Thomas Johnston

FOR more than a century, historians of the decorative arts in America have gratefully noted down Thomas Johnston (1708–67) as a colonial craftsman who left records behind him. He left them in so many different places, in fact, that no one has caught up with the supply of facts for very long. We have had glimpses of a man of remarkably varied interests and talents, and today we have the makings of a portrait in detail.

Boston house painter and decorator, japanner, engraver, painter of coats of arms, church singer, publisher of singing-books and pioneer New England builder of organs, Johnston was also father of a large brood of children who inherited his skills, added to them, on occasion, and carried them far beyond the boundaries of Boston.

Because Johnston’s career is known in far greater detail than the careers of many of his fellow craftsmen, his name is often pressed into service to try to explain certain examples of colonial handiwork.

His skills as a decorator of furniture have yet to be shown in well-documented examples, but his detailed trade card of 1732 makes him a tempting candidate for authorship whenever scholars study the elaborate applied decorations on a japanned Boston highboy or high chest of drawers.1 The list of his published engravings has grown from eleven in Stauffer and Fielding’s American Engravers on Copper and Steel to roughly three times that number today; he engraved maps, views, trade cards, bookplates, certificates, currency, and book illustrations. One signed watercolor coat of arms by him, of about 1740, exists, others have been attributed to him,2 and there are a number of contemporary references to his heraldic painting. Historians of American music continue to dig out of church records and eighteenth-century books new and detailed information on his singing, engraving of music, songbook-publishing, and repair and construction of organs.

Johnston is a tempting target, as well, for the scholars who in recent decades have unremittingly laid siege to the subject of portrait painting in colonial New England. His dexterity with the brush, in decorating furniture and painting escutcheons, is coupled with other circumstantial evidence and with a variety of attributions by those who envision him as a self-taught, occasional painter of portraits, a generation older than John Singleton Copley and Johnston’s own portrait-painting sons, William and John Johnston.

Most recently, it has become possible to see his decorating business in much greater detail. Nina Fletcher Little has called his successors, Rea and Johnston, “ornamental painters to the elite of Boston,” and in this profitable role they retained the customers and carried on the diversity of business of Thomas Johnston. Johnston would see to the painting of your garden fence or sitting room, sell you gilt paper for a screen, color and varnish your wall maps, sell you a frame for a picture, paint a bedstead for you, stain and varnish a table, provide a stand for your clock or a “desk” for your spinet; he would paint you a coat of arms and have it framed, glazed, and delivered to your house; he would provide funeral decorations, on behalf of your family, if you had suddenly departed this life leaving the means for an expensive farewell.

His penchant for productivity included his role as a father. His sons worked in his shop and learned his skills. Two became japanners and two others portrait painters. One of his daughters married a young painter-decorator, Daniel Rea, Jr., who bought out Johnston’s business at the time of the older man’s death.

His most famous apprentice, John Greenwood, got his start as an engraver and heraldic painter in Johnston’s shop, a first step toward success as a portrait painter in Boston and Surinam, as a mezzotint engraver in Holland, and as an importer and seller of Old Master paintings in London.

History sometimes catches up with a man. Unlike the early generations of the Adams family in New England, as described by Lyman Butterfield, Johnston was not below the threshold of history. Today so much information is available that a book is in order to tell the story in full and print the most revealing of the documents that bear on it. The present article can only suggest the richness of source materials.

Johnston began to be active in Boston about 1726. He stayed close to home and stuck to business for four decades, until his death, at fifty-nine, in 1767.

Nothing is known of his birth, his growing up, or his parents, but two facts are apparent from his first impress on Boston’s historical record: he had schooling from one or more expert craftsmen, and he had capital, either borrowed or inherited. By 1732, when he was twenty-four, he could advertise his own shop with an impressive array of goods and services.

Johnston’s first signed piece of handiwork is William Burgis’ printed map of Boston of 1728, engraved with a skillful display of “copperplate hand” abounding in checks, swashes, and flourishes. Johnston incised his signature into the original copper plate: “Engraven by Thos. Iohnson Boston N. E.”

36. Thomas Hancock Bookseller, 1727

37. Thomas Johnson Japaner, 1732

38. Bought of Samuel Grant, 1736

Thomas Hancock’s trade card, dated 1727, has been plausibly attributed to Johnston by Martha Gandy Fales3 through comparison with Johnston’s own trade card of 1732. In addition to the Hancock card, the Burgis map, and his own card, Johnston’s other dated copperplate engravings are: the fourth state (1732) of the Bonner map of Boston, with extensive additions engraved by Johnston, and his engraved signature; the trade card of Samuel Grant, 1736; manufactory notes issued in different values in the name of James Eveleth, 1741; A Plan of Cape Breton, & Fort Louisbourgh, 1745; Chart of Canada River from ye Island of Anticosty as far up as Quebeck, 1746; John Greenwood’s Prospect of Yale College, 1749; A True Coppy from an Ancient Plan of E. Hutchinson’s, 1753; Plan of Kennebeck & Sagadahock Rivers & Country Adjacent, 1754; engraved psalm tunes with Johnston’s signature and the date 1755; Samuel Blodgett’s A Prospective Plan of the Battle Fought Near Lake George, 1755; Timothy Clement’s Plan of Hudson Rivr from Albany to Fort Edward, 1756; the trade card of Lewis Deblois, 1757; Fortification according to Mr. Blondel, a large folding copperplate page of diagrams issued as frontispiece to The Gentleman’s Compleat Military Dictionary, Eighteenth Edition, Boston, 1759; Quebec, The Capital of New-France, 1759; blank commissions for the Massachusetts province, 1758 to 1767, with the plate being changed yearly; engraved music for Johnston’s own edition of Thomas Walter’s The Grounds and Rules of Musick Explained, 1760; engraved music used in the 1762 edition of Brady and Tate’s A New Version of the Psalms of David; trade card of John Gould Junṛ, c. 1765; South Battery certificate of service (before 1765); engraved music for Johnston’s edition of Daniel Bayley’s A new and compleat introduction to the grounds and rules of musick (Boston, 1766).

