether unseasonable, many passages in the said sermon being ill-resented by the Reverend Elders of other churches and many serious persons,” and the request was made that “they would forbeare further proceeding therein.” Governor Bellingham, who was in the chair, refused to put the question on sending down this remonstrance, and at the call of his associates it was put by Simon Bradstreet, who himself, a few years later, became a member of the Third Church. The deputies, however, refused to give way.5

Surely there were reasons of prudence for exercising discretion in regard to perpetuating this quarrel beyond Davenport’s death.

But more interesting than any bygone theological or ecclesiastical differences is a passage toward the end of the sermon wherein Davenport lays claim, and truthfully, to an important share in the foundation of the Colony. It is valuable enough to quote, and especially since no historian’s eye, except that of Cotton Mather, has probably ever fallen upon it. Davenport says:

I shall conclude with a brief reminding you of the first beginning of this Colony of the Massachusets, which I have the better advantage, and more special engagement to do; being one of them, by whom the Patent, which you enjoy, was procured; and to whom it was committed, by King Charles the first, and His Majesties most Honourable Privy Council. My Name was not mentioned in the Patent, because I desired it might be left out, lest the then Bishop of London [Laud], who was of the Privy Council, should have an ill eye upon me for my appearing so far in that work, wherunto he was opposit: but in expences for any Helps to promove the Work, in the first beginnings of it, I bore my part, meerly for the service of Christ, and for the help of his People, I not knowing that ever I should remove unto these parts, by vertue of that Patent. When it was obtained, and committed to us, we were made a Corporation for New-England, and accordingly acted, in sundry Meetings, and chose Mr Endicot to be the first Governour, and sent him hither; and for his encouragement, we gave him an House at Salem, which was built for the use of the Corporation in London; and he carried with him two Ministers. The next year the Corporation in London, understanding that honourable Mr Winthrope, inclined to remove himself and Family to New-England, chose him to be Governor, who came to Boston, and with him we sent the Patent, to prevent future inconveniencies.

After a few lines on the starting of the churches “in a Congregational way,” he closes by an exhortation not to forsake the old paths, lest “the golden Candlesticks” and “the burning and shining Lights” be removed.

Twenty-five years before this, was published in London (1645) John Cotton’s The Covenant of Gods free Grace, Most sweetly unfolded, and comfortably applied to a disquieted Soul. It was preached from verse 5 of the same book and chapter of Samuel from which Davenport preached his Election Sermon, and at the end was added John Davenport’s Profession of Faith made “at his admission into one of the Churches there.” The church was of course the First Church of Quinnipiac or New Haven, definitely organized in August, 1639. The first edition of the Profession was printed in 1642. Davenport continued as Pastor of this church until he went to Boston in May, 1668, and was ordained in December. The Teacher of the church, William Hooke, was his colleague from 1644 to 1656, and then became one of the domestic chaplains at Whitehall to Cromwell, who was a kinsman of Hooke’s wife.

It is germane to our immediate subject to recall that in February, 1666, in a letter to the younger Winthrop, Davenport declined to preach the Election Sermon at Hartford, in March, for “sundry other (besides his unfitness for the journey from New Haven) weighty reasons, whereby I am strongly and necessarily hindred from that service, which may more conveniently be given by word of mouth to your Honoured Selfe, then expressed by wrighting.” In a postscript he adds: “The reason, which it pleased you to give, why I was not formerly desired to preach at the Election, holdeth as strong against my being invited thereunto now. . . . Therefore, I pray, desist from that motion to mee, and urge it upon some fitter minister and dwelling nearer to the place of the Election-Courte.”6 One reason for his thus declining to preach, we may be sure, was the disturbed relations then existing between New Haven and Hartford.

It would be an agreeable task to dwell for a moment on the character of John Davenport. He was a righteous man after his own day and generation, yet he wrote that strange letter to Temple in regard to the regicides which Mr. Dexter sadly wishes “for his sake were blotted out.”7 “His Custom was,” according to Mather, “to sit up very late at his Lucubrations,” and his writings clearly show this to be true. Exacting too, the same eulogist finds him to have been, admitting that “over-much, were the Golden Snuffers of the Sanctuary employ’d by him in his Exercise of Discipline.”8 But he has been ably considered by such men as Leonard Bacon and Mr. Dexter, and I have no excuse for going beyond my intention to make an announcement to the Society of the discovery of this supposedly lost book, which earlier students would have been eager to consult.

The Rev. John Davenport’s Massachusetts Election Sermon of 1669 follows, reproduced in facsimile.

Engraved for The Colonial Society of Massachusetts from the original in the possession of Yale University

Engraved for The Colonial Society of Massachusetts from an original in the possession of the Boston Public Library

In some lively and entertaining remarks made before the Massachusetts Historical Society in 1883, Mr. Charles Francis Adams began a discussion as to the proper editing of old manuscripts and books.9 Mr. Adams thinks that modern editors err in retaining the exact spelling, abbreviations, capitalization, and punctuation of the original manuscripts or the original printed editions. Mr. Adams spoke feelingly because he had recently edited for the Prince Society Thomas Morton’s New English Canaan. In his introduction to that work, Mr. Adams returned to the subject, and said:

There is some reason to think that the fancy for exact reproduction in typography has of late years been carried to an extreme. Not only have peculiarities of spelling, capitalization and type, which were really characteristic of the past, been carefully followed, but abbreviations and figures have been reproduced in type, which formerly were confined to manuscripts, and are certainly never found in the better printed books of the same period. It is certainly desirable in reprinting quaint works, which it is not supposed will ever pass into the hands of general readers, to have them appear in the dress of the time to which they belong. Indeed they cannot be modernized in spelling, use of capitals, or even, altogether, in punctuation, without losing something of their flavor. Yet, this notwithstanding, there is no good reason why gross and manifest blunders, due to the ignorance of compositors and the carelessness of proof-readers, should be jealously perpetuated as if they were sacred things. This assuredly is carrying the spirit of faithful reproduction to fanaticism. It is Chinese.

