EDITOR’S FOREWORD

Josiah Quincy Jr.’s Southern Journal (1773)

Daniel R. Coquillette

This new transcription and edition of Josiah Quincy Jr.’s extraordinary southern adventure has been an adventure in itself. My fellow travelers have been my exceptional research assistants: Michael H. Hayden, Boston College Law School Class of 2004, Nicole Scimone, Boston College Law School Class of 2005, Susannah B. Tobin, Harvard Law School Class of 2004, and Elizabeth Papp Kamali, Harvard Law School Class of 2007. Michael Hayden also provided the transcription, which is a true labor of love, and many of the annotations. Without all this great effort, the project would have been impossible. All in all, this was a team effort, and it has been a privilege to work with such outstanding young people.

The manuscript of the Southern Journal is at the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston in the Quincy, Wendell, Holmes and Upham Family Papers (hereafter “Quincy Papers”) microfilm P-347, Reel 3, Ms. QP-61, JQII. It was first printed in Josiah Quincy, Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy Jun. (1st ed., Boston, 1825), pp. 73–141 (hereafter “Memoir”), a book actually prepared in most part by Quincy’s granddaughter, Eliza Susan Quincy (1798–1884), but published under her father’s name. Eliza prepared a second edition in 1874, in which the Southern Journal appears at pp. 56–111. Both of these versions are unreliable, Eliza having excised important material. As she noted: “Some of his particular observations, from the familiarity of our present intercourse, might appear trite and uninteresting, and will be omitted, as also will be, for the most part, all those particular strictures on the nature of the population of the southern colonies, which was most likely to make the deepest impression on an inhabitant of the northern, and by which a stranger, of his turn of mind, could not fail to be peculiarly affected.” See Memoir, supra, pp. 72–73. Needless to say, these omissions include particularly interesting material! Eliza also omitted important materials from Quincy’s letter to his wife of March 1, 1773, from Charleston. See Memoir, supra, pp. 71–73, 2d ed., pp. 73–96. For a full account of Eliza Quincy’s literary activity, see Neil L. York’s “Prologue” and “The Making of a Patriot: A Life Cut Short” at pp. 10–11, 15 in volume 1 of this series, Portrait of a Patriot: The Major Political and Legal Papers of Josiah Quincy Jr. (hereafter “Quincy Papers”).

The Southern Journal has only been published once before in an unexpurgated version, by the legendary Mark Antony DeWolfe Howe in the Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. XLIX (October 1915–June 1916), pp. 426–481 (hereafter, “Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916”). Howe, who was related to the Quincy family by marriage, also transcribed Quincy’s London Journal, an account of his voyage to London in 1774–1775, which has been newly edited for these volumes by my co-editor, Neil Longley York, in Volume 1 of the Quincy Papers, supra. Professor York has included a compelling short biography of Howe at Volume 1, pp. 219–221, which I will not attempt to repeat here.

This new transcription and edition of the Southern Journal was done directly from the manuscript, and is more accurate than the earlier version. Where, however, Howe’s annotations proved valuable, they have been retained, with citations to the Proceedings.

Such a massive project would have been impossible without the extraordinary efforts of the transcriber, Michael H. Hayden, Esq., Boston College Law School Class of 2004 and Member of the Massachusetts bar. In so many ways, Mr. Hayden was the ideal student, research assistant, and colleague. Enthusiastic, original, and thorough, he has an exceptional historical sense and a taste for grinding hard work. The quality and care of the transcription, which, unlike Howe’s, reproduces each page of the manuscript, is a labor of love. Further, Mr. Hayden provided a large number of the annotations and illustrations, with this co-editor taking responsibility for the rest, together with any errors. Mr. Hayden’s Transcriber’s Foreword, which follows, gives only a brief glimpse of his scholarship and dedication.

I should also again acknowledge the loyal and intelligent assistance of Susannah Tobin, Harvard Law School Class of 2004, who provided the Latin translations, Elizabeth Kamali, Harvard Law School Class of 2007, who reviewed them, and Nicole Scimone, Boston College Law School Class of 2005, who labored long and hard to supplement the annotations and to locate the many wonderful illustrations. As always, it has been an exceptional pleasure to work with my co-editor, Neil Longley York, Karl G. Maeser Professor at Brigham Young University and Chair of the History Department, and John W. Tyler, Editor of Publications to the Colonial Society of Massachusetts and Chair of the History Department at Groton. They are both gentlemen and scholars in every sense of the word. Finally, special thanks are due to that great institution and guardian of our nation’s history, the Massachusetts Historical Society, its exceptional Librarian, Peter Drummey, and to the Quincy family, who have taken a close interest in this project.

THE TEXT

The text has been reproduced as closely as possible to the manuscript itself, with each page printed as it appears in the manuscript. This is a major improvement on the expurgated, if not censored, version of Eliza Quincy and on Howe’s transcription. Thanks to the extraordinary efforts of Michael H. Hayden, we have Quincy’s original page numbering, and the important distinction between Quincy’s text and the margin notes. Each line corresponds exactly to the lines in the original. See Michael Hayden’s Transcriber’s Foreword, infra, for his sensitive treatment of spelling and abbreviations.

Where useful, some of Howe’s annotations have been retained, with a citation to “Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916,” but the notes have been greatly expanded and brought up-to-date. Howe actually annotated the Southern Journal very lightly compared to his edition of the London Journal, with 97 notes over 55 pages for the former, and 176 notes over 37 pages for the latter. This new edition has 327 notes and 24 illustrations, plus an index.

The Transcriber’s Foreword also discusses the mystery of the missing pages 125 and 126, which were cut out by a blade. Quincy also crossed out lines at pages 81 and 92, and left blanks on pages 138 (where he could not recall a name), on page 155 (where he did not wish to enter Benjamin Franklin’s name), on page 159 (where he could not recall the first name of a “Dr. Cox”), and on page 164, in the middle of a discussion of Pennsylvania’s politics. These blanks are all indicated where they occur in the original manuscript. There are also some most interesting later inserts, ably discussed by Michael Hayden in the Transcriber’s Foreword, infra.

* An abbreviated version of this introduction was published as Daniel R. Coquillette, “Sectionalism, Slavery, and the Threat of War in Josiah Quincy Jr.’s 1773 Southern Journal,” 79 New England Quarterly (2006), pp. 181–201.

1. See the discussion in Bruce Redford, Venice and the Grand Tour (New Haven, 1996), pp. 5–25. See also Jeremy Black, The Grand Tour in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1999).

2. See biographical sketch in Law in Colonial Massachusetts (editors D. R. Coquillette, R. J. Brink, C. S. Menand, Boston, 1984), pp. 350–351. (Hereafter, “Law in Colonial Massachusetts!”)

3. See Gordon S. Wood’s excellent discussion in The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York, 2004), pp. 105–151.

4. Compare the “rough travel” journals set out in Travels in the American Colonies (Newton D. Mereness, ed., 1st published 1916, reprinted, 1961, New York).

5. Southern Journal, p. 3. Sailing packets rivaled steam craft for speed well into the nineteenth century. See Seymour Dunbar, A History of Travel in America (Indianapolis, 1915), vol. 2, pp. 372–392.

6. John Harrison (1693–1776) finished his famous chronometer “H-4” in 1759, but he was not acknowledged as solving the longitude “problem” until 1773, the year of Quincy’s voyage. Although Captain James Cook tested chronometers successfully between 1772 and 1775, they were not generally deployed on commercial vessels until the nineteenth century. See Derek House, Greenwich Time and the Discovery of the Longitude (Oxford, 1980), pp. 71–72. The only usual methods to calculate longitude before the chronometer was the complex “lunar distance” method or “dead reckoning” using a ship’s log to calculate speed through the water, a highly inaccurate method. Id., pp. 16, 54, 194–197. Both would have been useless in a storm like the one experienced by Quincy. See also, Rupert T. Gould, The Marine Chronometer: Its History and Development (London, 1923), pp. 40–70; The Quest for Longitude (ed. William J.H. Andrews, Cambridge, 1996), pp. 235–254; and Dava Sobel, Longitude (New York, 1995), pp. 152–164.

7. In 1786, it still took four to six days just to go to New York, from Boston, by road, depending on the weather. Major road improvements took place between 1790 and 1840. See Jack Larkin, The Reshaping of Everyday Life 1790–1840, pp. 205–211.

8. See York, Introduction, Quincy Papers, vol. 1 at pp. 35, 43.

9. See Alice Morse Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days (New York, 1898), pp. 325–363. Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York, 1992), pp. 24–56. (Hereafter “Wood, Radicalism.”)

10. Southern Journal, p. 42. Note, all footnote citations to the manuscript are to Quincy’s original pagination, carefully retained in this edition.

11. See Larkin, The Reshaping of Everyday Life 1790–1840, supra, pp. 211–213.

12. See Alice Morse Earle, Home Life in Colonial Days (New York, 1898), p. 346.

13. Id., p. 346.

14. Id., p. 348. “The traveler Weld, in 1795, gave testimony that the bridges were so poor that the driver had always to stop and arrange the loose planks ere he dared to cross.” Id., p. 348.

15. Id., p. 349.

16. See Southern Journal, pp. 87–88.

17. York, Introduction, vol. 1, supra, pp. 27–28.

18. See Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, vol. XV: Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College in the Classes 1761–1763 (Boston, 1970), pp. 348–349 (hereafter, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates). Quincy’s age was listed as “13’14.” Id., p. 348. See Neil L. York’s excellent biographical introduction to volume 1 of this series, “A Life Cut Short,” Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. 15ff.