39. A Plan of Cape Breton, & Fort Louisbourgh, &c., 1745

41. Prospect of Yale College, 1749

Undated prints by him are: trade card of Andrew Barclay, bookbinder, in two sizes; bookplate of William Smith, a.m.; clock face engraved for Preserved Clapp; bookplate of Samuel Willis; bookplate of Joseph Tyler.

Also among Johnston’s prints (at least in the impressions which were taken from it) is the “anchor and codfish” seal which he designed and engraved for the Plymouth Company in 1753.

42. A True Coppy from an Ancient Plan, 1753

43. Plan of Kennebeck & Sagadahock Rivers, 1754

44. Engraved psalm tunes, 1754

It seems certain that we will identify additional prints by Johnston. John Greenwood recalled that when he was Johnston’s apprentice (about 1742–45), one of his jobs was engraving bookplates.4 None of these plates have so far been identified. Johnston himself may well have engraved trade cards and bookplates other than the few now known, and it also seems likely that he engraved one or more compass cards. One of Daniel Rea, Jr.’s account books shows that within a month after Johnston’s death, the firm was engaged in printing (presumably on Johnston’s copperplate press) compass cards for Jonathan Dupee, instrument maker.5 In the September 1970 issue of Antiques, an article by William H. Guthman on “Surveyors’ Equipment and the Western Frontier” included a reproduction of a compass with an engraved card showing, in the center, a schooner under sail, and around the border the words: “Made & Sold by Joseph Halsy in Fish-Street Boston New Eng.” The instrument is inscribed, on the cover, “Richard Baxter his compass / bought March ye 2d anno 1747.” We know from this evidence that compass cards were being engraved in Boston as early as the 1740’s; only Thomas Johnston and James Turner would probably have had the combination of skill and interest in this sort of engraving to do such a job for a Boston instrument-seller of that decade.6

There are five other “possibles” which may later find a place in the tally of Johnston’s prints.

First, and perhaps the least likely candidate, is a small mezzotint of Increase Mather in the Massachusetts Historical Society. This has under it the legend

Vera

CRESCENTII MATHERI

Effigies

Anno Domini 1683 Aetatis 44

T. Johnson Fecit

This “T. Johnson” might have been the “Thos. Iohnson” of the Burgis map, or he might have been—as Kenneth Murdock argued in The Portraits of Increase Mather in 1924—an English engraver. I think the issue will probably be solved by presenting together, in reproduction, a group of prints, including selected works by the most eligible of the English Johnsons and by Thomas Johnston of Boston, along with Peter Pelham’s mezzotint of Cotton Mather which might, at the end of the 1720’s in Boston, have been the stimulus for another Mather portrait in mezzotint.

A second “possible” is the illustration which seems to have been engraved as frontispiece to William Melmoth’s The Great Importance of a Religious Life (London Printed: Re-printed at Boston for John Phillips, at the Stationers-Arms near the Town-Dock, mdccxxix.). A badly damaged impression is in a copy of this Boston printing of Melmoth’s book, owned by the American Antiquarian Society. It shows “the Crown of Life,” held by angels, at the top, and “Everlasting Burnings” replete with flames and fire-breathing snakes at bottom. Unfortunately it is badly damaged; what survives of the signature reads: “T Iohnso [remainder torn off].”

The other three prints which may be Johnston’s work are known to us through a variety of manuscript and printed evidence.

In May 1755, Johnston charged Thomas Greenough £3.12.0 for “Printing One Quire, Castle Plate.” This sounds like an enlistment certificate, possibly to record service at Castle William in Boston Harbor. Such a print would be the first in a succession which includes Johnston’s South Battery certificate and the North Battery certificate engraved by Revere.

A map of 1762 was credited to Johnston by Stauffer in 1908 on the strength of a notice in the Boston Gazette and Country Journal, June 7, 1762, advertising “A Plan of Part of Lake Champlain, and the Large New Forts at Crown-Point, . . . Done from an Actual Survey by Francis Miller” The print included “References and Explanations of the different Plans,” and, “On the same sheet,” “Perspective Views of Quebec and Montreal.” Though the engraver was not identified, Stauffer undoubtedly was tempted by the way in which the print’s distributors were described: “Sold in Boston by John Draper at his Shop in Cornhill, Thomas Johnston, Engraver, in Brattle Square, Stephen Whiting, Print seller, near the Mill Bridge, Daniel Jones, at the Hat & Helmit, South-End, and by Richard Draper, in Newbury Street.” No impression of the print is known.

