MARCH MEETING, 1894.

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held in the Hall of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences on Wednesday, 21 March, 1894, at three o’clock in the afternoon, Dr. Gould in the chair.

After the record of the last meeting had been read, the Corresponding Secretary read the following letter from the President of the United States: —

Executive Mansion, Washington,

February 22, 1894.

Andrew McFarland Davis, Esq., Corresponding Secretary.

My dear Sir, —I have long delayed my response to your communication informing me of my election to Honorary Membership in The Colonial Society of Massachusetts.

I desire on this day, so suggestive of the patriotic sentiments which it is the purpose of your organization to foster, to express my thanks for the honor conferred upon me by The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, with my sincere wishes for its prosperity and usefulness.

Yours very truly,

Grover Cleveland.

The following-named gentlemen were elected Resident Members: —

|

|

|

|

Mr. Henry E. Woods called attention to the recent organization of an historical society in Groton in this Commonwealth, as follows: —

the groton historical society.

The Groton Historical Society was organized at a meeting held in Groton, 23 January, 1894.

Mr. Woods also stated that the Daughters of the Revolution bad organized a Massachusetts society, and on 25 January, 1894, had adopted a Constitution, from which it appears that the purposes of the organization are in substance those of a topical Historical Society.304 Its objects are: to keep alive the patriotic spirit of the men and women who achieved American Independence; to collect and secure for preservation the manuscript rolls, records, and other documents relating to the war of the American Revolution; to encourage historical research; to promote and assist in the proper celebration of prominent events relating to or connected with the war of the Revolution; to promote social intercourse among its members, and to provide a home for and furnish assistance to such as may be impoverished, when it is in its power to do so.

Mr. Woods further remarked that the Roxbury Military Historical Society has taken active steps towards the better care and preservation of the ancient burial-ground at the junction of Eustis and Washington streets.

Mr. Archibald M. Howe presented the following list of inaccuracies and omissions in the enumeration of Societies in Massachusetts in the list of Historical Societies published by the American Historical Association in 1894: —

inaccuracies.

[Under this heading the correct title is given first.]

- Archæological Institute of America, Massachusetts branch, Boston, instead of

- Archæological Institute of America, Boston.

- Berkshire Historical and Scientific Society, Pittsfield, instead of

- Berkshire Historical Scientific Society, Pittsfield.

- Military Historical Society of Massachusetts, Boston, instead of

- Military Historical Society, Boston.

- Westborough Historical Society, instead of

- Westboro Historical Society.

- Old Residents Historical Association of Lowell, instead of

- Old Residents Historical Society, Lowell.

- Rehoboth Antiquarian Society, Rehoboth, instead of

- Antiquarian Society, Rehoboth.

- Dorchester Antiquarian and Historical Society, Dorchester, instead of

- Dorchester Historical and Antiquarian Society, Dorchester.

- Worcester Society of Antiquity, Worcester, instead of

- Society of Antiquity (T. Dickinson, Librarian), Worcester.

- Winchester Historical and Genealogical Society, Winchester, instead of

- Historical Society, Winchester.

- Bedford Historical Society, Bedford, instead of

- Bedford Historical Society, Boston.

- Lexington Historical Society, Lexington, instead of

- Historical Society, Lexington.305

omitted.

- American Statistical Association, Boston.

- Fitchburg Historical Society, Fitchburg.

- Historical, Natural History, and Library Society of South Natick.

- Malden Historical Society, Malden.

- Medfield Historical Society, Medfield.

- Roxbury Military Historical Society, Boston.

- Wakefield Historical Society, Wakefield.306

place not given.

- Canton Historical Society, Canton.

- Cape Cod Historical Society, Yarmouth.

- Concord Antiquarian Society, Concord.

place inaccurately given.

- Universalist Historical Society, should be Tufts College, instead of College Hill.

improperly included.

- Boston Memorial Association.

questionable.

- American Congregational Association, Boston.

- Ipswich Historical Society, Ipswich.

Mr. Howe observed that the indexes and acknowledgments of gifts in the publications of the Massachusetts Historical Society and of the American Antiquarian Society might be regarded as authorities for the titles of the Historical Societies in Massachusetts. The following errors are therefore worth noting: —

proceedings of the massachusetts historical society, 1876–1877.

- Worcester Society of Antiquaries, probably meant for

- Worcester Society of Antiquity.

Ibid. 1884–1885.

- Historical Society of South Natick, probably meant for

- The Historical, Natural History, and Library Society of South Natick.

Ibid. 1887–1889.

- Berkshire County Historical Society, probably meant for

- Berkshire Historical and Scientific Society.

proceedings of the american antiquarian society, october, 1890.

- Pocumtuck Valley Association, probably meant for

- Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

Dr. Daniel Denison Slade then stated that he was much interested in the history of the gilt cross which is mounted above the entrance to the delivery room of the Library of Harvard University, on the south side of the extension of the east transept of Gore Hall. This cross, he said, was supposed to have been brought back from Louisburg by some member of the Pepperell Expedition, in 1745, and his attention had been attracted to it, not only by the exciting events of this extraordinary expedition, but by the hints which have been handed down to us that there were among the troops some, who, in a spirit of iconoclasm, are said to have equipped themselves with weapons for the destruction of the images in the little church from which the cross was probably taken.307 Dr. Slade then read extracts from Parkman, and from Bourinot,308 and from the Journal of James Gibson,309 illustrative of these points, and added that his interest in the history of this relic had led him to make inquiry among those who might be supposed to be informed concerning it, to ascertain if more facts could be obtained than had already been published in the Memorial History of Boston.310 He had not been able to find the record of the receipt of the relic by the College, but the following note, published in the Library Bulletin in June, 1878,311 contributed some additional information to that given in the sources of authority already mentioned.

“The gilt cross above the entrance of the Library is said to have been brought from Louisburg at the time of its surrender to Sir William Pepperell and the Massachusetts troops in 1745. This date is said to have been painted on it with a further inscription when it was preserved, formerly, among other relics in Harvard Hall; but after the removal of the Library from that building in 1841, these relics were transferred to a building in which the Panorama of Athens was exhibited, and in the fire in which that building was consumed the inscription on the cross was obliterated. It was subsequently placed on the wall in the eastern transept of Gore Hall, and was removed from that position at the time of the recent extension of the transept; and in December last, having been gilded, was placed as now seen.”

Dr. Slade passed round among the members present Volume V. of the “Narrative and Critical History of America,” which contains (on page 436) a reduced fac-simile of a sketch of Louisburg, taken from the original edition of the Journal of James Gibson. He also alluded to a large engraving of Louisburg, a copy of a drawing in the French archives, recently received by the College, in which the church from which the cross is supposed to have been taken, is prominently shown, and closed with a renewed expression of his deep interest in the subject, and an inquiry if any of the members could contribute any information bearing upon it.

Dr. Gould stated that the building which contained the Panorama, and which was burnt in 1845, stood in the rear of Harvard Square, near the church of the First Parish.312 From his father’s house in Roxbury, he saw the fire to which Dr. Slade had referred.

Further discussion was participated in by Mr. Andrew McF. Davis, and Mr. Henry Williams.

Mr. Edmund M. Wheelwright read the following paper:

A FRONTIER FAMILY.313

The Rev. John Wheelwright, the son of a well-to-do Lincolnshire yeoman, was graduated in 1614 at Sydney-Sussex College, Cambridge. Some memory of his prowess in college athletics held to a later time, for Cotton Mather writes that “when Wheelwright was a young spark at the University, he was noted for a more than ordinary stroke at wrestling; and afterwards waiting on Cromwell, with whom he had been contemporary at the University, Cromwell declared to the gentlemen then about him, that ‘he could remember the time when he had been more afraid of meeting Wheelwright at football, than of meeting any army since in the field.’”314

On the second of April, 1623, shortly after the death of the Rev. Thomas Storre, the father of his first wife, and the last incumbent of the living, Wheelwright was presented to the vicarage of Bilsby315 by Robert Welby, the patron. On the eleventh of January, 1632, as the Bishops’ Certificates, and Episcopal Registry of Lincoln, at the Public Records Office, London, show, he was succeeded in the living by Philip De la Mott, upon presentation by the Crown, as the presentation had there escheated “per pravitatem simoniæ.”316 It would appear that Wheelwright had arranged with the patron to resign his living for a sum of money, and that the transaction came to the knowledge of his bishop, who thereupon declared the living forfeited.

