THE LATIN LEGAL MAXIMS OF JOSIAH QUINCY JR.

151

vid vol. 3 p. 161.1

vid. p. 101 of this Book

Maxims of the Civil Law2

[1]+ In ambiguis orationibus maxime sententia spectanda est, qui eas protulisset. l. 96. ff. De Reg. Jur.3

[2] Benignius Leges interpretendae sunt: quo voluntas4 Earum conservetur. l. 18 ff De Legib.

[3] Scire Leges non hoc est verba Earum tenere, sed vim, ac Potestatem. Ibid. 17. ff. De Legib.

[4] Etsi maxime verba Legis hunc habet Intellectum, tamen Mens Legislatoris Aliud vult. L. 13. p 2. ff. De excustut5

[5] Quod quidem perquam durum est:6 sed ita Lex scripta est. l. 12. p.1. ff qui & a quib.

[6] Placuit in Omnibus Rebus praecipuam esse, Justitiae, Aequitatisq:, quam Stricti Juris Rationem. l. 9. c. De Judic.7

[7] Haec Aequitas Suggerit, etsi Jure deficiamur. l. 2 p. 5. in f. ff De Aqua & aquae Pluv. arc. [8] Benigniorem Interpretationem sequi, non minus8

+This indefinite Rule9 appears to be general & common to all Matters10: And if apply’d to all indifferently, we must conclude that in Contracts as well as Testaments, an ambiguous Expression must be interpreted by the Intention of Him whose Will it was to declare. And yet this Application, wch will always be just11 in Testaments, will often be found false in Contracts: For in Testaments one only speaks, & his will is to serve for a Law; but in Contracts the Intention both of the One & the Other is the Common Law. Thus the Intention of12

Maxims of the Civil Law

see vid vol. 3 p. 161.

see. p. 101 of this Book

[1] +With regard to ambiguous remarks, the intention of the one who proffered them must be considered above all else.1

[2] Laws must be interpreted liberally so that their will is preserved.2

[3] To know the laws is not to grasp their words but rather their force and power.3

[4] Even though the words of the law (i.e., a literal reading) have always had this meaning, nevertheless the legislator’s intent wills a different interpretation.4

[5] Indeed it is extremely strict, but thus has the law been written.5

[6] It was decided that, in all things, justice and equity are to be foremost, rather than the rule of strict law.6

[7] Equity suggests these things, even though we are failed by the law.7

[8] To follow the more liberal interpretation is no less just than safe.8

+This indefinite rule appears to be general and common to all matters. And if applied to all indifferently, we must conclude that in contracts as well as testaments, an ambiguous expression must be interpreted by the intention of him whose will it was to declare. And yet this application, which will always be justice. Testaments will often be found false in contracts. For in testaments one only speaks, and his will is to serve for a law. But in contracts the intention both of the one and the other is the common law. Thus the intention of

Thomas Woods, A New Institute of the Imperial or Civil Law (2nd ed., London, 1712). See pages 340, 342, note 3; Maxwell, p. 613. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School.

Civ. L. Maxims

minus justius est quam tutius. l.191. p.1 ff De Reg. Jur.

[1] Semper in Dubiis benigniora praeferenda sunt. l. 56. eod.1

[2] Rapienda Occasio est quae praebet benignius Responsum. l. 168. Eod.2 ⊗

[3] In ambigua voce3 Legis ea potius accipienda est Significatio quae vitio caret, praesertim, cum etiam voluntas Legis ex hoc colligi possit: l. 19. ff De Legib.

[4] Quoties4 Idem Sermo duas Sententias exprimit, ea potissimum accipiatur5 quae rei gerendae aptior est. l. 67. ff De Reg. Jur.

[5] Incivile est nisi totâ Lege perspecta, una aliquâ Particulâ ejus propositâ, judicare, vel respondere. l. 24. ff De Legib.

[6] Nulla Juris Ratio, aut Aequitatis Benignitas patitur, ut quae Salubriter pro Utilitate Hominum introducuntur, ea nos duriore Interpretatione contra Ipsorum commodum producamus ad Severitatem. l. 25. ff De Legib.

of One ought to answer6 to that of the Other, & they must understand One Another, & agree together, & according to this Principle it often happens, that an ambiguous Clause is not to be interpreted by the Intention of him who expresses it, but rather by the reasonable Intention of the Other. Thus etc. Wood. Civ. Law. p. 58.7

⊗ It cannot be fix’d as a general Rule,8 that the Rigour of the Law shd9 always be follow’d against the Mitigations of Equity, or that we shd always recede from the Rigour. Ibid. 72. But we must judge by the Rigour of the Law, if the Law will not admit of any mitigation, or by an equitable Mitigation, if the Law will admit of it. Ibid.10 Although11

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] The more liberal interpretation should always be preferred in doubtful situations.1

[2] The occasion which offers a favorable response must be seized.⊗2

[3] In an ambiguous statement of law, that meaning which is without fault should be accepted, especially when the will of the law can also be deduced from this.3

[4] As often as the same remark expresses two meanings, that one is to be accepted above all which is more suited to the management of the matter.4

[5] Unless the whole law is examined, it is improper to judge or to respond to any part of its propositions.5