In their concise notes on Johnston in Volume III of their edition of Dunlap’s Arts of Design, Bayley and Goodspeed credit him with a Plan of ye Town of Pownal, 1763. Recent efforts to learn more about this print were unsuccessful until just before the present book went to press. Professor W. P. Cumming, listing maps which once belonged to Sir Francis Bernard, governor of Massachusetts-Bay Province, 1760–71, and which now are owned by Dr. J. G. C. Spencer Bernard, Nether Winchendon House, near Aylesbury, Bucks, gives the following title: Plan of ye Town of Pownall by order of ye proprietors of ye Kennebeck Purchase from ye late Colony of New Plymouth . . . Boston 12th Novṛ 1763 Tho Johnston Sculp.

In Boston records, Thomas Johnston is first referred to as “painterstainer”; later, various records repeatedly identify him as “Japanner.” Details of his own definition of these words are found in his trade card of 1732. There he describes his skills as “Japaning Varnishing, Drawing, Gild[ing,] Painting, Eng[rav]ing” (the only surviving copy of the card is slightly damaged; missing letters are here supplied in brackets) and states that

Thomas Johnson Japaner At the Golden Lyon in Ann Street Near the Town-Dock Boston Sells Looking-Glasses Chimney & Peer-Glasses, of all Prizes, Wallnut-Tree, Olive-Wood & Japand, Likewise Japan Work of all Sorts, as Chests of Draws, Chamber & Dressing-Tables, Tea Tables, Writeing-Desks, Book-Cases, Clock-Cases, &c. At the same Place any Gentlemen may be Supply’d with Coach, Chaise, or Sighn Painting at Reasonable Rates.

He had mastered, at the outset, a handsome assortment of ways to earn money. Apparently he prospered, for in 1742 he moved from Ann Street to a house in Brattle Square, described as “Mansion house” twenty-five years later in the inventory of his estate. His shop was a small separate building in the rear. An intimate glimpse of the workings of his business in this setting was given by John Greenwood when in 1749 he was asked to make a deposition for use in a suit over a coat of arms. The contestants, in court, were Johnston and an unhappy customer, Bartholomew Cheever. Greenwood’s comments struck an informal note, perhaps because he was speaking no longer as an apprentice but as a fashionable portrait painter. He declared:

The Deposition of John Greenwood Testifies & Sais ![]() when he was an apprentice to Thomas Johnson At a time when I was at work on some coats of arms, My Master Johnston brough[t] me ye pattern that was produced at ye Inferiour court, and said—“here’s Mr Chevers arms, now you are Upon this sort of work, do one for him, he has Asked me for it a Great many times”—I did one, after it was framed, & Glaized, I carryed it home, gave it to a Young Woman, or a Negro man, they Both came to the Door, I cant tell which took it, I told them Mr Johnston had sent home Mr Chevers’s Arms—I asked if he was at home, but he was not: at least ten Days after, but I believe more, as I was looking out of our workhouse window, I saw a Negro with something square in a Napkin Come up yẹ yard, & go into ye kitchen door,—his master was not with him as he says. I did not remember ye Negro again, neither did I know what he Brought, Untill I went into ye House, were I saw Mr Chevers arms—I Never knew what they came for—but always thought they were sent for some alteration. and further the deponent sais not

when he was an apprentice to Thomas Johnson At a time when I was at work on some coats of arms, My Master Johnston brough[t] me ye pattern that was produced at ye Inferiour court, and said—“here’s Mr Chevers arms, now you are Upon this sort of work, do one for him, he has Asked me for it a Great many times”—I did one, after it was framed, & Glaized, I carryed it home, gave it to a Young Woman, or a Negro man, they Both came to the Door, I cant tell which took it, I told them Mr Johnston had sent home Mr Chevers’s Arms—I asked if he was at home, but he was not: at least ten Days after, but I believe more, as I was looking out of our workhouse window, I saw a Negro with something square in a Napkin Come up yẹ yard, & go into ye kitchen door,—his master was not with him as he says. I did not remember ye Negro again, neither did I know what he Brought, Untill I went into ye House, were I saw Mr Chevers arms—I Never knew what they came for—but always thought they were sent for some alteration. and further the deponent sais not

Boston March the 16.1749 Jn:̊ Greenwood

The contrast between Greenwood’s adventurous career in Boston, Surinam, Holland, and England and Johnston’s application of his talents at home is an intriguing one. Greenwood came from a family with social standing and (on his mother’s side) inherited wealth. He had self-confidence and a desire to try new things, and he had a way of trying them successfully. In one of his early experimental ventures, he almost reversed his earlier relationship with Johnston; it was the former apprentice who drew a view of Yale, and the former master who filled the perhaps secondary or perhaps collaborative role of engraving it in 1749.

Of Johnston’s shop and Greenwood’s experience there, Alan Burroughs has written: “This was not a trade in which there was a promise of wealth. By good management and industry it might have led to a position of public trust and comfortable fortune, as the printing business served Benjamin Franklin. But for the son of an adventurous trader whose every undertaking was a gamble for double or nothing, the career of an engraver of book plates and painter of funeral decorations could not have been advantageous, at least from the point of view of recouping the family fortune.”7

47. Lewis Deblois At the Golden Eagle, 1757

During their time together as master and apprentice, Johnston and Greenwood (as the deposition of 1749 suggests) shared experiences which left a lasting impression on both men. Probably the earliest was the funeral of William Clark in 1742. Clark had lived lavishly; his house in Garden Court Street was one of the sights of Boston. Though he died after heavy financial losses, the family still had means for an elaborate funeral. Johnston was paid £57 for drawing a coat of arms which William Codner cut on stone; included in the sum was the cost of an escutcheon and stockings for the funeral horses. Later, Greenwood recalled that it was he, as Johnston’s apprentice, who made the escutcheon and the arms.8

48. Fortification according to Mr. Blondel, 1759

Johnston’s life and Greenwood’s were interwoven for perhaps less than a decade. A relationship about which we know less, though it seems to have lasted throughout Johnston’s working life, is his acquaintance, perhaps friendship, and sometime business association with William Price.

