APRIL MEETING, 1933

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held, at the invitation of the Reverend Edward C. Moore, at No. 21 Kirkland Street, Cambridge, on Thursday, April 20, 1933, at eight o’clock in the evening, the President, Samuel Eliot Morison, in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

The Corresponding Secretary announced the death of Charles Sedgwick Rackemann, a Resident Member and the last of the founders of the Society, on March 29, 1933; of Waldo Lincoln, a Resident Member, on April 7, 1933; and of Heman Merrick Burr, a Resident Member, on April 14, 1933.

The President appointed the following committees, in anticipation of the Annual Meeting:

To nominate candidates for the several offices, — Messrs. George Pomeroy Anderson, James Phinney Baxter, 3rd, and Robert Ephraim Peabody.

To examine the Treasurer’s accounts, — Messrs. Matt Bushnell Jones, Richard Ammi Cutter, and Henry Lee Shattuck.

Mr. George Frederick Robinson, of Watertown, Mr. Ludlow Griscom, of Cambridge, and Mr. Howard Corning, of Salem, were elected Resident Members of the Society; and Mr. Howard Miller Chapin, of Providence, and Mr. Robert Francis Seybolt, of Urbana, Illinois, were elected Corresponding Members.

Mr. Arthur O. Norton presented by title the following paper:

HARVARD TEXT-BOOKS AND REFERENCE BOOKS OF THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY790

The scantiness of our knowledge concerning the text-books and other books used — or at least owned — by Harvard students of the seventeenth century led me in 1909 to begin a search for further light on this neglected but fundamentally important aspect of the history of Harvard College.

At that time practically all that was known on the subject was contained in the then unpublished Corporation Records for the years 1636 to 1750,791 and in three other documents, all of which had been printed. Those three are (1) the detailed account of the college which appeared in New Englands First Fruits (1643);792 (2) Jonathan Mitchell’s (H. C. 1687) copy of the College Laws of 1655;793 and (3) a single page of MS. in the Harvard College Papers (I, No. 31), headed “A particular Account of the present Stated Exercises Enjoyned the Students.”794 This last was neither dated nor signed by its writer; but someone — probably Mr. T. W. Harris, who arranged the papers for President Quincy in the 1830’s—has pencilled the tentative date “1690?” at the top of the page. For want of evidence to the contrary, I long accepted this date. It was not impossible, since every book mentioned by title in the document was published before 1690. However, on re-study of the records in 1929, I was able to prove that the actual date is not 1690, but 1723, and I shall refer to this paper hereafter as the list of 1723.

This new date brings into the picture a fourth document, which is now, for the first time, proved to be the final and official form of the list of 1723. It was incorporated by President Wadsworth in his diary under the date March 15, 1725/6. I shall call this “particular Account,” as Wadsworth styled it, the list of 1726.795

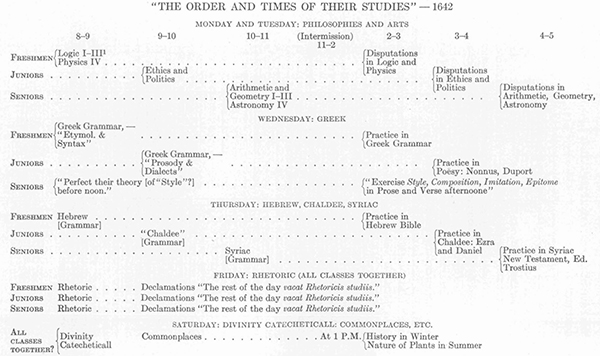

The information given by these four documents may be disposed of briefly. The College Records for this period mention only one text — “the Originall of the old & new Testament.”796 President Dunster’s Bible, now in the Harvard College Library, is doubtless an example. The Old Testament, in his copy, is mainly in Hebrew, but the books of Ezra and Daniel are in “Chaldee,” now identified as Aramaic. The New Testament is in Greek, but the Syriac version of the Gospels is bound in the same volume. These, the original languages of the Word of God, must be mastered by all who sought to understand “the true sense and meaning” of that Word. The requirements for graduation from college throughout the seventeenth century, be it noted, included an examination of the student’s ability to “read [i.e., translate] the originall of the old & new Testament into the Lattin Tongue.”797 The four languages, Hebrew, “Chaldee,” Greek, and Syriac, appear in the earliest existing programme of studies (1642), and there can be no doubt that they were included mainly, if not wholly, to enable the student to read the Word of God in those languages.

The programme of 1642 mentions, in addition to the Bible, only three books. These are rather vaguely indicated as “Nonnus798 and Duport,”799 in connection with the study of Greek poetry, and “TrestiusNew Testament,”800 so placed as to indicate a connection with Syriac.

The College Laws of 1655 name no text-books whatever. The four just named, then, are the only ones indicated by the sources prior to the list of 1723.

The list of 1723, dated eighty-five years after the opening of the college, is the earliest document which gives detailed information as to text-books. It not only records the studies and exercises for each of the four years of the college course, but also names more or less explicitly eighteen text-books, and indicates the use of five others in connection with these studies. It is here reproduced:

A particular Account of the present

Stated Exercises Enjoyned the Students

The first year The Freshmen recite the Classick Authours Learn’t at School viz Tully Virgil Isocrates Homer with the greek Testam[en]t & greek Catechism & Dugards or Farnabys Rhetorick801 & the latter part of the year the Hebrew Grammar & Psalter Ramus’s & Burgesdicius’s Logicks

The Second year The Sophimores recite Bu[r]gesdicius’s Logick and a Manuscript called the New Logick Extracted from Legrand and ars Cogitandi802 Wollebius on Saturdays and in the Latter part of the year Herebords Meletemata continuing stil most part of the year recitations in the formentioned greek & Hebrew books and dispute on Logical Questions twice a week

The third year The Junior Sophisters recite Herebords Melletemata Mr Mortons Physicks Dr Mores Ethicks a system of Geography & a System of Metaphysicks Wollebius’s Divinity on Saturdays & dispute twice a week on Physical & Metaphisical & Ethical Questions

The fourth year The Senior Sophisters recite Alsteds Geometry Gassendus’s astronomy goe over the arts viz Grammar Logick & Natural Phylosophy Ames Medulla & dispute once a week on phylosophical & astronomical questions803

As noted above, I long accepted the incorrect date 1690 for this list, and assumed that the text-books therein named were actually in use in the college at that time.804 I therefore began an attack on the unknown period between 1642 and 1690, for which the only documents were the Order of Studies of 1642 and the College Laws of 1655.

Although they name only four text-books, these two combine to furnish a clear account of the studies and exercises in vogue during the early years of the college. The programme of 1642 is remarkable for its detailed schedule of studies by hours, days of the week, and years. The Laws of 1655 are vague in this particular, but they give a more definite statement concerning the religious exercises. From the two the outline given below is obtained.

In arranging the material, I have followed the traditional (and I believe correct) view that Harvard, like Emmanuel College in Cambridge, was founded primarily for the education of the clergy; its founders “dreading to leave an illiterate Ministery to the Churches, when our present Ministers shall lie in the Dust.”805 If we accept this view, the significance of each part of the programme at once becomes apparent. The religious exercises and the study of the Bible formed the center of the scheme; the other subjects were such as aided the student, first, to interpret the Bible correctly for himself; and second, to expound to others, and to defend (in public debate if need be) his interpretation.806 From this point of view the studies and exercises fall naturally into six groups: 1. The practice of piety. 2. The study and analysis of the Bible. 3. “The principles of Divinity and Christianity.” 4. The mastery of the languages necessary to read the Bible in its original tongues — Greek, Hebrew, “Chaldee” (Aramaic), and Syriac. 5. Auxiliary studies — the arts and philosophies, history, and politics—necessary to correct interpretation of the Bible by the student. 6. Studies and exercises necessary to effective exposition and defense of one’s interpretation — rhetoric, declamations, disputations, repetition of sermons, commonplaces. The information given by the documents of 1642 and 1655 is most compactly shown in the following summary. The source is indicated by the dates in parentheses as (1642) or (1655).

“Lawes About Holy Dutyes Scholasticall Exercises and Helps of Learning” (1655)807

- I. The Practice of Piety.

- (1) Private prayer: “Let every Student be plainly instructed, and earnestly pressed to consider well, the maine end of his life and studies is, to know God and Jesus Christ which is eternall life, Joh. 17. 3. and therefore to lay Christ in the bottome, as the only foundation of all sound knowledge and Learning.

“And seeing the Lord only giveth wisedome, Let every one seriously set himselfe by prayer in secret to seeke it of him Prov. 2, 3.” (1642)

- (2) Attendance at Chapel twice daily: “Seing God is the giver of all wisedome, all & every Scholler (besides private prayers wherein every one is bound to aske wisedome) shall bee present Morning and evening at publique prayers at the accustomed houres viz ordinarily at six of the clocke in the Morning from the tenth of March at Sun rising and at five of the Clocke at Night all the yeare long.” (1655)

- (3) Public repetition of sermons in the Hall by the students in turn, “that so with reverence & Love they may retaine God & his truths in their minds.” On Saturday evenings “an account of their profitting by the Sermons preached the weeke past.” (1655)

- (4) Attendance on Sundays at services of the local church, where “gallery room” was reserved for the students.

- (1) Private prayer: “Let every Student be plainly instructed, and earnestly pressed to consider well, the maine end of his life and studies is, to know God and Jesus Christ which is eternall life, Joh. 17. 3. and therefore to lay Christ in the bottome, as the only foundation of all sound knowledge and Learning.

- II. Study and Analysis of the Bible.808

- (1) “Every one shall so exercise himselfe in reading the Scriptures twice a day, that he shall be ready to give such an account of his proficiency therein, both in Theoretticall observations of the Language, and Logick, and in Practicall and spirituall truths, as his Tutor shall require, according to his ability; seeing the entrance of the word giveth light, it giveth understanding to the simple, Psalm, 119.130.” (1642; repeated with omission of the last clause in 1655.)

- (2) “It is appointed that some part of the holy Scripture be read at morning & evening prayer viz some part of the Old Testament at Morning, & some part of the New at Evening prayer on this manner.