19. See Southern Journal, p. 132. In this, Quincy would recognize his future collaborator, Benjamin Franklin, as a “gentleman” despite his origins in trade. “In 1748, at the age of forty-two, Franklin believed he had acquired sufficient wealth and gentility to retire from active business. This retirement had far more significance in the mid-eighteenth century than it would today. It meant that Franklin could at last become a gentleman, a man of leisure who no longer would have to work for a living.” Gordon S. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York, 2004), p. 55. (Hereafter, “Wood, Franklin”) See generally, Id., pp. 17–60, “Becoming a Gentleman.”

20. Southern Journal, p. 132.

21. Quincy was never formally made a barrister, although he argued cases before the Superior Court of Judicature. “I argued … to the Jury, though not admitted to the Gown: ___ The Legality and Propriety of which some have pretended to doubt; but as no Scruples of that kind disturbed me, I proceeded (manger any) at this Court to manage all my Business … though unsanctified and uninspired by the Pomp and Magic of—the Long Robe,” Reports, p. 317. His great-grandson Samuel noted that this was due to “[t]he political course of Mr. Quincy having rendered him obnoxious to the Supreme Court of the Province …” Id., p. 317 n. (1), quoting Quincy’s Life of Quincy, p. 27. The truth of that loyal remark is hard to judge. Certainly the like of John Adams and James Otis Jr. were admitted to the bar, but earlier. See Reports, p. 35, Memorandum of 1762 listing the members of the bar.

22. Gordon S. Wood, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (New York, 1992), p. 24. (Hereafter “Wood, Radicalism.”) See also Ronald Schultz, “A Class Society? The Nature of Inequality in Early America,” Inequality in Early America (Hanover, N.H., 1999), p. 203. Schultz believes that America only became “a true class society” in the 1880s. See Id., p. 216.

23. See Richard R. Beeman, The Varieties of Political Experience in Eighteenth-Century America (Philadelphia, 2004), pp. 1–30. (Hereafter, “Beeman.”)

24. See Southern Journal, infra, p. 53.

25. Id., p. 57. Quincy was horrified by dinner conversation indicating that “to steal a negro was death, but to kill him was only fineable” (emphasis in original). His reaction at the table, however, was to say “Curious laws and policy!” Id., p. 57.

26. Id., p. 98.

27. Id., pp. 96, 98–99.

28. Id., p. 138. On Dulany’s fate as a loyalist, see Dictionary of American Biography (New York, 1943), V, p. 499.

29. Id., p. 89.

30. Wood, Radicalism, supra, p. 101.

31. Id., p. 99.

32. Id., p. 99.

33. Id., p. 99.

34. Southern Journal, p. 88.

35. The Estate Catalogue of Quincy’s library indicated a “Cicero Thoughts” as Item 256. Quincy Estate Catalogue, Quincy Papers, vol. 5 (Appendix 9). This book was probably the popular English translation Thoughts of Cicero. “First published in Latin and French by the Abbé d’Olivet.” The translator was Alexander Wishart. It was first published in London in 1751, then in Glasgow in 1754, and again in London in 1773. Thomas Jefferson had the Glasgow edition in his library [7.84]. See Catalogue of the Library of Thomas Jefferson, vol. II (Charlottesville, 1983), p. 37. The book consisted of translated extracts from Cicero’s most famous letters, tracts, and speeches, including De Legibus (begun 52 b.c., not published until after Cicero’s death in 43 b.c.), the Tusculum Disputations (45–44 b.c.) and his letters to his brother, Ad Quintum Fratrem (59–54 b.c.). See The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (2d ed., M. C. Howatson, ed., 1989), pp. 131–134. In his Political Commonplace, item 97, Quincy quoted from Cicero’s “Oration for Sextius,” Pro Sextus Roscias (80–79 b.c.). “The Republic is always attacked with greater vigour than it is defended … whereas the honest … when they would be glad to compound at last for their quiet, at the expence of their honour, they commonly lose them both.” See Political Commonplace, Quincy Papers (Hereafter, “Political Commonplace”), volume 1, pp. 138–139, 204. See also The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (M. C. Howatson, ed., Oxford, 1989), pp. 128–134. (Hereafter, “Howatson.”)

36. Wood quotes Conyers Middleton’s popular Life of Cicero (1741). “[N]o man, how nobly soever born, could arrive at any dignity, who did not win it by his personal merit.” Wood, Radicalism, supra, p. 100.

37. On entail, see Dudley v. Dudley, Reports, p. 12; Elwell v. Pierson, Reports, p. 42; and Baker v. Mattocks, Reports, p. 69. On extent of liability for a husband’s debts, see the famous “naked wife” case, Hanlon v. Thayer, Reports, p. 99. On the harsh threat of execution to the mother of a stillborn child if she could not prove she was married, due to a statutory presumption of murder, see Dom. Rex v. Mangent, Reports, p. 162. There were also cases on the husband’s liability to support an abandoned wife and children. See Brown v. Culnan, Reports, p. 66. Interestingly enough, the only woman to feature in Quincy’s Reports in a business context was indicted for “keeping a bawdy house.” See Dom. Rex v. Doaks, Reports, p. 90.

38. See J. H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History (4th ed., London, 2002), pp. 272–296 (hereafter, “Baker”); Marylynn Salmon, Women and the Law of Property in Early America (Chapel Hill, 1986), pp. 81–90. See generally, Susan Stevas, Married Women’s Separate Property in England 1660–1833 (Cambridge, Mass., 1990).

39. See the extensive discussion in the note to Baker v. Mattocks, Reports, p. 69.

40. See the extensive discussion in the notes to Dudley v. Dudley, Reports, p. 12. Virginia, on the other hand, made it particularly difficult to bar entails, even prohibiting the “Common Recovery” fiction for barring entails used in England. See Baker, supra, pp. 281–283. Quincy disapproved. “An Artistocratical spirit and principle is very prevalent in the Laws policy and manners of this Colony, and the Law ordaining that Estates—tail shall not be barred by Common Recoveries is not the only instance thereof.” Southern Journal, p. 128.

41. See also the discussion in the notes to Elwell v. Pierson, Reports, p. 42. See “Baron & Feme,” Law Commonplace, Quincy Papers, vol. 2, pp. 25–28 citing Quincy’s pagination. (Hereafter, “Law Commonplace.”) For a good account of the legal status of colonial women, see Mary Beth Norton, “Either Married or to Bee Married: Women’s Inequality in Early America,” in Inequality in Early America (eds. C. G. Pertand, S. V. Salinger, Hanover, N.H., 1999), pp. 25–45.

42. In this case, the mother’s life was saved when the court held that a marriage license by an out-of-state clergy was admissable “without any authentication from any Magistrate.” See the extensive notes to Dom. Rex v. Mangent, Reports, p. 162.

43. See Southern Journal, p. 1, n. 1.

44. See London Journal, Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. 267–269.

45. See Neil L. York, Introduction, vol. 1, pp. 44–45. Five years after her husband’s death, Abigail wrote, “I have been after told, that time would wear out the greatest sorrow, but mine I find is still increasing. When it will have reached its summit I know not.” Id., p. 44.

46. See Southern Journal, p. 45, n. 57.

47. Id., at p. 113.

48. Id., at p. 45.

49. Id., at p. 45. Quincy wrote to his brother Samuel on April 6, 1773: “I saw little of that exuberance, hilarity and roar which are so incident to a Northern festival and entertainment: Indeed in point of genuine vivacity and fire the Northern Bells and Sparks surpass those of the South whose spirit and blaze seem exhausted or extinguished by a warmer sun.” Dana Mgs. (Massachusetts Historical Society), Sibley’s Harvard Graduate, vol. XV, supra, p. 484.

50. Id., at pp. 90–95.

51. Id., at p. 89.

52. Id., at p. 67.

53. See Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 43–56. See also Ruth H. Bloch, Gender and Morality in Anglo-American Culture, 1650–1800 (Berkeley, 2003), pp. 1–17.

54. Cara Anzilotti, In the Affairs of the World: Women, Patriarchy and Power in Colonial South Carolina (Westport, Conn., 2002), p. 193.

55. See “Editor’s Introduction,” Beyond Image and Convention: Explorations in Southern Women’s History, J. L. Coryell, M. H. Swain, S. C. Treadway, E. H. Turner eds. (Columbia, S.C., 1998), pp. 1–9; Mary Beth Norton, Founding Mothers & Fathers: Gendered Power and the Forming of American Society (New York, 1996); Patricia Cleary, “She Will Be in the Shop: Women’s Sphere of Trade in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia and New York,” 119 Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1995), 181–202; Elizabeth Anthony Dexter, Colonial Women of Affairs: A Study of Women in Business and the Profession in America Before 1776 (Cambridge, Mass., 1924), pp. 180–194; and Ruth H. Bloch, Gender and Morality in Anglo-American Culture 1650–1800, pp. 363–373.

56. Id., supra, p. 180.

57. Southern Journal, p. 149.

58. Id., p. 174.

59. Id., p. 178.

60. Id., p. 175.

61. Id., p. 176.

62. Id., pp. 49–50.

63. Id., p. 50.

64. Id., p. 47.

65. Id., p. 49. See also, id., p. 66. “Two ladies being called on for toasts, the one gave—‘Delicate pleasures to susceptible minds.’ The other, ‘When passions rise may reason be the guide.’” Id., p. 66.

66. Id., p. 170.

67. Id., p. 170.

68. See note 37, supra.

69. See Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 43–56. See also Laurel T. Ulrich, Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England 1650–1750 (New York, 1982), pp. 237–241 (hereafter, “Ulrich”); and Kathleen M. Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches and Anxious Patriarchs (Chapel Hill, 1998), pp. 367–373.

