113. Ninigret, Sachem of the Niantics, portrait in oils

Prints of the American Indian, 1670–1775

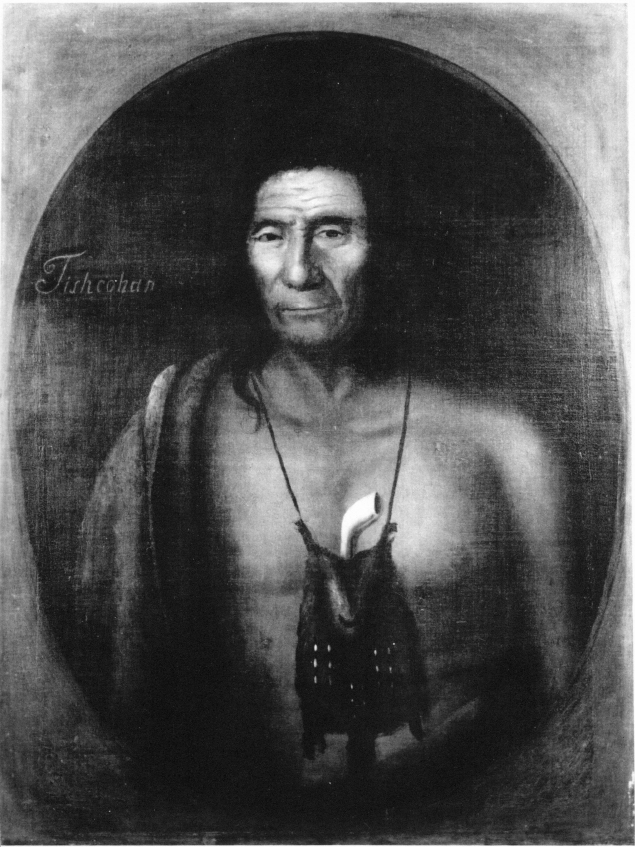

PERHAPS not strangely, Americans, prior to the opening of the West, showed very little interest in depicting the Indian. So far as I know, only four portraits of Indians were painted in this country before the American Revolution: the portrait of Ninigret, sachem of the Niantics, by an unidentified artist, which descended in the Winthrop family and is now in the Rhode Island School of Design Museum Of Art; the portrait of the Rev. Samson Occom, Eleazar Wheelock’s Indian preacher, by Nathaniel Smibert, now in the Bowdoin College collection; and the portraits of Tishcohan and Lapowinsa, Delaware Indians who had taken part in the notorious “walking purchase” of Indian lands, painted by Gustavus Hesselius for John Penn in 1735 and now in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

But, on the other side of the Atlantic, where the American Indian was a curiosity rather than a frequent enemy, the interest in what he looked like was considerably greater. He was still the exotic which had captured the fancy of the early explorers. These explorers who came to the southeastern Atlantic region of what is now the United States made the earliest pictures of American Indians: Jacques Le Moyne with the ill-fated expedition of Laudonniere in 1564, and John White with Raleigh’s first Virginia colony in 1585 and 1587.

Only one of Le Moyne’s paintings is known to have survived; it is presently in the New York Public Library. But Theodore De Bry, with his sons and one G. Veen, made engravings of forty-two of them to illustrate De Bry’s publication of an account of Laudonniere’s Florida settlement. Similarly, De Bry engraved the John White drawings and watercolors for his Virginia “voyage.”

The De Bry engravings, since they date from 1590, are actually too early for the scope of this paper, but I have spoken of them here because they constitute the first, and earliest, of several “families” of Indian iconographies into which I think the engravings of American Indians made prior to 1775 can be divided.

114. Samson Occom, portrait in oils by Nathaniel Smibert

115. Tishcohan, portrait in oils, 1735, by Gustavus Hesselius

116. Lapowinsa, portrait in oils, 1735, by Hesselius

117. Chief Athore and René de Laudonnière, miniature in gouache, 1564

The three family genealogies—if you will permit me to use that term—are as follows:

1) The De Bry engravings based on the work of Le Moyne and White.