[6] No reckoning of the law or kindness of equity is allowed when, just as something is introduced advantageously for the benefit of men, we bring forth (a result) contrary to these very advantages, through a harsh interpretation tending toward severity.6

of one ought to answer to that of the other, and they must understand one another; and agree together, and according to this principle it often happens that an ambiguous clause is not to be interpreted by the intention of him who expresses it, but rather by the reasonable intention of the other. Thus etc.7

⊗It cannot be fixed as a general rule that the rigor of the law should always be followed against the mitigations of equity, or that we should always recede from the rigor. Ibid. 72. But we must judge by the rigor of the law if the law will not admit of any mitigation or by an equitable mitigation if the law will admit of it. Ibid. Although8

This is Arnold Vinnius’s commentary on Justinian’s Institutes. See “Introduction,” supra, pp. 31–32. See also John Adams’s diary for Sunday, October 5th, 1758. John Adams, Diary, vol. 1 (L. H. Butterfield, ed., 1964), pp. 44–46. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School. See Coquillette, Anglo-American Legal Heritage, supra, p. 34.

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] In levioribus Causis proniores ad Lenitatem, Judices esse debent; in Gravioribus Paenis1 Severitatatem Legum cum aliquo Temperamento Benignitatis subsequi.2

[2] Non omnium, quae a majoribus nostris constituta sunt, Ratio reddi potest. D.1.3.20.

[3] Multa in Jure communi contra Rationem disputandi pro Utilitate communi recepta sunt.3 D.9.2.51.2.

[4] Quod contra Rationem Juris receptum est non producendum4 ad Consequentias. D.50.17.141.etc.

[5] Minime sunt mutanda quae Interpretationem certam semper habuerunt. D.1.3.23

[6] Quicquid5 in Calore Iracundiae vel fit vel dicitur non prius ratum est quam si Perseverantia apparet6 Judicium Animi fuisse. D.50.17.48.

Although the Rigour of the Law seems to be distinguish’d from Equity, & they appear to be even opposite to one another, yet ’tis always true, that in such Cases wherein this Rigour is to be follow’d, another Consideration of Equity makes it just. And is7 it can never happen that what is equitable is contrary to Justice, so neither can it happen, that what is just is contrary to Equity. Thus etc. W.civ.Law. 72.

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] In less serious cases, judges should be inclined toward leniency; with more serious punishments, the harshness of the laws is to be followed with some measure of kindness.1

[2] A reason cannot be given for everything that was established by our ancestors.2

[3] Many things contrary to logical argument were received into the common law for the common good.3

[4] That which was received against the reason of the law should not be extended to subsequent cases.4

[5] Matters that have always had a certain interpretation should be changed as little as possible.5

[6] Whatever happens or is said in the heat of anger was not thought out first even if it appeared from perseverance to be a reasoned judgment.6

Although the rigor of the law seems to be distinguished from equity, and they appear to be even opposite to one another, yet it is always true that in such cases wherein this rigor is to be followed, another consideration of equity makes it just. And as it can never happen that what is equitable is contrary to justice, so neither can it happen that what is just is contrary to equity. Thus etc.7

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] Ratum non habetur1 quod non bona fide gestum est. C.4.44.1.2

[2] Quae in Testamento scripta essent, neque intelligerentur quid significarent,3 ea perinde sunt ac si scripta non essent. D.34.8.2.

[3] Voluntas facit quod in Testamento scriptum valet.4 D.30.1.12.3.

[4] Cum in Testamento ambigue aut etiam perperam scriptum est, benigne interpretari & secundum id5 id quod credibile est cogitatum, credendum est. D.34.5.24.

[5] Non aliter a Significatione Verborum recedi oportet quam cum manifestum est aliud sensisse Testatorem. D.30.1.4.

[6] Haeredi magis parcendum est. D.31.1.47.6

[7] Uniuscuiusq. Contractus Initium spectandum est, & Causa.7 D.17.1.8

[8] Cujusq8 Rei potissima Pars Principium est. D.1.2.1.

[9] In Obscuris inspici solere quod verisimilius est, aut quod plerumque fieri solet. D.50.17.114.

[10] In Conventionibus Contrahentium voluntatem potius quam verba spectari placuit. D.50.16.219.

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] That which was not done in good faith will not be upheld.1

[2] Those things which have been written in a testament, and yet it is not understood what they mean, are just as if they had never been written.2

[3] The will makes that which is written in a testament have strength.3

[4] When in a testament something was written ambiguously or even incorrectly, it is to be interpreted liberally and according to that which is the likely intent, which must be given credence.4

[5] We should not otherwise depart from the meaning of words than when it is clear that the testator intended something else.5

[6] One should act sparingly toward an heir to a greater degree.6

[7] The beginning of every single contract should be examined, as well as its inducement.7

[8] The most important part of everything is the beginning.8

[9] In obscure matters, it is customary to consider what is probable, or what is most likely to occur.9

[10] In agreements it is resolved that the will, rather than the words, of the contracting parties is to be observed.10

Justinian, Corpus Juris Civilis, Amsterdam, 1681, containing the Digest. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School. Continental editions of this type were regularly found in colonial libraries. See, for example, The Printed Catalogues of the Harvard College Library (W. H. Bond, H. Amory, eds., Boston, 1996), pp. A9, A10, A19 (1723 Catalogue); p. B15 (1773 Catalogue).

