Boston by Bostonians: The Printed Plans and Views of the Colonial City by its Artists, Cartographers, Engravers, and Publishers

THE Boston News-Letter for May 14, 1722, contained the following advertisement: “MAP OF BOSTON.—A Curious Ingraven Map of the Town of Boston, with all the streets, Lanes, Alleys, Wharffs & Houses, the Like never done before, Drawn by Capt. John Bonner: and Sold by him at his House in Common Street, and also by Messieurs Bartholomew Green in Newbury Street, Samuel Gerrish & Daniel Henchman at their Shops in Cornhill, Boston.”1

This brief announcement introduced to the Boston scene a plan of the town that was to have an extraordinary life. For nearly half a century this engraving was issued, modified, republished, added to, rebordered, extended, newly titled, dedicated, embellished, erased, and festooned along three borders with garlands of lettering in half a dozen different hands.

Nine states of the plan have been identified.2 Its appearance in 1769—the final year of issue—may suggest that it was withdrawn from further publication simply because no more room remained on the plate for additional advertisements, legends, historical and statistical information, lists of fires and plagues, ward names, and other information, the lines and columns of which threatened the shoreline like an invading army.

The original engraving of 1722 was simple, well composed, uncluttered, and attractive. It was the work of Francis Dewing who arrived in Boston from London in 1716. A year later he engraved the first map to be printed in this country from a copper plate.3 His signature outside the lower neat line indicates that he was the printer as well as the engraver. The cartographer’s name, John Bonner, is the only other to appear on this state. It is rather curiously off center in the otherwise symmetrical title.

In the lower left corner is the scale, a list and lettered key to the city’s churches and other important buildings, and the dates of fires and small pox epidemics. On the only known impression of this first state—that in the Stokes Collection—scale and legend are in manuscript.4

Although there are references to an earlier plan of the city, this is the first printed plan of Boston to survive as well as the earliest extant town plan to be published within the present boundaries of the United States.5 For an initial venture it was surprisingly large, measuring just over 16 by 23 inches. The scale is about 500 feet to an inch, and the distance from the tip of North End at the right to the town gate at Boston Neck on the south approaches two miles.

In style, Bonner’s depiction combined a true plan with a perspective. This plan-view technique was popular in Europe, being used for a majority of the plates in the first general atlas of town plans, Braun and Hogenberg’s Civitatis Orbis Terrarum, the initial volume of which appeared in 1572. Blaeu in Holland and Speed in England were among cartographers of the seventeenth century who consistently employed this device.

Bonner’s technique, however, differed from most of these European plan-views in showing the facades of buildings on both sides of every street. He simply drew the houses, shops, churches, and other structures as though they had toppled over backwards. This was a more primitive style out of which developed the more elegant and decorative combination plans and perspectives of European map-makers.

Contrasting sharply with the wealth of crisp details showing manmade Boston are the fragmentary representations of the city’s topography. Beacon Hill appears as little more than a modest rise in elevation—a small mound at one end of the common where the General Court in March 1635 ordered the erection of “a beacon . . . to give notice to the country of any danger.”6

Beacon Hill in fact was but the highest point of a massive and steep triple-peaked ridge running east to west and known as the Trimountain or Tramount. Its top was nearly 140 feet above sea level, some 35 feet higher than the topmost portion today and much more extensive in area. The frontispiece map of Winsor’s Memorial History of Boston shows this ridge, several lower hills in the common on its southern slope, and other small peaks on its northern flank. Two other prominent elevations rose along the eastern edge of the peninsula. To the north of Town Cove lay Windmill or Snow Hill—later Copp’s Hill—while to the south Fort Hill sloped upward even more abruptly from the water’s edge. Copp’s Hill was 50 feet high, and Fort Hill, of which there is now no trace, towered 80 feet above the water.7 In the nineteenth century these hills supplied the material with which Boston’s numerous coves and flats were filled as the shoreline was pushed outwards from the line shown on Bonner’s plan.