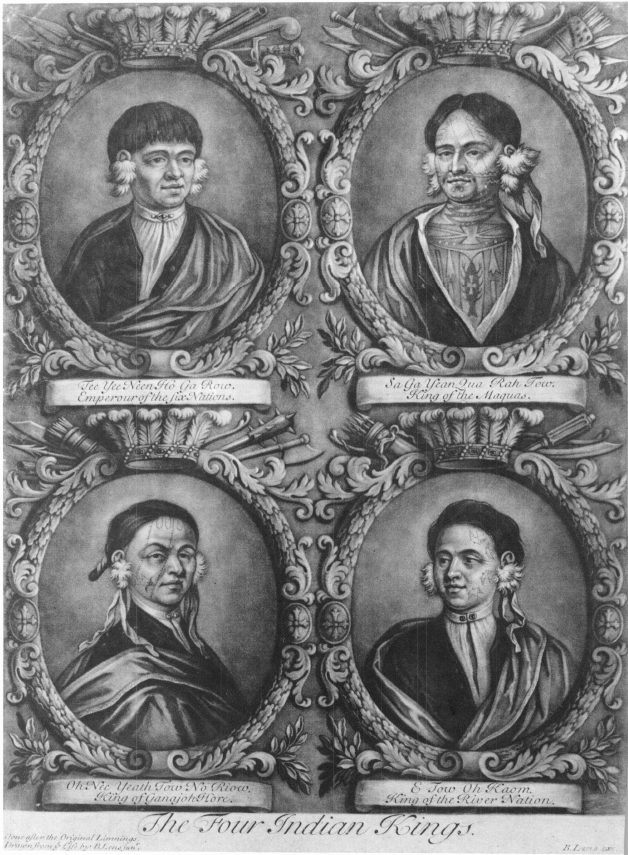

2) The engravings based on John Verelst’s paintings of the “Four Kings of Canada” (as they were erroneously called), made when these Indians visited London and the Court of Queen Anne in 1710. This family includes a considerable progeny—not all of whom are strictly legitimate, as we shall see—and it also includes two collateral branches: the Bernard Lens prints based on the miniature paintings by Bernard Lens, Jr., and the prints by John Faber, Sen., from his own paintings. The Lens prints left no issue, but Faber’s prints were used as models by Peter Schenck, a German artist working in Amsterdam, who issued a set of oval bust portraits of the Indians: they are the Faber portraits reversed.

118. Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row by Simon after Verelst, 1710

119. Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, by Simon after Verelst, 1710

120. Etow Oh Koam, by Simon after Verelst, 1710

121. Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, by Simon after Verelst, 1710

122. The Four Indian Kings by Bernard Lens after miniatures by his son, 1710

123. On Nee Yeath Tow no Riow by Faber, 1710

124. Sa Ga Yean Qua Rash Tow by Faber, 1710

125. E Tow O Koam by Faber, 1710

126. Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row by Faber, 1710

127. On Nee Yeath Tow no Riow by Schenck after Faber

128. Sa Ga Yean Qua Rash Tow by Schenck after Faber

129. E Tow O Koam by Schenck after Faber

130. Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row by Schenck after Faber

3) The group of prints inspired by the visits of Southeastern Indians, Cherokees and Creeks, from the Carolinas and Georgia to London in 1730, 1734, and 1762. The relationships between these prints is somewhat tenuous and perhaps I am stretching a point to classify them as a family.

Lastly, to these three categories we should add a fourth, which we might label “Waifs and Strays,” although in some instances a little crossbreeding between the classifications I have already set up can be discerned. This fourth category includes not only the earliest American depictions of the Indian in prints but also the fanciful images we find as decorations in books, in the cartoons of the period, and in cartouches on maps. It is mainly a catch-all classification.