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] Non videntur, qui errant, consentire. D.50.17.116.2.

[2] Nemo videtur fraudare eos qui sciunt & consentiunt. D.50.17.145.

[3] Qui cum alio contrahit vel est, vel esse debet,1 non ignarus Conditionis ejus. D.50.17.19.

[4] In pretio Emptionis & venditionis naturaliter licet2 contrahentibus se circumvenire. D.4.4.16.4.

[5] Fraudis Interpretatio semper in Jure Civili non ex Eventu duntaxat, sed ex Consilio3 quoque Consideratur.4

⊗[6] Res tanti valet, quanti vendi potest.5 D.36.1.1.16.

[7] Non exemplis sed Legibus judicandum.6 C.7.45.13

[8] Satius est impunitum7 relinqui Facinus nocentis, quam Innocentem damnari. D.48.19.5

[9] In Maleficiis Voluntas spectator non Exitus. D.48.8.14.

[10] In Maleficiis Ratihabitio mandato aequiparatur.8 D.50.17.152.1. Interpretatione

⊗It must not be consider’d, what has been done, or what is done, but what ought to be done. W.Civ.Law. B.4 Ch. 1. p. 295

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] Those who err are not seen to consent.1

[2] No one is perceived to defraud those who understand and consent.2

[3] One who contracts with another is not, or should not be, ignorant of his terms.3

[4] With regard to the price, in buying and selling, it is naturally permitted to the contracting parties to overreach each other.4

[5] In the civil law an explanation of fraud is always examined not only from the outcome but also from the intention.5

⊗[6] A thing is worth as much as it is possible to be sold for.6

[7] One must judge not from examples but from laws.7

[8] It is better that a harmful deed8 remain unpunished than an innocent person be convicted.9

[9] With regard to crimes, the will,10 not the result, is to be examined.11

[10] With regard to crimes, acquiescence is to be equated with a command.12

⊗It must not be considered, what has been done, or what is done, but what ought to be done.13

This is the Frontispiece of Arnoldus Vinnius (1588‒1657) Partitionum Juris Civilis Libri IV (Rotterdam, 1664). The figure on the left represents the Emperor Justinian. On the right is a modern sovereign, possibly the Holy Roman Emperor. Below is a picture of the modern sovereign with his legal counselors, his judges or jurists. Note this Roman law treatise was published in Holland in 1664. The Dutch still have a civil law system. South Africa, a former Dutch colony, has been remarkably influenced by Roman law. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School. See Coquillette, Anglo-American Legal Heritage, supra, p. 12.

Civ. L. Maxims1

[1] Interpretatione Legum Paenae Moliendae sunt, potius quam exasperandae. D.48.19.42.2

[2] In paenalibus Causis benignius interpretandum. D.50.17.155.2.3

[3] Nunquam crescit ex post facto praeteriti Delicti Aeftimatio.4

[4] Nonnunquam evenit, ut Aliquorum Maleficiorum Supplicia exacerbantur, quoties nimirum,5 multis Personis grassantibus, exemplo6 Opus sit. Lib.16. p 10 ff de paenis.

Civ. L. Maxims

[1] In an interpretation of law, punishments are better moderated than toughened.1

[2] In penal cases, one should interpret (the law) liberally.2

[3] The estimation of a past crime never increases after the fact.3

[4] It sometimes comes to pass that as the penalties of some crimes are increased, (this) action truly serves as an example for many people lying in wait.4

Maxims & Rules of the LAW1

vid Vol. 4. p. 151.

[1] Lex est tutissima Cassis, sub Clypeo Legis Nemo dicipitur.2 2 Inst. 56. 526.

[2] Justitia debet esse libera, quia nihil iniquis3 venali justitia; plena, quia Justitia non debet claudicare; & celeris, quia Dilatio est quaedam Negatio.4 2 Inst. 56.

[3] Lex uno Ore Omnes Alloquitur. Ibid 184.

[4] Nihil Aliud potest Rex, etc., quam quod de Jure potest. 2 Inst. 187.

[5] Pendente Lite nihil innovetur. Ibid. 208.

[6] Lex dilatores5 semper exhorret. 2 Inst. 240.

[7] Potestas regia est facere Justitiam. ibid. 374.

[8] Nemo6 contra Recordum verificare per Patriam. 2 Inst. 380.

[9] Melior est Conditio Possidentis. Ibid. 391.

[10] Absoluta Sententia Expositore non indiget. Ibid. 533.

[11] Lex beneficialis Rei consimili Remedium praestat. Ibid. 689.

[12] Si Petens deficit in uno cadit in omnibus. Hale’s FNB. 452 Note

[13] Ex nudo Pacto non Oritur Actio. 1. Salk. 129 vid. 1 Salk 24 Harrison’s Case.

Maxims & Rules of the LAW

see Vol. 4. p. 151.