Captain John Bonner was a mariner; if he had a good eye for the landscape his draftsmanship managed to conceal it. His depiction of Fort Hill scarcely conveys the impression of what William Wood in 1634 described as “a great broad hill.”8 Nor does Copp’s Hill seem to dominate on paper as it doubtless did on the ground the bustling North End of the city. The windmill may well be the one referred to in Governor Winthrop’s journal as that “brought downe to Boston” in 1632 “because (where it stoode . . . ) it would not grind but with a westerly winde.”9

Churches and other major buildings came easier to Bonner than hills and valleys. Even so, he was no master of architectural detailing. Old North Church in Clarks Square (later North Square) may have been a stern religious sanctuary under the Mathers, but it was hardly the forbidding fortress that Bonner depicts.

Buildings in the very heart of the city do not fare much better. The Old State House at King and Cornhill (now State and Washington Streets) and the various churches in the vicinity seem rather graceless as drawn by the heavy hand of Captain Bonner. Nonetheless, this is an accurate and useful representation of conditions along the principal thoroughfare leading from the Neck, past the new buildings lining Cornhill constructed after the fire eleven years earlier, into Dock Square at the western edge of the Town Dock, and across the artificial ditch of Mill Creek to the North End.

West of this thoroughfare lay the common, reached by a few streets of scattered houses. Eastward, along the shore of South Cove and around Windmill Point to the fort, houses were also irregularly spaced in a much more dispersed pattern of development than in the area north of Milk and School Streets.

Bonner was more at home with ships and wharfs. One-, two-, and three-masted craft appear under sail, at anchor, or moored alongside the Long Wharf, described by Daniel Neal in 1719 as “a noble Pier, 1800 or 2000 Foot long, with a Row of Ware-houses on the North Side, for the Use of Merchants.” Neal added that “the Pier runs so far into the Bay, that Ships of the greatest Burthen may unlade without the Help of Boats or Lighters.”10 The schooner shown at the end of Long Wharf remained, on paper at least, from 1722 through 1725. By 1733, however, in a later issue of the plan, it had vanished—the mysterious victim of an engraver’s whim and hammer.

Sometime prior to April 19, 1725, the plan was reissued.11 Known by a unique impression in the Newberry Library, State ii is little changed from the original, but the additions include the name of William Price who would be responsible for all subsequent editions. This appears at the lower right after Dewing’s name: “Sold by Capt John Bonner and Willm Price against ye Town Houfe, where may be had all Sorts of Prints, Mapps, &c.”

Two sailing craft, a whaleboat, and a canoe make their appearance in the Charles River off the North End. In the title Captain Bonner’s name was embellished with scrolls, a new neat line was drawn inside the first on the left side, and the fortification at Boston Neck was erased and reengraved.

The legend and scale were also engraved, and vertical rules were added to separate the four columns. The population of “near 15000 people” which appeared in manuscript on the first state has now been revised on the engraving to a more realistic “Near 12000 People.”

In the body of the plan Davis Lane appears as an extension of Beacon Street, three previously unnamed lanes are identified, and a horizontal hatching has been added outside the shoreline to emphasize the distinction between land and water.12 State iii, issued later in 1725 or very early in 1726, differs only by the addition under the name of Captain Bonner of the words “Aetatis Suae 80” to call attention to John Bonner’s status as an octogenarian.13

Bonner’s death in the winter of 1725–26 apparently left William Price in sole possession of the plate. Price for some years had been selling cartographic items, advertising as early as 1721 in the Boston Gazette that he had “Prints & Maps lately brought from London.” In 1725 his Gazette advertisement in April and one in the New England Courant in July listed what surely was Bonner’s as “an exact Plan of the Town.”14

Six years after the Bonner plan was first issued and three years after Price issued his first revision a new and somewhat different plan of Boston made its appearance. Undated, but dedicated to Governor William Burnet who filled the office only in 1728, this was drawn by William Burgis and engraved by Thomas Johnston whose signature at the lower right corner omits the “t” in his name. Burgis apparently was the publisher, although Thomas Selby, the proprietor of the Crown Coffee House, the place of sale advertised beneath the lower border, may have been associated with Burgis in this venture.

Burgis, like Dewing before him, had learned his trade in England and had come to Boston at least as early as 1722. His plan of the city was executed with more professional skill than Bonner’s although in style it was more conventional. He indicated built-up street frontages by hatching, while only the churches, major public buildings, and windmills appear in perspective. It was also less ambitious in size, being about half that of the Bonner plan: 10¼ by 14¼ inches.