“That all students shall read the Old Testament in some portion of it out of Hebrew into Greeke, and all shall turne the New Testament out of English into Greeke, after which one of the Bachelors or Sophisters shall in his Course Logically analyse that which is read, by which meanes both theire Scill in Logicke, and the Scriptures and the Scriptures originall Language may be increased.” (1655)

- III. Divinity (1642).

- (1) “Divinity Catecheticall”809 at eight o’clock Saturday mornings.

- (2) Commonplaces at nine o’clock Saturday mornings (see “Rhetoric,” group VI, no. 2, below).

- (3) Analysis of the Bible (see group II, no. 2, above).

- (4) Study of systematic theology: manuals of Ames and Wollebius (specified first in the list of 1723, but probably used before 1701).

- IV. “The Tongues” (1642).

- (1) Greek.

- (a) Grammar.

- (1) Etymology and syntax with “practice . . . in such Authors as have variety of words.”

- (2) Prosody and dialects, with “practice in Poësy, Nonnus, Duport, or the like.”

- (b) Composition.

- (1) “Perfect their Theory” (i.e., principles of “style”).

- (2) “Exercise Style, Composition, Imitation, Epitome, both in Prose and Verse.”

- (2) Hebrew: grammar, with “practice in the Bible,” i.e., the Old Testament.

- (3) Chaldee: grammar, with practice in the books of Ezra and Daniel.

- (4) Syriac: grammar, with practice in the Syriac version of the Gospels, or the New Testament as a whole, edited by Martin Trost.

- (a) Grammar.

- (1) Greek.

- V. Auxiliary Studies: the Arts and Philosophies, History, and Politics.

- (1) Logic

- (2) Physics

- (3) “The Nature of Plants”

- (4) Metaphysics

- (5) Ethics

- (6) Politics

- (7) History

- (8) Arithmetic

- (9) Geometry

- (10) Astronomy

- VI. Exposition and Defence of Interpretations of the Bible.

- (1) Rhetoric: lecture to all students at eight o’clock on Fridays (1642).

- (2) Declamations: a declamation by each student once a month (1642), at nine o’clock on Fridays (once in two months, 1655). The rest of that day “vacat Rhetoricis studiis” (probably for, rather than from, rhetorical studies). The time might be given, e.g., to the composition or practice of the declamation which the student must deliver once a month before the members of the college. The technique of oratory, as given in the lectures on rhetoric and in such books as Clarke’s Formulae Oratorium or Morellus’s Enchiridion Oratorium could have been applied in these exercises.

- (3) Disputations: disputations (i.e., debates) were stated exercises, one hour in length, for each class on Monday and Tuesday afternoons, in the programme of 1642 (twice a week in 1655). The questions or theses for debates were presumably chosen from the subject — logic, physics, ethics, etc. — which the class was studying in the morning of the same day.

The rather intricate technique of disputation must have been studied, somewhat as principles of argumentation are studied today. Farley’s Disputationum Academiarum Formulae, and especially Keckermann’s Opera Omnia, I, chapter vii, display the technique in detail.

- (4) Repetition of sermons (see group I, no. 3, above).

- (5) Commonplaces: systematic discussions of some point in divinity in the form of a (supposedly) short sermon, which might, however, run to an hour in length.810 See Maccovius, Loci Communes, and Musculus, Commonplaces of the Christian Religion, pp. 416 and 421, below.

“There shall be a Common place handled in Divinity . . . once a Fort-Night, the President beginning, and the Masters of Art & Senior Bachelours following according to their Seniority; Wherein the President & Fellows shall take Care that heterodox opinions & Doctrines bee avoided & refuted & such as are according to the Analogy of Faith be held forth & Confirmed.” (1655)

Inspection of this list revealed some twenty-five subjects in which the use of text-books might be expected. I assumed that these subjects were actually taught at one time or another, and that text-books were used in connection with each. The problem was to identify those books.

The prospect of a solution was not hopeful. For some time I was held back by the thought that all the books of the Harvard library were destroyed by the fire of 1764, and that therefore none of those existing in the seventeenth century would be there. It simply did not occur to me that the gifts made by alumni to replace the lost volumes might include such books; still less did I imagine the way in which, if found, any evidence could establish their use as Harvard text-books.

Another difficulty lay in the condition of the college library in 1909. It had expanded far beyond the capacity of Gore Hall, and many thousands of volumes were stored temporarily in the basements of other buildings; some tens of thousands more, unclassified on the shelves, were in stacks called by Professor Emerton “the Dump.”811 The card catalogue also presented obstacles; it was mainly an author catalogue, and although there was also a classification by subjects, it was hopelessly inadequate for my purpose. I could only cruise along the several miles of shelves, looking at old books in the hope of finding a clue. In this state of affairs my attention was called to a pile of such books in the basement, and among these the clue was found. The book was a copy of Aldo Manuzzio’s Phrases Linguae Latinae (London, 1636).812 On its fly-leaves were the dated signatures of John Whiting and Joseph Whiting, the undated autograph of one of the two Joseph Cookes — all Harvard undergraduates in the 1650’s — and a bookplate (dated 1693) of Elisha Cooke, A.B. 1697.

Phrase-books of this type were constantly used in European schools and universities of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the composition of Latin orations, declamations, and disputations; hence it seemed possible, if not probable, that the book in hand was actually used at Harvard in the 1650’s.813 And naturally this discovery suggested further search for books autographed and dated by Harvard students of the seventeenth century. The assumption was that books on the various subjects of the curriculum, owned by these men during their student years, were used in their study of the subjects concerned. The use of auxiliary books, such as the phrase-book first discovered, was naturally suggested; and further exploration revealed an unexpected number and variety of such works.

The condition of the Harvard College Library, and various other circumstances, including the World War, combined to postpone further investigation until 1920. Meanwhile the Widener Library had been built, and the arrangement of books therein made further search easily possible. The original plan was simply to take from the shelves all books (earlier than 1701) in logic, ethics, metaphysics, and the other subjects listed above, and examine them for dated signatures, inscriptions, or other evidences of ownership by Harvard men during their years as undergraduates or as candidates for the degree of A.M. Exploration soon spread beyond these subjects to other possible fields. However, neither the finding of the books nor the interpretation of the inscriptions proved to be as simple a matter as the preceding sentences imply.

The work has gone on at varying intervals in the few hours which could be spared from many other duties, and it is not yet complete. The search has been extended to the libraries of the Andover-Harvard Theological Seminary, the American Antiquarian Society, the Massachusetts Historical Society, the Boston Athenaeum, Yale University, and Brown University, and to the Boston Public Library (especially the Prince collection) and the New York Public Library.814 More than four thousand volumes have now been examined. Various graduate students have assisted me in this work. Particular mention must be made of Mr. Kenneth Viall, who in 1920 examined about a thousand volumes and first identified many of the books listed in this article.

The main results of this long-continued search are given in the two detailed lists below. These are (1) an alphabetic arrangement of the books by authors; (2) an arrangement of the authors according to the subject-matter of the books cited in the first list, following the order given above. A list of student owners, with the titles of books owned by each, may be compiled from the index to this volume. The results may be stated more briefly. In contrast to the four titles suggested by the seventeenth-century sources available in 1909, some 228 items have now been identified by dated signatures as actually the property of seventeenth-century Harvard students during their college years. Thirty others, each containing at least two undated student signatures and each supported by additional evidence, have been included as “probables”; twenty-five or more, each with one undated signature and other evidence, have been listed as “possibles.”815

As to content, these books may be divided into three groups. First are the text-books. The list includes text-books on all the subjects mentioned in the Order of Studies of 1642, except politics, “Divinity Catecheticall,” and the “Nature of Plants.” Those best represented are the Bible — nineteen examples of the whole, or parts, in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, or “Chaldee”; divinity — twenty titles, besides two systematic treatises in seven and eight volumes respectively; logic — twenty-one titles, three of which have three examples each; physics — eleven titles, of which one (Magirus) appears in six examples; metaphysics — nine titles, one in duplicate; ethics, five titles; astronomy, five titles; and Hebrew grammar, six titles, one of which (Schickard) appears in five examples.

Reference books of various types make up the second group. Among these are phrase-books, collections of proverbs, and specimens of composition, all useful in the writing of themes, orations, and declamations; lexicons for Hebrew, “Chaldee,” Syriac, Greek, and Latin; dictionaries of classical and oriental antiquities; works on chronology; systematic treatises on theology; and encyclopaedias.

The third group includes a few works not directly related to the programme of studies, but such as might more or less casually drift into a student’s library.

The acceptance of these volumes as text-books and reference books used at Harvard in the seventeenth century is based mainly upon two lines of evidence:816 first, they deal with, or are related to, the subjects of the programme of studies as given in the sources cited at the beginning of this paper. Second, they contain the signatures of men recorded in the Quinquennial Catalogue as students of this period. These signatures, of course, furnish the decisive evidence. Without them we should still be in almost complete ignorance; with them, we can speak with confidence.

This evidence is certainly impressive, both in the number of men who have written their names in these volumes, and in the number of college classes represented by them. It is presented in detail in the description of each volume in the alphabetic list of authors below.

If the evidence derived from the signatures were to be viewed statistically, it would be seen that 177 (nearly 38 per cent) of the 465 men who took the A.B. degree between 1642 and 1701 wrote their names in these volumes.817 Of these men, 115 (about 25 per cent of the total number of seventeenth-century A.B.’s) dated their signatures during their college years. The signatures of the other sixty-two, undated, have been accepted, for reasons varying from case to case, as probably also written during their student days.818

The distribution of these men by classes is no less surprising than the number whose signatures have been found. In the sixty-year period 1642–1701, fifty-five classes were graduated.819 No less than forty-four of these, beginning with the first class (1642), are represented by dated (and thirty-one of the forty-four also by undated) signatures of one or more of their members. Four other classes (1649, 1659, 1668, 1675) are represented only by undated signatures, but these were probably written during the college years of the men concerned.820

Dated and undated inscriptions taken together, the decade of the 1640’s is represented by signatures of five (or possibly six) of the thirty-six men who took their degrees in that period. Similarly, twenty-four of the seventy-seven A.B.’s in the 1650’s; thirty-two of the seventy-three in the 1660’s; twenty-one of the forty-eight in the lean 1670’s; thirty-three of the seventy-two in the 1680’s; and forty-five of the 145 in the prosperous 1690’s signed their names in the books now identified — a surprisingly even distribution. Some classes are represented by half, or even more than half, of their members: e.g., five out of ten in 1651 and in 1669; one of the two members of the Class of 1655; five out of seven graduates in 1657; three out of four in 1666; and all three members of the Class of 1683.