[1] The law is the safest helmet; under the shield of the law no one is deceived.1

[2] Justice should be free, because nothing is as unjust as justice for sale; complete, because justice should not be lacking; and speedy, because delay is a kind of denial.2

[3] The law addresses all with one mouth.3

[4] The king can do nothing other than what he can do by law.4

[5] In a pending lawsuit, nothing is to be altered.5

[6] The law always dreads delays.6

[7] The power of the king is to do justice.7

[8] No one (can) verify against a record by the country (i.e. by a jury).8

[9] The condition of the possessor is better.9

[10] An absolute proposition does not require an explanation.10

[11] A favorable law furnishes a remedy for a similar case.11

[12] If the person seeking (i.e. the petitioner) is lacking in one thing he falls in all.12

[13] An action does not arise from a bare contract (i.e. a contract without consideration).13

The first page (p. 161) of Quincy’s maxim collection in volume three of the Law Reports, P347, Reel 4, QP 57. See Cox Chart, Appendix II, infra. The page, which is entitled “Maxims & Rules of the Law,” is cross-referenced to Quincy’s compilation of Roman law maxims in volume four. As with the Roman law maxims, this collection was written in an even hand and does not present significant evidence of later insertions of additional maxims or citations. My thanks to Elizabeth Papp Kamali.

Maxims etc.

[1] In every Art or Science there are Principia & Postulata, of which it is said, Altiora ne quaesiveris,1 & Principia probant, & non probantur, because every Proof ought to be by a more high & supreme Cause, & nothing can be more high & supreme2 than the Principals themselves, and therefore ought to be approved because they cannot be proved. 3 Rep. 40.a.

[2] Contra Principia negantem3 non est disputandum. 1 Inst.16.a. 232.b. 343.a.

[3] Nulla Curia quae Recordum non habet potest mandare Carceri. 1 Salk 200. Groenvelt vs Burwell

[4] Actio personalis moritur cum Personâ. How This Max: is extended & limited. Vid Nelson’s Lex Test:. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57.4

[5] Stabit Presumptio donec probetur in contrarium. 4 Rep. 71.b.

[6] Exceptio in non exceptis firmat Regulam. 1 Lilly Abr. 559 Exceptio

[7] Oportet Politiam obedire Legibus non Leges Politiae. 4 Bac. Abr. 287. Per Twisden.

Maxims etc.

[1] In every art or science there are principles and postulates, of which it is said, do not seek the higher things, and principles prove, and are not proved, because every proof ought to be by a more high and supreme cause, and nothing can be more high and supreme than the principles themselves, and therefore ought to be approved because they cannot be proved.”1

[2] Contrary to denying (them), principles should not be disputed.2

[3] No court which does not have a record can commit (a person) to prison.3

[4] A personal action dies with the person.4

[5] A presumption will stand until it is proved to the contrary.5

[6] An exception establishes the rule in those things not excepted.6

[7] It is necessary that the polity obeys the laws, not that the laws obey the polity.7

Maxims etc.

[1] Mala est expositio1 quae corrumpit viscera textus. Plowd. Eng: Edit (1761) 288.2

[2] Non omnium quae a majoribus constituta sunt ratio reddi potest.

Maxims etc.

[1] Bad is the explanation that destroys the inner parts of the text.1

[2] A reckoning cannot be rendered for everything that was laid down by (our) ancestors.2

Maxims. etc.1

vid vol. 4. p. 151.

vid. vol. 4. p. 101.2

[1] Omnis Innovatio plus Novitate perturbat quam Utilitate prodest. 1 Bul. 138. 1 Salk 20.

[2] Sic utere3 tuo ut Alienum non laedas. 1 Salk 22.

[3] Qui Rationem in Omnibus quaerunt, Rationem subvertunt. 2 Rep. 75. vid4 p 181 max. 7

[4] Jura Naturalia sunt immutabilia. 7 Rep. 13. Hob 87.5

[5] Lex citius vult tolerare privatum Damnum, quam publicum Malum. 1 Inst. 252.b.6

[6] Quando Lex Aliquid Alicui concedit, concedere videtur7 id sine quo Res ipsa esse non potest. 1 Inst. 56.a. 2 Inst 309.8 4 Inst. 111. 3 Rep. 12. 47. 11 Rep. 52.9

[7] Optimus Interpres Legum Consuetudo.10 2 Inst 18. 228. 282. 4 Inst. 73.11 Custom has sometimes prevailed ag:t a positive Law.12

[8] Malus Usus abolendus est. Lit 212. 1 Inst 141.a. 4 Inst. 274.13

[9] Quae in Consuetudinibus non Diuturnitas Temporis, sed soliditas Rationis est considerandae. Co. Lit: 141.a.14

[10] Consuetudo licet sit magnae Authoritatis, nunquam tamen praejudicat Manifestae Veritati. 2 Inst. 654. 4 Rep 18.

[11] Et Antecedentibus & Consequentibus sit optima Interpretatio. 2 Inst. 317. 2 Rep. 71.

[12] Relatio sit ad proximum Antecedens, nisi impediatur Sententia.15 2 Rep. 71.

[13] Generalis Clausula non porrigitur ad ea quae specialiter sunt comprehensa aut expressa.16 8 Rep. 118.17

Maxims. etc.

see vol. 4. p. 151.

see vol. 4. p. 101.