Burgis obviously copied most of the details of Bonner’s earlier work, plagiarism being traditional among cartographers then as now. Even the letters used in the legend to designate the churches were the same, the only difference being the addition of Christ Church, built in 1723.

The new plan showed topography with somewhat more conviction than its older rival—one gets a sense that the hills had slopes as well as tops, for example—but the Beacon Hill elevation still appears as a single and completely isolated peak rather than merely the highest point of a steep and irregular ridge.

Burgis also showed a line of trees along the mall forming the eastern boundary of the common, a pond on the common, and a somewhat different representation of the gardens west of Beacon Hill identified as “Banisters Gardens.”

A more important detail is the division of the town into eight wards which Burgis showed by dotted lines. He identified this symbol with a notation below the north point at the bottom center.

The large and decorative title and dedicatory cartouche occupying the lower left-hand portion of the plate was a particularly handsome feature of the drawing which Johnston executed with great skill. The contrast between this and the utilitarian simplicity of Bonner’s title could hardly be greater.

7. Detail from the Burgis map: Old South Church (C), First Church (A), Town House (a), Brattle Street Church (F), King Street, Dock Square, and Long Wharf

8. Detail from the Burgis map: Powder House, Watch House, Beacon Hill, Writing School (d), King’s Chapel (E), South Grammar School (c), and Old South Church (C) as previously noted

With the elegance of its Roman, Gothic, and cursive lettering and its graceful delineation of Boston’s complex street pattern the Burgis plan ranks as one of the most attractive examples of urban cartography ever produced in America. Strangely, it is known in only one state, indicating that it was not a commercial success. There is always the possibility that the plate was lost or damaged, but insufficient demand would appear a more likely reason for its early disappearance from the market. Perhaps its qualities of extravagant embellishment and almost playful decoration did not appeal to unsophisticated colonials.

Its publication, however, may have caused William Price some concern. Sometime between 1725 and 1732 Price changed substantially the already altered engraving of John Bonner’s plan. He added a completely new title, historical text, dedicatory cartouche, and advertisement in the upper left-hand corner.

The date 1733 in the title is partly in manuscript, only the numbers one and seven being engraved. Further, in the text below, the figure 3 in the sentence “This Town hath been Settled 103 Years” has been made by adding a curl to what was formerly an engraved figure 2. The 173 3 version is, therefore, State v although no impression of State iv with a date of 1732 has been located.

In the cartouche Price’s name appears beneath the dedication to Governor Belcher who received his commission at the beginning of the winter of 1729–30. This version of the plan thus could not have been published before 1730. Beneath Price’s name are traces of an erased engraver’s signature believed to be that of T. Johnston.15

Bonner’s name was eliminated, and those of Francis Dewing and William Price as they once appeared below the lower neat line were obliterated in part by a heavy border line extending around the four sides of the plan. Of the eight original ships in the lower right-hand corner, three remain and five have been erased only to be replaced by four others.

The legend indicates that the company, or ward, boundaries can now be found on the plan, a feature obviously copied from the Burgis plan. Three churches constructed since 1722 are identified.

A long advertisement below the cartouche informs the reader that Price sold not only views, maps, and prints, but picture frames, looking-glasses, tea tables, China ware, and English and Dutch toys. The only visual virtue of this bit of blatant commercialism is that it distracts one’s eye from the crudely drawn cartouche with its stiffly modeled figures.

Far more distressing, however, was Price’s decision to show new development by hatching the frontage along streets instead of following Bonner’s convention of semistylized but individually depicted structures. The result is not only visually unpleasant and inconsistent but the precision of Bonner’s depiction of the city’s building pattern has now been lost.

The plan, now something of an artistic disaster, is nonetheless a historic record of considerable importance in tracing Boston’s growth. Between 1725 and 1733 many new streets had been laid out in the Neck and leading down to South Cove.

Much in-filling had taken place as well in the area between Milk and School Streets and Windmill Point. The Town Granary, built in 1729, appears near the northeast corner of the common which, as on the Burgis plan, now has a single row of trees on the east.

In the North End, too, some further growth had taken place as houses and other buildings were erected on the slopes of Copp’s Hill between Lynn Street and the Mill Pond.