The rule followed, therefore, in the present edition has been to reproduce the New Canaan as it appeared in the Amsterdam edition of 1637, correcting only the punctuation, and such errors of the press as are manifest and unmistakable. Very few changes have been made in the use of capitals, and those only where it is obvious that a letter of one kind in the copy was mistaken by the compositor for a letter of another kind. . . . The spelling has in no case been changed except where the error, as in the case already cited of “muit” for “mint,” is manifestly due to printers’ blunders. . . . No conjectural readings whatsoever have been inserted in the text.10

In the discussion above referred to, Mr. Adams’s views met with assent, unqualified or modified, from Dr. William Everett and Charles Deane, but were totally rejected by Francis Parkman, Dr. Samuel A. Green, and the Rev. Dr. Henry M. Dexter. It will perhaps be thought that the criticism of such scholars as Parkman, Dexter, and Dr. Green does not need reinforcement; yet they spoke as historians, while something fresh may be said from a different standpoint. To the historian, the exact spelling of a word may be a matter of indifference, but to the student of language it is of supreme importance. American writings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have thus far been examined chiefly by the historians; yet they are not without interest from other points of view, and to the literary investigator they are, as Dr. Murray wrote me five or six years ago, “a veritable mine of wealth.”

With much that Mr. Adams says as to the Chinese fanaticism of faithful reproduction, I confess that I am in sympathy; yet there are certain aspects of the case as put by Mr. Adams against which it is impossible not to protest. There would seem to be no good reason for perpetuating the long “s,” absolutely without significance in itself and so easily mistaken for “f;” and I cannot help thinking that the casting of special characters, as was done long ago in the Massachusetts and Plymouth Colony Records, and more recently in the Records of the Court of Assistants, — thus making it necessary for the reader to refer constantly to a key, — is going to an extreme. On the other hand, when Mr. Adams advocates the alteration of the original text merely because, in the opinion of the editor, the original readings are misprints, the question at once arises, How does the editor know that they are misprints? Much might be said on this topic, for I frequently run across unwarrantable editorial changes, but I will confine myself to three illustrations.

As a topographical term, the word interval is now found in two forms only, — “interval” and “intervale.” But in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the word was spelled in no fewer than fourteen different ways. In his General History of New England, written for publication about 1680, the Rev. William Hubbard spoke of “rich and fruitfull spots of land, such as they,” that is, the people, “call intervail land,” and the word so appears in the first edition of this work, published in 1815. When the work was reprinted in 1848, “intervail” was altered to “interval,” and so a form interesting in itself, which is found in a passage containing the earliest comment on the term, and which throws light on the etymology of “intervale,” is altered.11

My second illustration is of a word which, through editorial supervision, is made, like some conjuror’s trick, to disappear altogether. In 1716 Thomas Church wrote, at the dictation of his father Benjamin Church, the noted Indian fighter, Entertaining Passages Relating to Philip’s War. At page 66, Church remarked:

In the Year 1690. was the Expedition to Canada, . . . And the said Church going down to Charlestown to take his leave of some of his Relations, and Friends, who were going in that Expedition, promised his Wife and Family not to go into Boston, the Small Pox being very brief there.

When Church’s book was reprinted by Ezra Stiles at Newport in 1772, “brief” was silently altered to “rife” (p. 107). The learned President of Yale doubtless thought that “brief” was a printer’s error. Between 1827 and 1867 many impressions of Church’s book appeared, in every one of which that has come under my eye the word “rife” occurs.12 This is explained by the fact that the editor, Samuel G. Drake, had never seen the original edition and so used as copy the Stiles edition of 1772. In 1867 the Rev. Henry M. Dexter brought out an annotated edition of Church’s book. Dr. Dexter printed “brief” in the text, but added this note: “An evident misprint for ‘rife,’ which Dr. Stiles corrected” (II. 37). Let us examine this statement.

At a meeting of the Governor and Council of Connecticut held at New London, 6 December, 1714, —

Jeremy Wilson . . . with his man . . . were sent to a farmhouse upon suspicion they might be infected with the small pox, coming from New Yorke where it is very brief.13

At a meeting of the Selectmen of Boston held 2 September, 1741, we read:

Whereas Information is given to the Select Men that the Yellow Fever is very brief in Philadelphia, therefore Voted, That Advice be asked of the Physicians of the Town.14

And on the ninth of September, “the Advice of Several of the Physicians” having been asked “respecting the yellow Fever being very brief in Philadelphia,” the Selectmen took measures accordingly.

Under date of 30 July, 1758, Samuel Thompson, then near Ticonderoga, wrote in his Diary:

Sunday, before day they did muster, and sent out seventy five men out of our Regiment, eleven out of our Company, who went a little after sunrise down the Lake, and what the News was, we could not tell; yet all sorts of camp news was brief about.15

It is noteworthy that Dr. Murray gives no quotation in the Oxford Dictionary for “brief” in this sense except from dictionaries,16 though in the English Dialect Dictionary Professor Wright cites a single example (dated 1809) previous to recent years. Hence it is seen that “brief,” so far from being, as Stiles and Dexter thought, “au evident misprint for ‘rife,’” has been employed both in England and in this country for two centuries, and the appearance of an obscure dialect word in America as early as 1714 is interesting.