[1] All innovation disturbs more by (its) novelty than it benefits by (its) utility.1

[2] Use your own in such a manner as not to damage another’s property.2

[3] They who in all matters seek reason subvert reason.3

[4] Natural laws are unchangeable.4

[5] The law should sooner tolerate a private harm than a public evil.5

[6] When the law grants anything to anyone, it is also seen to grant that without which the thing itself cannot be possessed.6

[7] Custom is the best interpreter of laws.7 Custom has sometimes prevailed against a positive law.8

[8] A bad use should be abolished.9

[9] With regard to customs, what should be considered is not the length of time, but the solidity of reason.10

[10] Although custom is of great authority, nevertheless it is never prejudicial to manifest truth.11

[11] The optimal interpretation is (derived) from that which came before and that which followed.12

[12] The preceding is a relation to the next, unless the meaning is impeded.13

[13] A general conclusion is not extended to those things that are specifically comprehended or expressed.14

Edward Coke, First Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (London, 1628), Maxwell, pp. 449‒450. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School. See p. 373, note 9, infra.

Maxims etc.

[1] Ubi Lex est specialis & Ratio ejus generalis, generaliter est accipienda. 2 Inst 43. 83. 10 Rep. 101.1

[2] Apices Juris non sunt Jura.2 4 Rep. 46. 1 Inst 356.a 8 Rep. 56. 1 Inst 283.b3

[3] Qui haeret in Litera etc. 283.b. 365.b. 381.b.4

[4] Nimia subtilitas in Jure reprobantur. 4 Rep. 7.5

[5] Ubi eadem Ratio, idem Jus. 1 Inst 10.a. 191.a.6 2 Inst 619.689 7 Rep. 18.

[6] Et cessante Ratione Legis, cessat Lex. 2 Inst. 11.7

[7] Nemo contra Factum venire potest. 2. Inst. 66.8

[8] Nemo tenetur exponere se Infortuniis & Periculis. 1 Inst 162.a 253.b.9 2 Inst. 483.10

[9] Talis debet esse Metus, qui cadere potest in Virum Constantem non meticulosum.11 Ibid.12

[10] Qui non cadunt in13 Virum constantem Virum, vani Timores sunt. 2 Inst 483.14 7 Rep. 27.15

[11] Qui facit per Alium, facit per se.16 1 Inst. 258.a.17 4 Inst. 109. 10 Rep. 33. vid p.182. Max 4. p.173 Max 8

[12] Omnis Ratihabitio retrotrahitur, & mandato18 aequiparatur.19 1 Inst. 245.a. 258.a. 9 Rep. 106.

[13] Quando plus fit quam fieri debet, videtur etiam ipsum fieri quod faciendum est.20 8 Rep. 85 vid. Vol. 1. p.171.

[14] Modus & Conventio vincunt Legem.21 1 Inst 41b.22 166.a. 2 Rep. 73. 1 Ld. Raymd. 517

Maxims etc.

[1] Where the law is specific and its reasoning is general, it should generally be accepted.1

[2] Points of law are not the laws (themselves).2

[3] He who adheres to the letter (of the law) (adheres to the bark/cork.)3

[4] Too much subtlety in the law is rejected.4

[5] Where (there is) the same reason, (there is) the same right.5

[6] And when the reason for a law ceases, the law (itself) ceases.6

[7] No one can go against (i.e. contradict) a deed.7

[8] No one is obligated to expose himself to misfortune and peril.8

[9] It should be such a fear as could befall a (normally) constant, unfearful man.9

[10] Fears that do not befall a constant man are vain.10

[11] One who acts through another acts by himself.11

[12] Every ratification relates back, and equals a command.12

[13] When more is done than should be done, just that which should have been done is regarded as being done.13

[14] Moderation and agreement prevail over the law.14

Maxims. etc.

[1] Quicunque Jussu Judicis aliquid fecerit, non videtur alio1 Dolo malo fecisse quia parere necesse est.2 10 Rep. 70, 76. Sed vide. 4 Bac: Abr: 450. bot.3

[2] Domus sua Cuiq est tutissimum Refugium.4 5 Rep 92. 11 Rep 82. 3 Inst. 162.

[3] Appellatione Fundi omne Aedificium & omnis Ager continetur.5 4 Rep. 87. 10 Rep. 33.

[4] Cujus est Solum, ejus est usque ad Caelum.6 1 Inst: 4.a. 9 Rep. 54.

[5] Semper expressum facit cessare tacitum.7 Co Lit. 183.b 210.a

[6] Expressio Eorum quae tacite insunt, nihil operatur.8 1 Inst. 191.a. 205.a. 4 Rep 73. 8 Rep 56. 145. 2 Inst. 365.9 5 Rep 56. Vid 2d Ld Raymd. 115410

[7] Quae Dubitationis Causa tollendae inseruntur, communem Legem non laedunt. 1 Inst 205.a.

[8] Quando Aliquid prohibetur fieri ex directo, prohibetur & per obliquum.11 1 Inst. 223.b. 3 Inst 158.

[9] Quod necessario (vel tacite) insunt intelligitur,12 non deest.13 4 Rep. 22.14 7 Rep 40.15

[10] Res inter Alios acta, alteri nocere non debet.16 6 Rep. 1.49.51. 2 Inst. 513.