Returning briefly to the Le Moyne–White–De Bry tradition, let me point out that although these prints display the clothing, accoutrements, and habits of the Indians—their modus vivendi, or, as we might say today, their life-style—the figures themselves are not so much American Indians as they are classic, post-Renaissance nudes. They are very much in the tradition of European art of their time, rather than anthropologically and ethnologically correct. There is no strong feeling that we are seeing real Indians, such as we have when we look at the John White watercolors. Rather it is a sophistication of the material, as if these were European men and women, tinted a little, perhaps, to give them a superficial “redness,” but still very much within the “noble savage” visual concept.

The De Bry iconography persisted for a long time. We encounter it, for instance, as late as 1705, in Robert Beverley’s The History and Present State of Virginia, . . . where the fourteen engraved plates by S. Gribelin are reduced copies of the De Bry engravings. These same plates appear to have been used in the second edition of the Beverley History in 1722. The dates of both editions are well within the time span of this study, testifying to the enduring qualities of De Bry’s image of the Indian.

The image continued to have a considerable longevity. We find such classical Indian figures used to symbolize Britain’s American colonies well into the second half of the eighteenth century. One such example is the print entitled “British Resentment, or the French Fairly Coopt at Louisburg,” done at London in 1755. In this print drawn by Boitard and engraved by J. June, Britannia is receiving into her protection a male and a female Indian, very much in the De Bry tradition, who represent Britannia’s “injured Americans.”

I would like to pass now to my third classification, Cherokees and Creeks in London, and take up the problems of the Four Kings of Canada later.

It was when Indians began to visit London that their graven image, so to speak, changed radically. This is very noticeable in the prints of the Four Kings of Canada, who went to London in 1710, and it is also easily discerned in the print of seven Cherokees, a copperplate engraving by James Basire after a painting by Markham, which was undoubtedly issued during their visit in 1730.

Even with pants on, and wearing English coats with frogs of gold braid, these men are clearly Indians.

The seven were brought over from Carolina by Sir Alexander Cuming “to enter into Articles of Friendship and Commerce with His Majesty,” as it states on the print itself. The treaty was presented to them on September 7, 1730, and signed two days later.

The next Indian visitors to London were the Lower Creek chief Tomochichi, his wife Scenawki, his young nephew Tooanahowi, and several others who accompanied Oglethorpe to England in 1734. Their visit is commemorated in the group painting, “The Founding of Georgia,” by William Verelst, which is now at Winterthur. In the lower right corner of this painting can be seen Tomochichi’s nephew with his bald eagle and what appears to be a black bear cub.

The eagle reappears in a painting of Tomochichi and the lad done by William Verelst which was made into a mezzotint engraving by John Faber. The boy is holding the eagle this time, and his uncle is wrapped in a fur robe.

132. [Seven Cherokee chiefs], c. 1730

The original painting used to hang in the rooms of the Georgia Trustees in London, but Chaloner Smith reported it “now lost” when he published his work on British mezzotint portraits in 1878.

Another version of this double portrait appears as a rather crude engraving by the German, Joh. Jacob Kleinschmidt, after Faber, which was used as a frontispiece in Urlspeger’s Ausfuhrliche Nachricht von den Salzburgischen Emigranten (Halle, 1735).

Another Cherokee chief, Cunne Shote, was in the embassy from this tribe which arrived in London from South Carolina in 1762. His portrait was painted by Francis Parsons and made into a mezzotint engraving by James McArdell. Just when the print was actually issued I cannot say, but in 1763 Parsons was represented at the Society of Artists’ exhibition in Spring Gardens by portraits of an Indian chief and of Miss Davies, the actress. The Indian was probably Cunne Shote.

133. [Oglethorpe presenting Tomochichi and others to the Trustees of Georgia]

134. A detail, showing Lower Creek Indians who accompanied Oglethorpe to England

135. Tomo Chachi Mico and Tooanahowi, by Faber after Verelst, c. 1743

In the portrait he is shown wearing a gorget engraved with the initials of George III, a silver amulet on his right arm, medals at his throat, and a feather in his hair. In his right hand he holds a scalping knife.