My third illustration is taken from the Prince Society edition of Morton’s New English Canaan. In that work, first printed in 1637, Morton, referring to events that occurred in 1630, wrote:

Now (whiles this was in agitation, & was well urged by some of those partys, to have bin the upshot) unexpected (in the depth of winter, when all shippes were gone out of the land.) In comes Mṛ Wethercocke a proper Mariner; and they said; he could observe the winde: blow it high, blow it low, hee was resolved to lye at hull rather than incounter such a storme as mine Host had met with: and this was a man for their turne.17

Mr. Adams, under the impression that “hull” is a printer’s error, has altered it to “Hull,” and concludes that Morton was referring to our Massachusetts town of Hull. Our earliest certain allusion to the town of Hull by that name is under date of 29 May, 1644, when its name was changed by the General Court from Nantasket to Hull. Hence, if Mr. Adams’s alteration is justifiable, it shows that our town was colloquially known as Hull fourteen years before that name was officially adopted. It is of course possible that Mr. Adams is correct and that Morton did have in mind our Massachusetts town of Hull; but the change from “hull” to “Hull” is quite unnecessary, as the reading of the original text makes perfect sense. From the middle of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth centuries, the expressions “to hull” or “to lie at hull,” meaning to furl sails and to drift in a storm (or even in a calm), were in common use not only among seamen, but also, both in a literal and in a figurative sense, in the general literature of that period. This use is well exemplified in the two passages which follow. In 1617 Fynes Moryson, the English traveller, wrote:

The ninth day towards night, . . . not daring to enter the Riuer Elve before the next morning, wee strucke all sayles, and suffered our ship to bee tossed too and fro by the waues all that night, (which Marriners call lying at Hull).18

Writing in 1630, but referring to the memorable voyage of the Mayflower, Governor Bradford remarked:

In sundrie of these stormes the winds were so feirce, and ye seas so high, as they could not beare a knote of saile, but were forced to Hull, for diuerce days togither; And in one of them, as they thus lay at Hull in a mighty storme, a lustie yonge man (called John Howland) coming upon some occasion before ye graftings, was with a seele of ye shipe throwne into [the] sea.19

These three instances have been chosen because they illustrate the danger of interference with the original text. In the first instance, editorial “correction” has deprived us of a form of distinct etymological value; in the second, it has caused a dialect word to disappear altogether and in its place has substituted a quite different word; while in the third, it has changed a well-known sea term into an allusion to a town.

These instances show, I think, that there is but one safe rule to be pursued in editing old manuscripts and books, — namely, to print or reprint the original text so far as that can be done, relegating conjectures as to possible or probable errors to the footnotes. This was Dr. Dexter’s method, and though he himself erred in his comment on “brief,” yet we are all human, and he at least restored the word to the place from which it had been ousted by Stiles and by Drake.

The reading of this paper was followed by a discussion in which President Kittredge, Mr. Andrew McFarland Davis, and Mr. Lindsay Swift participated.

Mr. John Noble made the following communication:

SOME DOCUMENTARY FRAGMENTS TOUCHING THE WITCHCRAFT EPISODE OF 1692.

Fragments of old records sometimes prove valuable and suggestive, in themselves almost unwritten volumes to be read between the lines; sometimes, and perhaps oftener, dry and meagre, the husks of bygone harvests. The papers brought in to-day may seem of the latter class. They have, however, one possible merit, — they come to light after being buried for years, forgotten and probably unknown, with a multitude of alien companions, victims of the same fate. They may perhaps have another, in that whatever savors of witchcraft, by itself or by reminiscence, has somehow a bit of human interest about it. That vague, mysterious phenomenon appeals alike to the believer, the skeptic, the inquirer, and the every-day man; and the interest is of all sorts and shades.

The Salem epidemic of witchcraft has peculiar claims of its own, and any thing connected with it has certain attractions. It was a mere episode, a bubble in the current of Massachusetts history. It was local, short-lived and of slight proportions, and in some aspects has had an undue prominence. It was an occurrence by no means unnatural. It was perhaps rather to be expected. The Colony, though cut off by the estranging ocean, was still a part of the world, sharing its beliefs and its delusions. Conditions here were peculiarly favorable for such an outbreak. Two generations had gone by since the fathers landed. The stress and strain of the early days, engrossing all thoughts and activities, had passed. New ideas and interests had sprung up. New types of men had come into prominence. There was more time for brooding and pondering and noting providences and marvels. Speculation and superstition had new and clearer fields. The times were troublous, there was doubt, distrust, apprehensive foreboding. The situation, — a strip of territory between the sea and the forest with its gloom and mystery, its dangers and terrors both real and imaginary, peopled as it was with a race believed to be the children of Satan and his worshippers, — in itself invited it. Their Bible, as they read it, their code of law, divine and civil, sanctioned or even inculcated a belief in witchcraft and imposed responsibilities and duties, which their clergy were not slow in assuming.

A craze once started spreads like wildfire; — here the stubble though dry was scant, the fire was brisk but narrow and soon burnt itself out. The old papers submitted to-day are few and short. One set has to do with a case briefly referred to in Upham’s history of the Salem Witchcraft, that of Elizabeth Colson.

On the fourteenth of May, 1692, warrants were issued against Daniel Andrew; George Jacobs, Jr., and his wife Rebecca; Sarah Buckley, wife of Wilham, and his daughter Mary Whittredge; all of Salem Village; Elizabeth Hart, wife of Isaac of Lynn, and Thomas Farrar, Senior; Elizabeth Colson of Reading and Bethiah Carter of Woburn. Among the records in Essex, Upham finds few papers on file and little of interest relating to the last three cases.20 Of these nine persons, two were not found by the Constables, and escaped and found refuge abroad; three were brought in forthwith; and four, of whom one was Elizabeth Colson, were brought in shortly afterwards. The consequences of such bringing in were severe. As to the hardships endured in prison by persons so apprehended, some of the bills of expenses that have been preserved are somewhat suggestive; among them are bills for four pairs of fetters; mending and putting on one pair; making four pair of iron fetters and two pair of handcuffs, and putting them on the legs and hands of sundry persons, all women; eighteen pounds of iron for fetters; chains for two women; shackles for ten prisoners; one pair of irons for another woman; and most of the prisoners so fitted out were confined in jail for nearly a year.

There are two papers touching this case. One is the Deposition of the assistant of the officer sent to arrest her, giving some interesting experiences in the fruitless attempt. There is a slight difference as to date from that given by Upham as the beginning of proceedings. Perhaps this suspect was peculiarly elusive, and this may have been one of a series of attempts, and the interval longer than Upham gives. Whatever interest the old paper has is subjective rather than objective. The story is prosaic and unexciting; the occurrences commonplace; — a race with the natural outcome, — the inevitable cat, — the dog very like the dog of to-day. Simple as the narrative is, it has a touch of the graphic; many New England characteristics come out in it.