The persistent use of some of the books in the list is shown in two ways: by a succession of dated signatures in individual volumes, and by duplicate copies dated at different periods. An example of the first is the 1521 edition of the Hebrew Pentateuch, owned by John Remington in 1657, then by his son John in 1688; by Moses Hale in 1696; by Samuel Moodey, 1697; by John Hale about 1715; by Oliver Peabody, 1716; by John Hancock before 1766, and given by him to John Winthrop in 1766. Similar records exist in a copy of Burgersdicius’s Idea Moralis (1650); Cicero’s Orations, Vol. II (1606); and Homer’s Iliad (1672), in which the eight signatures run from 1680 to 1792. Among duplicate copies dated at different times are the Meditationes of Descartes, of which Zechariah Brigden owned a copy in 1658 and Daniel Henchman another in 1696. Keckermann’s Systema Logicae was owned by Increase Mather in 1654; three other copies have been identified, with ten seventeenth-century Harvard owners of later date, ending with Timothy Cutler of the Class of 1701. Maccovius’s Metaphysica, owned by Increase Mather in 1655, appears in two other copies, owned respectively by John Hancock (the Lexington minister) in 1691, and Tutor Henry Flynt in 1692. Magirus’s Physiologia is represented by six copies, in which the earliest signature appears to be that of John Wilson, possibly of the Class of 1642; the latest that of Daniel Russell, A.B. 1699. A dozen other Harvard owners had these books in the intervening years. Russell’s copy was transferred to Yale where it was owned by John Wick, Isaac Wolcott Chauncy, and finally, in 1723, by Joseph Buckingham. Almost as impressive are the five copies of Schickard’s Horologium Hebraeum (Hebrew in Twenty-four Hours!). Nehemiah Ambrose, of the Class of 1653, signed the earliest of these. A dozen later Harvard signatures in the five copies, ending with that of Mather Byles, of the Class of 1725, mark successive years of the use of this book. Byles’s class would have used Schickard in their freshman year, 1721–22, and it must have been the last to do so, since the grammar of Judah Monis was introduced in 1722.

As interesting as the persistency of certain texts is the interval between the date of publication of some books and their first appearance at Harvard. In a few instances (e.g. Ames, Lectiones in Omnes Psalmos) the book was sent over shortly after publication, but in most cases the interval was anywhere from twenty to one hundred years. Where were these books during those years? The question suggests an interesting subject for research.

In view of the facts which have been cited, the lists which follow, and much evidence which I have not space to exhibit, it seems reasonable to infer that, among the books identified, approximately two hundred volumes which are definitely text-books form a collection fairly representative of those in use by Harvard undergraduates of the seventeenth century. One naturally inquires whether the recovery of the six thousand or more volumes now lost, which must have been owned by these men, would radically change the picture given us by this little group of survivors. There are reasons for believing that it would not. It appears that the books now identified, taken in connection with the few surviving notebooks kept by students, the Commencement Theses, and other documents of the period, give us a fairly accurate idea of the field of learning cultivated by our predecessors of nearly three centuries ago.

As for the little group of reference books, there is less assurance that these are representative; but the list is easily supplemented from the Boston booksellers’ lists of the 1680’s, from the various catalogues of colonial libraries now available, and from the libraries mentioned in this article.

About thirty places of publication are represented in this list, but eleven of them account for most of the titles: London (65), Amsterdam (27), Geneva (17), Frankfort (14), Cambridge (11), Leyden (9), Oxford (8), Hanover (7), Antwerp (5), Basle (5), Herborn (5).

Some light on the ways in which these books reached Harvard is furnished by Thomas Goddard Wright, Literary Culture in Early New England, 1620–1730 (1920). The biographies of their writers (about one hundred in number) furnish most illuminating material for this study; but for these the reader must be referred to the English, German, and French biographical dictionaries. Similarly illuminating, the biographies of the owners of these long-forgotten volumes must be sought in the invaluable pages of John Langdon Sibley’s Harvard Graduates.

With these materials in hand it is now possible to write a more authentic and more detailed history than has hitherto been written of the studies and exercises in Harvard College in the seventeenth century. And surely that history must leave us with profound respect for the learning of those Puritan Englishmen who maintained through the troublous years of that century standards which brought recognition of the Harvard degree from Cambridge and Oxford.

List by Authors

In the following list all copies of the Old and New Testaments, or parts of them, are placed under the heading “Bibles.” The other books are arranged alphabetically by authors or (in a few cases) by titles. The author’s name is usually given in its native form, followed in some instances by the Latinized version. In cases in which the latter is the better known, the reverse procedure is followed; thus, Burgersdicius rather than Burgersdyk; Chytraeus rather than Kochhoff; Clenardus rather than Cleynaerts; Comenius rather than Komenski. The titles of the books are usually given in abbreviated form, but enough has been included to indicate the nature of the work. No attempt has been made, however, to follow the original capitalization and punctuation. Needless to say, the title-page of those days usually amounted to an appetizing table of contents, coupled with some skillful advertising. Too much space would be required for complete reproduction of this interesting material, but a study of the phrases used to attract the buyer is well worth while.

The place of publication has been given in English rather than in the Latin form commonly used by the publishers (“Copenhagen” instead of “Hafnia,” “Utrecht” rather than “Ultrajectum,” etc.); and the date in Arabic rather than Roman numerals. The superior “a” which follows certain titles indicates that these books are listed as “probables”; similarly, superior “b” indicates those listed as “possibles” (see p. 375, above). Present locations of the books listed are indicated according to the key given below.821

The dated signature or signatures which indicate ownership of the book by one or more Harvard students of the seventeenth century come next, in smaller type. The dates in those books ranked as “certains” must fall, as noted above, within the seven-year period between the student’s entrance as a freshman and his attainment of the A.M. degree. Examples of other signatures, dated or undated, and other inscriptions of interest are included. Each item is transcribed exactly and placed in quotation marks. The date of the student’s A.B. degree is given in brackets in each case, including even those later than 1701. Names not followed by the A.B. date are those of men who did not attend the college, or who did not take a degree.

No attempt has been made to print all the signatures in these books. Not infrequently later owners crossed out the names of earlier ones; many of these have been deciphered and are here printed, but others, effectually blotted out, remain to tantalize the investigator. A serious effort has been made to record at least one example of each decipherable signature, but it has not been possible to indicate the position of this signature in the volume. In general, the names are to be found on both front and back fly-leaves, on the insides of covers, on title-pages, on the margins of prefaces, and occasionally well within the numbered pages of the book. They may be hard to find, written as they often are at all angles or upside down, in faded ink, in obscure corners, or in a microscopic hand, or hidden by a mass of later scrawls and scribbles. Anyone who wishes to follow the trail of the present writer is hereby warned of the difficulties in the way.

johann heinrich alsted

Cursus Philosophici Encyclopaedia libris XXVII complectens universae philosophiae methodum, serie praeceptorum, regularum & commentariorum perpetuâ. Herborn: 1620.

bpl (Prince).

“Samuell Niless Book July 25th 1697 pr 9s” [A.B. 1699]

Johannis-Henrici Alstedii Encyclopaedia. I. Praecognita disciplinarum. II. Philologia. III. Philosophia theoretica. IV. Philosophia practica. V. Tres superiores facultates. VI. Artes mechanicae. VII. Farragines disciplinarum. 7 vols, in 4. Engraved t.p. Herborn: 1630.

hcl.

“Petro Ruck [A.B. 1683] hanc Encyclopædiā Alstedianā dono dedit Reverendissimus Crescentius Matherus vigesimo octavo die Maij Anno Domini 1683 Preciū 4. vol. 218s”

“Johannes Ballantine hunc librum jure tenet Novembris 23o 1691” [A.B. 1694]

“Johannes Barnard me jure tenet 1799 [sic; A.B. 1700]

The same signatures are repeated in volumes II–IV, and in the back of volume III is “Joseph Pynchon me tenet 1663” [A.B. 1664]

Methodus SS. Theologiae in VI. libros tributa: in quorum I. Theologia naturalis. II. Theologia catechetica. III. Theologia didactica seu loci communes. IV. Sotyrologia seu scholae tentationum, & casus conscientiae. V. Prophetica, ubi rhetorica & biographia ecclesiastica. VI. Theologia acroamatica. Autore Iohan. Henrico Alstedio. Cum indice rerum & verborum. Hanover: 1619.

aas.

“Cottoni Matheri Liber 1681” [A.B. 1678]

Pastor Conformatus ab Henrico Bullingero: officium boni pastoris, totius Christianae religionis elementa. Productus in lucem a Johan-Henrico Alstedio. Frankfort: 1613.

mhs.

“Crescentius Mather, 1655” [A.B. 1656]

Bound with Talasius, Epitome Logici, q.v.

Ioan. Henrici Alstedii Scientiarum Omnium Encyclopaediae Tomus III, IV. Lyons: 1649. (Plate I.)

bpl (Prince).

“E libris Josephi Browne octob: 2: 1668” [A.B. 1666]

“Lege, Intellige, Vive, J.B: Pret: Bos: 2 folo 03, 12, 0. 1668”

Theologia Didactica, Theologia Prophetica. 8 vols. Frankfort, Hanover: 1616–1627.

aas (Mather).

Some of them inscribed: “Cottoni Matheri Liber, 1681” [A.B. 1678]

Johannis Henrici Alstedii Thesaurus Chronologiae in quo universa temporum & historiarum series in omni vitae genere ita ponitur oboculos, ut fundamenta chronologiae ex S. Uteris & calculo astronomico eruantur, & deinceps tituli homogenei in certas classes memoriae causadigerantur. 2nd edition, Herborn: 1628.

bpl (Prince).

“J. Sewall”

“Daniel Russell His Book 1670” [A.B. 1669]

A copy of the fourth edition (Herborn, 1650) in bpl (Prince) bears the undated signatures “Crescentii Matheri Liber,” and “Byles.”

William Ames

De Conscientia et eius iure vel casibus. Engraved t.p. Amsterdam: 1630. (Plate II.)

hcl.