Price employed Johnston to engrave copious additions to the Bonner map of Boston in 1732. In 1736 he was a subscriber, as was Johnston, to a fund to purchase an organ for Christ Church, Boston. In 1739 he and Johnston were associated in making the inventory of the estate of Robert Davis, japanner.9 On the revised map, as on the list of subscribers of 1736 and the inventory of 1739, their names appear, but these are the only direct evidences of relations between them.

These two men made contributions to music in Boston which were unique in their generation. Price was New England’s first organist, Johnston her first builder of organs. In one way or another—as negotiator of a sale, or as an organist sometimes acting as a volunteer, sometimes with a salary—Price seems to have played the leading role in making a place for organ music in Boston for more than forty years, beginning in 1714 when he was apparently the only person in Boston who could play the organ willed by Thomas Brattle to King’s Chapel.

Johnston, the younger man, appears in church records as a leader of singing at the Brattle Square Church in 1739 and as a singer, probably a soloist, at King’s Chapel in 1754 and 1756. The first evidence of his interest in the construction of organs comes in 1743, when he overhauled the first organ used by Christ Church. This had been purchased by the church from William Claggett of Newport in 1736, after William Price went to Newport, examined the instrument, and recommended it.

Later, Johnston was to build an organ which replaced this one; Christ Church specified in 1752, when he was given the job, that he make the instrument “with the Echo equall to that of Trinity Church of this Town”—Trinity’s organ being an import from England. He also completed, in 1754, an organ for St. Peter’s Church, Salem. Among the effects listed in the lengthy inventory of his estate in 1767 were “part of an Organ” valued at eighty shillings and “an Organ unfinished.”10

Johnston the engraver, Price the print-publisher and printseller; Johnston the japanner who sold such a variety of decorated furniture, and Price, who was in business earlier and sold japanned furniture himself; Price the organist and Johnston who learned how to repair organs and even to build them; there are affinities between these men which might well repay additional research.

Most Boston japanners, wrote Esther Stevens Brazier after study of the Boston probate records, “died insolvent and intestate.” Thomas Johnston, however, made money, kept it, and passed it on (though by means of the briefest of wills, made while he was dying).11 He must sometimes have been seriously short of cash, nevertheless, for in 1759 James Boies, wharfinger, sued him to obtain payment for wood delivered to his home in 1758 and 1759; in 1760 he was sued by Henry Coolege, Cambridge victualler, who listed unpaid bills for beef, pork, cabbage, and tongue going back from 1759 to 1753, and Coolege had to sue again in 1762 to obtain full payment. Johnston was in court on other occasions; so were his sons Benjamin and Thomas, Jr. There seems to have been a streak of the litigious New Englander in the family.

By unrelenting industry and by the diversity of his skills, Johnston continued to add to his sources of income. His map-engraving took an unexpected turn in 1753 when he was visited by Henry Gibbs, Belcher Noyes, and William Skinner. These gentlemen “agreed with me to engrave a Plan of Casco-Bay & Kennebeck-River, with the Lands adjacent.” They brought him various maps and copies of maps, and the plan was quickly engraved by Johnston and issued by the proprietors of the Township of Brunswick with accompanying letterpress. Johnston suddenly found himself in the thick of a controversy between the Brunswick proprietors and the Plymouth Company over the ownership of Maine lands. In Lawrence Wroth’s words,

49. Quebec, The Capital of New-France, 1759

Soon after its publication as part of the Brunswick propaganda, Johnston admitted to the Plymouth Company that the small map had been a somewhat hit-or-miss, composite reproduction made up of earlier separate surveys, and furthermore, that he had omitted or added to it certain features upon orders from members of the Brunswick committee. For these admissions, published as an affidavit in one of the pamphlets in the controversy, he was criticized in both sorrow and anger by the Brunswick people and, quite naturally, taken at once under the protective wing of the Plymouth Company.12

50. Province of Massachusetts-Bay officer’s commission, engraved in 1758

51. Engraved music, 1760

A week before Johnston’s affidavit, dated Boston, February 1, 1753, the Plymouth proprietors had voted to commission him to engrave a seal for their company; later, in 1754, they paid him for making preliminary drawings for a large map of the Kennebeck area. They also paid for the two copper plates on which he engraved it. Great labor went into this map, which measures 31½ by 22 inches, contains a wealth of detail, and has very extensive historical notes engraved in areas not covered by the central map design and an inset.

In Wroth’s words, “Whoever may have lost by this controversy, it was certainly not Johnston, the engraver, who worked for both sides.” The big map became one of Johnston’s staple and salable products. It was influential, too, being reengraved in England in 1755. The inventory of Johnston’s estate in 1767 contains an entry referring to this and two other maps—his Chart of Canada River and his Plan of Cape Breton, & Fort Louisbourgh—which he apparently kept in stock: “12 plans of kennebeck, 8, of Cannida, 6 of Louisburgh.” They were valued at a total of twelve shillings.