Under all, from the right point of view, are the elements of the supernatural. Did the hard-headed old official see and find them? Or did he supply them for his expected market? Why did not he, — and the minions of the law always, — shrink from encountering the wrath and vengeance of the mysterious powers of darkness and the dread possibilities involved in braving them? Did civil responsibility and devotion to duty outweigh natural fears? Or were the men after all rank unbelievers in the delusion? One might spin out any number of questions, psychological and otherwise, wound up in this old yarn. The paper might be made a fruitful text for a profitable sermon.

William Arnall of Redding forty three years of age or thereabouts testifieth and Saith, that on ye Sabbath day last being the 4th Instant 7br: 92 early in ye morning being [Commanded?] by ye Constable of said Redding J[ohn?] Parker [ ] to assist him in the Execution of his office pursuant to a [warrant] from Major Wm Johnson Esqr to apprehend Elisabeth Colson &c. under Suspicion of ye Sin of Witchcraft Then they Coming to ye house of Widow Dastin the Constable opening ye out most dore, and finding ye inner doer fast that he Could not gett in, Called me to him and Said he Could not gett in and as soon as [I Came21] I Came to him we heard ye back dore open then I ran behind ye house & [shee1] then I saw said Elisab: Colson run from ye back dore and gott over into John Dixes feild and I called to her being not far from her, and asked why she ran away for I would Catch her. She said nothing, but run away and [at last1] quickly fell down and got againe and ran again shaking her hand behinde her as it were strikeing at me, and I ran and seeing I could not gaine ground of her, I sett my dog at her, and he ran round about her, but would not touch her, and rining litle further there was a stone wall and on ye other [bushe1] side of it a few bushes yt tooke my sight from her a litle, being but litle behinde her and when I came up to said Bushes I lookt into them, and [Could1] Could see no thing of her, and running on further there was great Cat Came running towards me, and stared up in my face, being but a litle distance from me, near a fence. I Endeauoured to sett my dog [up1] upon her, and ye dog would not minde her but went ye Contrary way, and on I offering to strike at her wth my stick she seemed to run under ye fence, and so disappeared, and I could get sight of maid nor Cat neither any more. Spending some litle time looking about for her & further Saith not

William Arnall

7br. 10th: 92

[Endorsed]

Wm Arnollds Euid22

The other paper is a Writ of Habeas Corpus, which tells its own story. It seems to be not the writ so often styled the bulwark of liberty, bringing up persons assumed to be unjustly in restraint or confinement, with a view to their deliverance, but a writ to bring persons confined in the Middlesex jail before the proper tribunal in another county, for a trial or final disposition of the cases. It runs as follows:

It runs as follows:

Province of the Massachusets Bay in New=England

Midx̣̣ sst William and Mary by the Grace of God King and Queen of England Scottland France and Ireland Defendṛ̣ of ye Faith &c. to the Sheiriffe of the County of Midlesex Greeting Wee Command you that you haue the Body of Lidia Dastin of Reading widow Sarah Dastin single-woman Mary Coulson widow Elizabeth Colson single wõ: all of Reading and Sarah Cole of Lyn in the prison of Cambridge vnder yor Custody as tis said Detained, and vnder safe and sure Conduct together wtḥ̣ the cause of their Caption vnder what name or names soever the said Lidia Dastin Sarah Dastin Mary Coulson Elizabeth Coulson and Sarah Cole, be Censured, in the same before oṛ̣ Justices of oṛ̣ Court of Assize and Goal Delivery at Salem in oṛ̣ County of Essex in oṛ̣ Province of the Massachusets Bay in New-England vpon Tusday the 3ḍ̣ Day of Janñ next in ye fourth year of oṛ̣ Reigne To Do and receiue all and Every of those things wcḥ̣ the Justices of oṛ̣ Court shall Consider of in that behalfe. And then and there you haue this Writt Wittness William Stoughton Esqṛ in Boston the 31st Decemb̃. In ye fourth year of oṛ̣ Reigne Annoq Dom̄. 1692

Jona̱̣ Elatson, Cle͠r:

By Vertue of this Writt I haue hear Brought ye Bodyes of those Persons within Spesefyd and Deliuerd hear att Salem to the under Sheriffe

Per me Timo Phillips Sheriffe for Mid͞dx

[Endorsed]

The Returne of ye Habes Corpus from ye [Sher23] Sheiriffe of Midlesex24

Three of the persons named in the Writ were tried, as appears by the following:

Sarah Cole Verdict “That the said Sarah Cole was Not Guilty of the felony by Witchcraft for wcḥ̣ shee stood Indicted in and by the said Indictment The Court Order the said Sarah Cole to be discharged paying her Fees.”

In the cases of Lidiah Dastin and Sarah Dastin, was the same verdict.25

What disposition was made of Elizabeth Colson or of Mary, does not appear from the records contained in this volume.