The area of Boston in which the greatest growth had taken place, however, was the West End, lying between the Mill Pond and Barton’s point on the north and the common on the south. At the western end of Cambridge Street one can see a regular grid of new streets dividing former pasture into blocks and lots. On the other side of Cambridge Street other vacant parcels were also subdivided by new streets to accommodate a population of what the engraving claimed to be 18,000—one-third more than in 1725.

On this new version of the Bonner plan Price continued to make changes, issuing known impressions dated 1739, 1743, 1760, and, finally, 1769. There may very well have been other dates of issue. State vi, a copy of which is in the British Museum, bears the date 1739. The last two digits are in manuscript, and Price could have sold copies in the intervening years with other dates. It would be tedious to trace all the changes in all known states, but those of 1743 and 1769 can be selected as representative examples.

All four digits in the 1743 state are engraved. With characteristic carelessness Price failed to change the number 103 in the text stating the town’s age. He did, however, increase the number of inhabitants for the growing city to 20,000.

Price added to his already overly long advertisement the information that he also sold various kinds of musical instruments, eye glasses, and telescopes. Below, the plate gives the names of what had now become twelve wards, a feature that first appeared on State vi of 1739. That issue also added a second row of trees to the mall on the common.

The legend identified new major buildings, the most recent being Faneuil Hall. This was named for its donor, Peter Faneuil, who in 1742 provided funds for the construction of a market building that also housed on its upper floors the town offices and a meeting hall.

Price, an unknown artist, or his engraver crudely added this and other recently constructed buildings to the plan in a manner completely out of scale with those drawn by Bonner. The only street addition of any consequence is Pleasant Street, leading off Orange Street at the Neck and following the edge of Roxbury Flats northward. Hollis Street now appears extended to cross Pleasant Street and end at the Flats.

Price faithfully recorded still further additions to the street network on the final issue of 1769. Temple and Middlecot Streets now extend south from Cambridge Street to parallel an earlier thoroughfare leading from Beacon Street across the western slopes of Beacon Hill.

The publisher could not resist squeezing additional information about the city in the few remaining uncovered portions of the plate. To the end of the description was added the sentence that “Boston was first Settled in ye Year 1630.” Above, in the text, the age of the town was finally corrected from 103 to 139. The zero was not even erased, but converted to a three by the addition of the upper part of that number.

At the bottom Price felt compelled to list the fires of 1759 and 1760 although no space remained in the proper column. Finally, he added the information below the legend entry for Faneuil Hall Market that market days were Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays.

The metamorphosis of Captain John Bonner’s original plan was at an end. Price died on May 17, 1771, at the age of eighty-seven. His heirs and business successors apparently had no interest in further editions, and Boston was to be without a locally printed detailed city plan for nearly thirty years until the publication of Osgood Carleton’s survey of 1797.16

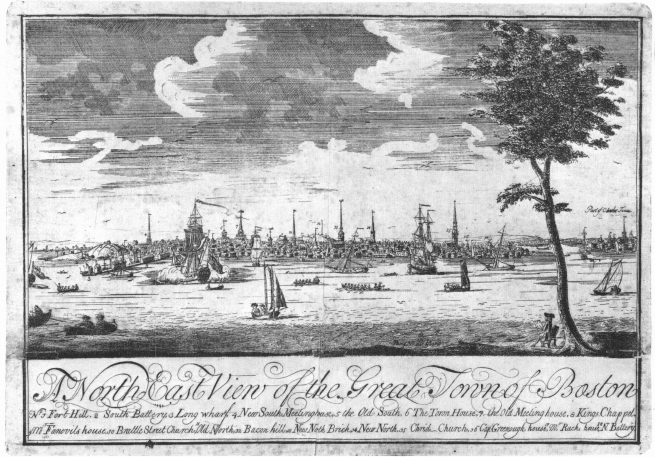

The publication history of the printed views of colonial Boston is equally fascinating. Possibly the earliest, although the date remains a matter of conjecture, is a line engraving entitled “A North East View of the Great Town of Boston” with eighteen numbered references. While undated and unsigned, it is attributed to William Burgis and may have been issued as early as 1723.

The only known copy is in the Essex Institute. It measures 9 ¾ by 12 ¾ inches. Christ Church is shown, so the view cannot be earlier than 1723.