The antiquary who found these records holds that in this transaction Wheelwright was guilty of a grave offence, but the gravity of the offence cannot he fairly judged by the standards of to-day. In the early seventeenth century, and at a much later period, a church living was probably regarded as a merchantable freehold, as were commissions in the English army and navy even in our own time. A patron’s right of property in a church benefice seems to have been recognized. At all events, a high authority in ecclesiastical law317 is “not sure that a simoniacal contract to present as patron would vacate the benefice.” If patrons of livings could sell them without punishment, the clergymen who bought or who sold what they bought would not be held by public opinion guilty of “grave offence” in violating the law against simony. A law which only carried a penalty to one party to such a transaction, where the moral obligation equally applied to both parties, was so unfair that it would naturally become a dead letter. By such a law, however, a bishop could easily rid his diocese of a clergyman not to his liking, — a troublesome nonconformist, for instance.

Apparently, Wheelwright’s simoniacal act did not injure his personal reputation. Brook in his Lives of the Puritans says “he was much esteemed among serious Christians.” Hanserd Knollys318 sought Wheelwright out, after 1632, for religious conference and instruction. Later, when Wheelwright’s New England enemies tried in every way to break his influence and to justify their treatment of him, there was no intimation of any cloud on his past career. Indeed, Cotton Mather in this connection says that “his worst enemies never looked on him as chargeable with the least ill practices; he was a gentleman of the most unspotted morals imaginable; a man of most unblemished reputation.”319

Shortly after losing his benefice, Wheelwright is supposed to have lived at Anderby, Lincolnshire, where he had relatives, and also at Laceby, in the same county, where one of his children was born.

His first wife having died in 1630, he married Mary Hutchinson. In 1636, Wheelwright, with his family and Mrs. Hutchinson, his mother-in-law, emigrated to Boston. With him came his brother-in-law Augustine Storre and his family. Wheelwright was well received in the Colony. An unsuccessful attempt was made by his friends to associate him with Cotton in the Boston Church; later, he was made pastor at Mt. Wollaston of “a new church to be gathered there.” All things looked promising for a useful and happy life in his new home.

However, being a man of a contentious disposition, Wheelwright, with his sister-in-law Anne Hutchinson and Henry Vane, then Governor of the Colony, was soon in hot controversy320 with the conservative party, the question at issue being that of the “Covenant of Grace” vs. the “Covenant of Works.” The strange verbiage used in this dispute carries little meaning to us to-day, yet, in spite of all the theological hair-splitting, we can understand that the party Wheelwright so stoutly defended stood for freedom of speech and opinion, and for a more liberal theology than that held by the majority of the Puritans. “I will petition to be chosen the universal idiot of the world,” said the Rev. Mr. Ward of Ipswich, “if all the wits under the heavens can lay their heads together and find an assertion worse than this, — that men ought to have liberty of conscience, and that it is persecution to debar them of it.”

The priestly antagonism to free discussion is shown by the Rev. Mr. Welde’s lament: “But the last and worst of all, which most suddenly diffused the venom of these opinions into the very veins and vitals of the people, was Mistress Hutchinson’s double weekly lecture.”

There was not a little political partisanship mixed with these theological disputes. The controversy between Wheelwright and the conservative clergymen was the principal issue in the canvass of Winthrop as the candidate for Governor of the conservative party against Vane, who was a candidate for a second term. Winthrop was elected.

At the expiration of his term of office, Vane left the Colony in disgust. Evil days then fell on Vane’s friends; his enemies lost no time in crushing out the liberal ideas he had encouraged. Previous to Winthrop’s election, Wheelwright had been found guilty by the General Court of “sedition and contempt of the Civil Authorities,” a charge based on his metaphorical use of the word “swords” in his Fast Day sermon. This sentence was passed after a two days’ contest, when, writes William Coddington, “the priests got two of the magistrates on their side and so got the major part of them.”

After Winthrop’s election, sentence was passed on Wheelwright as follows: —

“Mr. John Wheelwright being formerly convicted of contempt and sedition and now justifying himself and his former practice, being to the disturbance of the civil peace he is by the court disfranchised and banished our jurisdiction and to be put in safe custody except he should give sufficient security to depart before the end of March.”

Wheelwright appealed “to the King’s majesty.” The Court replied that “they had full jurisdiction as expressed in their Charter.” Wheelwright, having refused to give security “for his quiet departure,” was placed in the marshal’s custody. The next day he was released “upon his promise that if he were not departed within fourteen days he would render himself at the house of Mr. Stoughton … there to abide as a prisoner.”

Although during the controversy there had been at no time fear of an armed revolt in opposition to the tyranny of the conservatives, all those who had signed a remonstrance against the treatment of Wheelwright were deprived of “guns, swords, pistols, powder, shot, & match,” and some of the leaders of the liberal party were banished. Many of the Colony’s best citizens were cut off from all active service in its public affairs. Some cause for rigorous action was not lacking. The Boston followers of Wheelwright had refused to serve in the Pequot War because their minister, who was to be their chaplain, was “under a Covenant of Works,” — an act of distinct insubordination.

In the short notice given him, Wheelwright disposed of his Mt. Wollaston lands at a loss. He left Massachusetts in November, 1637, tarried awhile just beyond the “bound-house” near Hampton; then pushed his way, through the heavy snows of that bitter winter, to the falls of the Squamscot on the Piscataqua. In the early spring he was joined by his wife and family, and by Augustine Storre, John Compton, and Nicholas Needham. These pioneers purchased from the local Sagamores a large tract of land and founded Exeter.

A little later William Wentworth, Edward Rishworth, Samuel Hutchinson, Edmund Littlefield, Philemon Pormortt, and twenty other heads of families joined the colony. All were either Lincolnshire friends321 of Wheelwright or residents of Boston and its neighborhood, who had supported him in his controversy with the colonial hierarchy.

In July, 1637, when the Antinomian controversy was at its height, several Lincolnshire families arrived in Boston. They were attracted to Massachusetts, where Anne Hutchinson, Vane, Wheelwright, Coddington, and Cotton, all Lincolnshire people, were prominent. The government gave these men permission to tarry within its borders but four months. Prompt arrangements had to be made by them for an abiding place. As they were forced to leave the Colony at about the time of Wheelwright’s banishment, it is probable that those who did not go to Rhode Island had found winter quarters along the Piscataqua.

The first year at Exeter was a busy one. The colony was harmonious without any formal government. The next year the population was doubled. Settlers of different antecedents and purposes joined the colony. As it was found necessary to have some form of government, the “Exeter Combination,”322 a document evidently drawn up by Wheelwright, was subscribed to by the colonists. One Gabriel Fish was arrested for “speaking against his Majesty.” Finally, the terms of the constitution not justifying the punishment of this contemner of royalty, he was released from custody; but the Combination was so amended that its protestations of loyalty to the Crown satisfied the most ardent royalist;323 shortly afterwards a special law was passed that made “reviling his Majesty, the Lord’s anointed,” a capital offence.

Traffic was allowed with the Indians in all things save “powder, shot, or any warlike weapons, sack or other Strong Watters.” A church was established, of which Wheelwright was the pastor.

This little Republic prospered; its independent government, however, had a short life. Against the protest of the people of Exeter, the Bay Colony planted a settlement at Hampton, territory included in the Indian purchase of Wheelwright and his associates. Exeter’s protest was met by the Baymen with the counter-claim that Exeter was within the patent of their Colony. After all the other New Hampshire plantations had acknowledged the sway of Massachusetts, in May, 1643, twenty-two Exeter settlers, but one of whom, Anthony Stanyan, was an immediate follower of Wheelwright, petitioned the General Court for annexation. The petition was granted, and Exeter came under the rule of the Bay Colony. Wheelwright and his proscribed friends were not unprepared for this turn in affairs. Two years previously, Hutchinson and Needham had arranged terms with Thomas Gorges, allowing them to take up land and build at Wells, Maine. Availing themselves of this right, these two, with Wheelwright, Storre, Wentworth, Littlefield, Rishworth, Pormortt, and six other Exeter associates, moved to the coast of Maine. By a later agreement with Gorges, Wheelwright, Rishworth, and Henry Boade, who had settled earlier at Saco, but moved at this time to Wells, were appointed a commission authorized to allot lands and to make grants to fit persons, under certain conditions, subject to Gorges’s veto. Wheelwright bought four hundred acres of land on the easterly side of Ogunquit River.324 He built a small one story house and a saw-mill at the “Town’s End.” He was, of course, the pastor of the church gathered at Wells by the Exeter Associates.