The second series of papers concerns the case of Philip English and his wife Mary — a sort of aftermath, at the end of some fifty years, of a case somewhat famous from certain circumstances connected with it. Upham gives “some explanation of the causes that exposed Mr. English to hostility,” and some of the evidence offered against him. He was one of the leading citizens, and “having many landed estates in various places, and extensive business transactions, he was liable to frequent questions of litigation.”26 That he was involved in lawsuits and a hard and persistent fighter, the Court records plainly show. One of the suits was concerning the bounds of a piece of land in Marblehead, and his adversary there was later active in bringing accusations of witchcraft against him. Mary English, wife of Philip, was one of nine named in warrants issued April twenty-first; all to be delivered to the magistrates “for examination at the house of Lieutenant Nathaniel Ingersoll, at about ten o’clock the next morning, in Salem Village.”27 She was committed to prison. On April thirtieth, a warrant was taken out against English and several others; it bears the endorsement: “Mr. Philip English not being to be found,” signed by the initials of the Marshal.28 Why he was not found appears in one of this series of papers. On the sixth of May a warrant was procured at Boston, to the Marshal-General or his lawful deputy to apprehend him wherever found within the jurisdiction and convey him to the custody of the Marshal of Essex. Mr. Upham’s account29 says he was delivered to the Marshal of Essex on the thirtieth of May and after examination before the Magistrates the next day committed to prison; that he and his wife escaped from jail and found refuge in New York until the proceedings were terminated, when they returned to Salem and there continued to live; and that the wife survived but a short time the shock of the accusation, the dangers to which she had been exposed, and the sufferings of imprisonment. Their social position was of the highest. He was a merchant of large estate, extensive business, and owned fourteen buildings in town, a wharf and twenty-one vessels; she a lady of eminent character and culture, the only child and heir of Richard Hollingsworth. Upham’s history has for the frontispiece of the second volume a picture of the English house. The autographs given indicate the character attributed to them.

In his Supplement Mr. Upham30 gives a record of Court showing an adjustment of the accounts of George Corwin, High-Sheriff of Essex, and an order discharging him from all liabilities imposed upon him by reason of the Sheriff’s office, passed 15 May, 1694; and further says that later Mr. English compelled the executors of the Sheriff to pay over to him £60. 3s. In May, 1709, an address was presented to the General Court for the passage of an Act to restore the reputations of the sufferers by the witchcraft persecution and reparation for the damages suffered by their estates, signed by Philip English and twenty-one others. The Act of 2 November, 1711, gave relief, not general, but only to such as had petitioned.31

What gave interest to the case of English was its peculiar circumstances,— the standing of the parties, the causes that may have led to his prosecution, the fact that it was never brought to trial, and especially his hiding and concealment and ultimate escape.

The two papers given here bear upon the last point. They are found in a case contained in the Suffolk Files, brought in 1738 against the then representative of English, by the representative of the man who befriended him at the time of his arrest and imprisonment, to recover for the expenses then incurred. The case itself is merely for the recovery of a debt, and only these two papers have any direct connection with the witchcraft episode, and explain some incidents then in question. They are both Depositions used in evidence in the case and bear the underscoring of counsel to mark important facts therein.

The first is as follows:

Margaret Casnoe of Lawfull Age Testifieth & saith that in part of the Time when there was so much talk of the Witchcraft in this Country and severall persons suffered therefor being according to [the best of32] this Deponents Rememberance about forty five years agone this Depont then being about Eighteen years of Age Livd with Mrs Margaret Pastre In the House & Family of Mr George Hollard in Boston and at that Time Mr Philip English of Salem and his wife being under Suspicion for the aforesaid Crime She was then taken up and put into Boston Goal & he the sd Mr Philip English came to Boston & Requested the aforesd [Mr33] George Hollard to take him into his House who accordingly did & maintaind him there Secretly for some Time & the sd Hollards house being searched for the sd English he was hid behind a bag with Dirty Cloths by which means he Escaped then being taken and afterwards when he was put into prison for Witchcraft & his Estate and Effects thereupon Seizd sd Mr Hollard Supported Said Mr English & his Wife in Goal & this Depont often & frequently carried victuals & provisions from sd Mr Hollards house & by his orders deliverd the same to the sd English & his Wife in prison. And the sd Englishes Family wanting Subsistance when brought up to Boston his Effects being seizd this Depont well Remembers that Mrs Mary English Daughter to sd Philip English Livd at sd Mr George Hollards and was by him maintained & Supported for a Considerable Time (this Depont is not Certain how long) But sd Mr Hollard maintaind & Supported the sd Mary English for a Considerable Time after the Rest of said English’s family were gone from Thence

|

Sig |

||

|

Margaret |

× |

Casnoe |

Boston July 8th 1738

Sworne to in Infṛ̣ Court

Boston 18 July 1738

Attr Ezekl Goldthwait Cler.

A True Copy Examd.

Per Ezekl Goldthwait Cler

[Endorsed]

Casnoes Depocoñ34

The second Deposition runs thus:

Salem Febỵ̣ 12, 1738

Susanah Touzel [of ful Age Testyfyeth &35] Saith that [in the year 169236] she was carried from Her Father Phillip Englishs House To Mṛ Arnolds the Goal Keeper and livd there wṭh my Father Phillip English & Wife while they continued there and when they left the Goal She was carried to Capṭ Jno Aldens to Board and Continued there till the sd Phillip English and Wife returnd from N York to their own Dwelling in Salem and then they Sent for her home

Susanna Toczel

Essex ss. Salem Feb: 12th 1738

Then Mrs Susa͠nah Towzell (who by reason of Sickness & bodily Infirmity is incapable of Traveling to Court) made oath to the truth of the within Deposition She being carefully Examined & Cautioned to Declare the whole Truth, (The Adverse party whom this may Concern, living more than Twenty mile not being notifyed)

Jurat Coram

Bene Lynde Junr Just Pacs

[Endorsed]

Susa͠nah Towzells Deposition

Taken before Bene Lynde Jṛ̣37

Not as strictly germane to these papers, but as connected with the general subject and having some bearing upon considerations already offered, it may not be out of place to add a memorandum showing the history of witchcraft as it appears in the records of the highest Court of Massachusetts. It is not intended to touch here upon the trials held in the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer created nominally under the new Charter, but whose validity has been well questioned. A full account of its creation and its doings is to be found in Washburn’s Sketches of the Judicial History of Massachusetts.