“Richardus Wensley me Suis addidit 1 Januarii, 1681” [A.B. 1684]

Another edition. T.p. missing. Amsterdam: 1680.

hcl.

“pretium Is 6d”

“Joseph Dassett me jure inter suos numerat Anno Domini 1685” [A.B. 1687]

“Nathaniel A. Haven Junr e Libris avi ejus honorati Revdi Samuelis Haven [A.B. 1749] S.T.D. anno S.N. 1806”

Lectiones in omnes Psalmos Davidis: in quibus per analysim, &, ubi opus est, per quaestiones sensus dilucide ac succincte enodatur. London: 1647.

mhs.

“Samuell Willys His Booke sent from England, Anno Dom: 1650” [A.B. 1653]

“S. Phillips pretium 0–3–6”

Bookplate (mut.) of Samuel Phillips, 1707 [A.B. 1708]

“Obadiah Ayer [A.B. 1710] 1717 Donum Rev. Samll. Philips ult. 10er 1717”

This book fully illustrates the meaning of the hitherto unexplained requirement in the college statutes of the seventeenth century that candidates for the A.B. degree must be able to “resolve [the Scriptures] logically.” Compare the works of Piscator on various books of the Old and New Testaments. Each of these contains an “analysis logica” of the book under consideration.

Medulla S.S. Theologiae. Amsterdam: 1628. (Plate III.)

aas.

“preciū 2s 4d”

“Thomas Cheever me suis addidit Junii 25 1674” [A.B. 1677]

“Johannes Burt [A.B. 1736] ejus Liber Ex dono Avi sui Reverendi D. Thomæ Cheever A.M. 1736.”

Another edition. London: 1629.

aas.

Bookplate:822 “Joseph Eliot his Book Anno Domini 1678” [A.B. 1681]

“Joseph Eliot’s book”

“William Whitaker his Book”

“W. Williams 1714”

“Joshua Gee” [A.B. 1717]

Technometria. Guilielmi Amesii magni theologi ac philosophi acutissimi philosophemata. Technometria duplici methodo adornata, cui jure cognationis nunc adjunguntur, ejusdem adversus metaphysicam atque ethicam disputatio theologica. Item, logicae verae demonstratio & adumbratio, ac logicae theses, res ejusdem artis ordine enucleantes. Amicus Plato, amicus Aristoteles, sed magis arnica Veritas. Cambridge: 1646.

aas.

“Cottoni Matheri Liber 1681” [A.B. 1678]

Alexander Aphrodisiensis

Quaestiones Alexandri Aphrodisei Naturales, De Anima, Morales: sive difficilium dubitationum & solutionum libri IV nunc primum in lucem editi. Gentiano Herueto Aureliano interprete. Basle: 1548.

bpl (Prince).

“Nath Saltonstall 30 (6) 56” [A.B. 1659]

Aphthonius

Aphthonii Progymnasmata, partim à Rodolpho Agricola, partim à Johanne Maria Catanaeo, latinitate donata. Cum scholiis R. Lorichii. London: 1611.a

aas (Mather).

“John Eliot his Booke” [A.B. 1685]

“John Oliver” [A.B. 1685]

“S. Matheri, 1761” “Rich. Carter” “Walter Carter”

“Jonathan Ting his booke” “Recompense Tinge” “Peter Tinge” “Walter Carter is the true honer of”

Originally bound at the end of this volume was the advertisement of “a publike School to youth at the signe of the Red Lion over against the west end of Paul’s.” The advertisement is not dated, but its date appears to be about 1654, since “King” in “God save the King” at the end is crossed out, and “Protector” is written in. This advertisement has been removed and is now classified in the aas catalogue as a broadside.

Another edition. London: 1636.a

hcl.

“Jonathan Burr his book” [A.B. 1651]

“John White his booke” [A.B. 1698]

“Edmund” [Goffe? A.B., 1690] “John Goffe”

“Swan” on p. 2 of index

“domæ manu 1694” on p. 328

Another edition. London: 1655.b

hcl.

Given to the hcl by John Barnard [A.B. 1700]. Possibly owned by him in college.

Arias Montanus. See Bible, Hebrew O. T.

Aristotle

Commentarii Collegii Conimbricensis, Soc. Jesu, in quatuor libros de Coelo, Meteorologicos & Parva Naturalia, Aristotelis Stagiritae. Cologne: 1603.

hcl.

“Cotton Mather 1676” [A.B. 1678]

“Johannis Barnard Liber 1697/8” [A.B. 1700]

This, and the corresponding Commentarii Collegii Conimbricensis in tres libros de Anima (of which both the hcl and the bpl have copies that belonged to Harvard graduates) consisted of the Greek text of Aristotle with Latin translation, an extensive gloss by the Jesuit Doctors of the University of Coimbra, and quaestiones on each chapter, argued syllogistically.

Epitome Doctrinae Moralis, ex decern libris Ethicorum Aristotelis ad Nicomachum collecta, pro Academia Argentinensi, per Theophilum Golium, adjectus est ad calcem aureus ejusdem Aristotelis libellus de Virtutibus & Vitiis, Symone Grynaeo interprete. Cambridge: 1634.

bpl (Prince).

Johannes Avenarius (Johann Habermann)

Liber Radicum seu Lexicon Ebraicum. Wittenberg: 1589.

bpl (Prince).

“Joseph Gerrish [A.B. 1669] his Booke Bought of Mr John Paine Anno Domini 1666 Aprill 13th”

“Joseph Gerrish his Booke 1667”

Robert Baillie (1599–1662)

Operis Historiciet Chronologici libri duo; in quibus historia sacra & profana compendiosè deducitur ex ipsis fontibus, à creatione mundiad Constantinum Magnum. Amsterdam: 1668.

bpl (Adams).

“Compensatius Wadsworth Ejus Liber An. Sal. 79” [Class of 1679]

“Benjamin Wadsworth [A.B. 1690] me suum vocat anno dom. 1686 October 20 . . . given by his brother Recompence”

“N. Williams book bought of Mr. Wadsworth April 1 1695 pr 6/–” [A.B. 1693]

Another copy.

Yale.

“Grindall Rawson’s Booke” [n.d.; A.B. 1678]

“Jacobus Pierpontus [A.B. 1681] me Bibliothecæ suce commendatum fecit: Ter; Calend; Maii, An, Dom, 1679”

John Barclay (1582–1621)

Jo: Barclaii Argenis. Editionovissima. Amsterdam: [1642].b hcl.

“pretium 3s”

“Michaell Wigglesworth me jure possidet” [A.B. 1651]

“Joseph Sewall” [A.B. 1707]

“Edward Wigglesworth 1726” [A.B. 1710]

Caspar Bartholin (1585–1630)

Casparis Bartholini Malmogii Dani Philosophi Enchiridion Physicum ex priscis & recentioribus philosophis. Strassburg: 1625.

bpl (Prince).

“Sum ex Libris Nathaniel Saltonstall Oct: 13 1695” [A.B. 1695]

“John Woodbridge” [there were graduates of that name in 1664, 1694, and 1710]

“Every man at his best estate is altogether vanity”

Enchiridion Metaphysicum. See Magirus, Physiologiae, etc.

John bastwick

Πραξεις τωυ Ἐπισκόπων, sive Apologeticus ad Praesules Anglicanos. Autore Johanne Bastwick, M.D. n.p.: 1636.

aas.

“Joseph Taylor ejs Liber An: Dom. 1671” [A.B. 1669]

“John Tailor His Booke 1696” [A.B. 1699]

“John Holman his book” [A.B. 1700]

Friedbich Beurhaus (Beurhusius)

In P. Rami Dialecticae libros duos Lutetiae anno LXXII postremo sine praelectionibus aeditos, explicationum quaestiones: quae paedagogiae logicae de docenda discendaque dialectica. Pars prima. London: 1581. [And] De P. Rami Dialecticae praecipuis capitibus disputationes scholasticae & cum iisdem variorum logicorum comparationes: quae paedagogiae logicae pars secunda, qua artis Veritas exquiritur. London: 1582.

hcl.

“Elisha Cooke” [A.B. 1657 or 1697]

“Lord” “John D [ ]”

“Joseph Cooke [A.B. 1660 or 1661] me suis addidit: July 1659”

Marginal and interlinear ms. notes in the text, in more than one hand.

Beza. See last item under Bibles.

Bible–Hebrew O.T.

[Pentateuch]823 חמשה חומשי תורה ed. Adelkind. Venice: Bamberg, 1521.824

aas.

“John Remington His Booke 1657”

“Jo Remington’s Book Anno Christi 1688” [A.B. 1696]

“Moses Hale [A.B. 1699] Eius Liber Bought of Remington Decemb: 20th: 1696, Pret: 16s”

“Samuel Moodey Anno 1697” [A.B. 1697]

“John Hall” [A.B. 1719]

“Oliver Peabody [A.B. 1721] Ejus Liber. Bought of Mr Hale jun 1716/17 pret. 16s”

“John Winthrop [A.B. 1765 or 1770] Feby 20, 1766, the gift of John Hancock Esqr”

Plate IV, showing a fly-leaf of this book, furnishes an illustration of students’ inscriptions and scrawls.

[Pentateuch] חמשה חומשי תורה. Antwerp: Plantin, 1566.825

aas.

“John Hancock [A.B. 1689] Thomas Swan [A.B. 1687] Ejus Liber Anno Dom.”

“Hie liber meus est si quisquis fortè requirit

Nomen subscriptū perlege quæso meū.

Johannes Poole” [Class of 1696]

[Pentateuch] חמשה חומשי תורה.a Geneva: Rovière, 1618.826

aas.

“John Tyng His book September 31 [sic] 1688” [A.B. 1691]

“Andrew Gardner 169[ ]” [A.B. 1696]

“John Taylor 1696” [A.B. 1699]

“Dudley Bradstreet” [A.B. 1698]

Another copy.

aas.

“William Partrigg His Book Anno; Dominj 1686” [A.B. 1689]

“Josephus Wingurtus”

Bound in wrong order: the title-page is numbered p. 122 in ms.

Another copy.

aas.