In 1607, the Plymouth Company sent out two colonies, one to Jamestown and one to the coast of Maine under Popham, with Raleigh Gilbert, the son of Sir Humphrey, as lieutenant. The Maine colony was short-lived. Later, under direct grants from the Plymouth Company, and under grants from Sir Ferdinando Gorges, settlers spread along the shore from the Piscataqua to Sagadahoc. This colony, known at first as “New Somersetshire,” was peopled as was the colony of Virginia. Many “gentlemen adventurers,” among them several younger sons of good family, sought the Maine coast as planters, traders, and for the fisheries.325 Robert Gorges,326 the son of Sir Ferdinando, came over as Governor of his father’s Province, but remained only for a short time. His cousins, Thomas and William Gorges, were longer in the Province as the patentee’s agents. At Kittery, was Francis Champernowne,327 of the best Devonshire stock, kin of Sir Walter Raleigh and Sir Humphrey Gilbert, and a connection of the Gorgeses and the Pophams; at Blackpoint, Henry Jocelyn,328 of an old Hertfordshire family, and with him his friend Capt. Thomas Camock,329 a nephew of Thomas Rich, the first Earl of Warwick of that name; at Saco, Henry Boade,330 of the Hampshire gentry; at Winter Harbor, Joseph Bolles,331 an “armiger” of Nottinghamshire; at Agamenticus, Edward Godfrey,332 upon whose father’s monument in the Church of Wilmington, Kent, were carved the arms of Godfrey de Bouillon.

The bulk of the population was made up of colonists sent over by the Gorgeses, possibly not of such wretched material as Popham’s colony, but certainly not of the self-reliant and earnest character of the bulk of the Plymouth and Bay colonists. Here too were waifs, strays, and adventurers, rude in manners and loose in morals, who had drifted thither from the westward colonies and from across the ocean. The government of New Somersetshire was lax, and there is not a little evidence of a demoralized society. The colonists of this province, with many of the first settlers of New Hampshire, were for the most part from the south and west of England, not from the counties whence came the Puritan emigration, — they were not Puritans. To say the least, they had little community of feeling or interest with their neighbors of the Bay and Plymouth colonies.

Until, and even after the Revolution,333 among the people dwelling immediately about the mouth of the Piscataqua and in the Province of Maine, society had an aristocratic basis. The manner of life and the large proprietorship of Sir William Pepperell is an example of this tendency. Two forces, the climate, and the prox. imity of the Bay Puritans, worked against the development of an aristocratic society. The severity of the climate prevented the advantageous employment of many slaves; aided by the conditions of the climate and soil, the iron hand of the Bay hierarchy slowly but surely moulded gentle and common into a community of almost uniform sentiment and action. The Puritanism of the Bay, with its subtle hostility to royal power, unconsciously levelled the people into a democracy.

Wheelwright and his followers found among the settlers who had preceded them in the settlement of Wells, few, if any, gentlemen; Boade, as noted above, and Bolles joined the community on the coming of the Exeter Associates. The early inhabitants of Wells were for the most part “poor whites,” not at all the stuff to suffer martyrdom “for freedom to worship God.”

The Exeter Associates had qualities much needed in the unevenly balanced community of New Somersetshire. Immediately becoming the controlling force at Wells, they and their descendants were its recognized leaders in war and peace for one hundred and fifty years.

There was little charm and great hardship in the life at Wells. All the Exeter company of the first generation, except Edmund Littlefield, sooner or later sought homes elsewhere. Wentworth went to Dover; Hutchinson and Needham removed, probably, to Boston; Augustine Storre may have returned to England. His son, William, settled at Dover and it was possibly he who is found a little later at Ipswich. It is supposed that Joseph Storer,334 who remained at Wells, was a kinsman of Augustine Storre. Rishworth moved to York.

In October, 1643, shortly after the murder of Anne Hutchinson by Indians, Wheelwright wrote Governor Winthrop seeking pardon of the Bay Colony in terms which would make him appear a recanter of his convictions and a self-abasing apologist, if it were not that a supplementary letter to Winthrop of quite different tenor has been preserved. In the first letter he says that it then appeared to him that the cause for which he had contended was “not of that nature and consequence as was then presented to me under the false glare of Satan’s temptations and mine own distempered passions,” that he had “done very sinfully” and humbly craved the pardon of the State. It is evident that he did not expect that his words would be taken literally but rather in the sense that he was a “poor miserable sinner;” for on receiving answer from Winthrop, he hastened in reply to qualify his first letter and to explain his attitude more specifically. He asserted that he could not, “with a good conscience,” condemn himself “for such capital crimes, dangerous revelations, and gross errors” as had been charged against him; that he was willing to admit his faults, but demanded opportunity to make just defence against charges of which he deemed himself innocent; that he did not come to the court as a suitor begging mercy upon his “confession,” but to ask justice upon his “apology and lawful defence.” The second letter is thoroughly straightforward and explicit; none the less it was ignored by the General Court in the vote passed 9 May, 1644, —

“that Mr. Wheelwright (upon p̃ticular, solemne and serious acknowledgement & confession by letter, of his evill carriages & of ye Crts justice upon him for them) hath his banishmt taken offe, & is received in as a member of this com̃onwealth.”

In 1647, Wheelwright accepted a call to be the assistant of the Rev. Mr. Dalton at the church at Hampton. With those who went with him from Wells, and those already settled at Hampton, eleven heads of families of the Exeter Colony made their homes at the latter place. Samuel Wheelwright, a boy of twelve, the son by the second wife, Mary Hutchinson, went with his father to Hampton.

In 1657 or 1656, Wheelwright made a voyage to England, not at first severing his connection with the Hampton church. He remained in England six years; probably, but for the downfall of the Puritan party, he would not have returned to New England. In a letter335 to his parishioners at Hampton, bearing date 20 April, 1658, he says: —

“I have lately been at London about five weeks. My Lord Protector was pleased to send one of his guard for me, with whom [Cromwell] I had discourse in private for about an hour. All his speeches seemed to me very orthodox and gracious; no way favoring sectaries. He spake very experimentally to my appreciation of the work of God’s grace, and knowing what opposition I met withal from some whom I shall not name, exhorted me to perseverance in these words, as I remember: ‘Mr. Wheelright, stand fast in the Lord and you shall see that these notions will vanish into nothing;’ or to that effect. Many men, especially the sectaries, exclaim against him with open mouths, but I hope he is a gracious man. I saw the Lord Mayor and Sheriff with their officers carry sundry fifth monarchy men to prison, as Mr. Can, Mr. Day, with others who used to meet together in Coleman street to preach and pray against the Lord Protector and the present power.”

As to the “opposition,” these fifth monarchy men “met withal,” Wheelwright made no comment.

Hutchinson says that Cromwell, then on bad terms with Vane, was probably dissembling in the courtesy be showed Wheelwright, as he must have known of the friendship of Vane and Wheelwright. There would seem to be ground for the doubt of Cromwell’s sincerity in this instance, as he had earlier applauded the Colony for “‘banishing the evil seducers which had risen up among them,’ of whom Mr. Wheelwright and Mrs. Hutchinson were chief.” However, the consideration shown him won Wheelwright over to the Protector’s interest, and yet his friendly relations with Cromwell did not break his friendship with Vane. Hutchinson records that Wheelwright “lived in the neighborhood of Sr Henry Vane,336 who had been his patron in New England, and now took great notice of him.” Wheelwright’s relations with Cromwell are generally understood to have proved of service to the Colony; we find in 1658 certain people of Wells and neighboring towns in a petition to the Lord Protector to confirm the jurisdiction of Massachusetts over them, referring to “their pyous and reverend friend, Mr. John Wheelwright, sometime of us, now of England,” for information concerning their character and condition.