The Records of the Court of Assistants, extant and accessible, from 1630 to 1673 are few and incomplete. In these no case of witchcraft is found. One case, however, said to be the earliest, that of Margaret Jones of Charlestown convicted and executed in 1648, is mentioned by Winthrop.38 Another is that of Anne Hibbins in 1656, memorable in its circumstances and for the controversy which occurred between the Bench and the Jury. The Jury found her guilty, the Magistrates refused to accept the verdiet. The case was carried to the General Court; popular clamor was effective and she was convicted and executed.39 William F. Poole says that twelve persons were executed in New England before 1692, six of whom were in Connecticut. Besides the two previously mentioned, Jones and Hibbins, he gives the cases of the wife of Henry Lake of Dorchester in 1650, Mary Parsons, wife of Hugh, of Springfield in 1651, and of a Cambridge woman at about the same time. He also has the case of Goody Glover of Boston, in 1688.40 Rather curiously the last case does not appear in the Records of the Court of Assistants, 1673 to 1692, nor is it in the Massachusetts Colony Records. There are some dozen papers touching on witchcraft in the early Suffolk Court Files, between 1652 and 1666, and a large number in 1692 and shortly after. The Records of the Court of Assistants from 1673 to 1692 are full and complete. In this volume six cases appear.

In 1673 Anna Edmonds was “Complajned on by Samuell Bennett & his wife on suspition of witchcraft After the Court had heard all the euidences produced against her the Court declared that they saw no Ground to fix any charge against her & so dismist hir,” ordering the complainants to “pay the charges of the wittnesses in ye case = thirty shillings & ffees.”41

In the next year was the somewhat famous case of Mary Parsons of Northampton, recorded at length, with the result that “the Jury . . . found hir not Guilty = & so she was dischardged.”42

In 1680 Elizabeth Morse was indicted for “not hauing the feare of God before hir eyes being Instigated by the diuil & hauing had familiarity wth the diuil contrary to the peace of our Souaigne Lord the King his croune & dignity ye lawes of God & of this Jurisdiction,” tried and found “Guilty according to Indictment & had sentenc.”43 There is a hint of unwritten pathos about her case, for the next year in answer to a petition of her husband and to her own, “The Court Judgeth it meet to Repreive the sajd Elizabeth morse the Condemned prisoner to the end of the next session in Octobe, and in the meantime order hir dismission from the prison in Boston to Returne home wth hir husband to Newbery Prouided she goe not aboue sixteen Rods from hir Oune house & land at any time except to the meeting house in Newbery nor remoove from the place Appointed hir by the minister & selectmen to sitt in whilst there.”44 Her name does not appear thereafter and it may be hoped the reprieve was final.

Another case in 1680 was that of “Mary Hale of Boston widow” indicted “for that yow not hauing the feare of God before yor eyes and being Instigated by the divill hauing had familiarity wth him by the abhorred sin & art of witchcraft did kill & bewitch one [Michael] Smit to death,” and found “Not Guilty according to Indictment”45

There were two cases in 1683. James Fuller of Springfield was indicted for familiarity with the devil. He seems to have made a confession, but on being brought to trial, “After the Indictment & euidence produced against him was Read he owning the charge as sajd by him but denyed the trueth of it saying he had belyed himselfe his examination & [confession being] committed to the Jury,” they found him “not Guilty according to Indictment.” He was not, however, to go scot-free. “The Court Consi[der]ing of his wicked & pernicious willfull lying & Continuanc in it till now putting the Country to so great a charge sentenct the sajd James ffuller to be seuerely whipt wth thirty stripes seuerefy lajd on & that he pay hue pounds mony to the Tresurer of the Country to dischardg the chardges of his triall paying fees of Court stands Committed till the sentence be pformd. and that in Case ye sd fiue pounds be not pd by ye sd ffuller wthin a month Its left wth ye Tresurer of ye Country to ship him of & dis̃pose of him as he Cann not exceeding fower yeares to Ansr the charges.”46 Later in the year Mary Webster of Hadley “hauing binn presented for suspition of witchcraft . . . & left to further Tryall” was “brought to the barr” and indicted for having “as in & by seuerall testimonjes may Appeare” had familiarity with the devil “in the Shape of a warraneage,” and the existence of the secret infallible physical signs are set forth.47 The jury, however, found her not guilty. The use in the charge of the Indian name for a black cat “warraneage” is interesting and suggestive in several ways.

No case of witchcraft appears between 1683 and 1692; and the issue of the six cases given above is noticeable — all trials in the Colonial Court of Assistants.

This Court was succeeded in the time of the Province by the Superiour Court of Judicature. In the first volume of its Records, 1692–1695, the following cases of witchcraft appear:

Superiour Court of Judicature, Court of Assizes & Generall Goal Delivery, holden at Salem in the County of Essex, Province of Mass. Bay in New England in America, 3 Jan. 1692–3

Present.

|

The Honbḷ̣e William Stoughton Esqṛ Chief Justice. |

||

|

Thomas Danforth Esqr |

|

John Richards Esqr |

|

Wait Winthrop Esqr |

Samuel Sewell Esqr |

|

In over fifty cases before it, the Grand Jury ignored the majority and only twenty-one persons were tried and indicted for felony by witchcraft, with the results given:

|

Rebekah Jacobs wife of George Jacobs of Salem. |

|

|

|

|

Margaret Jacobs of Salem single woman. |

|

||

|

Sarah Buckley wife of Wm. Buckley of Salem. |

|

||

|

Mary Witheridge of Salem. |

|||

|

Job Tookey of Beverly. |

|||

|

Hannah Tyler of Andover. |

Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees. |

||

|

Candy a Negro servant to Mrs. Mary Hawkes of Salem |

|

||

|

Mary Marston wife of John Marston Junr. of Andover |

|

||

|

Elisabeth Johnson of Andover. |

|||

|

Abigaill Barker wife of Ebenezar Barker of Andover |

|

||

|

Mary Tyler wife of Hopestill Tyler of Andover |

|

||

|

|

The Court ordered the Keeper of the Goal to take care of the prisoner, according to law. |

||

|

Sarah Hawkes of Andover. Not Guilty. |

|

The Court ordered Mary48 Hawkes aforesaid to be discharged, paying her fees. |

|

|

Marcy Wardwell of Andover. Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees |

|||

|

Elisabeth Johnson, Junr. of Andover. Guilty. |

|

The Court ordered the Keeper of the Goal to take care of the prisoner according to law. |

|

|

Mary Bridges wife of John Bridges of Andover |

|

Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees. |

|

|

Mary Post of Rowley. Guilty. |

|

The Court ordered the keeper of the Goal to take care of the prisoner according to law. |

|

|

Hannah Post of Boxford |

|

Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees. |

|

|

Sarah Bridges of Andover. |

|||

|

Mary Osgood wife of Capt John Osgood of Andover |

|

||

|

Mary Lacey Junr. of Andover. |

|||

There were three convictions and eighteen acquittals.