In the DeRenne Library collection of Georgia material there is a French version of this Cunne Shote portrait. It is described in the DeRenne catalogue as a copper engraving, colored, and bearing the legend: “Cunne Shote, Chef des Chiroquois, d’apres Parson.” It was issued at Paris, chez Duflos, rue St. Victor, and is described as a full-length portrait with scalping knife in right hand, 11 by 8⅝ inches. For some reason not apparent to me the DeRenne catalogue dates it “circa 1780?”

There is one more print in the Cherokee series, but I shall postpone discussion of it until after we have talked about the Four Kings of Canada.

Fortunately for scholarship, R. W. G. Vail cleared up the whole problem of these portraits in an article entitled “Portraits of ‘The Four Kings of Canada,’ A Bibliographical Footnote,” which he contributed to that festschrift for Dr. A. S. W. Rosenbach, To Doctor R., published in 1946.

Vail pointed out that the earliest states of the mezzotint portraits based on the Verelst paintings were engraved by John Simon, that in the second state Simon’s address was erased from the plate and in its place was engraved the information that it was “Printed & Sold by John King at ye Globe in ye Poultrey, London.” In the third state two and a half centimeters were cut from the top of the plate and three and a half centimeters from the bottom, and a new legend applied. This, in addition to identifying the subject and listing Verelst as the painter and Simon as the engraver, stated that it was “Printed for Jno. Bowles & Son, at the Black Horse in Cornhill London.”

136. Cunne Shote by McArdell, c. 1763, after Parsons

Parenthetically, I would like to state here that the four oval bust portraits by Lens are all on one sheet, two above and two below. The Faber portraits are on separate sheets. I have not seen the Schencks,1 resting content with Vail’s detailed descriptions of these prints. His work is very thorough, giving not only all the necessary physical descriptions but also locations as of that date of copies of all states, and similar information, including a whole bibliography of the subject.

Out of the Verelst-Simon prints came some very interesting developments. It is a widely known fact, which scarcely needs repeating in this company, that Paul Revere was notorious for using the work of others, making his own copies for his own purposes.

Thus, when the time came to produce a portrait of King Philip to be used as an illustration in the Newport, 1772, edition of The Entertaining History of King Philip’s War . . . , Revere turned to Simon’s prints for what we can charitably describe as inspiration or a little more realistically as looking for something to copy.

As I have pointed out in some detail in my little pamphlet entitled An Indian’s an Indian, or the Several Sources of Paul Revere’s Engraved Portrait of King Philip, published by the Rhode Island Society of Colonial Wars in 1959, Revere borrowed shamelessly from the Simon prints of Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow and Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row, presumably on the ground that one Indian looks more or less like another. (Incidentally, I am a movie critic as well as an art critic, and I took my title for that pamphlet from an old Hollywood saying: “A rock’s a rock, and a tree’s a tree. Let’s shoot it in Griffith Park.”)

The upshot of my findings, not to go into detail at this time, was that Revere took the print of Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row and substituted for the bow he held in his left hand a gun and forearm which he extracted from the Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow portrait and reversed.

137. Philip. King of Mount Hope, Revere’s fictitious portrait

But Revere’s borrowing did not end here. For the group of Indians at lower left in the Philip portrait he probably went to a print published in the Court Miscellany and Gentleman and Lady’s Magazine for September 1766. This was a reduced version of a print engraved by Grignion from a Benjamin West painting of Indians conferring with Colonel Henry Bouquet at a council fire near his camp on the banks of the Muskingum in October 1764.

The Grignion print had been made as one of the illustrations in the London, 1766, edition of Bouquet’s account of his expedition against the Ohio Indians. It is perhaps an interesting sidelight to all this to observe that Revere later copied the Court Miscellany print in its entirety for the Royal American Magazine in 1774.

Revere went back to the Simon prints once more—or perhaps only to his King Philip print derived from them—for a small figure of an Indian he engraved on a Massachusetts Bay Colony promissory note in 1775. This time the gun in the left hand has been transformed into a staff surmounted by a liberty cap, and he has eliminated certain details. On the other hand, he has retained the open collar and open left cuff from his earlier print.

Before I take up one more puzzling print, I would like to clear away my fourth category: Waifs and Strays.