It has been suggested that the existence of Wheelwright’s supposed portrait in the Massachusetts State House, is connected with the recognition by the Colony of his services at court.337

After Vane’s execution, Wheelwright returned to Massachusetts. He was pastor at Salisbury, where he died, being the oldest clergyman in the Colony, 15 November, 1679, aged 87. In his will he bequeathed his land at Wells and lands at Mumby, Minge, and Crofft, in “oulde England,” to his children and grandchildren. He had, in 1677, conveyed an estate at Mawthorpe, Lincolnshire, to Richard Crispe, in consideration of his marriage to his youngest daughter, Sarah. He left his “bookes” to his son Samuel, and to his “latter wife’s children all my plate to be equally divided amongst them by two indifferent parties chosen by themselves.”

Cotton Mather, who did not sympathize with Wheelwright’s religious views, for which, however, he thought him to have been “persecuted with too much violence,” says of him, “He had the root of matter in him.” This root had sprouts, which, if Mather had recognized them, he would have exerted himself strenuously to lop off. Charles Francis Adams says: —

“The seed sown by Wheelwright in 1637 bore its fruit in the great New England protest of two centuries later, when, under the lead of Channing, the descendants in the seventh generation of those who listened to the first pastor at the Mount, broke away finally and forever from the religious tenets of the Puritans.”

To return to the settlement at Wells: Alexander Rigby, a gentleman of high influence in the Puritan party, had purchased the “Plough Patent,” one of the careless grants of the Plymouth Company which overlapped territory included in Gorges’s patent. Parliament confirmed Rigby’s rights to the exclusion of Gorges, a Royalist. Gorges died in 1647. His heirs took no steps to govern what remained to them of their province, whose people, those of Piscataqua, Gorgeana (York) and Wells formed a “Combination” to govern themselves in accordance with “the law of their native country.” On this basis Edward Godfrey was chosen Governor of the province of Maine. This loose government continued until 1652, when the Bay Colony bestirred themselves to govern the whole Province. From this time on, for several years, there was a partisan struggle between the compact organization of the Bay Colony and the unassimilated people of the Province. Massachusetts claimed jurisdiction under its Charter. The people of the Province unsuccessfully appealed to Parliament that “they and their posterity might enjoy the immunities and privileges of freeborn Englishmen.” In 1653, the Colony appointed Commissioners to regulate the affairs of the Province. There was, except at Wells, general acquiescence in the authority of the Bay Colony.

Thomas Wheelwright, son of John, by his first wife, was permanently settled at Wells.338 He was an active supporter of the Bay Colony in its contest with the Gorges family for jurisdiction in Maine; in 1652 he swore allegiance, as a freeman, to Massachusetts; the following year he was appointed magistrate at Wells. At this time Massachusetts was making strenuous efforts for the submission of the people of Wells, a majority of whom did not take kindly to the rule of the “Baymen.”

Thomas Wheelwright, with others, of whom some, as Boade and Rishworth, were later of the Gorges party, petitioned the Lord Protector “for government under ye colony of ye Mass.” They asserted that the Gorges party were for the most part “professed Royalists;” that “changing may throw us back into our former estate to live under negligent masters, ye danger of a confused anarchy as may make us a fit shelter for the worst of men, delinquents, and ill-affected persons.” Under the rule of Gorges, Maine had suffered not a little by people of the kind described in this petition, still many of the better sort, although they had been forced to sign the submission of 1653, opposed the jurisdiction of Massachusetts. It is evident that the Maine people preferred lawless neighbors to the tyranny of the Baymen. Indeed, of the Exeter Associates and their sons, Thomas Wheelwright and Nicholas Cole alone consistently supported the Bay party in this controversy. Samuel Wheelwright, who returned to Wells to occupy the two hundred acres his father deeded to him before his voyage to England, did not join the political party his half-brother supported. Although the General Court exempted the people of Maine from the law of Massachusetts requiring freemen to be church-members, it did not absolve its people from the severe enactments repressing freedom of opinion. The court records show numerous prosecutions under these acts. In these political contests no small part of the opposition to the Bay Colony was due to the fear of its religious tyranny, and to this tyranny may be ascribed the later defections in Maine from the Bay party. It would appear that the “Antinomians” had more sympathy with the Church of England than with the Puritanism of the Bay; at all events, Episcopalians and Antinomians were on close terms of intimacy. Wheelwright and his associates, when forced to leave Exeter, sought asylum under a grant from Gorges. There were very friendly relations between Vane and Samuel Maverick, an Episcopalian, a sympathizer with the Gorgeses, an owner of land at Agamenticus, and in 1665 one of the King’s Commissioners appointed in the Gorges interest. Maverick’s son married a daughter of John Wheelwright. Anthony Checkley, Maverick’s friend, married another. Edward Lyde, one of the first wardens of the Episcopal church in Boston, married a third daughter. Edward Rishworth, son of one of the principal opponents of the Colony, married a fourth. The Littlefields, Pormortt, and Boade, avowed their loyalty to the Church of England. William Wardell, of the former Exeter Company, was violent in denouncing the religion of the Bay Colony; he and William Cole were strenuous in their opposition to its aggressions.

After the submission of 1653, the Bay Commissioners took under consideration the church John Wheelwright had founded at Wells. It had, at this time, but four members, Pormortt, Warded, Boade, and Francis Littlefield. Pormortt and Boade, at their own request, were dismissed; the church was then dissolved, an act without precedent, except the dissolution of the “Chapel of Ease” at Mount Wollaston. Conservative Puritanism thus crushed out the sole remaining organization of the more liberal Puritans.

Godfrey went to England to press Gorges’s claim. As a result, in 1661, a committee of Parliament reported in favor of the patentee. The next year, Gorges appointed a council of twelve to govern the Province, among them Jocelyn, Rishworth, Bolles, and Champernowne. Wells refused to send representatives to the General Court. The following year some of the towns of the Province submitted to the Colony. Wells still held aloof. The “engrasping colony,” as Godfrey aptly calls it, then took rigorous steps to assert its authority; through its commissioners it appointed its own magistrates. There were many political persecutions: for instance, James Wiggin was sentenced to fifteen lashes on his naked back for saying, “with an oath,” when asked if he would carry a dish of meat to the Bay Magistrates, “if it were poison he would carry it them.”

Charles II. now gave his support to the Gorges claim. In 1665 the King’s Commissioners339 appointed twelve magistrates to govern the Province; among them were Jocelyn, Champernowne, Rishworth, and Samuel Wheelwright. Each party in this contest had its separate government, each denying the authority of the other, each instituting against the other legal proceedings which seem to have been, in part, political persecutions.340

Early in July, 1666, the Bay Colony, finding itself thwarted by the King’s justices, sent commissioners341 to York, supported by a body of foot and horse, authorized to arrest and bring to trial all persons presuming to exercise authority not given by the Colony.

The Bay Commissioners went to the meeting-house, where they ordered the towns that had not then recognized the authority of the Colony to make returns for associates and jurymen. The King’s justices forbade the making of such returns; they presented the Commissioners with the royal warrants of their authority; these the Bay men refused to have read until they had finished their work; that afternoon they finished it, taking a leaf out of the book of the Lord Protector. Delegates from the towns, summoned by the King’s justices, convened at the meeting-house; at the convention appeared the Massachusetts Commissioners, headed by their marshal, and, we may suppose, supported by their halberdiers, and backed by grim pikemen of the Bay. They found their way through, and addressed the exasperated assembly. After a stormy debate the Bay men, in the language of the caucus, “held the rail.” With sturdy courage they declared, —

“we have been sent to settle the peace of the Province, and God willing, we mean to finish up what we have begun. We know that the King’s Commissioners have charged Massachusetts with treachery and threatened her with the vengeance of the King, but by divine assistance we have the power and we mean to exercise it.”

They did so, declaring the election of five associates, and among other appointments making two of the Littlefields, recent converts to their party, respectively, Lieutenant and Ensign at Wells.

After this, the first overt act of the Bay Colony distinctly contemning royal authority, the power of the King’s government in the Province gradually waned. On the other hand, having gained its point, the Colony does not appear to have been active in enforcing the laws in the territory it had seized, or perhaps, on account of some outbreak among its opponents, it sought to discipline the people by the temporary withdrawal of its authority. In 1668, Thomas Wheelwright writes as follows: —

“Worshipful Mr. Bellingham, — My humble service presented unto you. By the importunity of some of our neighbors, that the town of Wells is in a sad condition for lack of good government, which they had hoped they should here have enjoyed; but their hopes so defeated that it made their heart sick. Their humble desire is, that you would hasten.”