At the term of the Sup. Court of Jud. &c. held at Charlestown in the County of Middlesex, 31 Jan. 1692–3.

Present.

-

- William Stocghton, Esqr. Chief Justice.

- Thomas Danforth, Esqr.

- John Richards, Esqr.

- Wait Winthrop, Esqr.

- Samuel Sewell, Esqr.

|

Mary Toothaker of Billerica. |

|

Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees. |

|

|

Mary Taylor of Reding wife of Sebread Taylor |

|

||

|

Sarah Cole wife of John Cole of Lynn |

|

||

|

Lidiah Dastin of Reding. |

|||

|

Sarah Dastin of Reding. |

The last three cases are referred to in connection with the paper on Elizabeth Colson.

Sup. Court of Jud. &c. held at Boston for the County of Suffolk 25 April 1693.

Present.

-

- William Stoughton, Esqr.

- Chief Justice. Thomas Danforth, Esqr.

- John Richards, Esqr.

- Samuel Sewell, Esqr.

John Alden of Boston, “suspition of Witchcraft,” appeared and was discharged by proclamation.

Sup. Court of Jud. &c. held at Ipswich, May 1693.

Present.

-

- Thomas Danforth, Esqr.

- John Richards, Esqr.

- Samuel Sewell, Esqr.

|

Susanah Post of Andover. |

|

Not Guilty. Discharged by paying fees. |

|

|

Eumice Frie of Andover wife of John Frie |

|

||

|

Mary Bridges, Junior, of Andover. |

|

||

|

Mary Barker of Andover. |

|||

|

William Barker, Jr. of Andover. |

Of the thirty-two persons tried in the Superiour Court of Judicature,— twenty-six in Essex, five in Middlesex, and one in Suffolk, — twenty-nine were acquitted and three found guilty, the last all in Essex. In the second volume, which brings the Records of this Court down to 1700, no case of witchcraft is found. The year 1693 practically closed the judicial history.

Mr. Andrew McFarland Davis called attention to the use of the words “The Rhode Island Land Bank” in the printed Transactions of the February meeting, 1900 (VI. 380). The same words are used in the Table of Contents of the volume. The Index also has an entry, “Rhode Island Land Bank.”

The Rhode Island “banks” referred to in the paper submitted at that meeting were mere emissions of Colonial currency, which were loaned to citizens, hence the name “banks.” They were not what is generally understood by the term “Land Bank.” The use of the word “land” as a descriptive epithet in connection with these banks is, therefore, to a certain extent misleading.

Mr. Thomas Minns spoke of the service on the previous evening at the First Church in Boston, in dedication of six mural tablets that have recently been placed there in memory of Governor John Endicott, Anne Hutchinson, Sir Henry Vane the younger, Governor John Leverett, Governor Simon Bradstreet, and Anne Bradstreet, all of whom were members of that Church.

Mr. Noble read a letter from Dr. Daniel Coit Gilman, a Corresponding Member, presenting to the Society a set of the Fund Publications of the Maryland Historical Society and a set of the Archives of Maryland. The gift was gratefully accepted.

Mr. Horace Everett Ware of Milton was elected a Resident Member.

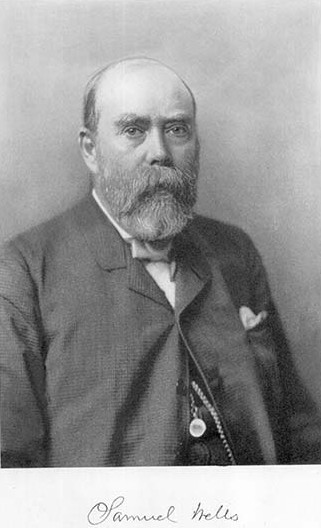

Dr. Charles Montraville Green communicated a Memoir of Samuel Wells, which he had been requested to prepare for publication in the Transactions of the Society.

Engraved for The Colonial Society of Massachusetts from a portrait from life

MEMOIR OF SAMUEL WELLS, A.B.

BY CHARLES MONTRAVILLE GREEN

Samuel Wells died at his home in Boston on Saturday, 3 October, 1903. Only two days previously he had returned from his summer home at Campobello. Although his health had been somewhat impaired for several years, it had improved so much that he had resumed many of his professional duties and social relations, and his death was entirely unexpected.

Mr. Wells’s father, Samuel Wells, descended from the early settlers of New Hampshire, where he was born in 1801; but in early life he removed to Hallowell, Maine, and thence, in 1844, to Portland, where he practised law. From 1848 to 1852 he served as a Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Maine, and in 1856 and 1857 Judge Wells was the Governor of his adopted State. Soon after his service as Governor, Judge Wells removed with his family to Boston, where he practiced law until his death, 15 July, 1868. He married Louisa Ann Appleton, a daughter of Moses Appleton of Waterville, Maine, a descendant of the Appleton family which came early to Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Samuel Wells was born in Hallowell, 9 September, 1836. He fitted for college in a private school in Portland, and in 1853 entered Harvard, where he graduated with high rank and received his A. B. with the Class of 1857; he also won the distinction of membership in the Harvard Chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa. He then studied law in his father’s office in Boston, and was admitted to the Suffolk Bar in 1858. He continued in practice with his father until the death of the latter in 1868; three years later he formed a partnership with the late Edward Bangs. The firm of Bangs and Wells has survived the death of both original members, and now comprises the eldest son of each.