[11] Qui prior est Tempore, potior est in Jure. 4 Rep. 3017. 1 Inst. 347.b. 2 Inst. 95.

[12] Utile per inutile non vitiatur.18 1 Inst 3.a.

Maxims. etc.

[1] Whoever does something on command of a judge does not appear to have acted with evil intent because it was necessary to comply.1

[2] To each, one’s own house is the safest refuge.2

[3] Every building and every field is contained within the name of the estate.3

[4] Whose is the soil, owns all the way to the heavens.4

[5] That which is expressed always makes that which is unspoken cease.5

[6] The expression of those things that are contained in silence has no effect.6

[7] Those things which are introduced with the motive of removing doubt do not harm the common law.7

[8] When anything is prohibited to be done directly, it is also prohibited indirectly.8

[9] What is understood necessarily (or tacitly) does not fail.9

[10] Deeds performed among others should not cause harm to another, i.e., a third party.10

[11] Whoever is first in time is stronger in the law.11

[12] That which is useful is not spoiled by that which is useless.12

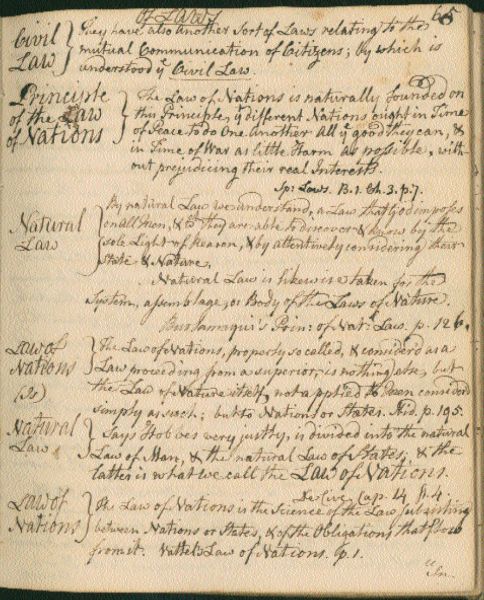

The third page (p. 173) of Quincy’s maxim collection in volume three of the Law Reports, P347, Reel 4, QP 57. See Cox Chart, Appendix II, infra, pp. 432‒33. The page is entitled “Maxims, etc.” and adopts a complicated format, in contrast to the other two maxim compilations. The left-hand margin overflows with multiple source citations, which are tied to the maxim text through an informal footnoting system employing numbers, letters, and symbols alike. Quincy’s hand was uneven, and he frequently struck out text. Although he left marginal space for footnotes, Quincy’s planning was imperfect. Thus he frequently had to squeeze in additional references interlineally. My thanks to Elizabeth Papp Kamali.

Maxims etc.

[1] Quod alias bonum & justum est, si per Vim vel Fraudem petatur, Malum & Injustum efficitur. 3 Rep. 78.

[2] Fucatus Error nuda Veritate in multis est probabilior. 2 Rep. 72.73

[3] Ex verbo generali Aliquid excipitur.1 1 Inst 47.a.

[4] Conditio adimpleri debit priusquam sequatur Effectus.2 1 Inst 201.a.

[5] Conditio beneficialis quae Statum construit3 benigne scundum4 verborum Intentionem est interpretanda. Odiosa autem quae Statum destruit; stricte secundum Verborum Proprietatem est accipienda.5 1 Inst 218.a. 8 Rep. 90.6

[6] Benigne faciendae sunt Interpretationes Chartarum, ut Res magis valeat quam pereat.7 1 Inst 36.a 183.b.8

[7] Verba Intentioni, non econtra, debent inservire. 8 Rep 94.

[8] Verba debent intelligi ut Aliquid operentur.9 8 Rep. 94. Bacon. 18

[9] Verba accipienda sunt cum Effectu.10 4 Rep 51.

Francis Bacon, The Elements of the Common Law (London, 1639); Maxwell, p. 237. See p. 389, note 8, infra, and p. 403, note 8, infra.

Maxims etc.

[1] That which is at other times good and just, if sought through force or fraud, becomes bad and unjust.1

[2] A colored error is in many things more acceptable than naked truth.2

[3] From a general discourse anything is made an exception.3

[4] A condition should be fulfilled before the effect follows.4

[5] A beneficial condition which builds an estate should be interpreted liberally according to the intention of the words; however, an odious one, which destroys an estate, should be understood strictly according to the proper signification of the words.5

[6] Interpretations of writings/deeds should be made liberally so that the thing is worth more rather than that it come to nothing.6

[7] Words should serve intent, not the contrary.7

[8] Words should be understood so that they effect something.8

[9] Words should be understood in connection with (their) effect.9

Maxims etc.

[1] Verba aequivoca & in Dubio posita intelliguntur in digniori & potentiori sensu.1 6 Rep. 20.

[2] Verba Chartarum fortius accipiuntur contra Proferentem.2 1 Inst 36.a. 183.a. 5 Rep 7. 10 Rep 59 Bacon. 11

[3] Verba debent intelligi secundum subjectam materiam.3 1 Inst 36.a. vid. 4 Rep. 12.13 &c.