The most important of these, the later portraits of King Hendrick, who was one of the Four Kings and known as Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, Emperor of the Six Nations, when he was in London in 1710, have been described by Vail in the article already cited. The portrait of “The brave old Hendrick . . .” in court dress is a charming print. The example at the John Carter Brown Library, which was acquired after Vail had drawn up his list of locations, is colored. It is unfortunate that we do not know either the painter or the engraver of this portrait. It was offered for sale by Elizabeth Bakewell opposite Birchin Lane in Cornhill, and Vail dates it as around 1740, when the sixty-year-old sachem of the Mohawks made his second visit to London. For further details on the King Hendrick portraits I refer you to the Vail article, which is gratifyingly thorough.

Then there is, of course, the Indian on the seal of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay. Such a seal had been cut in England prior to 1629, when it was sent to the colony. A copy is said to have been made by John Hull, the mintmaster, but a woodcut version was made by John Foster, and this is held, in the Middendorf catalogue, to be the earliest American cutting of the seal. If so, it is also the earliest American depiction of an Indian in a print. The earliest known use of Foster’s seal was on a broadside dated October 26, 1675. The seal was superseded in 1684 by one bearing the royal arms.

138. The Indians giving a Talk to Colonel Bouquet, 1766

139. The brave old Hendrick, c. 1740

Two prints of Indians were produced in France at an undetermined date but probably around 1700. One purports to be the King of Albion, or New England, and the other the King of Florida. I believe they are purely fanciful portraits of nonexistent monarchs.

Prints of Indians occur in the volumes of Hulsius, but they, too, frequently seem to be fanciful. Since they are earlier than the starting date of this paper, and since they left no progeny comparable to the De Brys, they need not be considered here. The French exploration under Champlain and others also produced some prints of Indians, but they are not of present concern to us.

Arnoldus Montanus’ The New & Unknown World, to translate its title into English, published at Amsterdam in 1671, contains prints of Indians, but they are all in what might be called the exploration tradition. Some of them, such as the print of Indians dancing on Hispaniola, served to reinforce the classical image of the Indian as noble savage, wearing a crown of feathers.

It would be interesting to trace the longevity of this classical tradition, which was continued by Mallet and Moquet, but that is not my purpose.

We next encounter some prints of Indians in Lionel Wafer’s New Voyage and Description of the Isthmus of America (London, 1699), where Indian life is shown in three plates, of a party setting out, of a medicinal blood-letting, and of a tribal council. But these are Central American Indians and those similarly depicted by Gumilla are South American.

Hennepin and Lahontan wrote books around the end of the seventeenth century which were illustrated with plates showing Indian life and customs but which are totally inadequate as portraits of Indians. The best illustrations of Indian activities around this date were the plates in Lafitau’s Moeurs des Sauvages Ameriquains, published in Paris in 1724. Of doubtful ethnological value, the prints continue to show the strong influence of the classical tradition.2 Interestingly enough, there is some evidence that this edition, though it was in French, was distributed in this country by a Philadelphia bookseller named Pennington. This might mean that the work had some influence on the image of the Indian among upper-class urban American colonials.

140. Le Roy D’Albion, 1680

141. Le Roy De La Floride, 1680

The prints from Lafitau’s work were folded and inserted in this small format edition. In the small folio edition they occupy an entire page. Similarly the prints are on a flat, full page, in a German edition, edited by S. J. Baumgartens, Algemeine Geschichte der Lander und Volker von America, issued at Halle in 1752. They seem to have been struck from the same plates.

Le Page du Pratz, in his Histoire de la Louisiane (Paris, 1758), which was amply illustrated by some forty plates, including two fine, full-length portraits of Indians in summer and winter dress, and depictions of a tribal dance and a buffalo hunt as well as of many Indian customs, gives us a good view of the life of Indians of the Mississippi valley. By and large, I think Le Page du Pratz’ depiction of the Indians’ way of life is the most satisfactory we had between the time of De Bry and the American Revolution.