On 11 June, 1863, Mr. Wells married Kate Boott Gannett, daughter of the Rev. Ezra Stiles Gannett, D. D., for many years minister to the Arlington Street Church in Boston. Three children were born to them: Stiles Gannett, Samuel, junior, and Louisa Appleton; Samuel, junior, died several years ago.

Mr. Wells engaged successfully in the general practice of the law, and was acknowledged to be one of the leading members of the Boston Bar, — able, judicious, and reliable in his judgment. He achieved success through his intellectual ability, sound judgment, and great industry; and for more than forty years of professional life held the confidence and respect of the community. Early in his career he became interested in fiduciary and corporation law; he was a trustee of many important estates, and assumed the care of a large amount of real and personal property. He formed plans for the combination of capital in the erection of large business blocks and office buildings; many trusts and associations, which have been established for this purpose, have been organized upon principles which he proposed. The State Street Exchange, established in 1886, was the earliest of these organizations, and he was its President for several years. He was actively connected with the Boston Real Estate Trust, the Bromfield Building Trust, the Municipal Real Estate Trust, the Winthrop Building Trust, the Washington Building Trust, and with other similar associations. He was first Vice-President and Director of the John Hancock Mutual Life Insurance Company, and for several years counsel of the corporation. He also served as a Director of the Boston Storage Warehouse Company, and of the Mercantile Fire and Marine Insurance Company.

Although he never held political office, Mr. Wells took an active interest in public affairs and in the promotion of good government: he attended caucuses and political conventions, and served on committees. He was a member of the Tariff Reform League, and of the Citizens’ Association of Boston; in 1884 he served on the general committee of the latter association for the amendment of the City Charter.

Aside from his professional career, Mr. Wells had many other interests. It was a surprise to friends of his later life to learn that for many years he had quietly spent leisure hours in the study of natural history. In middle life he devoted much time to microscopy and micro-photography; he made a special study of diatoms, and prepared a valuable collection of microscopic slides; his knowledge of this subject has been recognized in this country and in Europe, through his contributions to scientific journals. He was a member of the Boston Society of Natural History, and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. He took an especial interest in the study of English and Colonial history; he was fond of collecting books relating to the City of Boston and her public men. This taste for historical and genealogical study led him to become a member of the Bostonian Society, the Bunker Hill Monument Association, and the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

With these tastes and his well-known personality it is natural that he should have been selected for membership in the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, to which he was elected at the first Stated Meeting of the founders in January, 1893. During his ten years’ fellowship with us Mr. Wells was always an interested member, and attended the meetings of the Society with some regularity when in Boston, and when his health permitted. He was a warm personal friend of our first President, Dr. Benjamin Apthorp Gould; and at the Memorial Meeting which this Society held after Dr. Gould’s death, Mr. Wells, in the unavoidable absence of the Vice-Presidents, was asked to preside. He paid an affectionate tribute to Dr. Gould’s memory, inspired by years of friendship and fraternal association.

A man of kind and generous impulses, Mr. Wells gave much time from his busy life to the interests of philanthropy and charity. In 1867 he joined with others in reviving the work of the Boston Young Men’s Christian Union, and for several years served as Treasurer and as a Director in that institution; at the time of his death he was one of the trustees of its permanent fund. He was also a trustee of the Boston Lying-in Hospital, and of the building fund of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union. In 1890 he became a member of the Massachusetts Charitable Fire Society, and since 1899 had served on its Board of Government.

Mr. Wells was fond of club life and of social intercourse with his fellows. He was an active member of the Union Club, the Unitarian Club, St. Botolph Club, Papyrus Club, the Boston Art Club, the Beacon Society, the Exchange Club, of which he was a founder and the first President, and of the University Club of New York. On leaving college he became a member of the Jacobite Club, a social organization of the class of 1857 that brought its members into relations of close intimacy and attachment.

No memorial of Mr. Wells would be complete without reference to his deep and abiding interest in Freemasonry, to which for many years he gave a considerable portion of his time. He received his first three degrees in Revere Lodge of Boston in 1862 and 1863, and served that Lodge as Master in 1873 and 1874, and subsequently for nine years as Treasurer. He became a member of the First Worshipful Masters’ Association in 1873, and was its President from 1876 to 1881. He was Grand Treasurer of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, A. F. and A. M., from 1879 to 1887, Deputy Grand Master in 1888 and 1889; and in 1890 he attained the highest masonic honor in Massachusetts, serving as Grand Master for three years. He received the capitular degrees in St. Andrew’s Royal Arch Chapter in 1865, and the same year was created a Knight Templar in St. Bernard’s Commandery of Boston, serving as Eminent Commander in 1871 and 1872. In 1875 and 1876 he received the grades of the Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite, from the fourth to the thirty-second degree, and in 1890 he was made a member of the Supreme Council and received the thirty-third and last degree. He was greatly loved and respected by his masonic brethren, among whom he moved for forty-one years.

The funeral service of Mr. Wells was held October sixth in the Arlington Street Church, of which he had long been a member; it was conducted by the minister, the Rev. Paul Revere Frothingham, and by the Rev. Edward A. Horton, Junior Grand Chaplain of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts. Classmates, colleagues, friends, and fraternal associates gathered to show by their presence the love and esteem they bore for him who had entered so fully into their lives.

Mr. Wells was a man of many interests; he lived a full life. His industry and legal learning, his sound judgment and strict integrity, brought him eminence in his profession and in important corporate interests. His faithful and devoted labor in philanthropic work won for him the grateful esteem and respect of all who worked with him and of all for whom he worked. In his more formal relations his demeanor was quiet and reserved; but in the companionship of his friends who knew him well, he had a cheerfulness and ready wit, a spirit of kindliness and helpfulness, that endeared him to all who were so fortunate as to enjoy his intimate acquaintance.

Comt.

Comt.

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly

By Order of the Great and General Court or Assembly