While Johnston was engaged in this strenuous, controversial, and profitable adventure, he was at work on another undertaking which was to prove much more profitable.

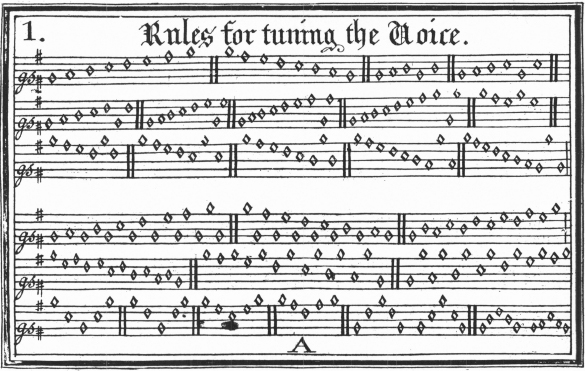

In 1753 he had been a member of the committee appointed by the Brattle Street Church to issue a revision of the Psalms of David. Possibly as part of this enterprise, Johnston engraved sixteen pages of music, beginning with instructions titled “To learn to sing, observe These Rules,” and carrying the imprint “Engrav’d Printed & sold by Thomas Johnston Brattle street Boston 1755.” These pages printed from copper plates could be bound in at the back of any “singing book” which provided the words of hymns printed by letterpress. Apparently they proved to be a gold mine. They are found bound into many Boston editions of Brady and Tate’s A New Version of the Psalms of David, up to 1767, and were also bound into a 1762 edition of Isaac Watts’s Hymns and Spiritual Songs and a 1763 edition of Watts’s The Psalms of David, Imitated in the Language of the New Testament. In Johnston’s will dictated on his deathbed he presumably stuck to essentials. He said, simply: “I Thomas Johnston Give to my Wife Bathsheba Johnston all my psalm Tune plates together with the Press besides what her proportionable part of my Estate may be.”

52. Engraved music, 1762

Johnston may have engraved as many as four sets of the psalm tune plates. The first set, with his imprint of 1755, was apparently put through the press with great frequency; as the plates became worn, he went over them, deepening and strengthening the lines. He also altered the page numbering of the original plates. By 1762 he had a new set of plates, with larger titles and page numbers and more relaxed copperplate lettering. He seems to have continued using the earlier plates, too.

A third set of plates, without his signature but almost certainly his handiwork, was first used in his own edition of Thomas Walter’s The Grounds and Rules of Musick Explained. A copy with the imprint “Boston: Printed by Benjamin Mecom at the New Printing-Office near the Town-House, for Thomas Johnston, in Brattle-Street” may date from 1760; later, the imprint was changed to read “Boston: Printed for, and Sold by Thomas Johnston, in Brattle-Street, over against the Rev. Mr. Cooper’s Meeting-House. 1764.”

53. John Gould junr. at the Crown and Sceptre, c. 1765

54. South Battery certificate of service, before 1765

55. Engraved music, 1766

Still a fourth set of engraved pages of music printed from copper plates appears in Johnston’s edition of Daniel Bayley’s A new and compleat introduction to the grounds and rules of musick (Boston, 1766). The original engraved designs for four of these pages of music still exist on a copper plate preserved at the Essex Institute. On the other side of the plate is a clock face, signed by Johnston and engraved for Preserved Clapp, whose name appears in the design.

In Johnston’s hands, and with his deserved reputation as a man of music, engraving and publishing the psalm tunes had become a thriving branch of his business. A copy of what probably was his own edition of Walter’s book is listed in a bill which is printed here in full because of the picture it gives of Johnston’s matter-of-fact ability to carry on many different kinds of work. (Not the least of his talents, incidentally, was knowing how to charge. The prices in his neatly written bills have a solid look to them.) Here is the bill, transcribed from the original in the Lemuel Shaw Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society:

Mr: Samuel P. Savage to Thomas Johnston Dr

|

1762 |

To Collouring & Varnishing a Table Son |

0.2.– |

|

|

Aug 20 |

To painting a Beadsteed green |

0.8.– |

|

|

do |

To one of Walters Sing Books to Sone Billy |

‘ .3.4 |

|

|

To painting the New fence in yr Garden |

0.12. |

||

|

To painting a pair of Chaise Wheeles |

0.6.0 |

||

|

Sept 1 |

To fixing Roles on to Six large Mapps Collouring and Varnishing ditto 6/ |

1.16.0 |

|

|

Octobr 1 |

To making a Stand for yr Spring Clock to Stand on |

.10. |

|

|

To 2 pounds of whiting to Boston |

6.0.4 |

||

|

Janr 8 |

To painting a Sash white |

0.1.0 |

|

|

May |

To painting yr Silling Room Twice Over |

1.12.– |

|

|

6 |

To a pair of frosts |

0.2.8 |

|

|

1763 |

To Gilt paper for a Screene |

0.3.4 |

|

|

Janr 3 |

To Cash lent your wife by Dilly |

0.6.– |

|

|

To Making a mahogany Desk for a Spinnett |

0.10.0 |

||

|

Febry 13 |

To Sundries pr Mr Drowne Note for yr wifes Coffin |

2.14.1 |

|

|

April 23 |

To Making a handsome Half length Picture |

||

|

Frame inside edge Carvd & Gilt |

2.13.4 |

||

|

£12.0. 5 |

|||

|

368 |

|||

|

15:7:1 |

|||

|

June 26 1764 |

To painting a Chest Son Will |

:3:4 |

|

|

Sep 8 |

To 1 handsome frame yr Picture |

2:13:4 |

|

|

To writing aboard yr Warehouse |

6– |

||

|

To paintg yr Chimney & Iams |

4– |

||

|

3:6:8 |

|||

|

Errors Exceptd: pr Thomas Johnston |

|||

56. Engraved music printed from a surviving Johnston copper plate

The two handsome frames most likely were for the portraits which John Singleton Copley painted of Savage and his first wife. Savage clearly was a good customer of Johnston’s, and he may have been a friend. He was a widower in 1767 when Johnston died, and later that year he married Johnston’s widow Bathsheba. Entries in the Rea & Johnston accounts at the Harvard Business School mention her frequently. She seems to have had the means and freedom to indulge her desires for the upkeep and decoration of her new household; perhaps, after all, this was the style to which her new husband was accustomed.

Johnston left a substantial estate, a healthy business, and a legacy of skills. We know something about the careers of eight of his children:

Thomas Johnston, Jr. (1731–76?) is described in court cases as “Gentleman” and “Japanner.” He served in the French and Indian Wars, being briefly at Fort Edward in the summer of 1757 and taking part in the Canada expedition of 1759.

William Johnston (1732–72), described in an entry of 1760 in the ledger of Daniel Rea, tailor, as “Limner,” painted coats of arms as well as portraits and derived income at times from his ability to play the organ. He served as organist of Christ Church, Boston, from 1750 until his coming of age in 1753; he painted portraits in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, about 1760 and again about 1762, in New London, Connecticut, 1762–63, and in Hartford and New Haven, 1763–64. More than thirty portraits by him are known. He married Christian Bruce of Boston, December 2, 1766, in the Brattle Street Church. By 1770 he was in Barbados, and apparently again single. He continued to paint and obtained the post of organist in St. George’s Parish. Dying in Bridgetown, Barbados, in 1772, he left all of his estate to his “dear and loving friend Rachael Beckles” of Barbados. He was a friend and correspondent of John Singleton Copley; from New Haven in 1764 he had sent Copley a life of Jan Steen, and he wrote Copley a long letter from Barbados in 1770.

57. Andrew Barclay trade card: two sizes on one plate

58. The small Barclay card

59. The large Barclay card

Sarah Johnston (1736–84) married, in 1759, Wensley Hobby of Boston and Middletown, Connecticut. They had five children. Sarah made Middletown a family center for the Johnstons second only to Boston. William Johnston seems to have visited the Hobby’s there, and in his letter of 1770 to Copley he asks Copley (“such is my affection for her”) to paint a miniature of her. Samuel Johnston (1756–94), her half brother, came to live in Middletown after his marriage, as noted below.

Benjamin Johnston (1740–1818), is mentioned in the ledger of Daniel Rea in an entry of 1761 as “Japaner.” A writ of attachment against him in 1763 describes him as “Benjamin Johnston of Salem . . . Painterstainer”; the deputy sheriff who visited Johnston’s home attached “one Silver watch and twelve picters.” In another writ of 1763 he is identified as “Benjamin Johnston of Salem . . . Japanner.” He later moved to Newbury, and there in 1770 he married Anne Stickney; they had six children. His skills are said to have included the building of organs, and they also included drawing and engraving. The earliest surviving view of Newburyport is his handiwork. Titled A North-east View of the Town & harbour of NewburyPort, it is a copperplate engraving which contains the line, at top, “From a drawing by Ben. Johnson 1774.” The key, engraved at the bottom, lists “A The Town House | B. Merimack River | C. Rope Walk | D. Frog Pond | E. Salisbury |.” The frog pond in this primitive view sports a comical cow and three comical ducks. Johnston advertised the print in The Essex Journal and New Hampshire Packet, January 19, 1775.

Rachel Johnston (1746?–1801) married Daniel Rea, Jr., in 1764. They had twelve children. Rea was a painter and decorator, and he was also a singer of some repute. According to a chronicler of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company, “For several years he was a soloist at the anniversary dinners of the company, the entire company joining in the choruses. It is said that at one time by request he sang in the presence of George Washington.” His father-in-law had been a member of the company, too, from 1742 to his death. It was Rea who wrote down Johnston’s brief will when the older man was dying; after Johnston’s death he bought out the business, running it for a time (from 1773 to about 1787) in partnership with young John Johnston, and carrying it on into the early years of the nineteenth century. Rea’s account books, and the account book of Rea & Johnston, are in the Baker Library of the Harvard Business School.

All the children mentioned so far were born to Johnston and his first wife, Rachel, daughter of John Thwing. Three of their children, two boys named Samuel and a girl named Martha, appear to have died early in life. Rachel herself was little more than forty when she died about 1746. Later Johnston married her second cousin, Bathsheba Thwing. They had three children:

James Johnston, about whom little is known, was a mariner in 1772.