70. See note 56, supra.

71. See Ulrich, supra, pp. 237–241.

72. See the annotations at Reports, p. 29.

73. See the annotations at Reports, p. 94.

74. See the annotations at Reports, p. 74.

75. See Oscar Reiss, Blacks in Colonial America (Jefferson, N.C., 1997), pp. 65–72. (Hereafter “Reiss.”)

76. See the discussion at Reports, p. 95. Quincy cited to Smith v. Brown and Cooper, 2 Salkeld’s Reports 666 (1706) and Smith v. Gould, 2 Salkeld’s Reports, pp. 666–667 (1706). See also 2 Lord Raymond’s Reports, pp. 1274–1275, for another report of Smith v. Gould with the head note “Trover does not lie for a negroe.” Id., p. 1274. [Trover was the general cause of action for recovering the value of goods against another.] In the former case, Chief Justice Holt held “that as soon as a negro comes into England, he becomes free one may be a villein in England, but not a slave.” Smith v. Brown and Cooper, 2 Salkeld’s Reports (1706) at p. 666. But he added this advice to the plaintiff, who sought to recover £20 “for a negro sold by the plaintiff to the defendant,” by the contractual action of indebitatus assumpsit

Holt, C.J. You should have averred in the declaration, that the sale was in Virginia, and, by the laws of that country, negroes are saleable: for the laws of England do not extend to Virginia, being a conquered country in their law is what the King pleases; and we cannot take notice of it but as set forth; therefore he directed the plaintiff should amend, and the declaration should be made, that the defendant was indebted to the plaintiff for a negro sold here at London, but that the said negro at the time of sale was in Virginia, and that negroes, by the laws and statutes of Virginia, are saleable as chattels. Id., pp. 666–667.

The report in Smith v. Gould, supra, was even more ambiguous. This also involved “trover,” an action for recovery of the value of goods.

Lastly, it was insisted, that the Court ought to take notice that they were merchandize, and cited 2 Cro. 262. The case of monkeys, 2 Lev. 201. 3 Keb. 785. 1 Inst. 112. If I imprison my negro, a habeas corpus will not lie to deliver him, for by Magna Charta he must be liber homo. 2 Inst. 45. Sed Curia contra, Men may be the owners, and therefore cannot be the subject of property. Villenage arose from captivity, and a man may have trespass quare captivum suum cepit, but cannot have trover de gallico suo. And the Court seemed to think that in trespass quare captivum suum cepit, the plaintiff might give in evidence that the party was his negro, and he bought him. Id., p. 667.

The head note reads “Trover lies not for a negro; but in trespass quare captivum suum cepit, plaintiff may give in evidence that he was his negro.” Id., p. 667.

Given Quincy’s personal opposition to slavery, so strongly reflected by the Southern Journal, the marginal note may reflect his view of what the law should be in Massachusetts, rather than what it was.

77. Reports, p. 98. As Samuel Quincy noted, the Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature upheld a trover action for a negro in 1763. Id., p. 98. See Goodspeed v. Gay, Barnstable, Records 1763, Vol. 47. Slavery was finally abolished in Massachusetts by Quok Walker and Nathaniel Jennison case between 1781–1783. See Reiss, supra, pp. 71–72, William O’Brien, “Did the Jennison Case Outlaw Slavery in Massachusetts?” 17 (3d series) William and Mary Quarterly (April 1960), pp. 224–233; and Robert M. Spector, “The Quok Walker Case (1781–1783): The Abolition of Slavery and Negro Citizenship in Early Massachusetts,” 52 Journal of Negro History (1968), pp. 12–16.

78. Reiss reports that “[i]n Boston … a runaway named Josiah Quincy was saved when a mob beat a marshal trying to do his duty.” Reiss, supra, p. 194.

79. Southern Journal, p. 91.

80. Id., p. 95.

81. Wood, Radicalism, supra, p. 54.

82. See Law Commonplace, supra, “Of Apprentices & Servant,” pp. 19–21, and the annotations. Hutchinson vetoed a bill in 1771 barring the importation of slaves into Massachusetts, pointing out that “a slave was in no worse position than ‘a servant would be who had bound himself for a term of years exceeding the ordinary term of human life.’” See Bernard Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), p. 378. (Hereafter, “Bailyn, Ordeal.”)

83. Wood, Radicalism, supra, p. 55.

84. Southern Journal, p. 84.

85. Id., p. 82. For a typical large plantation of the area, see Illustration 2.

86. Id., p. 89.

87. Id., p. 80.

88. Id., p. 89.

89. Id., pp. 56–57.

90. Id., pp. 113–114.

91. Id., pp. 92–93.

92. Id., p. 110.

93. Id., p. 114.

94. Id., p. 57. (Italics in original.)

95. Quincy thus anticipated the central issue of Dred Scott v. John F. A. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 Howard) 393 (1857). As Chief Justice Roger Taney put it, it was not an issue of property law, but whether any person “of that class of persons … whose ancestors were negros of the African race, and imported into this country, and sold and held as slaves” could ever be citizens “when they are emancipated, or who are born of parents who had become free before their birth.” Id., p. 403. “The question is simply this: Can a negro, whose ancestors were imported into this country, and sold as slaves, become a member of the political community formed and brought into existence by the Constitution of the United States.” Id., p. 403. Free black or not, the answer was “no.” The issue was race, not property rights.

96. Southern Journal, pp. 91–92.

97. Beeman, supra, p. 135. See also Reiss, supra, pp. 108–114. The ratio of whites to blacks in North Carolina was 4 to 1, Id., p. 115. The 1790 census, the first official census, gave the total white population of South Carolina as 140,178 with 107,094 slaves and only 1,801 free blacks. This, of course, included the back country, where slaves were less numerous than in the plantations on the rivers. By comparison, there were only 948 slaves in a population of 68,825 in Rhode Island. Slavery was already abolished in Massachusetts, although those who owned slaves were allowed to keep them even after 1780. Courtesy U.S. Census Bureau.

98. See infra, p. 34, fn. 105.

99. In this observation, too, Quincy was in the vanguard of shifting opinion. As Michael Greenberg has demonstrated, “[c]riticism of the morality of slaveholding increased as more and more people realized that slave labor was incompatible with the ethical and material basis of a market society.” Michael Greenberg, “Of Men and Markets: Slavery and the Development of the Virginia Planter Class,” in Essays on Eighteenth Century Race Relations in the Americas, J. S. Saeger, ed. (Bethlehem, Pa., 1987), p. 73.

100. Southern Journal, pp. 109–110.

101. Id., pp. 92–93.

102. See A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., Barbara K. Kopytoff, “Racial Purity and Interracial Sex in the Law of Colonial and Antebellum Virginia,” 77 Geo. L.J. 1967 (1989) at pp. 1989–2007; Brown, Good Wives, Nasty Wenches and Anxious Patriarchs, pp. 194–211.

103. Southern Journal, p. 113.

104. Id., p. 91.

105. Id., p. 92.

106. Id., p. 110.

107. Id., pp. 91–93.

108. Id., p. 114.

109. Id., p. 93.

110. Id., p. 94.

111. Id., p. 113.

112. Id., p. 114.

113. Id., pp. 93–94, notes omitted. See annotations at text. Quincy frequently used Latin maxims to store and convey legal ideas. See the discussion at “Introduction to the Law Commonplace,” Quincy Papers, vol. 2. As to slavery, Quincy once again anticipated modern scholarship, which has described the vicious effect of slavery and racism on colonial jurisprudence. See A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr., Anne F. Jacobs, “The ‘Law Only as an Enemy’: The Legitimization of Racial Powerlessness through the Colonial and Antebellum Criminal Laws of Virginia,” 70 N.C.L. Rev. 969 (1992), 984–1016. (Hereafter, “Higginbotham, Jacobs.”) “Under this legalized system of ‘stripes and death,’ blacks had the worst of both worlds: they received almost no protection from cruelty and slaughter and were punished far more severely than whites. They were treated as less than human whenever it benefited the economic interests of the white master or the white power structure. Yet, when it came to punishing them, blacks were held to a more rigorous standard than whites. Not only were they punished more harshly for the same offenses whites committed, but they also risked execution and dismemberment for conduct that was legal for whites. Referred to as ignorant, immoral, and savage, they were expected to conform to a system of laws that legitimized cruelty and rendered them powerless.” Id., p. 1068, (notes deleted). See also Sally Hadden’s excellent Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge, Mass., 2001) and C.W.A. David, “The Fugitive Slave Law of 1739,” 9:1 Journal of Negro History (Jan. 1924), p. 18, at pp. 21–23; David Meaders, “South Carolina Fugitives,” 60:2 Journal of Negro History (April 1973), p. 291.

114. The classic statement of “The Absolute Rights of Individuals” at common law had just been published by William Blackstone in the first volume of his Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford, 1765), pp. 117–141. These include “a person’s legal and uninterrupted enjoyment of his life, his limbs, his body, his health, and his reputation,” Id., p. 125, as guaranteed by the Magna Carta, The 1628 Petition of Right, The 1689 Bill of Rights and other key English constitutional documents. Id., pp. 123–125. Blackstone proudly proclaimed that “[T]his spirit of liberty is so deeply implanted in our Constitution, and rooted even in our very soil, that a slave or a negro, the moment he lands in England, falls under the protection of the laws, and with regard to all natural rights becomes eo instanti a free man.” Id., 123. This doctrine was, of course, not applied in the colonies or even, as a practical matter, in England. Lord Mansfield, as late as 1772, “employed every technical device to evade a declaration upon the legality of slavery.” C.H.S. Fifoot, Lord Mansfield (Oxford, 1936), p. 41. As to Mansfield’s final and famous resolution of the issue in Sommersett’s Case, 20 St. Tr. 1 (1772), see Steven M. Wise’s fine book, Though the Heavens May Fall: The Landmark Trial that Led to the End of Human Slavery (Cambridge, Mass., 2005). For a full discussion of the English constitutional documents, see Daniel R. Coquillette, The Anglo-American Legal Heritage (2d ed., 2003, Durham, N.C.), pp. 59–63, 311–326, 366–368.