“Isaaci Chauncei liber 1690 Julii” [A.B. 1693]

“Solomon Williams His Book Anno 1717” [A.B. 1719]

“John Hubbard Ejus Liber 1750” [A.B. Yale 1747]

“The Revd Mr John Hubbard’s Book. Minr of Cts Ch at Northfield”

Biblia Hebraica. Eorundem Latina interpretatio Xantis Pagnini Lucensis Benedicti Ariae Montani. Geneva: 1619.827 [Bound with:] Novum Testamentum Graecum. n.p. 1619.

hcl.

“E libris Josephi Browne Octob: 1. 1668 Lege, Intellige, Vive. Pret: Lond: 01.15.00. 1668” [A.B. 1666]

Hebrew, with interlinear Latin translation by Sante Pagnino from the Antwerp Polyglot edited by Arias Montanus. Pasted into this copy are the inscriptions from another, which the hcl sold as a duplicate, c 1825. That duplicate belonged to George Phillips, the first minister of Watertown (d 1644), who gave it to his son Samuel Phillips (A.B. 1650), the grandfather of Samuel Phillips (A.B. 1734), who also used it in college.

Biblia Hebraica, eleganti charactere impressa. Editio nova. Amsterdam: 1635.828

hcl.

“Samuel Sewall Novembr’ 26, 1687”

“Hunc Librum Dudleius Bradstreet [A.B. 1698] Tenet A. Domini 1695.”

“John Legge’s Hebrew Book Anno Dom: 1687/8” [A.B. 1701]

“Benjamin Wadsworth’s Book, given by Mr. John Legg Jan 4 1706/7”

Second and most important of the editions prepared by Menasseh ben Israel, the famous Jewish Rabbi of Amsterdam.

Another copy. Interleaved and bound in 2 vols. Andover-Harvard.

“Samuel Vassall me jure tenet Jan. 1692” [A.B. 1695]

“Sed potuit Tho: Phips 1693” [A.B. 1695]

Later marks of ownership of Joseph Buckminster (Yale 1770), William Mather (Yale 1773), Samuel Harris (died as an undergraduate at Harvard, 1812), John Gorham Palfrey the historian, and Andrew Preston Peabody, who gave these volumes to the Divinity School Library in 1888.

[The Twenty-four (books of the Old Testament)] עשרים וארבעה. Amsterdam: 1638–39.829

Andover-Harvard.

“Huius Libri Donatori Benevolentissimo, Reverendissimo ac Doctissimo Domino Crescentio Mathero, Gratias Multas et maximas agit, Aget Agatque Donatus Indignissimus Nathaniel Clap. Januarii 21, 1687/8” [A.B. 1690]

The third edition prepared by Menasseh ben Israel.

Andover-Harvard.

“Me omnes inspicientes Wilhelmi Brinsmeadi [Class of 1655] librum appellate Emptum Augusti 2do 1651”

“Liber Abijæ Thurston 1746” [A.B. 1749]

“Edmund Noyes his Book 1746” [A.B. 1747]

The Hebrew Text of the Psalmes and Lamentations, revised and corrected according to the best of Plantin and Stephan’s Impressions. By William Robertson. London: 1656.b

aas.

“Thomæ Berry liber” [A.B. 1685]

“he is a rouge and a great”

“Benjamin Marston 1711” [A.B. 1715]

Bible—Greek

Της Θειας γραφης, Παλαιας Δηλαδη και Νεας Διαθηκης, απαντα. Divinae Scripturae omnia. Frankfort: 1597.830

hcl.

“Simon Willard his booke 1692” [A.B. 1695]

Bookplate: “Simon Willard Hunc Librum Jure Tenet Julij 1. 1695.”

“Joseph Sewall 1730” [A.B. 1707]; who gave it to the hcl in 1764. Edited by Francois du Jon or Friedrich Sylburg.

Another copy.

bpl (Prince).

“Anthony Stoddard’s Booke Anno: Dom: Nati: Ies. Christ: 94” [A.B. 1697]

“Bought of Mr. I. K. November 25: Finis cum furcum Babilonium Geog.”

Bible—Greek O.T.

Ἡ Παλαια Διαθηκη κατὰ τοὺς Ἑβδομήκοντα. Vetus Testamentum Graecum ex versione Septuaginta.b London: 1653.831

hcl.

“Collegii Harvardi Liber 1676”

“John Leverett Ejus Liber 1696” [A.B. 1680]

“Thornæ Frink [A.B. 1722] Liber e Bibliotheca Harvardina 1734”

This book apparently belonged to the College Library, was used and claimed as his by John Leverett as a tutor, purchased from the Library by Thomas Frink, and again presented to the Library by Walter S. Hertzog (A.B. 1905) in 1905.

aas.

“Peter Thacher” [A.B. 1696?]

“Oxenbridge Thacher” [A.B. 1698]

“Peter Thacher [A.B. 1769] his Book by the Gift of his honoured Grandfather Oxenbridge Thacher Esqr September 19 1766”

“Zabdiel Adams [A.B. 1759] his Book Bought of Peter Thacher in the yeare 1769 Pretium £4.10.0”

There is an earlier erased signature (Edmund Davie? A.B. 1674) with the date 1666.

Bible—Greek N.T.

Της Καινης Διαθηκης απαντα. Novi Testamenti libri omnes, editi cum notis Roberti Stephani, Josephi Scaligeri, & Isaaci Casauboni. London: 1622.a

MHS.

“John Cotton His Booke Anno Domini 1649” [A.B. 1657]

“Witness all that in this writinge looke on the 8th day of . . . Aprill 1650 written by Elisha Cooke” [A.B. 1657]

“honorificicabilitudinitatibusque”

“honorificicabilitudinitatibusiter”

“Samuel Aspinwall is a knave”

Bible—Greek Apocrypha

Bibliorum pars Graeca quae Hebraice non invenitur; cum interlineari interpretatione Latina. Antwerp: 1612.

aas.

“Samuell Myles [A.B. 1684] est huius liberi verus possessor, ex dono Avi reverendi — March 8: 1683”

Bible—Latin O.T.

Testamenti Veteris Biblia Sacra, sive, libri canonici priscae Judaeorum ecclesiae Latini recens ex Hebraeo facti, ab Immanuele Tremellio & Francisco Junio. Hanover: 1603.832hcl.

“Caleb Cushing’s Book An: dom 1695” [A.B. 1692]

Bible—Latin N.T.

Novum Testamentum Interprete Theodora Beza.b London: 1659.833

mhs.

“Benjamin Colman” repeated on several pages [A.B. 1692]

“M. Byles” [A.B. 1725]

S. S. Biblia Polyglotta complectentia textus originales Hebraicos cum Pentat. Samarit: Chaldaicos Graecos versionumque antiquarum quicquid comparari poterat. Ex mss. antiquis undique conquisitis optimisque exemplaribus summa fide collatis. Edidit Brianus Waltonus S.T.D. 6 vols. London: 1657.

bpl (Prince).

[In vol. I:] “In the year 1724 I bought this with all the following volumes & Castelli [Polyglott] Lexicon of Mr. Samuel Gerrish Bookseller of Boston, for Thirty Pounds, who had bought them of Dr. Cotton Mather, who had a duplicate of them: & I paid sd. Gerrish Thirty Pounds for them:

as witness my hand

Thomas Prince”

“Nathanaelis Matheri Liber Martii 23rd 1683[/4]” [A.B. 1685]

[In vol. II:]

“Nathanaelem Matherum

Hoc Libro Donavit

Pater Suus Carissimus

Mensis Martii Die 23

Anno Christi

mdclxxxiii”

Bookplate in vols. III–VI: “Nathanielis Matheri Liber. Dedit Pater Suus Honorarissimus A.D. 1683”

The Hebrew and Latin are interlinear, and the “Versio Vulg. Lat.” is also given.

The “Castelli Lexicon” mentioned by Prince is also in the Prince collection, but contains no seventeenth-century Harvard signatures.

William Brattle (1662–1717)

Compendium Logicae secundum principia D. Renati Descartes catechistice propositum. P Gul. Brattle. In usū pupillorū. Bound ms. book, 72 pp.

hcl.

“Thomas Phips 1693” [A.B. 1695] who probably made the copy p. 3, printed label: “Joseph McKean, 1791” [A.B. 1794]

A Compendium of Logick, according to the modern philosophy extracted from Legrand & others, their systems. Per Dom: Brattle, in usum pupil. 1687. ms. 4o book of 18 leaves, bound up with ms. Morton’s Logic (see Morton).

mhs.

“Timothy Lindall His Booke 1692/3 [A.B. 1695] Incept: a Die 17: 12 et finit: Die 17 1 mensis”

An English translation of the Compendium Logicae, which serves to identify both with the “manuscript called the New Logick Extracted from Legrand and ars Cogitandi,” mentioned in Tutor Flynt’s list of studies. Another ms. copy (56 leaves 8o), transcribed by Thomas Prince in 1710, is in the mhs.

Caspar Erasmus Brochmand (Jesper Rasmussen Brochman)

Universae Theologiae Systema. Authore Casparo Erasmo Brochmand SS. Theologiae in Academia Regia Hafniensi Doctore. Ulm: 1658.

hcl.

“John Barnard Ejus Liber 1703” [A.B. 1700]

“Lege, Lege, deliberate Lege; premium munificum ea persolvet”

George Buchanan. See Büchler

William Buchan (Bucanus)

Institutiones Theologicae, seu locorum communium Christianae Religionis analysis Guilielmi Bucani SS. Theologiae in Academia Lausanensi professoris opera & studio. Geneva: 1625. (Plate V.)

aas (Mather).

“Crescentius Matherus”

“Cottonus Matherus 1676” [A.B. 1678]

Another edition. Geneva: 1630.

hcl.

“Elna Athaenaeus Chauncaius me suo addidit vaticano Ano Dom: 72:24. pret. 4s” [A.B. 1661]

“Sam. Phipps me suis addidit 29: 4: 74” [A.B. 1671]

“Simonis Bradstreet Liber, 1725” [A.B. 1728?]

Johann Büchler

Sacrarum Profanarumque Phrasium Poeticarum Thesaurus, opera Mro Ioannis Buchleri in Wicradt praefecti. Adjacent praeterea [Georgii] Buchanani Phrases. Editio decima tertia. London: 1642.a

hcl.

“Elisha Cooke his book” [A.B. 1657]

“Middlecott Cooke eius liber” [A.B. 1723]

Burgersdicius (franco burgersdijck)

Collegium Physicum, disputationibus XXXII absolutum; totam naturalem philosophiam compendiose proponens. Autore M. Francone Burgersdicio. Leyden: 1642.

hcl.