The Littlefields, with others formerly of the Gorges party, petitioned the General Court, “that our care be taken under your tuition and government, that so your honorable care of justice may be executed among us as formerly;” prefacing their petition by the statement that they had been deprived of the benefits of the Colony’s government, “by some among us who had been ill affected to your government,” explaining that the petitioners, “in revolting and turning from our former obedience,” had been led astray largely by the influence of Edward Rishworth.

There was much anger at this desertion. Several men, unwilling to abide the rule of Massachusetts, left the Province. Even with so many gone over to the Bay party, and its opponents weakened by emigration, Wells for some years persistently refused to send representatives to the General Court.

The opposition to the rule of Massachusetts gradually died away. Organized power near at hand superseded power with no force at its command, delegated from across the ocean to individuals.

In 1670, Samuel Wheelwright appears to have accepted the inevitable, and to have been in good standing with the Colony; he was then chosen one of the selectmen of Wells. In 1675, apparently at the time of threatened uprising against the authority of Massachusetts, Lieut. John Littlefield was ordered by the General Court to exercise his authority in putting down disturbances that might arise, after consulting with Samuel Wheelwright and William Sayer.

In 1676, a vote was passed in town meeting, authorizing Samuel Wheelwright, William Symonds,342 and John Littlefield to petition the King “for future settlement under the Bay Government.”

On summons from the King, dated 10 March, 1675–6, Massachusetts sent agents to England; its Charter was not annulled, but the right of soil and government of Sir Ferdinando Gorges was confirmed. Thereupon, in March, 1677, the Colony checkmated the King by purchasing from the later Ferdinando Gorges, his rights in the Province. A protest was made by certain of the Maine people. Massachusetts sent troops into the Province and proclaimed her right to govern under the Gorges purchase.343 In 1681, inasmuch as the Provincial Council instituted by Massachusetts met at Wells, it became the capital of the Province. In spite of the general acceptance of the Colony’s rule, from time to time the old rancor showed itself. John Bonython was indicted “for contempt of Massachusetts authority, and for the saying that the Baymen were Rogues, and that Rogue, Major Leverett, he hoped, will be hanged.”

Whatever the rights of the Gorgeses, whatever the faults of the Bay Colony, the people of Maine soon found that they had done well in securing the support of a strongly constituted government within quick call. Governed as they had been under the Gorgeses, the settlement would, undoubtedly, have been destroyed in the Indian wars from which it was now to suffer, intermittently, for seventy years.

When King Philip’s War broke out, panic seized the people of Wells. The Council, sitting at Boston, 9 December, 1675, —

“taking into their Consideration the prsent state of the Towne of wells in respect of the vnsetled frame of the Inhabitants there in this Tyme of Dainger … Ordered And Appointed that the Lieften͞nt Jno Litlefeild doe Effectually Apply himself to Comand in cheife all that are Capable of bearing Armes in yt Towne & to order them in the best manner yt may be for their mutuall safety.… [and] Consult wth mr Samuel whelewright & mr wm Symonds.… [These three men are made a committee] to Impresse all such persons, prouission, Ammunition or otherthing wthin their owne Towne as shall be necessary & cannot otherwise be had. And … all persons … there doe in no case desert the place … vpon penalty of being liable to forfeit all their estates & interests in yt towne.”344

Several attacks were made on the town, and many individuals were killed or captured, and at the close of King Philip’s War the people of Wells, with horses, cattle, and crops destroyed, were in worse estate than they were under the hard conditions of the first settlement. In the eleven years’ respite from Indian raids that followed, they made good the ravages of the past and took precautions for the next war. The town was protected by three garrison houses. Samuel Wheelwright had one at the “Town’s End;” his son, John, had another palisaded house. This foresight was to be repaid. Wells was recognized by the enemy as the stronghold of the Province. They had planned to make great efforts for its destruction.

The next war came suddenly. 23 January, 1689, Samuel and John Wheelwright and Joseph Storer sent this excited letter to Major Frost, the commander of the colonial forces in Maine: —

“These are to inform you that Lieut. Fletcher came to Wells and brought two wounded men to Wells and the Indians has killed yesterday eight or nine men at Saco, (who were looking for horses to go along after the Indians, but now are disappointed and cut off,) and they judge there are sixty or seventy Indians that fought the English and they have burnt several houses and destroyed a deal of their corn, and we judge now is the time to send some of the army east to Saco. The people are not able to bury their dead without help; and this day just as they came away, they heard several guns go off, and know not what mischief is done. Pray give York notice forthwith.”

The Baron de St. Castin, with his red brothers-in-law, was on the war-path. The garrison houses at Wells were filled with refugees from the eastward. No attack was made that year. St. Castin was held in check.

In May, 1690, Samuel Wheelwright, Joseph Storer, and Jonathan Hammond sent to Major Frost this despatch: —

“These are to inform you that the Indians and French have taken Casco Fort and to be feared that all the people are killed and taken. Therefore we desire your company here with us to put us in a posture of defence, for we are in a very shattered condition — some are for removing, some are for staying; so that we stand in great need of your assistance.”

Later, the same men, with John Wheelwright, sent a despatch to Boston urging relief, saying: “The enemy is now very near us. Saco is this day on fire. We expect them upon us in a few hours or days at least.” Major Frost wrote on the same date: “All Falmouth is certainly destroyed, and not one alive hut what is in the enemy’s hands.” He goes on to report that the scouting vessels saw —

“Black Point, Spurwink, and Richmond’s Island burning, so that nothing now remains eastward of Wells. There are 3 or 400 women and children come in from the eastward this week who will perish unless assisted of the charity of others. Wells will desert if not forthwith reinforced.”

The Commonwealth sent a strong force to the eastward. St. Castin was still kept at bay. The Indians, however, made in the spring or summer an attempt on Wells, in which two men were killed, one taken captive, and several houses burned.

Wells was now the absolute frontier. Captain Andrews, then in command, wrote to the Council in October, 1690: —

“I crave of your honors that if soldiers must be kept here that we may be relieved and others sent in our room, for there is such animosity between the soldiers and the inhabitants that there is little hopes of us doing anything that tends to God, honor, or the good of the country.”

He complained that the people were on the point of leaving the garrison for their own houses; that they would subject themselves to no discipline; “that if the enemy comes upon us I am afraid their carelessness will be both their destruction and ours also.”

The great number of refugees at Wells was a severe tax on its people. In spite of repeated appeals the government sent no provisions for their maintenance. Major Benjamin Church exerted himself to obtain assistance for the destitute. On this errand he went to Rhode Island and to Plymouth. A collection was taken up in the churches of Massachusetts and Connecticut, and forwarded to John Wheelwright, John Littlefield, and Joseph Storer, “to be appropriated as they judged necessary for the several garrisons.” The militia of York and Wells were “empowered to impress and take any fat cattle, especially from such persons as desert the Province, they giving a true account of the cattle they shall take.” Systematic preparations were made for war. The several garrisons were grouped into three commands under Samuel Wheelwright, Joseph Storer, and John Littlefield. Each was ordered to keep a constant patrol. The government did not seem to appreciate the exigency. 25 May, 1691, the Wheelwrights, Storer, and Hammond wrote to the Council, urging the need of assistance. Thirty-five men of Essex were sent to Wells in June, under the command of Captain Convers, the officer requested by the men of Wells. They came in the nick of time; half an hour after their arrival at Storer’s garrison house, an attack was made by Moxus and his band. Of this attack Governor Sloughter of New York writes: “The Eastward Indians and some French have made an assault upon ye garrisons in and neere the town of Wells and have killed about six persons thereabout. They drove their cattle together and killed them before their faces.” The siege lasted four days; then, discouraged by the resistance of the garrison, the savages retired, Madockanando crying out, “Moxus miss it this time; next year I’ll have the dog Convers out of his den.”

After the raid in July, 1691, George Burroughs, John Wheelwright, and other leaders at Wells wrote to the government “for men with provisions and ammunition for strengthening of our town,… also that there be an effectual care taken that the inhabitants of this province may not quit their places without liberty first obtained from legal authority.” Again, in September of the same year, they petitioned for soldiers and supplies.