115. Southern Journey, pp. 56–57. For an excellent account of “plantation and extrajudicial justice” and how “the law actually sanctioned the master’s private law-enforcement authority over the slaves,” see Higginbotham, Jacobs, supra, pp. 1062–1067. For context, see George C. Rogers Jr., Charleston in the Age of the Pinckneys (Columbia, S.C., 1980), pp. 26–88; Weir, Colonial South Carolina, pp. 173–203; Robert Bosen, A Short History of Charleston (2nd edition, Charleston, 1992), pp. 67–79.

116. See the Law Commonplace, “Apprentices & Servants,” pp. 19–21; and “Baron & Feme,” pp. 25–29.

117. Southern Journal, p. 93.

118. Id., pp. 94–95.

119. See “III. Gentility,” p. 18 supra. Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 95–109.

120. Id., pp. 100–101.

121. Id., p. 110.

122. See text at notes 72–77, supra.

123. Southern Journal, pp. 87–88.

124. Exploiting distrust of Massachusetts and its leaders has a long and continuing history, as Presidential candidates Governor Dukakis and Senator Kerry can attest.

125. Southern Journal, p. 54.

126. Id., p. 55.

127. Id., p. 55.

128. Id., p. 94.

129. Southern Journal, pp. 134–135. On religious practices in the colonies, see Patricia U. Bonomi, Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America (New York, 1986); Richard Pointer, Protestant Pluralism and the New York Experience: A Study of Eighteenth Century Religious Diversity (Bloomington, Ind., 1988). See also Sally Schwartz, “A Mixed Multitude”: The Struggle for Toleration in Colonial Pennsylvania (New York, 1987); Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, Mass., 1992); and Roger Finke and Rodney Stark, The Churching of America, 1776–1990 (New Brunswick, N.J., 1992). (Hereafter, “Finke and Stark.”)

130. See Section “A,” p. 42 infra.

131. Frank Lambert, The Founding Fathers and the Place of Religion in America (Princeton, 2003), p. 206. (Hereafter “Lambert.”)

132. Southern Journal, p. 88.

133. Id., p. 86.

134. Id., pp. 87–88.

135. Id., pp. 165–166.

136. Id., p. 51.

137. Id., p. 51.

138. Id., p. 51.

139. Id., p. 52.

140. Id., p. 52.

141. Id., p. 52.

142. Id., p. 52.

143. Id., p. 52.

144. Id., p. 89.

145. See discussion at Sec. V, “Race and Slavery,” supra.

146. Southern Journal, p. 111.

147. Did Eliza S. Quincy, in shock, cut these out? Or was it her father, Josiah the Mayor? It is a mystery. See the discussion in the Editor’s Foreword and the Transcriber’s Foreword, supra.

148. Southern Journal, p. 124.

149. Id., pp. 134–135.

150. See Lambert, supra, pp. 73–99. Massachusetts only discontinued tax support for religion in 1833. Id., p. 223.

151. Southern Journal, pp. 135–136. Quincy noted that “[t]here are upwards of 5000 Roman Catholicks in this province,” id., p. 140, but the Calvert proprietors had renounced Catholicism in 1715 for Anglicanism. By 1773, Catholics were still tolerated, but were a distinct minority. They had never been a majority. As Roger Finke and Rodney Stark observed, “Founded by Lord Baltimore as a haven for Roman Catholics, Maryland was the most Catholic colony in 1776. But that wasn’t very Catholic—about three people in a hundred.” Finke and Stark, supra, p. 30. Anglicanism was the established religion. See Id., p. 140, note 222.

152. “I was however upon the whole much gratified, (and believe if I had stayed in town a month should go to the Theatre every acting night.) But as a citizen and friend to the morals and happiness of society I should strive hard against the admission and much more the Establishment of a Playhouse in any state of which I was a member.” Id., pp. 174–175.

153. Id., p. 150. Quincy attended a Moravian service, with mixed results. See p. 46 and note 160, supra.

154. See Id., p. 151, note 254. See also the New Catholic Encyclopedia (Palatine, Ill., 1981 reprint), vol. 9, pp. 972–973. Arguably, the Catholic chapels in Maryland were older. See Id., vol. 9, pp. 971–972, 1016.

155. See Southern Journal, p. 157.

156. Id., p. 151.

157. Id., p. 151.

158. See id., p. 158, n. 271.

159. Id., p. 158. Quincy, was, however, rude about the communion, referring to “nick nacks,” slang for appetizers. “We were not asked to come within the Communion, nor presented with a sight of the Nick nacks I had seen at a distance.” Id., p. 158.

160. Id., p. 152. See, on the Moravians, id., p. 150, n. 253. It was a “Christ-centered” worship, as Quincy noted.

161. See Wood, Franklin, supra, p. 69.

162. See Southern Journal, p. 166.

163. Id., p. 167.

164. See id., p. 167, n. 288.

165. Id., p. 165.

166. Id., p. 165.

167. Id., p. 145.

168. See Edmund S. Morgan, Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, 2002), pp. 15–22, 59. (Hereafter “Morgan, Franklin.”)

169. Id., p. 163.

170. Lambert, supra, p. 205. See also Finke and Stark, supra, pp. 22–53.

171. Lambert, supra, p. 206.

172. Beeman, supra, p. 94.

173. Id., p. 93.

174. Southern Journal, p. 111.

175. Id., pp. 134–135.

176. Id., p. 111.

177. Id., p. 163.

178. See Morgan, Franklin, supra, pp. 15–22, 59.

179. See Wood, Radicalism, p. 331.

180. Southern Journal, p. 151.

181. Wood, Radicalism, pp. 329–330.

182. See Southern Journal, pp. 86–87.

183. Adams observed, “Looking about me in the Country, I found the practice of Law was grasped into the hands of Deputy Sheriffs, Petty-foggers and even Constables … I mentioned these Things to some of the Gentlemen in Boston, who disapproved and even resented them very highly. I asked them whether some measurer might not be agreed upon at the Bar and sanctioned by the Court, which might remedy the Evil?” Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, L. H. Butterfield ed., Vol. III, p. 274. See, Daniel R. Coquillette, “Justinian in Brain-tree: John Adams, Civilian Learning, and Legal Elitism, 1758–1775,” Law in Colonial Massachusetts, pp. 359–418. (Hereafter, “Coquillette, Justinian in Braintree.”)

184. See Josiah Quincy, Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy (2d ed., Eliza L. Quincy, Boston, 1874), pp. 27–28. (Hereafter, “Memoir.”)

185. See John H. Langbein, “Blackstone, Litchfield, and Yale: The Founding of the Yale Law School,” in History of the Yale Law School (New Haven, 2004), pp. 23–32. (Hereafter, “Langbein.”)

186. Quincy’s legal training is discussed at length in the “The Legal Education of a Patriot: Josiah Quincy Jr.’s Law Commonplace,” Quincy Papers, vol. 2 (Hereafter “Introduction, Law Commonplace.”) His tutor, from 1763 to 1765, was Oxenbridge Thacher (1719–1765) “one of the most eminent lawyers of the period.” See Memoir, supra, pp. 6–7 and Appendix 6 to the Reports, Quincy Papers, vol. 5, for a brief biography. See also Langbein, supra, pp. 19–20; Charles R. McKindy, “The Lawyers as Apprentice: Legal Education in Eighteenth Century Massachusetts,” 28 J. Legal Educ. 124, 127–136 (1976) and Steve Sheppard, “Casebooks, Commentaries, and Curmudgeons,” 82 Iowa L. Rev. 547, 553–556 (1997).

187. See the “Introduction, Law Commonplace,” Quincy Papers, vol. 2. Thomas Jefferson had the benefit of legal training by George Wythe (1726–1806), but before Jefferson himself established a legal program at William and Mary in 1779, John Marshall was one of Wythe’s students there in 1780. Marshall only attended a brief course of lectures in that year. See generally Paul D. Carrington’s excellent “The Revolutionary Idea of University Legal Education,” 31 William and Mary L. Rev. 527 (1990).

188. See Reports, p. 317. “… I proceed (maugre any) at this court to manage all my own Business… though unsanitified and uninspired by the Pomp and Magic of the Long Robe.” Id.

189. See Reports, supra, Appendix 10, “Composition of the Superior Court of Judicature, 1745–1775.”

190. See Southern Journal, pp. 68–71, as to South Carolina, where the judges did not serve quam se bene gesserint (“as long as they shall behave themselves”).

191. See Reports, p. 215, pp. 265–272, p. 316. See Bernard Bailyn, The Ordeal of Thomas Hutchinson (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), pp. 117–118. (Hereafter, “Bailyn.”) Hutchinson was accused of “accumulating offices and functions totally incompatible with each other.” Id., p. 117.

192. See Quincy’s scathing comments on the lack of published statutes in South Carolina, Southern Journal, p. 61, and of “no laws in force” in North Carolina, id., p. 108 (emphasis in original).

193. Id., pp. 74, 77. These had been compiled by Edward Rutledge (1749–1800). Quincy’s copy remains in the Massachusetts Historical Society, Quincy Family Papers, No. 60 (Micro. Reel 4). See James Haw, John & Edward Rutledge of South Carolina (Athens, Georgia, 1997), pp. 19–21, 179.

194. Id., p. 119.

195. See Introduction, Law Commonplace, Quincy Papers, vol. 2. See also Reports, Quincy Papers, vol. 5, Appendix 9, “Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Estate of Josiah Quincy jun: Esq: Deceas’d.”

196. See Quincy’s emotional reaction, “I pray GOD give me better hearts,” to the looting of Chief Justice Hutchinson’s house. Reports, pp. 168–173.