John Johnston (1752–1818) was apprenticed, possibly after his father’s death in 1767, to John Gore, house and sign painter and father of Governor Christopher Gore. In 1773 he married Martha Spear; they had six children. He went into partnership with Daniel Rea, Jr., in the painting and decorating business, and in 1775 he entered the army, serving as a lieutenant in Gridley’s artillery regiment and in 1776 as a captain in Knox’s regiment. At the battle of Brooklyn, Long Island, in August 1776, he was badly wounded and taken prisoner. He left the service in October 1777, and resumed his work in Boston. He painted portraits as early as 1781, and by the late 1780’s was working full-time as a portraitist. This was his calling for the rest of his life. More than fifty-five of his portraits are recorded, and there are probably others within easy reach. John Johnston’s paintings have directness and candor about them; as likenesses, they convince. He also painted signs; a still life by him was noted by Frank Bayley, and he painted an altarpiece for Christ Church, Boston.

60. Bookplate of William P. Smith

Samuel Johnston (1756–94) probably worked in the Johnston shop as a boy, for in 1780, in a quitclaim deed to the Brattle Street property once owned by his father, he signed himself as “Samuel Johnston of Boston, painter.” By then he had probably been to sea; later he became a master mariner, “Captain Johnston,” in the West Indies trade. He married Comfort Sage of Middletown, Connecticut, in 1780; they had four children. She died in 1790, and in 1791 he married Hope, the widow of William Warner. From the time of his first marriage his home had been in Middletown. He was lost at sea on a homeward passage from Santo Domingo in 1794.

61. Clock face engraved for Preserved Clapp, printed from a surviving copper plate

62. Bookplate of Joseph Tyler

It may yet be proved that in addition to all his other talents, Thomas Johnston painted portraits. Since there are no signed portraits by him, and the attributions to him in the past have been in terms of speculation or tradition, I personally feel the question is open.13 Though I have not yet been able to discover portraits which are definitely his, I find myself going back to a few pictures by other hands which have a peculiar interest as background to his own life and activities. There is John Singleton Copley’s portrait of 1753 of an engraver, dressed in his best clothes and seated at a table with his burin in his hand, other tools, including another burin, a pair of pliers, a burnisher, a scraper, and a plate-holder on the table beside him, and in the background an anvil and hammer. There are Copley’s portraits of Nathaniel Hurd, painted about 1765, and Paul Revere, painted about 1768–70—Hurd seated with two books, one of which is J. Guillim’s Display of Heraldry, on the table in front of him; Revere also seated, holding a silver teapot in his left hand, resting that hand on an engraver’s sandbag, and with two burins and a needle with a wooden handle in easy reach on the table.14 Finally, in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection at Colonial Williamsburg, there is a painting of 1781, by an unknown artist, of Peter Farrington who is said to have been a Boston organist. Farrington holds an open hymnbook in his hand; he stands in front of one of the small organs of the day. There may be other equally appropriate pictorial documents of some of Johnston’s compatriots; these at least are a beginning.

An Inventory of the Real and personal Estate of Mṛ Thomas Johnston late of Boston Jappanner deceḍ as apprizd: by us ye Subscribers July 1767–

sources

Because of the abundance of sources, an attempt has been made to limit footnotes and to summarize here the major sources as they are presently known.

Manuscripts

In the Massachusetts Historical Society, bill dated March 1746 to Thomas Greenough (most of the charges are for japanning compass boxes); bill of February and March 1747/8 for a hatchment, silk escutcheons, and other expenses of the funeral of the Hon. and Mrs. Anthony Stoddard; bill dated January 26, 1757 to Thomas Greenough for japanning compass boxes and a spy glass and for printing; bill of 1764 to Samuel P. Savage, printed here in full; letter of 1762 from William Johnston in New London to Thomas Johnston; conveyance of June 2, 1768 by which Samuel P. Savage received £33.6.8 and Daniel Rea, his wife Rachel, and James, John, and Samuel Johnston received from him “all and Several the Goods brought into my Family by their Mother my now present wife”; letter of May 4, 1770 from William Johnston in Barbados to John Singleton Copley in Boston.

In the Probate Records, Suffolk County Courthouse, Boston, Johnston’s will of May 7, 1767; inventory of his estate, dated August 7, 1767, printed here in full; appointments of August 21, 1767, making Johnston’s widow Bathsheba the guardian of James, John, and Samuel Johnston.

In the Office of the Clerk of the Superior Court of Suffolk County, Superior Court Records No. 165237 (deposition, 1731, by Thomas Johnson [sic] as to Nathan Thwing); 166051 (deposition by Josiah Flagg, 1734, concerning scuffling apprentices who burst open the alley door of the house of Thomas Johnson [sic] “and broke his Glasses”); 66384 (deposition of John Greenwood, 1749, as to Thomas Johnson [sic] to whom he had been apprenticed, concerning the making of a coat of arms for Bartholomew Cheever), printed here in full; 68755 (writ of execution, 1751, of court decision awarding Bartholomew Cheever of Boston, merchant, £2.0.4 as well as costs of suit against Thomas Johnston of Boston, japanner); 79266 (writ of attachment, 1758, on behalf of James Boies of Boston, wharfinger, to recover from Thomas Johnston, japanner, money owed for wood delivered to Johnston’s home; with the writ is Boies’s bill for deliveries of wood to Johnston in 1757 and 1758); 80734 (writ of attachment, 1760, on behalf of Henry Coolege of Cambridge, victualler, against Thomas Johnston of Boston, japanner, to recover the amount of unpaid bills, 1753–59, for beef, pork, cabbage, and tongue); 82974 (a further suit by Coolege against Johnston in 1762 to recover remainder of sum unpaid after judgment of 1760); 172920 (writ of attachment, 1765, against Abraham Stickney of Tewksbury, yeoman, who had taken fifteen singing books on two months’ consignment from Thomas Johnston and had returned neither books nor payment); 78339 (writ of attachment, March 14, 1758, on behalf of Joseph Gooding, Falmouth, York County, mariner, against Thomas Johnston, Jr., of Boston, japanner, to recover money loaned to Johnston); 78630 (writ of attachment, May 1758, on behalf of Thomas Johnston, Jr., of Boston, gentleman, to recover money owed by Jonas Cutler of Waltham, trader (with the writ is Johnston’s bill to Cutler “to writing for you and attending your stores” at Fort Edward, June 21—July 18, 1757); 78637 (writ of attachment, May 1758, on behalf of Jonas Cutler against Thomas Johnston, Jr.); 83965 (writ of attachment, 1763, on behalf of Philip Freeman, glover, of Boston, against Benjamin Johnston of Salem, japanner, to recover money lent to Johnston); 85099 (writ of attachment, 1763, on behalf of Gibbes Atkins of Boston, cabinetmaker, to recover from Benjamin Johnston of Salem, painterstainer, money lent to Johnston).