“CM.” “Johanno Barnard Hunc Librum dedit Cottonus Matherus 1700”

“Johannis Barnardi Liber: 1697/8” [A.B. 1700]

“John Ballantine” [A.B. 1694?]

“Lydia Ballantine” “Samuell Wade”

Idea Philosophiae Moralis sive compendiosa institutio. Amsterdam: 1650.

Brown University Library.

“Josiah Flint His Book 16 [62? or 91?]” [A.B. 1664]

“Henry Flint Ejus Liber Anno Domini 1699 Octob. [ ]” [A.B. 1693]

“Post Patrem possidet Josiah. Patre mortuo Succedit Filius 1691 Henry. Henry mortuo [1760] Succedit alienus 1762 Nathaniel Fisher. [A.B. 1763] Nathaniel Pecuniae causa vendidit Richardo Cary. [A.B. 1763] Richardus amico ven[didit] Johanni Scolly [A.B. 1764] a quo Nathaniel re[demit] & nunc possidet & semp[er] Possidebit Deo Juvant[e]”

The last entry is apparently in the hand of Nathaniel Fisher. A very remarkable record of ownership. Cf. similar records in the Venice edition of the Hebrew Pentateuch (1521), above, and in Cicero’s Orations (1606), below.

Fr. Burgersdicii Institutionum Logicarum libri duo. Ad juventutem Cantabrigiensem. London: 1651.

H. A. Larrabee, Esq.

“Geo. Curwin His book 1699” [A.B. 1701]

“R. Dana’s 1718” [A.B. 1718]

“Sam. Jenison” [A.B. 1720]

“Thomas Weld 1719” [A.B. 1723]

At the back, mostly in the same hand, are the names Angier, Bayley, Cotton, Cutler, Fessenden, and Loring — all classmates of Curwin.

Franconis Burgersdici Institutionum Metaphysicarum libri II. Opus posthumum. [Edited by Heereboord.] The Hague: 1657.b

aas.

“Joseph Dasset’s Book” [A.B. 1687] “Is 6d”

Johann Buxtorf (1564–1629)

Joann. Buxtorfii Epitome Grammaticae Hebraeae. London: 1653.

bpl (Prince).

“Ephraim Savage His Booke 1661” [A.B. 1662]

“medio tutissimus ibis”

Johannis Buxtorfii Epitome Radicum Hebraicarum et Chaldaicarum. T.p. missing; preface dated 1607.a

aas.

“Jn Dauis” [A.B. 1661?] “Mr Dauis me suis addidit”

“Jeremiah Peck me jure tenet Anno 61” [Class of 1657]

“Phineas Fiske nunc me jure possidet Anno D.”

Johannis Buxtorfi Lexicon Hebraicum et Chaldaicum. London: 1646.

bpl (Prince).

“Thomas dudly oweth this Booke to his cousin 1652” [A.B. 1651]

“Tho: Shepard [A.B. 1653] me tenet donum Dni Danforthi [A.B. 1643] 1651”

“Josiah Marshall his book 1716” [A.B. 1720]

Victor Bythner

Lyra Prophetica Davidis Regis sive analysis critico-practica Psalmorum in qua omnes & singulae voces Hebraeae in Psalterio contentae tam propriae quam appellativae ad regulas artis revocantur. Insuper harmonia Hebraei textus cum paraphrasi Chaldaea, & versione Graeca LXXII interpretum, in locis, sententiis discrepantibus, fideliter confertur. Cui ad calcem addita est brevis institutio linguae Hebraeae & Chaldaeae. London: 1664.

bpl (Prince).

“Ametius Angier [A.B. 1701] Hunc Librum vendicat. Si quis in hunc librum teneres convertit ocellos nomen subscriptum perlegat illemeum, 1698”

“Remington, Jno.” [A.B. 1696]

“Sam Mighill [A.B. 1704] Ejus Liber bought of Thomas Graves” [A.B. 1703]

“Nathaniell Fisher” [A.B. 1706]

“Sam: Mighill non est verus possessor hujus libri Benjamin Ruggles [A.B. 1724] est verus possessor hujus libri emtus a Samuelo Mighilo anno domini 1719”

bpl (Prince).

“Sam Sewall January 22 1684/5” [A.B. 1671]

“Joseph Sewall 1723” [A.B. 1707]

“Saml Hirst me jure tenet” [A.B. 1723]

John Ellerys hand did it in ye year 1731 /2” [A.B. 1732]

John Calvin

The Institution of Christian Religion translated into English by Thomas Norton. London: 1599.a

hcl.

“Empt: e [a?] Mag: [John?] Clark [A.B. 1670?] 19 Apr. 1682”

“William Brattle His Book Cost  ” [A.B. 1680]

” [A.B. 1680]

“Empt. a mag: Brattle. Anno 1683. Guilielmis Williams Liber Cost 6s” [minister at Hatfield; A.B. 1683]

A succession of Williamses follows.

William Camden (1551–1623)

Institutio Graecae Grammatices Compendiaria, in usum regiae scholae Westmonasteriensis. In usum studiosae juventutis adduntur etiam quidam literarum nexus & scripturae compendia quae partim elegantiae, partim brevitatis causa usurpari solent. [Bound with:] Scientiarum Janitrix Grammaticae. London: 1656.

bpl (Prince).

“John Cotton his Gramer 1676” [A.B. 1678]

“Septemb. 25 1677 John Leverett his Booke” [A.B. 1680]

“T. Prince Liber 1701 P 6d” [A.B. 1707]

“William Wharton not ejus Liber”

[Institutio] Graecae Grammatices Rudimenta in usum Scholae Westmonasteriensis. London: 1671.

aas (Mather).

“Crescentius Matherus”

“Cottonus Matherus 1676” [A.B. 1678]

“Nathaniel Matherus 1682” [A.B. 1685]

An abridgment of Camden’s Institutio G. G. Compendaria, also written for Westminster School; of which there is in the hcl a copy of the London, 1695, edition inscribed by William Dudley (A.B. 1704) in 1699, and by William Little (A.B. 1710).

Carminum Proverbialium totius humanae vitae statum breviter deliniantium, loci communes in gratiam iuventutis selecti. London: 1603.

AAS.

“Joseph Belcher His Book 1689” [A.B. 1690]

“Andrew Gardner” [A.B. 1696]

“Nicholas Sever” [A.B. 1701] “Belcher 1701”

“Benjn Gerrish” [A.B. 1733] “Samll Penhallows”

“William Sever of Kingston A.D. 1742” [A.B. 1745]

“Burnet”

“Young men think old men fools but old men know you” Latin verses on a variety of subjects, arranged alphabetically, and to which the second owner has added in ms. Attributed to one S.A.I. by the British Museum Catalogue.

Nathaniel Carpenter (1589–1628?)

Philosophia Libera, in qua adversus huius temporis philosophos, dogmata quaedam nova discutiuntur. Authore Nathanaele Carpentario Exoniensis Collegij. Ed. secunda. Oxford: 1622.

bpl (Prince).

“Thos Brattle His Booke 15 8ber 1673” [A.B. 1676]

“Oliver Noyes” [A.B. 1695]

“Jonathan Remington’s Booke ex dono O.N.” [A.B. 1696]

An attack on Aristotelian philosophy.

Isaac Casaubon. See Bible, Greek N.T.

Marc Casaubon. See Terence

Jean Chatard

[Locutionum Graecarum in Communes Locos per alphabeti ordinem digestarum, volumen.] Paris(?): c 1600.a

aas.

“Edward Rawson” [A.B. 1653]

“Grindall Rawson his book” [A.B. 1678]

The title-page of this volume is missing. What is given above is the subtitle on p. 1. The preface is signed “Johannes Chatardus.” Cf. Catalogue of the Bibliotheque Nationale.

Nathan Chytraeus (Kochhoff)

Carmen Protrepticon, summam doctrinae Christianae complectens. Herborn: 1661. [A Latin hexameter poem, bound with the following:] Viaticum Itineris Extremi, doctrinae et consolationis plenissimum. Additae sunt necessariae quaedam notae per Johan. Piscatorem. Herborn: 1661.

mhs.

“Joseph Webb” [A.B. 1684]

“Nehemiah Walter scripsit Anno Dom: 1682” [A.B. 1684]

Cicero

De Officiis Marci Tullii Ciceronis libri tres. De Amicitia: De Senectute: Paradoxa: & de Somnio Scipionis. London: 1629.a (Plate VI.)

mhs.

“Joseph Eliot His Booke 16[ ]” [A.B. 1656, 1658, or 1681] “John Wompowess His Booke 1665”

“Joseph Browne” [A.B. 1666]

“fungor fruor hetaris affectu letare Joseph Browne [followed by, in another hand] is a fool for writing fungor fruor hetaris affectu letare”

“Jacob Elliots Book 1688 [followed by, in his hand]

This book is mine,

and you may fine

I will drink some wine.

He is very fine

And I will one

I will put you in the pou[nd]”

“Thomas Williams bot at Auction Oct. 1768”

John Wompowess may be a hitherto unrecorded Indian undergraduate. On one of the fly-leaves is a crude sketch of a meetinghouse with the legend “John Savage his meeting house the king of it I say,” probably an allusion to John’s intended vocation.

M. Tulii Ciceronis Orationum pars prima, post Pauli Manutij & aliorum doctiss. correctiones, diligenter emendata. Antwerp: 1567.a

mhs.

“Samuel Eatonus me jure tenet” [A.B. 1649]

“Urianus Oakes hunc librum jure tenet” [A.B. 1649]

“John Williams hunc librum jure emtionis possidet” [A.B. 1683]

“Solomon Williams 1742” [A.B. 1747]

Note by William F. Williams, who gave this book to the mhs, stating that John Williams was the captive minister of Deerfield, and his (W.F.W.’s) great-grandfather.

Orationum Marci Tullii Ciceronis volumen secundum. Editio ad Manutianam & Brutinam conformata. Hanover: 1606.

aas.