197. See Southern Journal, pp. 56–61, 87–88.

198. Id., p. 57.

199. Id., p. 61, and accompanying notes.

200. Id., p. 61, and accompanying notes.

201. Id., p. 61, and accompanying notes.

202. William Simpson was “One of the assistant-judges of the Court of General Sessions of the Peace, Assize, etc., of the said Province.” See Morris L. Cohen, Bibliography of Early American Law (Buffalo, 1998), vol. III, p. 25, Item 8001.

203. Southern Journal, p. 61. Quincy may have been a bit unkind to South Carolina’s legal culture. In 1736 Nicholas Trott, “Chief Justice of the Province of South Carolina,” had published The Laws of the Province of South Carolina (Charleston, 1736), in two parts, including the “Two Charters granted by Charles II to the Lord Proprietors of South Carolina” and the Act of Parliament in which these proprietors surrendered “their Title and Interest to His Majesty.” Earlier, in 1721, Trott had published The Laws of the British Plantations in America Relating to the Church and the Clergy, Religion and Learning (London, 1731). But there was no regular publication of the statutory law, as in Massachusetts. See Daniel R. Coquillette, “Radical Lawmakers in Colonial Massachusetts: The ‘Countenance of Authoritie’ and the Lawes and Libertyes” 67 New England Quarterly (1994), p. 179 at pp. 194–206. Special thanks to Mark Sullivan.

204. Id., p. 61.

205. See J. H. Baker, An Introduction to English Legal History (4th ed., London, 2002), pp. 53–69. (Hereafter, “Baker.”) See also Daniel R. Coquillette, The Anglo-American Legal Heritage (2d ed., Durham, N.C., 2004), pp. 147–164. (Hereafter, “Coquillette.”)

206. See Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 2 “There shall be one form of action to be known as ‘civic action’.”

207. Southern Journal, p. 61.

208. Wood, Radicalism, supra, p. 72.

209. Id., p. 72.

210. See Daniel R. Coquillette, “First Flower—The Earliest American Law Reports and the Extraordinary Josiah Quincy, Jr. (1744–1775),” 30 Suffolk University Law Review (1996), pp. 1–34.

211. See Southern Journal, pp. 74, 77 and accompanying notes.

212. See Introduction, Law Commonplace.

213. See, for example, Dudley v. Dudley (1762), Reports, pp. 15–25; Banister v. Henderson (1765), Reports, pp. 130–155.

214. See the discussion in Bailyn, supra, pp. 49–51. Governor Bernard was correct in being able to “count on Hutchinson’s diligence in perfecting his knowledge of the law.” Id., p. 50. See Hanlon v. Thayer, Reports, p. 99, where Hutchinson admonished the lawyers for insufficient use of authority. Id., p. 102.

215. Southern Journal, p. 64. (Emphasis in the original.)

216. Id., p. 62.

217. Id., p. 65. A reference to John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, 1713–1799, see p. 182, n. 91, infra.

218. Id., p. 67.

219. Id., pp. 68–69. Quincy noted that two of the existing provincial judges had pushed the salary bill through the legislature, only to see their positions assigned to British placemen. “They are now knawing their tongues in rage.” Id., p. 73.

220. Id., pp. 68–69.

221. Id., p. 79.

222. See id., pp. 61, 71.

223. Id., p. 88. See also Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 57–77.

224. See Southern Journal, pp. 92–95.

225. Id., p. 94.

226. Id., p. 106.

227. Id., pp. 101–102.

228. Id., p. 116.

229. Id., p. 116, note 188.

230. Id., p. 108.

231. Id., pp. 111–112.

232. Id., p. 117.

233. Robert Stevens, Law School: Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill, 1983), p. 4. (Hereafter, “Stevens, Law School: Legal Education in America.”) See Paul D. Carrington’s excellent “The Revolutionary Idea of University Legal Education,” 31 William and Mary L. Rev. 527 (1990).

234. Id., p. 4.

235. Southern Journal, p. 118.

236. Id., p. 118.

237. Id., p. 119.

238. Id., p. 118.

239. Id., p. 119.

240. Id., p. 120.

241. See Coquillette, supra, pp. 183–188, 205–212, 311–325; Baker, supra, pp. 97–125.

242. For John Adams’s experience in the colonial vice-admiralty courts, see Coquillette, Justinian in Braintree, pp. 382–395.

243. Southern Journal, pp. 121–122.

244. See id., p. 121, and accompanying note.

245. Id., pp. 122–123.

246. Id., p. 123.

247. Id., pp. 123–124.

248. See Dudley v. Dudley (1762), Reports, p. 12 ff., and accompanying notes, and Baker v. Mattocks (1763), Reports, p. 69 ff., and accompanying notes. See also Earl Jowitt, The Dictionary of English Law (London, 1959), pp. 715–716.

249. See Baker, supra, p. 282; Coquillette, supra, pp. 113–114.

250. Southern Journal, p. 128.

251. Id., p. 138.

252. Id., p. 140.

253. Id., p. 147.

254. Id., p. 149.

255. Id., p. 162.

256. Id., p. 162.

257. Id., p. 162. Quincy did have a few rude words for another rival of Harvard, the “College” of Philadelphia. “To the South and North of this province we have much too exalted an idea of it.” Id., p. 149. This was to become the vestigial University of Pennsylvania, first chartered as an academy in 1751, and then as a college in 1765. In 1790, James Wilson would be appointed professor of law here, and would deliver his famous lectures from 1790–1791. See Stevens, Law School: Legal Education in America, pp. 11–12, n. 15, 15, n. 47.

258. Despite the distinction of Pennsylvania, we still know relatively little about its colonial legal system, at least compared to Massachusetts. As George L. Harkins observed in 1983, “[T]here have been few studies of the foundation of Pennsylvania’s legal system.” See George L. Harkins, “Influences of New England Law on the Middle Colonies,” 1 Law & Hist. Rev. 238 (1983), at 238, and sources cited. But there are exceptions. See, for example, Paul Lermack, “The Law of Recognizances in Colonial Pennsylvania,” 50 Temp. L. G. 475 (1977).

259. Southern Journal, p. 156. This was a blatant lie, as Quincy later recognized. Id., p. 156. See Morgan, Franklin, pp. 149–158.

260. Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (enlarged ed., Cambridge, Mass., 1992), p. 34. (Hereafter, “Bailyn, Ideological Origins.”) See also John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Stanford, 1959), pp. 144–145, 304 (“Whig gentry” as opposed to the radicals); Beeman, Radicalism, supra, pp. 95–109 (“Classical republican virtue”).

261. See York, “The Making of a Patriot,” Introduction, Quincy Papers, vol. 1.

262. Southern Journal, p. 155.

263. Id., p. 156.

264. Id., p. 155.

265. See Neil L. York, Turning the World Upside Down: The War of American Independence and the Problem of Empire (Westport, Conn., 2003), pp. 83–84, 87, 111–114. See also Neil L. York, “Federalism and the Failure of Imperial Reform, 1774–1775,” History, 86:282 (2001), 155, 160–164 (hereafter, “York, Federalism”); Bernhard Knollenberg, Growth of the American Revolution 1766–1775, pp. 81–211.

266. See Morgan, Franklin, pp. 145–188; Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, pp. 105–151. The political realities of the American Revolution dawned slowly on the British officials. See the excellent account in Stanley Weintraub’s recent Iron Tears: America’s Battle for Freedom, Britain’s Quagmire: 1775–1783 (New York, 2005). This book has led Gordon Wood to comment “[I]f history teaches anything, it teaches humility.” See Gordon S. Wood, “The Makings of a Disaster,” a review of the Weintraub book in The New York Review of Books, vol. 52, no. 7 (April 28, 2005), pp. 32–34.

267. York, Federalism, p. 170.

268. Id., p. 168.

269. Id., p. 172.

270. Id., p. 178, n. 91. As Neil York has also demonstrated, even the opposition Rockingham Whigs, such as William Dowdeswell, had great difficulty identifying with the colonists’ concerns. See Neil York, “William Dowdeswell and the American Crisis, 1763–1775.” 90 History (2005). 507, “Dowdeswell was the quintessential English country gentleman who could not truly empathize with protesting Americans.” Id., p. 507.

271. Southern Journal, pp. 96, 107.

272. Id., p. 104.

273. Id., pp. 53–54.

274. Id., p. 184.

275. Id., p. 18.

276. “Where little villains must submit to fate, The great ones may enjoy the World in state,” Sir Samuel Garth, The Dispensary: A Poem in Six Cantos (London, 1699), first canto. Many thanks to extraordinary diligence of Michael Hayden and Mark Sullivan in identifying this citation.

277. Southern Journal, pp. 18–19 (emphasis in original).

278. Id., pp. 19–20. See, on “enlightenment,” Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 146–147, 189–196.

279. Id., pp. 20–21.

280. Id., p. 21.

281. Id., pp. 21–22 (emphasis in original).

282. Id., p. 22.

283. Id., p. 22.

284. Id., p. 23.

285. Id., p. 23.

286. The London Journal, 1774–1775, supra, p. [248].

287. Id., p. [248].

288. Wood, Radicalism, supra, pp. 51–55.

289. Beeman, supra, pp. 147–151.

290. They offended Quincy, too. “In company were two of the late appointed assistant Justices from G[reat] B[retain]. Their behavior by no means abated my zeal against the British.” Southern Journal, p. 65.

291. Id., pp. 70–71.

292. Id., p. 46.

293. Id., pp. 53–54.

294. Id., p. 54.

295. Id., pp. 54–55.

296. See id., pp. 87–88. “Political enquiries and philosophie disputations are too laborious for them: they have no great passion to shine and blaze in the forums or Senate.” Id., p. 88.