It seems somewhat extraneous to include the British mezzotint of the Rev. Samson Occom in this listing, since only our knowledge and the legend on the print would tell anyone that this is a portrait of an Indian in the white man’s clerical garb. It was engraved by J. Spilsbury from a painting by M. Chamberlin, and was published September 20, 1768, by Henry Parker in London.

142. The Reverend Mr. Samson Occom by Spilsbury after Chamberlin, 1768

Three Indians appear over the shoulder of Major Robert Rogers, “commander in chief of the Indians in the Back Settlements of America,” in the mezzotint portrait published in London. But the print was published in 1776, a year too late for the period of this paper.

As examples of fanciful depictions of Indians used as book decorations I shall cite only two examples, the armed warrior on the title page of Gallic Perfidy: A Poem, published at Boston in 1758 by Benjamin Mecom, Franklin’s nephew, and the Indians hacking away at helpless colonists in a little woodcut on the title page of The Cruel Massacre of the Protestants, in North America, published at London, probably about 1760.

Lastly, I would like to offer as an example of my main thesis a print which must have been engraved in London in 1762. It is of “The Three Cherokees. came over from the head of the River Savanna to London. 1762. [with] Their Interpreter that was Poisoned.” This print seems to me to tie it all together.

Although these are Cherokees in London in 1762, they are illegitimate offspring—as Paul Revere’s King Philip was later to be—of the Four Kings of Canada and possibly Cunne Shote, and they are betrayed, I might add, by a dog masquerading as a wolf.

In their case, however, the unknown printmaker was a bit more imaginative than Revere in his use of the available material. For instance, he gave them thigh-high leggings instead of mocassins, but quite obviously details in the drapery of their blankets have been borrowed, as well as the positions of arms, hands, and legs, from the Simon prints or the Verelst paintings of the Four Kings. Most remarkable, aside from the tell-tale inclusion of the wolf totem from the print of Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row, is the fact that the pattern of the facial tattoos or painting was copied with some attempt at exactitude. Compare, for example, the pattern on the face of the middle Cherokee with that on the face of Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow. Also note the use of the feather puffs at the ears. The Cherokee at the right bears the facial tattooing of Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row, albeit reversed, and possibly also his earring. The Indian at the left is holding out a belt of wampum, even as King Hendrick does in his Verelst portrait.

143. Major Robert Rogers, 1776

144. The Three Cherokees, 1762

From the Cunne Shote portrait come the gorgets bearing the initials of George III, the silver armband and bracelets, and the frilled cuffs of the hunting shirts’ sleeves. The decorated bands descending from shoulders to waists also might have come from the Cunne Shote portrait.

Possibly I have strained too hard to make a point on the use of the Cunne Shote portrait, but there would hardly have been any reason for the printmaker to use the images of the Four Kings if he had ever seen the Cherokees or even had an accurate description of them.

Rather, it seems to me that the engraver of prints in this period, unless he had a good oil portrait to copy, seldom did anything very imaginative or original. I think his reaction might have been almost like that of a Madison Avenue advertising agency’s art director faced with getting a likeness of an Indian into an illustration and saying:

“Let’s look in the files and see what we’ve got on Indians.”

I would like to express my gratitude to Sinclair Hitchings, Kenneth Newman, Thomas R. Adams, and Miss Jeannette Black for their help and encouragement in the development of this paper. Mr. Hitchings was the one who urged me to pursue the subject and kept supplying me with material and all sorts of assistance. Mr. Newman made all the resources of the Old Print Shop available to me and was most generous in supplying photographs. To Miss Black I am indebted for help on the original work which opened this subject to me: Revere’s portrait of King Philip. Mr. Adams placed the entire resources of the John Carter Brown Library at my disposal; those resources are considerable and fortunate is the scholar who can make this library the focal center of his operation.

Since I delivered the paper, Mrs. Carl Dolmetsch has provided me with photographs of the Schenck mezzotint portraits, now at Colonial Williamsburg, and has informed me that the print of the Three Cherokees who went to London in 1762 is in the collection there.