In the collections of Baker Library, Harvard Business School, the ledger of Daniel Rea, tailor, for 1750–74, including accounts with Thomas Johnston, and the account books of Daniel Rea, Jr., and Rea & Johnston, containing references to various members of the Johnston family.

In the manuscript records of Christ Church, Boston, bills for repair of the church’s first organ and construction of its second organ (see Babcock’s Christ Church, Salem Street, Boston, where several are printed).

In the manuscript records of King’s Chapel, votes to continue Thomas Johnston as a singer (see Henry Wilder Foote, Annals of King’s Chapel, ii [1896], 103, 172, 186).

In the Public Record Office, London, letter of September 14, 1764 from William Johnston in New Haven to John Singleton Copley in Boston (Public Record Office, C.O./38, fols. 52–53).

In the New London County Historical Society, New London, Connecticut, bill of April 11, 1763, from William Johnston to Nathaniel Shaw, Jr., for painting portraits.

Books and Articles

In addition to sources mentioned in the text and footnotes, the following are particularly helpful: George Francis Dow, The Arts and Crafts in New England, 1704–1773, (Topsfield, Mass., 1927), pp. 8–9, 21, 23–24, 28, 29–31, 298; Cornelia Bartow Williams, Ancestry of Lawrence Williams, Part ii, Ancestry of His Mother, Cornelia Johnston, Descendant of Thomas Johnston of Boston, Mass., 1708–1767, pp. 177–183; Frederick W. Coburn, “The Johnstons of Boston,” Art in America, xxi (December 1932), 27–36, and (October 1933), 132–138; Mabel M. Swan, “The Johnstons and the Reas—Japanners,” Antiques, xliii, No. 5 (May 1943), 211–213; W. H. Whitmore, Notes Concerning Peter Pelham, . . . and His Successors Prior to the Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1867), pp. 25–26; James Clements Wheat and Christian F. Brun, Maps and Charts Published in America before 1800, A Bibliography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1969), items 71, 76, 161, 163, 191, 227–229, 320, and 322; Eliot I. Wirling, “Pipe Organs of New England,” Old-Time New England, xlv, No. 2 (October–December 1954), 38–41; Leonard Ellinwood, The History of American Church Music, revised edition (New York: Da Capo Press, 1970), pp. 55–56; [Thompson R. Harlow,] “William Johnston, Portrait Painter, 1732–1772,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin, 19, No. 4 (October 1954), 97–100, 108; Thompson R. Harlow, Ralph W. Thomas, and Robert C. Vose, Jr., “Some Comments on William Johnston, Painter, 1732–1772,” Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin, 20, No. 1 (January 1955); J. Hall Pleasants, “William Johnston, Portrait Painter 1732–1772,” The Walpole Society Note Book (1955), pp. 27–29. Lila Parrish Lyman’s article on William Johnston, mentioned in footnote 13, contains the best brief summary of birth and death dates of Thomas Johnston, his wives Rachel and Bathsheba, and his children. Johnston’s engraved music is most easily studied in the collection of American songbooks at the American Antiquarian Society, Worcester. For Benjamin Johnston, see John J. Currier’s History of Newburyport, Mass. 1764–1905, 1 (Newburyport, 1906), 79; Johnston’s engraved view of Newburyport is reproduced, p. [80]. Part ii of Coburn’s article, mentioned earlier, is helpful especially for information on John Johnston. For further information on him, see typed page of notes by Frank W. Bayley in John Johnston file, Paintings Department, Boston Museum of Fine Arts; also Louisa Dresser, “The Thwing Likenesses—A Problem in Early American Portraiture,” Old-Time New England (October 1938), pp. 45–51; also American Portraits 1620–1825 Found in Massachusetts, 2 vols. (Boston, Mass.: Works Progress Administration, The Historical Records Survey, May 1939).

Shortly before going to press, another bookplate by Thomas Johnston has been added to our store of illustrations. We reproduce it here, in available space, outside our numbered list of illustrations. It is believed to have been used by Lt. Gov. Andrew Oliver (1706–1774) and is reproduced by courtesy of Andrew Oliver, who reproduced it on the inside front cover of his Faces of a Family, 1960.