297. Id., p. 55.

298. Id., pp. 55–56.

299. Id., p. 56.

300. Id., p. 78.

301. Id., p. 79.

302. See Beeman, supra, pp. 126–156.

303. Southern Journal, p. 89.

304. Id., p. 84.

305. Id., p. 86.

306. Id., pp. 85–86. (Emphasis in the orginal.)

307. Id., p. 86.

308. Id., p. 86.

309. Id., p. 86.

310. Id., pp. 87–88.

311. Id., pp. 84–85.

312. See VII, supra, “Laws and Lawyers,” Part B “North Carolina,” pp. 57–58, supra.

313. Southern Journal, p. 110.

314. Id., p. 110.

315. Id., p. 110.

316. Id., p. 111.

317. Id., p. 74 and extensive description of the “Regulators” in note 114.

318. Id., p. 107. Quincy used “sensible” to mean “convinced, persuaded.” See Johnson’s Dictionary, supra, n.p. “sensible.”

319. Southern Journal, p. 97.

320. Id., p. 96.

321. Id., pp. 96–97.

322. Id., p. 97.

323. See Beeman, supra, pp. 169–177.

324. “The profound alienation that typified these outbursts of violence in the Regulator movement had its payoff during the Revolution, when the eastern rulers of North and South Carolina society asked the back country settlers for their support during the Revolution.” Id., p. 176. The result was more violence, the “Uncivil War.” Id., pp. 176–177.

325. Id., p. 177.

326. Southern Journal, p. 116.

327. Id., p. 116. See Wood, Radicalism, pp. 68–69, on the reliance of gentry like Quincy on income from loans.

328. Southern Journal, p. 116.

329. Id., p. 116.

330. Southern Journal, p. 184.

331. Id., p. 184.

332. On the threat of slavery to the unity of the colonies, Quincy was a brilliant prophet. See the discussion at Section V, “Race and Slavery,” pp. 28–40, supra.

333. See Id., pp. 184–185 and accompanying notes.

334. Id., pp. 123–124.

335. These would be Southern Journal, pp. 125–126. See Editor’s Foreword, supra, and Transcriber’s Foreword, pp. 3–9, supra.

336. Southern Journal, pp. 121–122.

337. Id., p. 124.

338. Id., p. 127.

339. Id., pp. 121–122.

340. See Beeman, supra, p. 31.

341. Southern Journal, p. 130.

342. Id., p. 131.

343. Id., p. 141.

344. Id., pp. 134–135. See the discussion at Section VI, “Religion,” pp. 40–49, supra.

345. Southern Journal, p. 139.

346. Id., p. 140.

347. Id., pp. 138–139.

348. Id., p. 139. Derrick Lapp, Carroll’s biographer, described the struggle as follows:

“As the relationship between Great Britain and her North American colonies became more and more strained in the early 1770’s, events in Maryland would provide an opportunity for the Carrolls to re-enter the political stage. The lower house of the Maryland legislature began an investigation of the amount of revenue earned by proprietary officials by virtue of the office held. The high earnings revealed by this probe led the lower house to propose a reduction in fees, which, of course was rejected by the upper house. The ensuing ‘fee controversy’ pitted Daniel Dulany, the deputy secretary of Maryland (and one of the officials found garnering huge annual sums) against Charles Carroll of Carrollton, who took up the pen and the persona of ‘First Citizen’ to publish a series of essays in the Maryland Gazette. In their debate, ‘First Citizen’ and ‘Antilon’ (Daniel Dulany’s pseudonym) battled over the nature of government, the rights of Man, and the role of religious affiliation. In his first letter, which appeared on February 4, 1773, ‘First Citizen’ wrote: ‘Government was instituted for the general good, but Officers intrusted with its powers, have most commonly perverted them to the selfish views of avarice an ambition; hence the Country and court interests, which ought to be the same have been too often opposite, as must be acknowledged and lamented by every true friend of Liberty …’”

See Derrick Lapp, First Citizen Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland State Archive Online Publication, 2004), (hereafter, “Lapp”). See also Charles Carroll, Daniel Dulany, Maryland and the Empire, 1773; The Antilon – First Citizen Letters (Johns Hopkins, 1974); Dictionary of American Biography, V, p. 499.

The origin of the pseudonyms is interesting. According to the Dictionary of American Biography, Dulany

“on January 7, 1773, published a letter in defense of the government signed ‘Antilon,’ a pseudonym which it was generally understood concealed the identity of Daniel Dulany [q.v.]. This letter, in the form of a dialogue in which the arguments of ‘First Citizen’ against the government’s position were overcome by Dulany speaking as ‘Second Citizen,’ gave Carroll his opportunity. Dramatically enough he stepped into the clothes of the straw man Dulany had knocked down and under the signature of ‘First Citizen’ reopened the argument. The controversy was carried on in the Maryland Gazette until July 1, 1773, and when it was over Carroll had become indeed something like the First Citizen of the province.” Id., vol. III, p. 532.

Thus Dulany actually invented “First Citizen” as a straw man for argument, and Carroll adopted it for his use in a counterattack! But what about “Antillon”? According to Edward C. Papenfuse, Dulany “chose ‘Antilon’ which combines ‘anti’ and an old English word for unfair taxes [“Lon”].” “Remarks by Dr. Edward C. Papenfuse on the occasion of the presentation of First Citizen Awards to Senator Charles Smelser & Dr. William Richardson (Feb. 17, 1995), p. 1. http://www.mdarchives.state.md.us/msa/stagser/s1259/121/7047/html/ecpremar.html (hereafter, “Papenfuse”). See Oxford English Dictionary (2d ed., J. A. Simpson, E. S. C. Weiner, Oxford, 1989), Vol. VIII, p. 1120. (“lon” obs. forms of “loan”). This could possibly derive from the notorious forced “loans” of Charles I that resulted in the Five Knights’ Case of 1627 and the Petition of Right (1628). See Coquillette, supra, pp. 322–325. In any event, Dr. Papenfuse believed that Dulany “wanted to remind his readers that he had once eloquently defended them against the hated Stamp Tax.” Papenfuse, supra, p. 1. My special thanks to Mark C. Sullivan for this research.

349. Southern Journal, p. 140.

350. Id., p. 140.

351. See Id., p. 138, note 217. When Carroll died at age 91, he was the last surviving signer. According to Lapp:

Carroll of Carrollton would demonstrate himself to be a “true friend of Liberty” for nearly three decades. He served on the first Committee of Safety in Annapolis, and while Maryland wavered on the subject of pursuing independence, Carroll joined Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase in the effort to recruit Canada as a “fourteenth colony” in rebellion against England. As a Maryland delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Carroll served on the Board of War. He also helped to frame the Maryland constitution and would serve in the new state government as well as the Federal Congress as a U.S. Senator for Maryland. Lapp, supra.

352. Southern Journal, p. 138.

353. Id., p. 139.

354. See the discussion at Section III, “Gentility,” pp. 18–21, supra.

355. Southern Journal, p. 142.

356. Id., p. 143.

357. Id., p. 148, and accompanying notes.

358. Id., pp. 149–150, and accompanying notes.

359. Id., p. 148, and accompanying notes.

360. Id., pp. 149–150, and accompanying notes.

361. Id., p. 149.

362. Id., pp. 155–156.

363. See Morgan, Franklin, pp. 49–70; Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin, pp. 17–60; Walter Isaacson, Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (New York, 2004), pp. 146–174.

364. Id., p. 168.

365. Id., p. 161.

366. Id., p. 162.

367. See Morgan, supra, pp. 100–103, 114–115.

368. Southern Journal, p. 164.

369. Id., pp. 164–165.

370. Id., p. 165.

371. Id., p. 165.

372. Id., p. 165.

373. Id., p. 165.

374. According to Morgan, “what rankled most, at least to Franklin, was the interposition of the proprietary power between George II and his Pennsylvanian subjects … ‘the Proprietaries claiming that invidious and odious Distinction, of being exempted from the Common Burdens of their Fellow subjects.’” Morgan, Franklin, supra, pp. 100–101.

375. Southern Journal, supra, pp. 184–185.

376. Id., p. 166.

377. Id., p. 166.

378. Id., p. 168.

379. Id., p. 171.

380. See Editors’ Foreword to the Quincy Papers, Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. xvii–xxvii.

381. Southern Journal, p. 116.

382. Id., p. 134.

383. Id., p. 139.

384. Id., p. 91.

385. Id., p. 86.

386. Id., p. 88.

387. Id., p. 85.

388. For this insight into the latest academic controversies, I am grateful to my dear friend and colleague, Charles Donahue. See his masterful Washington and Lee Lecture of 2004, “Why and Whither Legal History?” pp. 2–9 [unpublished MS]. Quincy’s Southern Journal also fits neatly into two other current trends, “micro-history” and “prosopography,” both focusing on detail and the individual as tools for comprehending complex developments. “Prosopography” derives from the Greek “prosopan,” or “face” and refers to “a description of a person’s appearance, personality, social and family connections, career, etc.” The Concise Oxford Dictionary (8th ed., R. E. Allen, ed., Oxford, 1990), p. 959.

389. See Introduction, Law Commonplace, Quincy Papers, vol. 2.

390. Southern Voyage, p. 184.

391. See York, “The Making of a Patriot,” Part I, “A Life Cut Short,” Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. 32–35.

392. See The London Journal (1774–1775), vol. 1, pp. 267–269.

1. A reference to Quincy’s wife Abigail, the daughter of William Phillips of Boston. They married in 1769. She was referred to in Quincy’s journals as “E …” or “Eugenia,” as Howe observed “according to the affectations of the day.” Mark DeWolf Howe, Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, vol. 50 (October 1916 – June 1917), p. 434, n. 3. (Hereafter, “Howe, Proceedings, 1916‒1917.”) Howe was the editor of this journal in its first, and only, publication before this newly edited version, which is obviously indebted to his efforts. See Neil York’s tribute to Howe in the appendix to the Political Commonplace Book, Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. 219–221. Howe’s notes are integrated into this edition, as noted, with amendments.