Early in June, 1693, but fifteen soldiers garrisoned Wells. A reinforcement of thirteen men with supplies arrived by sea. Before a landing could be made “the cattel came frightened and bleeding out of the woods,” and gave warning of the approach of the enemy. Fifteen of the townsmen rallied to reinforce the soldiers at Storer’s garrison house. Five hundred Indians and Canadians led by French officers beleaguered the garrison house and the vessels, and contrary to their custom fought in the open.345 The fighting lasted three days, when the enemy withdrew having lost several of their number, among them their commander, La Broquerie, who was killed in the attempts to extricate from the mud a huge shield on wheels which his men were pushing towards the stranded sloops. This defence of Wells was, in the words of Mather, “an action as worthy to be related as, perhaps, any that occurs in our story.”

After this foray, the garrison was greatly strengthened. Though individuals were killed in the town or neighborhood, among them Major Charles Frost, who was waylaid on his return from meeting, no concerted attack was made on the town for several years. Major March succeeded to Major Frost’s command and was stationed at Wells with the ample force of five hundred men.

In such times, the owners of garrison houses were perforce inn-holders. There was relatively a greater rush of guests, and certainly a longer season for these frontier Bonifaces than now favors the Maine coast during a “hot wave.”

Wheelwright, Storer, and Littlefield were inn-holders licensed to sell liquor. Byron says: —

“There’s naught, no doubt, so much the spirit calms,

As rum and true religion.”

This satire well applies to the early New Englanders. There was much hard drinking at Wells, as elsewhere in the colonies. It was customary to serve jurors rations of liquors; judges were not infrequently indicted for drunkenness.

Games of all sorts were forbidden. John Wheelwright and Joseph Storer were indicted for “keeping keeles and bowles at their houses contrary to law.” This was in the dark days of 1692, when time fell heavy on the hands of men cooped within the palisades.

At this time, the Rev. George Burroughs,346 the minister at Wells, was arrested, and executed, on the charge of witchcraft. After his arrest, we find Samuel Wheelwright with others petitioning the Governor and Council, as not only being “objects of pity with reference to the enemy and the length of the war, but also with reference to their spiritual concerns, there not being one minister of the Gospel in these parts; and in this town of Wells there are about forty soldiers and no chaplain, which does much dissatisfy them, especially some of them.” They hoped that if a minister were sent there would be “sufficient satisfaction and encouragement to stand our ground.”

In 1697, Samuel Wheelwright, then representative, petitioned that the taxes of Wells should be remitted, and that the soldiers should aid the inhabitants of Wells in rebuilding their garrisons, in view of the fact of “the distresses they are put unto, lying frontier to the enemy and often prest by their attack, and their fortifications much decayed and out of repair.” If their prayers are granted, they agree that “so will they rebuild and further adventure their lives and estates in standing their ground and defending their Majesties’ interests in those Eastern Parts.”347

At the close of the war, the people of Wells went actively into lumbering. Grants to build saw-mills at Great Falls, and later, to take logs wherever found, were given John Wheelwright and others by the General Court. To Samuel Wheelwright, also, was given a grant to build a saw-mill at the same place. Rosin and tar were manufactured. Life was simple, hard, and manly. The duties of the leaders of the settlement in peace and war were on a plane sufficiently wide to prevent them from becoming simply parochial.

Col. Samuel Wheelwright died 13 May, 1700. We have seen him early appointed magistrate at Wells by the King’s Commissioners. In 1677, he was representative at the General Court for York and Wells. In 1681, he was appointed by Charles II. one of the Provincial Council of Maine; in 1689, Judge of Probate; by William and Mary, Judge of the Court of Common Pleas. He was a member of the Massachusetts Council for the Province of Maine, 1695–1698.

This clause in his will has interest: “I do give and bequeath to Esther, my beloved wife, all my cattle of all sorts, with my negro servant named Titus.”

The vessels that brought rum and molasses to Wells brought slaves also. They were sold in open market at Wells and York; their offspring were disposed of with as little compunction by their masters, as their descendants would to-day sell a calf. The “institution” of slavery appears to have had greater vitality in the Province of Maine than elsewhere in New England. At York there was a slave factory, in which were kept several negro families whose children were regularly sold to those who chose to buy. Here was a germ of an industry like to that which in later times so flourished in the Old Dominion.

During the war of ’92, two companies of soldiers were quartered at John Wheelwright’s garrison. Finding the house too small for their accommodation, they tore it down; shortly afterwards, before the house could be rebuilt, the troops were ordered to another station. The government did not make restitution. Later, Wheel-wright rebuilt the house at his own expense.

In 1700, there was presented to the General Court the petition of John Wheelwright,348 then representative, which states “that by reason of a long and wasting warr the greatest part of the inhabitants are slaine or gone out of the Towne and butt about 6 houses left in which are about Twenty six or Twenty seven familyes and most of them extremely poor, and the Enemy did also burne the house which they had built for the publick worship of God.” They ask assistance now that peace was “concluded,” to rebuild their church and to pay their minister’s salary, “otherwise the ordinances of God will in great measure Sink among them, who are not able alone to afford a Subsistence to a Minister.” An order in Council was passed “for payment of fifteen pounds unto Mr. Samuel Emery, Minister of Wells.”349

War was declared against England by France in August, 1702. John Wheelwright wrote to Governor Dudley that, having had experience of the “horrible desatefulness” of the Indians, he did not trust their vows of friendship on which the Governor seemed to rely.

“Their teachers instruct them that there is no faith to be kept with Hereticks such as they account us to be.… This town being nearest the enemy and the farthest from any help or Relief, we cannot but apprehend ourselves to be in great danger, and especially at this season of the year, our necessities calling us generally from our homes to get our bay and corn secured. Our inhabitants do therefore pray that your Excellency should assist us with some men, twenty or thirtie.”

At the same time Wheelwright begged permission to build a garrison house at the Town’s End, or else he should be forced to carry a large family to “the middle of the town” where he had “but little to maintain them withal.” After some delay the permission to build the garrison house was granted, but too late to add to the strength of the town. On the tenth of August, 1703, it was surprised by the Indians. Wells then suffered the greatest disaster in its history; thirty-nine of its inhabitants were killed or captured, among them many of the Wheelwright kin. Two nephews of John Wheelwright — one a babe, the other a boy of five, children of William and Anne Parsons — were killed, and their young sister taken captive. The father and mother fled to York. The records of the Seigniory of St. Sulpice at Le Lac des Deux Montagnes350 show that Anne Parsons, with her daughter Catherine, was captured at York 22 August of the same year. Catherine was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church. The fate of her mother is unknown. Her father survived the destruction of his family but a few months.

In this raid on Wells, Esther, a daughter of Col. John Wheelwright, was captured. Her father tried in vain to effect her exchange. In his will, he pathetically mentioned “daughter Esther Wheelwright, if living in Canada, whom I have not heard from these many years, and hath been absent about thirty years.” Esther’s name appears in a Canadian list of English captives taken in the wars between New France and New England and baptized into the Roman Catholic Church. She is there recorded as an Ursuline nun, called “of the Infant Jesus.” She was, tradition says, Superior of the convent. She was buried at Quebec, 28 November, 1785. Letters from her to her family when in Canada are known to have been in existence; a piece of her embroidery, worked in the convent, with certain Indian curiosities, sent by her to her grand-niece, Esther Wheelwright of Roxbury, were seen, fifty years ago, by a member of the family now living. All trace of these letters and gifts is lost.

In this list of converted captives are the names of Mary (Rishworth) Plaisted, a cousin of John Wheelwright, and her two daughters. They were captured 25 January, 1692, probably in the attack on York.

In this connection extracts from letters of a later captive, Lieut. Josiah Littlefield, have interest. He writes from Montreal in 1708:

“Now I have liberty granted me to rite to my friends and to the governor, and for my redemption and for Wheelrite’s child to be redeemed by two Indian prisoners that are with the English now, and I have been with the Governor this morning and he has promised that if our governor will send them we shall be redeemed, for the Governor has sent a man to redeem Wheelrite’s child and do looke for him in now every day with the child to Moriel where I am, and I would pray Whelerite to be brief in this matter, that we may come home before winter.”

Another letter from Littlefield says: “I would pray you … Wheelwright dear friends to be mindful in the matter concerning our redemsion. I have riten to the governor at boston.”

After the raid of 1703, Wells was left in a pitiable condition. John Wheelwright headed this petition to the General Court, asking remission of taxes: —

“We who are the Frontier wing of the body of the Frontier towns are most of all impoverished and diminished. More than a third part of us who are left, being destitute of employment and income, are so exceeding poor that if the constable, who hath already used all means more gentle should execute the law in severity he must take their bodies.”