Beneath the tree near the right border is an artist. This may be Burgis as drawn by himself, for on November 12, 1722, Burgis advertised in the New-England Courant that those interested in a view of the town from the northeast should hasten to subscribe so that the drawing might be sent to England for engraving. A month earlier Price had inserted a similar announcement, and Price and Thomas Selby in May 1723 jointly advertised subscriptions for the proposed view still a third time, a notice concluding with the statement that “unless subscriptions come in it will not be printed.”

14. A North East View of the Great Town of Boston, possibly 1723

A fourth advertisement by Price in December 1723 invited subscriptions to a different view from the southeast, implying that the proposed northeast view had never been printed.17 The Essex Institute view is evidence to the contrary, but when, where, and by whom it was engraved may never be known.

The view shows the portion of the city from Fort Hill to the North End. The fort and Long Wharf are the most prominent features at the left.

The central portion reveals the impressive skyline of Boston punctuated by church spires. Far in the distance one can see the beacon atop the peak of Beacon Hill.

At the right is the North End, the mouth of the Charles River, and, to the north at the edge of the view, a portion of Charlestown. If this view was printed in 1723 and was drawn by Burgis, why was Charlestown included here but not on the much larger view of Boston from the southeast advertised for subscription at the end of 1723, offered for sale by William Price in the spring of 1725, and signed by William Burgis?18

The only known unaltered impression of the first state of the larger view is in the Stokes Collection. Engraved on three plates by John Harris, it measures 24 ½ by 52 ½ inches. The dedication contained in a small cartouche at the bottom center is to Samual Shute, governor from 1716 to 1723. The year 1723 is also the last mentioned in the long descriptive passage at the bottom of the left and right sheets.19

In the dedication the name of Thomas Selby precedes that of Price, but the partly obliterated imprint below the text and references reads: “Printed Coulred & Sold by Wm. Price Print & Mapseller over against the Town house in Boston where may be had the Plan of the Town & great Variety of other prints & Mapps & Choice Lookinglasses & all sorts of Pictures framd.”20 Price was not one to let slip by an opportunity for advertising his full line of merchandise.

Fifty numbered references occupy the bottom of the center sheet below the title. The Burgis signature at the bottom left is worn away on the Stokes copy, but there can be no doubt that it appeared there originally as it does on the later state.

The Stokes copy is stained and discolored and separated into four parts, each mounted on a wooden panel. These separations do not correspond with the division of the view into three sheets, so that in its present condition it appears to have six vertical join lines.

At the left one can see all of the Neck with its low and scattered buildings. The fabric of the city becomes more tightly woven to the north of this area and in the vicinity of Fort Hill. Fort Hill itself rises impressively from the water and marks the southern end of Town Cove.

The center panel reveals the truly urban character of this colonial capital. The three peaks in the background which were once such prominent landmarks are echoed by the vertical lines of the numerous spires in the central portion of the city.

On the right stretches the North End with its own churches, wharfs, docks, and boatyards. The mouth of the Charles River is at the extreme right, and no buildings of Charlestown appear.

The British Museum has another impression of this state of the plate to which have been added “pasters” or engraved additions or corrections to the body of the view. These bring the copy up to the year 1736.21 Reference numbers 51, 52, and 53 have been pasted on the legend, and in the body of the view corresponding engraved pasters added the Hollis Street Meeting House of 1731 on the Neck, and the spires of Trinity Church (1734) and Lynds Street Meeting House (1736).

17. The “pasters” which altered the sky line

In 1743 Price reissued the view with numerous revisions, advertising it in the September 22 issue of the Boston News-Letter as “a New Prospect of Boston, neatly done, with the Addition of the Buildings, Churches, etc. to the present year.”22 Among the additions are churches in Roxbury at the far left, Brookline on the distant skyline beyond the land end of Long Wharf, Cambridge above the tip of the North End, and Charlestown at the extreme right.

The dedication, now bearing only Price’s name, has been changed to honor Peter Faneuil, doubtless because of his generous gift to the city for the new market building.

Among the additional references is number 56 identifying Faneuil Hall. The original carefully composed and balanced text was thus altered from the neat columns to accommodate this new material which spills across the join line between two of the sheets.

Price also added an extensive advertisement within an oval enclosure near the bottom of the left side. What must have been a virtual catalogue of his wares was fitted into one of the few spots of open water in the original Burgis drawing.