[4] Quae ad unum finem loquuta sunt, non debent ad Alium detorqueri.4 Ibid.

[5] Affectio tua Nomen imponit Operi tuo. 1 Inst 49.b.

[6] Vigilantibus, non dormientibus, Jura subveniunt.5 2 Rep. 26. 4 Rep. 10. 82. 2 Inst. 690. Coke’s Compl. Cop. Sect. 55.

[7] Communis Error facit Jus.6 Dr. & Stud. Diag 1 Chap. 26. 4 Inst 240

[8] Necessitas vincit Legem. Quod necessarium est licitum.7 5 Rep. 40. 10 Rep 61.

[9] Necessitas est Lex Temporis. 8 Rep 69.

[10] Consensus tollit Errorem.8 5 Rep. 36. 40. 1 Inst 294.a 2 Inst 123

[11] Nemo plus Juris in Alium transferre potest quam Ipse habet.9 1 Inst 309.b10 4 Rep 24. 6 Rep. 57. 68. 8 Rep 63.

Christopher St. German, Doctor and Student (London, 1554), Maxwell, pp. 24‒26. See page 393, note 7, infra.

Maxims etc.

[1] Words that are equivocal and doubtfully set down are [to be] understood in their most fitting and powerful sense.1

[2] The words of deeds are understood more strongly against the grantor.2

[3] Words should be understood according to the subject matter.3

[4] Those things which are spoken to one end should not be directed toward another.4

[5] Your state of mind imposes a name on your work.5

[6] Laws aid the vigilant, not the sleeping.6

[7] A common error makes law.7

[8] Necessity conquers the law to the extent that it is necessary to permit it.8

[9] Necessity is the law of time.9

[10] Consensus removes error.10

[11] No one can transfer to another more of a right than he himself has.11

Sir Edward Coke (1552‒1634). Frontispiece, Edward Coke, Three Law Tracts (London, 1764); Maxwell, p. 575. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School.

Maxims. etc.

[1] Quolibet Concessio fortissime contra Donatorem interpretanda est.1 1 Inst 36.a. 183.a2 5 Rep. 7. 10 Rep 59.

[2] Accessorium non ducit, sed sequitur suum Principale.3 1 Inst. 152.a.

[3] Id certum est, quod Certum reddi potest.4 1 Inst 45.b. 96.a. 142.a

[4] Omne Majus includit Minus, Cui licet quod Majus, non debet quod Minus est non licere.5 4 Rep. 23. 5 Rep. 115. 9 Rep. 49.

[5] Omne Maius trahit ad se Minus.6 6 Rep. 43

[6] Quod licitum est pro Minore, & pro Majore licitum est. 8 Rep. 41.

[7] Mala grammatica non vitiat Chartam7 1 Inst. 146.b. 6 Rep. 39. 9 Rep. 48.

[8] Nemo debet Rem suam sine facto aut Defectu suo amittere.8 1 Inst. 265.a.9 8 Rep. 9210

Maxims. etc.

[1] Every grant should be interpreted most strongly against the donor.1

[2] An accessory does not lead, but follows its own principal.2

[3] That is certain which can be made certain.3

[4] Every greater thing includes the lesser; anybody who is permitted as to the greater should not be barred as to the lesser.4