The General Court ordered a fair abatement of the tax levy.

In spite of the danger of outdoor work, John Wheelwright tore down that fall the house built by his grandfather at the “Town’s End,” and built on its site a new garrison house. Hostilities ceased, as was usual, with the coming of winter. In the spring, the Indians went again on the war-path. Refugees and the townspeople again flocked inside the palisades. The annals of this war record desultory attacks upon individuals and upon small parties. The Indians had found this method of work less dangerous to themselves and more harassing to the English than general attacks upon the town.

A man with a guard of three soldiers went out a mile from Wheelwright’s garrison to bring in cattle. A party of Indians, waylaid them on their return; two of the Englishmen were killed, and one captured. There were numerous captives taken and many persons killed from time to time.

The following year a party of Indians attacked Winter Harbor; Wells was warned by a messenger; the great guns gave warning to the people. The Indians made no attack. They hovered in the neighborhood and picked off stragglers. It was at this time that Lieutenant Littlefield, whose letters from Canada have been quoted, was captured.

The government finally made an aggressive campaign to the eastward and in Acadia, so that Wells was freed from Indian attacks until the fall of 1709, when a soldier was killed as he went between a garrison house and the village. The savages came again in the spring of 1710. They killed two men who were planting corn. During the next year, several people, surprised either in their fields or houses, were killed or wounded. The straits to which the people were reduced to find opportunity to plant for a crop, with any protection from Indian attack, is shown by the permission granted to certain persons to till the highway four rods wide in the neighborhood of John Wheelwright’s garrison house.

On the fifteenth of September, 1712, there was a great merry-making at John Wheelwright’s house. His daughter Hannah was married to Elisha Plaisted. The bridegroom came from his home at Portsmouth with a large escort of friends. Guests came, too, from all the country round. The whole party spent the night within the stockade.

In the morning, when some of the guests started for home, several horses were missing. The three men who went in search of the horses had gone but a short distance when two were killed, and the third wounded and captured by the Indians. The firing told the story at the garrison. The bridegroom and eight or ten others, with a rashness perhaps not unconnected with the festivities of the previous night, rushed to their horses and started in pursuit of the Indians. Two hundred savages, lurking in ambush, fired on the party. One was killed; all the horses were shot under their riders. The bridegroom was taken prisoner. The rest of the party retreated. Seventy men set out to give battle to the Indians, who were concealed in the forest. A slight skirmish took place, in which one man was killed on either side. A flag of truce was then sent out to learn upon what terms Plaisted’s ransom could be had. The Indians, knowing that they had a valuable prize, were in no haste to come to terms. They disappeared, taking with them their captives. The next that was heard of Plaisted was in this letter written to his father: —

Sir, —I am in the hands of a great many Indians, with which there are six captains. The sum that they will have for me is 50 pounds, and 30 pounds for Tucker, my fellow prisoner, in good goods, as broadcloth and some provisions, some tobacco pipes, pomistone, stockings, and a little of all things. If you will come to Richmond’s Island in five days at farthest, for here are two hundred Indians and they belong in Canada. If you do not come in five days you will not see me, for Captain Nathaniel, the Indian, will not stay no longer, for the Canada Indian is not willing to sell me. Pray, sir, do not fail, for they have given me one day for the days were but four at first. Give my kind love to my dear wife.

This from your dutiful son till death,

Elisha Plaisted.

When ransomed, Plaisted took his wife to Portsmouth.351 It is supposed that Hannah’s younger brother, Jeremiah, left the frontier with her. He lived in Portsmouth, and from him is descended the Newburyport branch of the family.

A treaty of peace was signed the following year. Wells then had respite from these savage raids. Her people were much impoverished, their tillage had been restricted through fear of attack, their houses, barns, and saw-mills burned, their cattle killed. Although lacking in material things, and not a little fallen from the standards of living brought from the mother country by the first settlers, these sons and grandsons of the Exeter Associates were, as the New England phrase goes, “real folks.” They had intelligence, fair education,352 physical strength, courage, and character qualities that made them good counsellors in peace and trusted leaders in war.

The social lines of this frontier community were drawn with sharpness. It would seem that civic or military service, with property and character, rather than the claims of descent, was the basis upon which such matters were decided. In the division of pew-holders into classes, the lines were distinctly drawn through their own brothers and kinsfolk.

After Queen Anne’s War, the several industries of Wells prospered. Its population increased. The vote of the town-meeting of March, 1716, shows that this increase of population was not thought to be an unmixed good by the old settlers who had fought in defence of the settlement. By this vote, which was signed by the landowners of Wells, headed by Col. John Wheelwright, the claim was made of “right and property of all common and undivided lands within said township, for themselves and for their heirs forever.”

In 1718, when the Scotch-Irish colonists from about Londonderry came to New England and had selected for their settlement the tract now called Londonderry, in New Hampshire, they were referred to Col. John Wheelwright to obtain title to the land, as “he had the best Indian title derived from his ancestors.” There were one or two other claimants of the same territory, a tract ten miles square, yet the government protected the settlers under Colonel Wheelwright’s deed, which is dated 20 October, 1719, in which he conveys “by virtue of a Deed or Grant made to his grandfather a minister of the Gospel 17 May 1629.”353

In 1722, the Indians again became hostile. In this and in the ensuing years, several persons in Wells and its neighborhood were killed. Lieutenant-Governor Dummer wrote to John Wheelwright, —

“Charge the people within the district of your regiment to be very careful when they go into the fields not to expose themselves by going out weak and without arms, but that they associate in their work in parties of ten or a dozen men, well armed, keeping a centinel with their guns.”

It would appear that these admonitions were little heeded; several parties and individuals at work in the fields were after this warning slaughtered by the Indians.

In August, 1724, three companies of English, in which were several men of Wells, attacked the Indian village of Norridgewock. Rale, the French priest, was killed, and the village destroyed.354

One incident of this war seems to reflect little credit on a son of Colonel Wheelwright, and, almost certainly, none on the men under his command. In November of the same year, Capt. Samuel Wheelwright355 was ordered to go with a company of fifty men to dislodge a party of Indians who were back of Ossipee Pond. The detachment delayed three days at Wells in making preparations. On account of the “heavy snow on the bushes,” they consumed six or seven days more in a march of sixty miles. Finally, the Captain’s journal says: “In the morning when I came to muster the men in order to march, some were sick, some lame, and some deadhearted, and the snow being somewhat hard, so that I could not get over 18 or 20 that were fit to march forward; upon which I called the officers together for advice, and so concluded to return again, which was contrary to my inclination.” Whatever Samuel’s “inclination” may have been, that of his men is only too evident; they accomplished the return journey in two or three days.

The “deadheartedness” of the Wells levy missed for its people the glory of sharing in Lovewell’s victory which practically ended this war; although, as this letter of Col. John Wheelwright to the Lieutenant-Governor, dated 27 October, 1726, shows, the people of the Province were still subject to savage maraudings: —

“Philip Durrell of Kennebunk, went from his house with one of his sons to work, the sun being about two hours high, leaving at home his wife, a son twelve years old, and a married daughter with a child 20 months old. He returned home, a little before sunset, when he found his family all gone, and his house set on fire, his chests split open and all his clothing carried away. He searched the woods and found no signs of any killed.”

It was later learned at a conference with the Indians that the boy was sold to the French and the other three killed.

Wells had suffered less in this than in previous wars. Not a few had been killed, but there had been no attack in force on the town. The Indians had found Wells a hard nut to crack in the past wars; now the number and strength of the garrison houses had been increased. In 1724, on the death of Mr. Emery, the minister, Col. John Wheelwright and Deacon Thomas Wells were appointed a committee to go to Boston and Cambridge to get some one to preach for several weeks. They were directed to apply first to Mr. Lowell, then to Mr. Thompson, then to Mr. Dennis. Mr. Thompson preached for six weeks and returned. Finally, Mr. Samuel Jefferds, a Harvard graduate of 1722, accepted the call. He married Sarah, daughter of Col. John Wheelwright. He lived in the manse, built in 1727, which was standing until three years ago.