The spire of the first Faneuil Hall can be seen just to the right of the distant Brookline church. This appears along with other new features of the Boston skyline.

The right-hand sheet was also altered to include the buildings of Harvard College, a detailed view of which Burgis had drawn in 1726 and which Price and other print dealers and bookshops had offered for sale at that time.23 This state of the view still includes the name of John Harris at the lower right, but it seems likely that the many changes in the plate were made in Boston, perhaps by Thomas Johnston, one of the few engravers in the city with the skill to accomplish this painstaking task.

The revisions to the Burgis view of 1743 might, however, have been the work of James Turner. His name appears on two small views of the city similar in scope and also showing Faneuil Hall. They appeared in the same month that Price first advertised the revised Burgis view. One, a type-metal cut, served as the headpiece of The American Magazine and Historical Chronicle which began publication in September 1743. It shows the city from the North End to Fort Hill, the latter feature being partly obscured by what appears to be a palm tree.

19. View of Boston by Turner, 1743

20. View of Boston and scenes of Indians hunting, by Turner, 1743

21. View of Boston by Turner, vignette from map of Halifax, c. 1750

The other is a copper engraving used as the title-page view of the same magazine. The delineation is finer in detail and extends as far south as the Neck, but it appears to have been derived from the same source. Turner used an almost identical view as an inset on his “Chart of the Coasts of Nova-Scotia and Parts Adjacent,” first published about 1750 and re-issued in 1759, 1760, and 1776. In this version measuring 1 ½ by 3 ⅛ inches he omitted the ships in the harbor and added a windmill at the Neck south of the city gate.

Until 1770 no other views of the city were produced by Boston engravers or publishers. In that year, however, two of the three views of the city engraved by Paul Revere made their appearance.

22. Revere’s Prospective View, published in 1770

The earliest was a type-metal cut 3 ⅜ by 6 inches used as the frontispiece for the North-American Almanack for 1770 published on February 22 by Benjamin Edes and John Gill.24 It depicts the city on October 1, 1768, when troops were landed to bolster English authority in the rebellious city. Its strong resemblance to Turner’s copper engraving of almost thirty years earlier is apparent.

Much more elaborate and apparently issued only with hand coloring added is the 9¾ by 15½ inch copper engraving which Revere advertised in the Boston Gazette on April 16, 1770, not quite six weeks after the Boston Massacre.25 Revere undoubtedly engraved the view of “The Landing of the Troops” from a drawing by Christian Remick who apparently colored the prints for Revere, adding his signature to at least one copy.

The wharfs, churches, and major public buildings of Boston appear in some detail. Other structures, however, are presented in a stylized manner, and it would be difficult to identify individual dwellings, warehouses, or places of business.

In the North End the elaborate spire of Christ Church dominates the skyline, flanked by those of Old North on the left and the New North Meeting House on the right.

At the foot of Long Wharf one can see the troops disembarking where, according to Revere’s inscription at the bottom of the view, they “Formed and Marched with insolent Parade, Drums beating, Fifes playing, and Colours flying, up King Street.”

Revere’s third view of Boston is not signed, but there can be little doubt that it was he who executed the engraving in the Royal American Magazine for January 1774. It was featured as the frontispiece view of the first issue of this important illustrated magazine whose fifteen issues were to include twelve other plates signed by Revere.26

While only 6 9/16 by 10⅜ inches, it manages to show much detail. The larger view of “The Landing of the Troops” showed nothing of the city south of Long Wharf, but this, like the earlier Almanack view, includes Fort Hill and portions of Boston toward the Neck.

25. Plan of Boston in 1775

It is curiously distorted in that Fort Hill and the prominent buildings behind it are located much closer to Long Wharf than they really were. Indeed, the entire view appears to be artificially compressed from north to south, doubtless to fit on a relatively small sheet.

The Revolution put an end to Boston’s cartographic and topographic publications. For printed depictions of the city during the period of the war we must turn to plans published in the other colonies and, particularly to England. There were two plans, however, that deserve mention because of their Boston connections.