2. Alexander Pope (1688‒1744), poet. Quotation from Pope’s An Essay on Man (London, 1733), Epistle 1, 1.13. Quincy owned all of the Pope’s works at his death. See Reports, Appendix 9, item 312 (“Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Estate of Josiah Quincy, Jun:Esq Decease’d). (Hereafter, “Quincy, Estate Catalogue.”)

3. Zoroaster: Prophet of ancient Iran in the latter half of the seventh century before the Christian era; the period of his activity falls between the closing years of Median rule and the rising wave of Persian power. Forerunner of Confucius, Zoroaster was a Magian, a.k.a. the famed Magi. The Persian wars brought Rome into contact with Zoroastrian. A.V. William Jackson, Zoroaster, The Prophet of Ancient Iran (London: MacMillan Co., 1899), pp. 140‒142.

4. “One of the last remaining uses for sailing ships was transoceanic mail delivery. Called packet boats after the British nickname for the mail dispatch, mail ships were built for speed. They carried mail to overseas locations, usually under the control of the home country.” Such ships usually offered the fastest and cheapest oceanic fares. Ships, Encarta Encyclopedia. Microsoft, Inc. 2002.

5. Howe, Proceedings, 1915‒1916 [fn 427-2]. Capt. Skimmer was killed in an engagement with a letter of marque brig in August 1778.

6. Virgil, Eclogue I: “We have left our country’s borders and sweet fields.”

7. Quincy’s father’s mansion stood in what was then Braintree, now Quincy. Completed in 1770, it would have been visible from the channel leaving Boston. See Illustration 1. Quincy’s father lived there until his death in 1784, at which point it was inherited by his grandson, Quincy’s son, Josiah “the Mayor.” See Neil L. York, “A Life Cut Short,” Introduction, Quincy Papers, vol. 1, pp. 15–46.

8. Virgil, Eclogue I: “You, Tityrus, calm in the shade.”

9. Virgil. “In his Eclogues he added a new level of meaning to the pastoral’s idealization of country life …” The Oxford Companion to English Literature (5th ed., M. Drabble ed.), 1031. (Hereafter, “Drabble.”) See Quincy, Estate Catalogue, p. 3, item 118, “Virgil.”

illustration 1. Map of Boston Harbor (London, c. 1775). Courtesy, Library of Congress, American Memory Collection. The Quincy homestead in Braintree is indicated in the lower, middle left (circled). The shipping channel would have been in sight above. See p. 89, Southern Journal, p. 3, “my father’s cottage.”

10. The Helicon was the largest mountain of Boeotia, a legendary mount of the muses. The fountain supplied by the mountain’s streams “were believed to inspire those who drank from them.” The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature (2nd ed., M. C. Howatson, ed.), p. 264. (Hereafter, “Howatson.”) “A draught from Helicon could once inspire / The bard to wing in song his loftiest flight; But poets of these later times require / A draft from Wall Street, payable at sight.” By Anne C. Lynch: Poems, 1852. Epigram.

11. Translation: “To me as great Apollo.” From Virgil, Eclogue III.

12. Yorick: Pseudonym of Laurence Sterne (1713‒1768), whose nine volumes of Tristam Shandy, published between 1760‒1768, were the most popular literary productions of England during the 1760s. “The book was read enthusiastically at Sterne’s own university, Cambridge, [where] a group at the university signed a mock deposition, stating that it contained the ‘best & truest & most genuine original & new Humour, ridicule, satire, good sense, good nonsense’ ever published.” Alan B. Howes, Yorick and the Critics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1958), pp. 2, n. 7; 5, n. 7. The pseudonym was probably inspired by the King’s jester whose skull was dug up in Shakespeare’s Hamlet (v. 1). See Drabble, supra, 7.

13. Howe, Proceedings, 1915‒1916 [fn 428-2]. Joseph Trapp (1679‒1747), poet and pamphleteer, Dictionary of National Biography, LVII, 155.

14. Howe, Proceedings, 1915‒1916 [fn 428-3]. By Abel Evans (1679‒1737). The epigram usually reads: “Keep the commandments, Trapp, and go no further, For it is written, that thou shalt not murther.”

15. Almost certainly the Boston Light on Little Brewster Island at the harbor’s entrance. The first light was built in 1716, and greatly improved after a fire in 1751. See Illustration 2, showing the Light as Quincy would have known it. It was damaged by both American and British troops during the Revolution and was replaced in 1783. See S. R. Snowman and J. G. Thomson, Boston Light: An Historical Perspective (Plymouth, Mass., 1999), pp. 7‒14.

16. A solution. Apparently a sea sickness remedy. See Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (concise edition, London, 1756), n.p. “diluter.” (Hereafter, “Johnson, Dictionary.”) I have chosen this edition of Johnson’s dictionary as the one more likely to be available to American colonists than the massive unabridged version. “Samuel Johnson’s dictionary, as well as his theory of language … remains an invaluable guide to what our founders had in mind when they set the democratic experiment in motion.” Jack Lynch, “Dr. Johnson’s Revolution,” New York Times (July 3, 2005), p. A-27.

illustration 2. Boston Light was “the first modern-style lighthouse in the New World.” As Quincy saw it, it would have been rebuilt as of 1751. See Mapping Boston (eds. A. Krieger, D. Cobb, A. Turner, Cambridge, Mass., 1999), p. 104. This view was based on a rendition of William Burgis in 1729, pictured on the front of Massachusetts Magazine, February 1789, just after the light was rebuilt in 1783. (Courtesy, Library of Congress.) See S. R. Snowman, J. G. Thomson, Boston Light: A Historical Perspective (Plymouth, Mass., 1999), p. 9. Many thanks to my Editorial Assistant, Patricia Tarabelsi. See p. 95, Southern Journal, p. 6, “reached the Light house.”

17. From Euclid’s Elements (c. 300 b.c.). See Howatson, supra, 223–224.

18. John Gay (1685–1732), poet and dramatist. Gay’s first series of ‘Fables’ was issued in 1727; the second series, his principal posthumous work, was issued in 1736. It is in this posthumous edition that the fable of “The Cook-maid, the Turnspit and the Ox” first appears. See Gay, Fables, pp. 228–232. The gist of the fable is the cook-maid envys her masters, the dog kept to turn the roasting-spit by running on a treadmill, i.e. “the turnspit,” envys the cook-maid, but neither is as badly off as the ox on the spit. “Let envy then no man torment: think on the ox, and learn content.” Id. Gay was among the main representatives of burlesque comedy in the 18th century, “[w]ith his famous Beggar’s Opera (1728) he produced one of the funniest and most original stage works of the age.” Michel-Michot, Paulette, Marc Delrez, and Christine Pagnoulle, History of English Literature, 2d part, 1660–1840 (University of Liege, Belgium, unpublished). See Drabble, supra, pp. 384–385. Gay composed his own epitaph for his memorial in Westminster Abbey. “Life is a jest, and all things show it. I thought so once and now I know it.” Id., p. 383. Special thanks to Mark Sullivan.

19. [Binnacle]: a housing for a ship’s compass and a lamp. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition.

20. The Boston Light. See Illustrations 1 and 2, supra.

21. “Justice” is crossed out in the manuscript. Quincy is referring to his law practice before the Massachusetts Superior Court. Johnson defines “jar” as “[c]lash; discord; debate.” Johnson, Dictionary, supra, n.p. “jar.”

22. Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916 [fn 430-1]. From William Shakespeare, The Tempest. “[P]robably written in 1611, when it was performed before the King in Whitehall.” Drabble, p. 968. The first line reads, “The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch.” Act 1, scene 2. See p. 179, infra.

23. [Hussar:] a member of any of various European units originally modeled on the Hungarian light cavalry of the 15th century. Also used to describe “jacket” or “waistcoat” as in “hussar jacket.” See The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary (Oxford, 1971), vol. 1, p. 1353. (Hereafter, “Oxford English Dictionary.”) [Surtout:] a man’s long close-fitting overcoat. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition.

24. See note 12, supra.

25. For an account of John Alexander Hunter, see “Introduction,” Southern Journal, supra, at Section VIII, A., “Hunter, the Dishonest Purser,” pp. 64–66.

The quotation comes from a satirical poem by Sir Samuel Garth (1661–1719), a distinguished physician and friend of Alexander Pope, written to ridicule the opposition of the London apothecaries to a charitable dispensary established by the College of Physicians that gave free drugs to the poor. See Drabble, supra, pp. 381–382. The poem, in its final corrected version, was published by John Nutt as The Dispensary: A Poem in Six Cantos (2nd ed., London, 1699). The relevant verses read as follows:

Not far from that most celebrated place [the Old Bailey],

Where angry Justice shows her awful face;

Where little villains must submit to fate,

That great ones may enjoy the world in state;

There stands a dome [the Dispensary], majestic to the sight,

And sumptuous arches bear its oval height;

A golden globe, placed high with artful skill,

Seems, to the distant sight, a gilded pill:

This pile was, by the pious patron’s aim,

Raised for a use as noble as its frame.

Id., pp. 1–2. As always, my gratitude to Mark Sullivan, superb reference librarian.

26. [“Belles Lettres”] “Writings on studies of a literary nature …” The Concise Oxford Dictionary (Ed. R. E. Allen, 8th ed., Oxford, 1990), p. 101. (Hereafter, Concise Oxford Dictionary.) “Severer studies” are advanced studies, such as law.

27. Admiral John Montagu (1719–1795), commander-in-chief on the North American station, 1771–1774. See Dictionary of National Biography, XXXVIII, 258. See also Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916 [fn 434-1].