In the spring of 1745, the fighting men of Wells, sixty-two strong, among them Thomas, the son of Joseph Wheelwright, rallied under Col. John Storer, to join that strangely combined muster and camp-meeting, the expedition against Louisburg. Probably there were few in the Provincial army who answered the summons to war with more alacrity than the men of Wells; a chance was offered to pay, with interest, their old scores against the French and Indians. Jeremiah Wheelwright, who went with the Plaisteds to Portsmouth, after the disagreeable ending of their nuptial festivities, was a lieutenant in a New Hampshire regiment in the Louisburg expedition.356

At this time, if we can trust the prejudiced statement of the people of Kittery in a petition for remission of their taxes, “Wells has excellent farms, a Lumber trade too. Seated in a Pleasant Bay for fish, a Wealthy and Careful People, Can Well Surport themselves and are as independent as any town in the County.”

Col. John Wheelwright died 13 August, 1745. He had been called “the bulwark of Massachusetts for defence against Indian assaults.” Besides his services at home, he had been an officer under Captain Convers, went to Pemaquid and Sheepscot, thence to Taconnet, and was afterwards stationed at Fort Mary on Saco River. In 1742, he and Eliakim Hutchinson, probably of Boston, were chosen representatives for Wells. He was appointed Commissioner to the Indians in 1717, and again in 1721,357 a Councillor of the Province, Judge of Probate, and of the Court of Common Pleas. His effigy, in judge’s robes, evidently from a portrait, is carved in low relief upon his tombstone in the “town lot,” at Wells.

This item in Col. John Wheelwright’s will is of interest: —

“In consideration of the love and affection I bear to my beloved wife, I give her all my cattle and creatures of every kind, negro and mulatto servants.”

When war was declared against France in 1753, a considerable levy went from Wells to serve under Wolfe in his Canadian campaign, among them Simon Jefferds, a grandson of Col. John Wheelwright; and there is a tradition that his son, Lieut. Jeremiah Wheelwright, of Portsmouth, was with Wolfe at Quebec. During this war, another grandson, Daniel Wheelwright, went to Fort Halifax. With the fall of Quebec, Wells ceased to be a frontier town.

In the later times of comparative freedom from Indian attack, Col. John Wheelwright probably prospered in his various enterprises, for we find his eldest son, John, a merchant in Boston before he was thirty. He is described as of “Boston and Wells.” He was a Councillor of the Province, as had been his father and grandfather. He died in 1760, in Boston, where he is buried in King’s Chapel burying-ground; on his tomb is carved a coat-of-arms.358

John Wheelwright’s eldest son Nathaniel359 was a merchant of London, England; his youngest son Joseph went to Halifax on the evacuation of Boston. Neither of these sons or their descendants ever returned to New England.

Job, son of Col. John Wheelwright’s second son Samuel, also settled in Boston; he was a protestor against Whigs in 1774. He is found in Boston after the Revolution, and from him is descended the Boston branch of the family.

The other sons of Samuel stayed at Wells; from them and from Joseph, the brother of Col. John Wheelwright, are descended all the Maine Wheelwrights; they were Whigs in the Revolution, as were the descendants of Jeremiah Wheelwright of Portsmouth. Several men of these families served the patriot cause in the Revolution.360

The descendants of the Rev. John Wheelwright and of his Exeter Associates were in successive generations until after the Revolution the recognized leaders at Wells. Men of their blood probably control its town affairs to-day. It is possible that the enterprises of the town may yield as much return now as a century or more ago, but relatively, as compared with developments elsewhere, Wells has no importance. Once the capital of the Province of Maine, it is now but a straggling farm village; its people, the descendants of the Exeter Associates and of the Bay Puritans, of the “gentlemen adventurers” and of the “poor whites” of “New Somersetshire” alike have merged into the mass of the country-folk of the Maine coast.

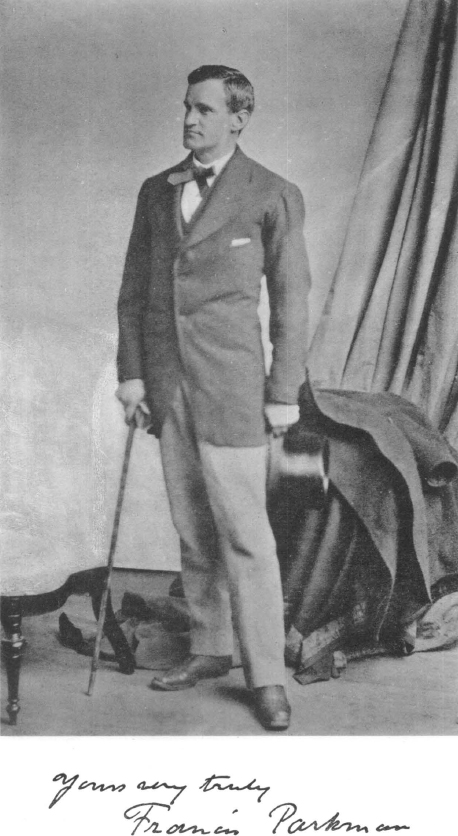

Mr. Edward Wheelwright communicated a Memoir of Francis Parkman for publication in the Transactions.

birth and ancestry.

Francis Parkman, eldest son of the Rev. Francis (H. C. 1807) and Caroline (Hall) Parkman, was born in Boston, Massachusetts, 16 September, 1823.

He was a lineal descendant, both on his father’s and on his mother’s side, of ancestors resident in the Colonies both of The Massachusetts Bay and of Plymouth prior to their union in 1692, and thus amply fulfilled one of the requisites for admission to The Colonial Society of Massachusetts.361 His earliest American ancestor in the paternal line, Elias Parkman, was living at Dorchester, Massachusetts, as early as 1633; while a progenitor on his mother’s side, John Cotton of Plymouth (as he was called, to distinguish him from his father, John Cotton of Boston), was pastor of the church in that town, to which he removed with his family in November, 1667; and his son Rowland, from whom Parkman was descended, was born in Plymouth in December of the same year.362

Mr. Parkman’s descent in the paternal line, through eight generations, is as follows: —

- 1. Thomas Parkman, of Sidmouth, Devon, England.

- 2. Elias Parkman, born in England, settled in Dorchester, Mass., 1633, married Bridget.

- 3. Elias, b. in Dorchester, Mass., 1635, m. Sarah Trask of Salem.

- 4. William, b. in Salem, Mass., 1658, m. Eliza Adams of Boston.

- 5. Ebenezer, b. in Boston, 1703, minister at Westborough, Mass.; m. (2d) Hannah Breck.

- 6. Samuel, b. in Westborough, m. (2d) Sarah Rogers.

- 7. Francis, b. in Boston, 1788, m. (2d) Caroline Hall.

- 8. Francis, b. in Boston, 1823.

The following is his descent on the mother’s side, through the same number of generations, from John Cotton: —

- 1. John Cotton, b. in England, 1585, m. (2d) Sarah Hankredge of Boston, England, widow of William Story. Came to Boston, 1633.

- 2. John Cotton, b. in Boston, Mass., 1639, m. Joanna Rossiter.

- 3. Rowland Cotton, b. in Plymouth, 1667, m. Elizabeth Saltonstall, widow of Rev. John Denison.

- 4. Joanna Cotton, b. in Sandwich, 1719, m. Rev. John Brown of Haverhill, Mass. (H. C. 1714.)

- 5. Abigail Brown, born in —, m. Rev. Edward Brooks of Medford.

- 6. Joanna Cotton Brooks, b. in —, 1772, m. Nathaniel Hall of Medford.

- 7. Caroline Hall, b. in Medford, 1794, m. Rev. Francis Parkman of Boston.

- 8. Francis Parkman, b. in Boston, 1823.

Of Elias Parkman, his first American ancestor, it is known that he resided in Dorchester, Windsor, Ct., and lastly Boston, and that he married and had nine children, — six sons and three daughters. Two of the sons, John and Samuel, appear to have gone to Virginia. Two daughters were married: one, Abigail, to John Trask, of Salem; the other, Rebecca, to John Jarvis, of Boston. Elias, the eldest son, married a daughter of Captain William Trask, of Salem, and resided in that town till 1662–63, when he removed with his family to Boston. His death took place at Wapping, London, England, in 1691.

William, eldest son of Elias and Sarah (Trask) Parkman, born in Salem 29 March, 1658, was in 1712 one of the original members, and afterward a ruling elder, of the New North Church in Boston.363 He married, in 1680, Eliza, daughter of Alexander and Mary Adams, of Boston, and died in Boston, 30 November, 1730. He was buried in the graveyard on Copp’s Hill.