One shows the city in 1775 with an inset map of Boston and vicinity. It was published in Bickerstaffs New-England Almanack for the Year of Our Lord, 1776. It was printed on the reverse of the title page facing a half page of lettered references to the points of interest identified on the plan.27

Although small in size and rather crudely drawn, it does include one feature which previous and larger plans had largely ignored. This is the representation of the multipeaked ridge beginning with Beacon Hill—identified by the letter “R”—and extending to the west along the northern boundary of Boston Common.

It also shows the location, identified with the letter “K,” of the Liberty Tree near Essex and Newbury (now Washington) Streets. During the demonstrations against the Stamp Act in 1765 effigies of English officials were hung from its branches, its trunk displayed posters denouncing the new tax measure, and around its base mobs of Bostonians gathered to demonstrate their opposition to taxation without representation.28 Cut down by Tories in 1775, this symbol of Boston’s spirit of independence probably no longer existed by the time the almanac plan appeared in print.29

Finally, we come to one of the finest maps of Boston and vicinity ever produced—Henry Pelham’s large and beautiful aquatint engraving. It was drawn by Pelham in 1775 and 1776, engraved on two sheets by Francis Jukes, the two joined measuring 28½ by 42½ inches, and published on June 2, 1777, in London not quite three months after the young artist’s twenty-eighth birthday.30

A Loyalist, Pelham was given access to English military maps and sketches. Among his letters is one in 1775 informing him that “Mr. Robertson the Engeneer . . . Consents to show you his draughts of ours and the enemys Works.”31

26. Henry Pelham’s A Plan of Boston, London, 1777

27. Detail from the center of the Pelham map

At the upper left corner of his map Pelham reproduced a copy of the pass issued to him on August 28, 1775, slightly more than two months after the Battle of Breed’s Hill. This authorized him to visit the front lines for the purpose of completing his map. Ten days earlier he had written to his half brother in London, the artist John Singleton Copley, that a separate map of Charlestown and vicinity was “almost this moment finished.”32

While the Charlestown map was never issued as a separate sheet, the information was incorporated in Pelham’s larger map of the entire Boston area. The Charlestown portion shows clearly the fort on Bunker’s Hill and the smaller fortification on Breed’s Hill to the south which the Revolutionary forces abandoned for lack of gunpowder after repelling two costly assaults by English troops.

Pelham dedicated his map to Lord George Sackville Germain, the secretary of state for the Colonies. It was his confusing orders to English commanders in America and his diversion of troops to the West Indies after the French entry into the war that hastened his country’s defeat. On the Library of Congress copy, Pelham’s manuscript signature was added below the engraved dedication.33

Pelham’s map serves as a vivid reminder of the horrors and hardships that war brought to Boston. Loyalists and English troops, surrounded by Revolutionary forces during the Siege of Boston, occupied only the peninsula and a small additional area beyond the narrowest part of the Neck.

Pelham, writing again to Copley in January 1776, informed his half brother that his next communication would probably contain his “plan of Boston and Charlestown . . . with the Country for three or four miles round this town.” Then, describing the terrible changes in the landscape brought by the war, Pelham reported that there was “not a Hillock 6 feet High but What is entrench’d, not a pass where a man could go but what is defended by Cannon; fences pulled down, houses removed, Woods grubed up, Fields cut into trenches and molded into Ramparts.”

Boston itself had been ravaged:

An hundred places you might be brought to and you not know where you were. I doubt if you would know the town at all. Charlestown I am sure you would not. There not a Tree, not an house, not even so much as a stick of wood as large as your hand remains. The very Hills seem to have altered ther form. In Boston almost all the fences; a great Number of Wooden House, perhaps 150, have been pull’d down to serve for fewel. . . . Dr. Byles’, Dr. Cooper’s, Dr. Ma[t]hew’s Meeting Houses turned into Barracks. Dr. Sewalls’ into a Riding School, Fanuel Hall into a Theatre. The old North pulled down and burnt. Every rising fortified. in short nothing but an actual sight of the town can give an Idea of its situation.34

Boston had come to an end of one era and was about to enter another. New cartographers and topographic artists would record the recovery and growth of the city during the period of mercantile expansion that lay ahead. In a few decades the technique of lithography would largely displace that of engraving and would in turn itself almost vanish with the advent of photography. Boston would be a favorite subject for city views, maps, and plans, but none would surpass in interest those supplied to their clients and customers by the city’s colonial cartographers, artists, engravers, publishers, and print-sellers.