“John Cotton his book suae optimo”

“Seaborne Cotton His booke Apr: 9. anno 1646” [A.B. 1651]

“Johannis Cotton [A.B. 1678] est verus possessor hujus libri E D[ono] P[atris] Anno Domini 1673”

Bookplate: “John Cotton his Book Ann. Dom. 1674” [said to be the oldest dated bookplate in the English colonies]

ms. note by J. Wingate Thornton stating that this is one of a set of six volumes of Cicero’s works that descended from John Cotton through his son Seaborn and grandson John to the Reverend Nathaniel Gookin (A.B. 1703), to his son Nathaniel (A.B. 1731), and to the Reverend Jonathan French (A.B. 1771), who gave it to Mr. Thornton.

John Clarke (of Fiskerton, near Lincoln)

Formulae Oratoriae, in usum scholarum concinnatae, cum praxi & usu earundem in epistolis, thematibus, declamationibus contexendis. Editio octava limatior et emendatior. Engraved t.p. London: 1659.

hcl.

“John Barnard Eius Liber” [A.B. 1700]

“John Higginson Tertius 1712/13” [A.B. 1717]

“Pyam Blowers’s Book” [A.B. 1721] “cost 3s 6d”

Another edition. Engraved and colored t.p. London: 1664.

aas (Mather).

“Crescentius Matherus”

“Cotton Mather dedit pater: 1681” [A.B. 1678] on p. 385

“Nathanael Mather” [A.B. 1685]

“Warham” [Mather, A.B. 1685]

“Samuel Mather [A.B. 1723] ex dono ingenii”

Another edition. Engraved t.p. London: 1672.

aas.

“Paulus Dudleius eius liber anno 1688” [A.B. 1690]

Bookplate: “Nicholaus Lynde 1690” [A.B. 1690]

“Joseph Lynde”

Nicholaus Clenardus (Cleynaerts)

Nicolai Clenardi Graecae Linguae Institutiones; cum scholiis et praxi Petri Antesignani [Davenant]. A Frid. Sylburgio denuò recognitae. Hanover: 1617.

hcl.

“L. H[oar]” “Leonard hoar his booke 1651” [A.B. 1650] “Pre. 2s 6d”

“Lege, Intellige, Vive. J. B[rowne, A.B. 1666]” “Pre: 1–6”

Peter Coeleman (Coelemannus)

Opus Prosodicum Graecum Novum. Frankfort: 1651. (Plate VII.)

hcl.

“Joseph Browne anno dom. 1666” [A.B. 1666]

Greek and Latin on opposite pages.

Johannes Amos Comenius (Komenski)

I. A. Comenii Ianua Aurea Linguarum, et auctior et emendatior quam unquain antehac. Autore Teodoro Simonio Holsato. Amsterdam: 1649.b

hcl.

“Joel Jacoomis is my owner” [Indian of Class of 1665]

Described, with facsimiles of Jacoomis’s autograph, in our Publications, xxi. 186, which see for note of eighteenth-century students.

A. Commenii Physicae ad lumen divinum reformatae synopsis. [Quotation from Ludovico Vives.] Amsterdam: 1645.

hcl.

“John Barnard Ejus Liber 1693 . . . His Book Anno D. 1696” [A.B. 1700]

“John Swift” [A.B. 1697]

Described, with facsimiles of the signatures, in our Publications, xxi. 185–186.

Conciones et Orationes ex historicis Latinis excerptae. Argumenta singulis praefixa sunt, quae causam cujusque & summam ex rei gestae occasione explicant. Opus recognitum recensitumque in usum scholarum Hollandiae & Westrisiae ex decreto illustriss. D.D. Ordinum ejusdem Provinciae. Amsterdam: 1648.

aas.

“Crescentius Matherus”

“Increase Mather, 1653” [A.B. 1656]

“Cottonus Matherus”

“S. Matheri, 1741”

Jean Crespin

Τα Σωζομενα των παλαιοτατων, Ποιητων, Γεοργικα, Βουκολικα και Γνωμικα. Vetustissimorum authorum Georgica, Bucolica, & Gnomica poemata quae supersunt. Edidit J. Crispinus. 3 vols, in 1. Geneva: 1639.

aas.

“Hope Atherton his book 1661” [A.B. 1665]

“Nicholaus Lynde” [A.B. 1690]

Latin and Greek on opposite pages. Includes Hesiod’s Works and Days, Theogony, and Shield of Heracles, with annotations by Melanehthon; Theognis of Megara, Phocylides, Pythagoras, Theocritus, Bion, Moschus, selections from the poets of the Middle and New Comedy, and numerous minor poets. The first edition came out in 1570.

Descartes

Renati Des Cartes Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in quibus Dei existentia, & animae humanae a corpore distinctio, demonstrantur. His adjunctae sunt variae objectiones doctorum virorum in istas de Deo & anima demonstrationes; cum responsionibus authoris. Tertia editio. Amsterdam: 1650.

bpl (Prince).

“Samuel Lee tenet Julij 22. die o 1651” “Londini 0:1:0 mr Sam Tomson”

“Daniel Henchman tenet Cantabrigise Aprielis 9, die 1696” [A.B. 1696]

Probably purchased at the sale, in 1693, of the library of Samuel Lee, who arrived in New England in 1686. Cf. our Publications, xxi. 180, and xiv. 143.

Another edition. Amsterdam: 1654.

aas.

“Zech. Brigden me tenet jun 27. 58” [A.B. 1657]

“Samuel Brackenbury. Nec habeo, nec Careo, nec Curo, 1664” [A.B. 1664]

“Dono Dedit D. Generosissimus Mr. Franciscus Willoughby, Lege, Intellige, Vive. J.B.” [Joseph Browne, A.B. 1666] “Pret Lond.[ ]”

Opera Philosophica, editio ultima ab autore recognita. Amsterdam: 1656. hcl.

“Benjamin Lynde me inter suos numerat 10: 1: 1685/6” [A.B. 1686]

“Timothy Lindall His booke 1694” [A.B. 1695]

“Benjamin Wadsworth’s Book 1687 pre. 7s 6d” [A.B. 1690]

A tear on the title-page has defaced an earlier signature than Lynde’s: “Johann . . . Regine” is left.

Includes, with separate title-pages, the Principia Philosophiae, Specimena Philosophiae seu Dissertatio de Methodo; Dioptrice et Meteora ex Galileo translata; Passiones Animae; Meditationes: objectiones et responses.

Jean Despautère (van Pauteren)

Ioan: Despauterii Ninivitae Grammaticae Institutionis lib. VII. Doctè & concinnè in compendium redacti à Sebastiano Duisburgensi. Bound with his Syntaxis and his Artis Versificatoriae Compendium.] Edinburgh: 1660.

hcl.

“E libris Joannis Urie” [A Scottish student]

On page near end: “Isaac Bayly Ejus Liber: 1698” [A.B. 1701]

“Nicholaus Severus Ejus Liber Ex dono I. Bayley August 7 1698” [A.B. 1701]

David Dickson

Therapeutica Sacra, seu, de curandis casibus conscientiae libri tres. London: 1656.

aas (Mather).

“Cottoni Matheri Liber 1681” [A.B. 1678]

A Dictionarie English and Latine: wherein the knots and difficulties of the Latine tongue are untied and resolved, and the elegancies and proprieties thereof fully declared and confirmed by examples. London: 1623.

aas (Mather).

“John Bellingham Eius Liber Anno Dom: 1655” [A.B. 1661]

“Cottonus Matherus 1674” [A.B. 1678]

“Nathanaelis Matheri Liber 1682” [A.B. 1685]

“Samuel Mather’s Book: 1717” [A.B. 1723]

George Downame. See Ramus

Thomas Draxe

Bibliotheca Scholastica Instructissima, or, a treasurie of ancient adagies and sententious proverbes, selected out of the English, Greeke, Latine, French, Italian, and Spanish. Published by Thomas Draxe Batch, in Divinitie. London: 1633.

hcl.

“Elisha Cooke me tenet” [A.B. 1657] “Whiting”

“Joseph Cooke me tenet Anno 1660” [A.B. 1660]

“Mr. Louse had his gutts broake out & fell into Mr. Walkers mouth.” “Old Mr. Louse fell from a book & pitcht into a pecke & broake his neck &c”

Calliepeia, or a rich store-house of proper, choyce, and elegant Latine words and phrases collected (for the most part) out of Tullie’s works, and for the use and benefit of scholars by Thomas Drax. London: 1612.

bpl (Prince).

“Thomas Oakes me jure tenet 1658” [A.B. 1662]

“Thomas Oakes not [in Joseph Taylor’s hand] his booke Anno 1658”

“Joseph Taylor His booke 1665” [A.B. 1669]

“Samuel Sewall his Booke Anno Dom: 1669” [A.B. 1671]

“Stephen Sewall”

“Joseph Sewall His Book”

Another edition. London: 1643.

hcl.

“Elisha Cooke” [A.B. 1657]

“Samuell Johnson”

Another edition (London, 1662) is in the Mather Collection at the aas. It was owned by Increase, Cotton, Nathaniel, Samuel (A.B. 1690), and Samuel (A.B. 1723); also by William Charnock (A.B. 1743). Dates, when given, indicate the use of the book in preparation for college, rather than use in college.

guillaume durand

Rationale Divinorum Officiorum a R.D. Gulielmo Durando Mimatensi Episcopo. Adjectum fuit praeterea aliud Divinorum Officiorum rationale ab Ioanne Beletho theologo Parisiensi. Tomus primus. Antwerp: 1614.

aas (Mather).

“Crescentius Matherus”

“Nathanaelis Matheri Liber 1683. D. dedit Pater” [A.B. 1685]

Erasmus

Epitome Adagiorum Erasmi, Iunii, Cognati, et aliorum παροιμιογράφων. n.p.: apud Guillelmum Laemarium, 1593.

aas (Mather).

“Nathanaelis Mather Liber 1682 [A.B. 1685] D. Dedit Frater suus charissimus, CM.”

A phrase-book. 562 pp. of Erasmus’s, then the “viii centuries” of adages of Hadrian Junius, “in epitomen contractae”; then the proverbs of Johann Alexander Brassicanus, others of Pythagoras, etc.

Institutio Principis Christiani. See Patrizzi

Euclid

The Elements of Geometrie of the most auncient philosopher Euclide of Megara. Faithfully (now first) translated into the Englishe toung, by H. Billingsley. With a very fruitfull praeface made by M. I. Dee. Engraved t.p. London: 1570. (Plate VIII.)

Yale.