28. Approximate Currency Equivalencies: £45 Sterling = $45,000 (2004); £300 Sterling = $300,000 (2004); £400 = $400,000 (2004). In a freewheeling way, I have arrived at these values by comparing costs of contemporary commodities, including books and hogsheads of wine. See pages 77 and 119, infra. Other comparative costs are to be found at pp. 44, 53, 61, 67, 71, 76–78, 82, and 119, infra. For example, Longfellow House on Brattle Street in Cambridge sold in 1781 for $4,264. Modern houses of comparable size and desirability sell for about $4 to $5 million. The same ratio is true of most commodities mentioned by Quincy. While the ratios are higher than those usually employed, I believe they are more realistic. See John J. McCusker, “How Much is that in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for use as a Deflation of Money Value in the Economy of the United States,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, vol. 101, pl. 2 (Worcester, 1992), 297–373. See also John J. McCusker, Money and Exchange in Europe and America 1600–1775: A Handbook (Chapel Hill, 1978); Leslie V. Brock, “Colonial Currency, Prices and Exchange Rates,” 34 Essays in History (1992), 70–132, set out at http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/users/brock. Most importantly, these values make intuitive sense in comparing our world with Quincy’s. Many thanks for the assistance of Patricia Tarabelsi with this note.

29. Bermuda is located at 32.20 N and 64.45 W. This was particularly significant to Quincy, whose brother Edmund (1733–1768) was lost by shipwreck in these latitudes. See note 35, infra.

30. [Bowsprit:] a large spar projecting forward from the stem of a ship. Merriam Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Tenth Edition.

31. Shakespeare, Tempest (Act I, Scene 2, ll. 201–203). The line reads: “Not a soul but felt a fever of the mad and play’d some tricks of desperation.”

32. John Milton’s 1634 play, Comus (l. 343). “Cynosure,” “[t]he star near the north pole, by which sailors steer.” Johnson, Dictionary, supra, n.p. “cynosure.”

33. Alexander Pope, Essay on Man, 1733 (ep. I, l. 157). Ammon was an Egyptian god with the head of a ram. Howatson, supra, pp. 31‒32.

34. Howe, Proceedings, 1915‒1916 [fn 436-1]. Edmund Quincy (1733‒1768). See note 29, supra.

35. Howe, Proceedings, 1915‒1916 [fn 436-2]. John Apthorp married, December 12, 1765, Hannah, daughter of Stephen Greenleaf.

36. Alexander Pope, Essay on Man, 1733, (ep. I, ll. 17‒28).

37. John Milton’s 1634 play, Comus (l. 362).

38. William Shakespeare’s 1602 play, Hamlet (Act III, sc. 1, line 87ff.) reads “But that the dread of something after death, The undiscover’d country from whose bourn, No traveler returns …”. John Milton’s 1634 play, Comus (l. 597), reads: “The pillar’d firmament is rottenness, And earth’s base built on stubble.” Quincy was a very literate young man!

39. Shakespeare, Macbeth (soliloquy) Act 5, Scene 5, ll. 19–28. The last line has been altered by Quincy from “The way to dusty death” to a more optimistic “The way to study wisdom”! He also omitted “from day to day” in the second line, but, if from memory, it was quite an accurate recollection.

40. With no opportunity to make lunar or solar observations, the longitude of the ship would be unknown. A chronometer would have been most unlikely on Quincy’s ship in 1773. Although invented by John Harrison (1693–1776) in 1759 and used by Captain Cook in his voyages between 1772 and 1776, chronometers were not widely deployed on commercial ships until much later. See Rupert T. Gould, The Marine Chronometer: Its History and Development (London, 1923), pp. 40–70. Thus, the ship could be as far west as the Carolina barrier beaches, or as far east as the Bahama shores. Latitude was an easier matter, if sightings of the polar star, or “cynosure,” were possible, and Quincy remarks that they were “in the latitude of Bermudas”; (32.20 N) and in the latitude where his elder brother died. See pp. 24, 29. Latitude could be determined by the height of the polar star above the horizon.

41. True hurricanes, being swirling winds circling about an “eye,” would appear to have a calm, and then winds from exactly the opposite direction. But such storms tend to occur in the late summer or fall in these latitudes.

42. An attached newspaper clipping reads: “From an English Print of the 3d of March, which we are favored with by one of the Passengers, we find that on the 26th and 27th of February they had in England a prodigious high Wind, or rather Hurricane, by which great Damage was done in London and other Places, by blowing down Houses, Chimnies, etc. and to the Shipping in the River, as almost every Vessell from Greenwich to London Bridge, were drove from their Moorings; and by running foul of each other several of the smaller ones were sunk, and many Lives lost; others dismasted, and some drove ashore; among the latter were the Ships Earl of Dunmore, and Dutchess of Gordon, in the New-York Trade: Great Damage was likewise done at Cowes, Portsmouth, Downs, and other Seaport Places, the ‘Elements (as the Paper says) seemed to be all over in a Ferment, and the Clouds appeared of a fiery Red for many Hours:’ Capt. Hall, of this Place, in a Ship just arrived in the Downs from Dartmouth, was drove ashore off Kingsdown, and lost her Rudder and received other Damage.” See Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916 [fn 138-1].

43. “Necessity, who is the mother of invention.” Plato, The Republic, Book I, 344 (c), Jowitt translation.

44. “What sorrow was, thou bad’st her know, And from her own she learn’d to melt at others’ woe.” Thomas Gray (1716–1771), Hymn to Adversity (1742) stanza 2, lines 15–16.

45. Ode to Adversity (1753) by Thomas Gray (1716–1771), author of “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard” (1751), is among the most celebrated, and most quoted, poems of the 18th century.

46. See Illustration 3. Charleston, situated on neck of land between Ashley and Cowper rivers; in 1787 contained about 800 houses. Lat. 42.10.N. Long. 72.15.W. The American Gazetteer, Containing a Distinct Account of all the Parts of the New World, printed for A. Millar and J. & R. Tonson, 1762. 1787—15,000 inhabitants, including 5400 slaves. Jedidiah Morse, D.D., The American Gazetteer. Printed in Boston, 1797.

47. See Illustration 4.

illustration 3. Charleston Harbor in 1742. From the collections of the South Carolina Historical Society. Courtesy, South Carolina Historical Society.

48. Levinus Clarkson (1740–1798). Born in Jamaica, Long Island. Married Mary Ann Van Horne and had 10 children. The Sawyer Family History, www.sawyer-family.org, 2000. Clarkson was an active patriot and apparently had business with the Secret Committee of the Continental Congress, as evidenced by the following record:

THURSDAY, JULY 10, 1777: A petition from Joseph Belton, and a petition from Captain James [Joseph] Lees, were read: 11 The petition of Joseph Belton is in the Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 42, I, folio 137. Ordered, That the petition of J. Belton be referred to the Board of War, and the petition of Captain Lees to the Marine Committee. The Secret Committee laid before Congress a letter of the 8 June last, from John Dorsius, for self and Levinus Clarkson, and a bill of exchange, drawn by Alexander Ross on John Dorsius, in favour of Willing, Morris & Co. Ordered, That the same be referred to the Board of Treasury, in order to bring in a report for paying the before mentioned bill here, and directing Mr. Dersius to apply the amount of the said bill in discharge of the debts incurred in consequence of orders from the Secret Committee, and also to enable the agents of the Secret Committee 0170 543 in South Carolina, to receive all the money arising from the sale of the State lottery tickets in that State, towards discharging the debts aforesaid. Library of Congress: Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789. Edited from the original records in the Library of Congress by Worthington Chauncy Ford, Chief, Division of Manuscripts, Volume VIII. 1777: http://memory.loc.gov/ll/lljc/008/lljc008.sgm_old

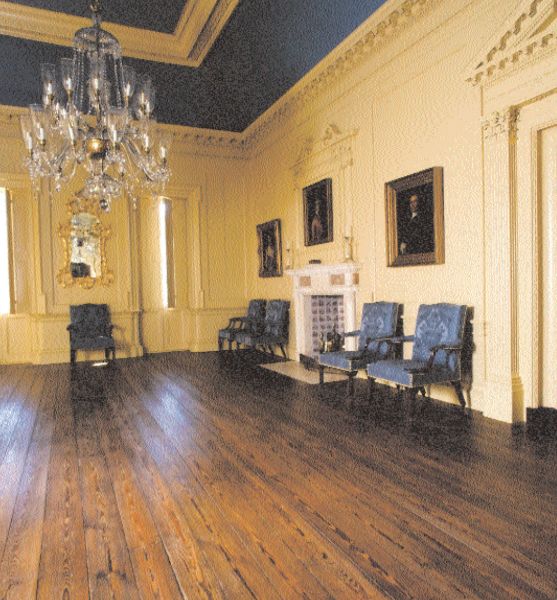

illustration 4. The Exchange Building, Charleston. The core of the building, built in 1767–1771, would be identical to the one Quincy saw. Courtesy, Library of Congress. Date, circa 1865. See p. 138, Southern Journal, p. 41, “the New Exchange.”

49. Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916 [fn 441-1]. David Deas (d. 1775), treasurer of the Chamber of Commerce of Charleston, December 1773.

50. Howe, Proceedings, 1915–1916 [fn 441-2]. Mention of this Society is found in the South Carolina Gazette, November 30, 1767. From 1766–1771, concerts were held in Charleston’s most prominent public-house, or tavern, located on the north-east corner of Broad and Church Streets; sometimes referred to as “the Corner.” Votaries of Apollo: The St. Cecelia Society and Concert Music in Charleston, South Carolina, 1766–1820 (Indiana University Dissertation [2003] by Nicholas Michael Butler, unpublished, pp. 186–190).