“Henrici Dunsteri Liber pret. 1 10 00 bought of Mr Pierce of Newhaven 1652 price thirty shillings.”

See below, Ramus’s Arithmetic and Geometry (1649), also owned by Dunster, and editorial comment thereon. Evidently his translation of this latter work, begun in 1649, was rendered unnecessary by his purchase of the version listed above. Mark Pierce (1597–1656), referred to by Dunster, came to Cambridge from England in 1642, and soon removed to New Haven, where he was schoolmaster and surveyor. He returned to England in 1652 or 1653, and died there.

Eustache de Saint-Paul

Fr. Eustachii a S. Paulo ex congregatione Fuliensi Ordinis Cisterciensis Ethica, sive summa moralis disciplinae. In gratiam studiosae juventutis edita. Cambridge: 1654.

aas.

“Joseph Browne His Booke 1665” [A.B. 1666]

“Lege, Intellige, Vive. J. B.”

Not in the British Museum Catalogue. Fr. Eustache was a French Cistercian who flourished 1610–1635.

Robert Farley

Disputationum Academicarum Formulae per R.F. London: 1638.

aas (Mather).

“Thomas Shepard me tenet. 1651 decemb. 30” [A.B. 1653]

“Samuell Willard his Book” [A.B. 1659] on p. 13

Florus

L. Julii Flori Rerum à Romanis Gestarum libri IV a Johanne Stadio emendati. Editio nova singulis neotericis purgatior & emendatior. Cui accesserunt Chronologicae doctiss: CI. Salmasii excerptiones una cum variis lectionibus. Oxford: 1669.a

hcl.

“Charles Chauncy” [A.B. 1686?]

“steal this Booke if you dare”

M. Fundanus

Phrases Poeticae seu sylvae poeticarum locutionum. Prima vestigia a M. Fundano posita, deinde ab A.S.I.T. auctiores factae. Rotterdam: 1621.b

hcl.

“Elisha Cooke me tenet” [A.B. 1657]

Galileo Galilei. See Gassendi

Petrus Galtruchius

P. Petri Galtruchii Aurelianensis Societ. Jesu, Philosophiae ac Mathematicae Institutio ad usum studiosae iuventutis. Physica Particularis. Caen: 1665.

aas (Mather).

“Cottonus Matherus 1676” [A.B. 1678]

Henry Garthwait

Μουοτέσσαρον. The Evangelicall Harmonie, reducing the foure Evangelists into one continued context. Cambridge: 1634.

mhs.

“Henry Dunster”

“Elizabeth Dunster Her book 1676”

“Benjamin Colmans [A.B. 1692] Book Donum formosse admodum Dominse Elizabethan Wade 1693/4”

Pierre Gassendi

Exercitationes Paradoxicae adversus Aristoteleos. In quibus praecipua totius Peripateticae doctrinae fundamenta excutiuntur. Amsterdam: 1649.

aas (Mather).

“Cottonus Matherus 1675” [A.B. 1678]

“S. Matheri 1740”

Petri Gassendi Institutio Astronomica juxta hypotheses tarn veterum, quam recentiorum. Cui accesserunt Galilei Galilei Nuntius Sidereus, et Johannis Kepleri Dioptrice. Secunda editio. Illustrated. London:1653.

ba.

“Thomas Shepardus me jure tenet 9. 12o. 1675/6 pr 7s 6d” [A.B. 1676]

“Wm Brattle 1705” [A.B. 1680]

“Brenton’s Book 1706” [A.B. 1707]

“William Brown”

“N. Lendall his book Anno D. 1726” [A.B. 1727]

“Old skipper Lendall”

“Was ’ere a man like worthy skipper seen

How foolish is His look, how quere his mein:

How bald and ugly”

“There is a purpose of marriage between Job: Squander-beg & Margaret Hawk-Spun both of Toplifelis alley”

Rudolph Goclenius (1547–1628)

Partitionum Dialecticarum M. Rodolphi Goclenij professoris Academici [Marburgensis]. [Title-page wanting; this is the subtitle, preceded by “Generalia Prolegomena in omnes artes.” Bound with:] Rodolphi Goclenii Praxis Logica ex privatis eius lectionibus, ante aliquot annos excerpta. Frankfort: 1595.

aas (Mather).

“Nathaniel Mather his book 1684” [A.B. 1685]

Thomas Godwyn (1587–1643)

Romanae Historiae Anthologia recognita et aucta. An English exposition of the Roman antiquities, for the use of Abingdon Schoole. Oxford: 1623.a

aas.

“Sr Oakes” “Urianus” [A.B. 1649; AM. 1651]

“William Brattle’s book anno 75 cost 18d” [A.B. 1680]

“John Cotton” [A.B. 1678]

The hcl has a copy of the Oxford, 1628, edition (Plate IX) containing President Dunster’s bookplate, dated March 27, 1634. With it is bound Godwyn’s “Moses and Aaron, civil and ecclesiastical rites used by the ancient Hebrews” (London, 1628), also inscribed by Dunster.

Golius. See Aristotle

Adrian Heereboord

Ἑρμενεια Logica, seu Synopseos Logicae Burgersdicianae explicatio. Accedit ejusdem authoris Praxis Logica. Leyden: 1660.

bpl.

“Thomas Mighell his Booke” [A.B. 1663]

“Thomas Weld his book anno domini 1668: 27 5th month” [A.B. 1671]

“Danforth is admitted into college” [A.B. 1671?]

Another edition. Editio quinta. Amsterdam: 1666.b

hcl.

“Sum Timothei Cutler Cantabrigiensis” [A.B. 1701]

Another edition. Cambridge: 1670.b

bpl (Prince).

“Addington Davenport’s Book” [A.B. 1689]

“Thomas Prince Liber pce 2s 6d” [A.B. 1707]

“Thomas Prince his Book when he was att Colledge harvard.”

Another edition. Cambridge: 1680.

H. A. Larrabee, Esq.

Bound with the London, 1651, edition of Burgersdicius’s Institutionum Logicarum Libri Duo, which see for owners.

Meletemata Philosophica; in quibus pleraeque res metaphysicae ventilantur, tota ethica κατασκολαστικῶς καὶ ἀνασκολαστικῶσ explicatur, universa physica per theoremata & commentaries exponitur, summa rerum logicarum per disputationes traditur. Editio ultima. Accedunt Philosophia Naturalis cum novis commentariis & Pneumatica. Frontispiece portrait of author. Nymwegen: 1665. (Plate X.) aas.

“Simon Bradstreet” [A.B. 1693 or 1700]

“John Legg Boston 1699” [A.B. 1701]

“Libris ex Roberto Gibbs A.D. 1749” [A.B. 1750]

Another edition. Editio nova. Amsterdam: 1680.

hcl.

“Benjamin Colman [A.B. 1692] me suum vocat prid. Cal. Sept. 1690” with variations, on eight or ten different pages.

“Thomas Goodwin his book 1722/3” [A.B. 1725]

“Gulielmus Phipps [A.B. 1728] ejus Liber Ex Dono Honoratisi’ vice Gubernatoris provincise Massachusettensis Domini Spencer Phipps” [A.B. 1703]

“memorandum per me Josiah Quincy ye Day ye 4th of” [A.B. 1728]

“Samuel Danforth” [A.B. 1715 or 1758] “John Swan”

“Artemas Ward Ejus Liber Anno Domini 1746” [A.B. 1748]

Another copy.

aas.

“Thomas Berry hunc librum jure vendicat Anno gratia 1683” [A.B. 1685]. On the back are some lines indicating that it also belonged to his son Thomas Berry (A.B. 1712).

“Adam Cushing His Booke Bought of Monsieure Berry p 12s Anno Dom. 1713” [A.B. 1714]

“Job Cushing His Booke Bought Anno: Domini 1712” [A.B. 1714]

Philosophia Naturalis. T.p. wanting. [Leyden: 1663?].

mhs.

“Nicholas Noyce Ejs Liber 1665” [A.B. 1667]

“Samuel Sewall Samuell Mather” [in Sewall’s hand; both A.B. 1671]

“Thomas Brattle [A.B. 1676] Ejus Liber 15.6.73 statit 2s [changed to] 18d”

“Edvardus Paysonus me suis addidit pret 2s 6d” [A.B. 1677]

“Samuel Moody” [A.B. 1697]

“Mrs. Prudence Chester her Booke”

Johann Ulrich Herlin

Isagoge ad Lectionem Librorum Novi Testamenti per analysin cum versibus μνημονευτικοῖς triplicibus a Johanne-Huldrico Herlino, Collegij Bernensis Inspectore. Bern: 1605.a

mhs.

“Josiah Flynt” [A.B. 1664]

“Henry Flint” [A.B. 1693]

“D. Bradstreet donum Da Nath Clarke”

Hesiod

Ἡσιοδου Ἀσκραίου τὰ εὑρισκόμενα. Hesiodi Ascraei quae extant. Cumnotis ex probatissimis quibusdam authoribus. Opera & studio Cornelii Schrevelii. Leyden: 1653.

bpl (Prince).

“Peter Thacher’s Book May 9th Anno Domini 1692” [A.B. 1696]

Another edition. London: 1659.

bpl (Prince).

“Joseph Flynt”

“Joseph Gerrish his booke 68” [A.B. 1669]

“Attendamus quaeso cum reverencia ad quid dicturi sumus” [in Flynt’s hand]

For an additional Hesiod item, see under Crespin.

Peter Heylyn

Cosmographie in four books. Containing the Chorographie and Historie of the whole World. London: 1657.

hcl.

“John Eliot” [the “Apostle”]

“Si quaerit lector librum quis possidet istum

Nomen subscriptum perlegat ille meum

John Eliot” [A.B. 1685]

“John Eliot sold this booke to Bn Wadsworth [A.B. 1690] July 1692 to Nathaniel Williams 1695” [A.B. 1693]

“Mr. Wadsworth’s Booke 1694”

Fabianus Hippius

Excellentissimi Philosophi M. Fabiani Hippii physici in Academia Lipsensi professori ordinarii problemata physica et logica Peripatetica, in quibus illustriores quaestiones physica & logica inter philosophos veteres & recentiores agitatae. Wittenberg: 1604. John Albree, Esq.

“Nehemiah Walter hunc Librum possidet 1683” [A.B. 1684]