[5] Every greater thing draws the lesser to itself.5

[6] What is permitted for the lesser is also permitted for the greater.6

[7] Bad grammar does not void a writing/deed.7

[8] No one should lose his property without his own act or failing.8

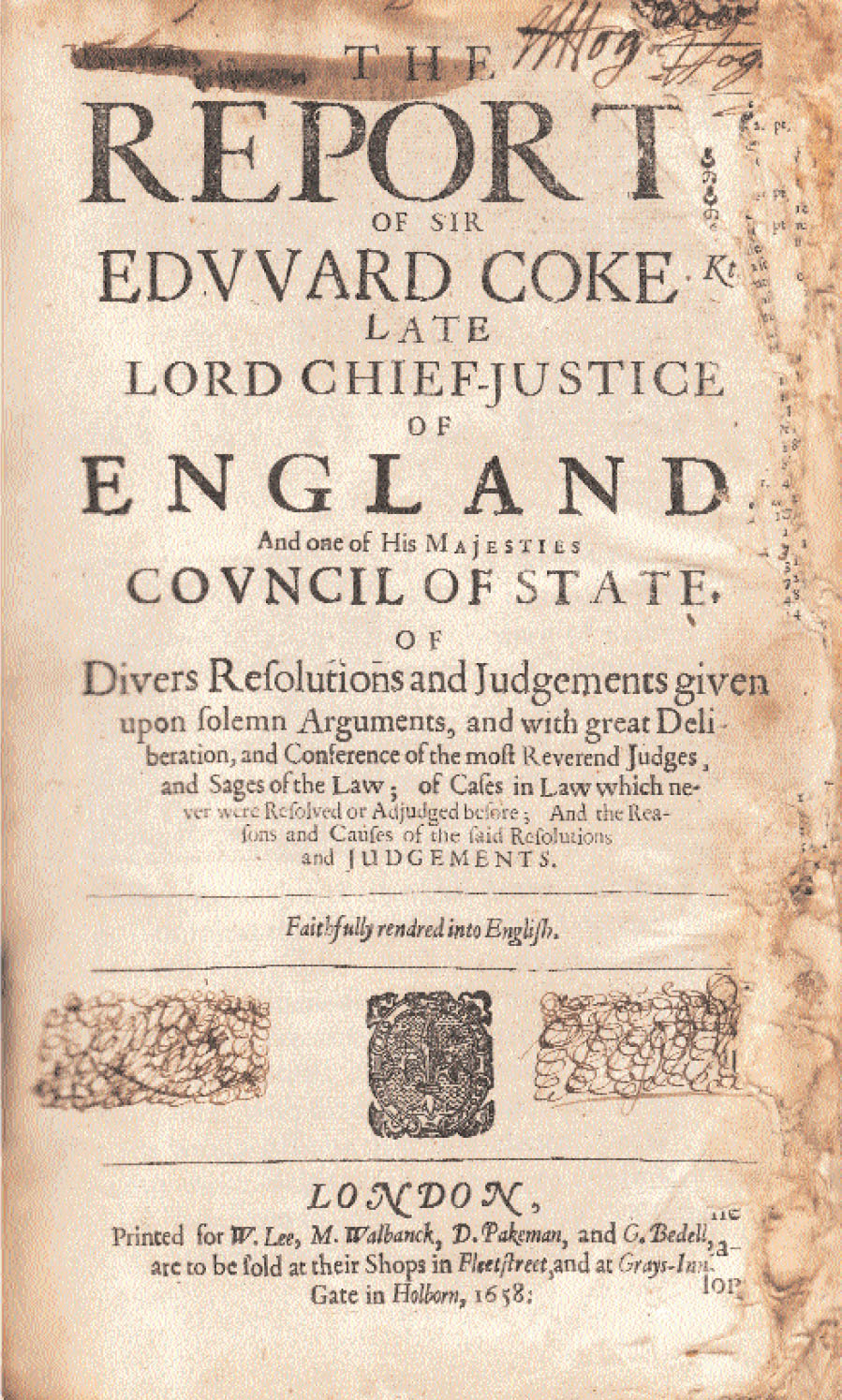

Edward Coke, The Report (London, 1658), Maxwell; pp. 295‒97. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School. This was the first English edition of parts I–XI.

Maxims, etc.

[1] Praestat cautela quam Medela.1 2 Inst 299. 1 Inst. 304.b.

[2] De Minimis non curat Lex.2 1 Inst 54.a. 2 Inst 306

[3] Interest Rei publicae ne quis Re sua male utatur.3 6 Rep. 37.

[4] Dolosus versatur in generalibus4 3 Rep 80

[5] Dona clandestina sunt semper suspiciosa. Ibid.

[6] Clausulae inconsuetae semper inducunt suspicionem5 Ibid

[7] Mandata licita6 strictam Interpretationem recipiunt, sed illicita latam & extensivam7 Bacon 66. 3 Inst 51.

[8] Quando Aliquid Mandatur, mandatur & omne per quod pervenitur ad Illud.8 5 Rep. 115. vid. 2 Inst. 48. 83.9

[9] Crimen non contrahitur nisi nocendi Voluntas intercedit. Bracton Lib.1. ch 4.10

[10] Voluntas non reputabitur pro facto.11 3 Inst 6912 11 Rep. 98.13

[11] Non officit14 Conatus, nisi sequitur15 Effectus. 11 Rep. 98. 6 Rep. 42.

[12] Poenae potius moliendae sunt, quam exasperandae.16 3 Inst 220. Yet Severity of Punishment is to this End, ut Pena17 ad Paucos, Metus ad omnes perveniat; for there is Misercordia etc.18 Co Lit. 294.

Maxims, etc.

[1] Precaution is preferable to a remedy.1

[2] The law does not attend to trivial matters.2

[3] It is of interest to the republic3 that no one uses his property badly.4

[4] A deceitful person is occupied with generalities.5

[5] Clandestine gifts are always suspicious.6

[6] Uncustomary conclusions always introduce suspicion.7

[7] Lawful commands receive a strict interpretation, but unlawful ones a broad and extensive interpretation.8

[8] When anything is ordered, everything by which it is attained is also ordered.9

[9] A crime is not committed unless the intention to injure exists.10

[10] The will is not reckoned according to the act.11

[11] An attempt is not detrimental unless the effect follows.12

[12] Punishments should preferably be softened, rather than exasperated.13 Yet severity of punishment is to this end, so that pain reaches few, fear reaches all, for there is mercy, etc.14

First page of the first printed edition of Henri de Bracton, De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae (London, 1569). See Maxim [9], pp. 400‒401, and note 10, p. 402, supra. Courtesy, Coquillette Rare Book Room, Boston College Law School.

Maxims. etc.

[1] Qui non habet in Aere, luat in Corpore. 2 Inst 173.

[2] Impunitas semper ad Deteriora invitat, & continuum affectum tribuit delinquendi. 4 Rep. 45.1 5 Rep. 109.

[3] Minatur Innocentibus, qui parcit nocentibus 4 Rep. 4.2

[4] Salus Populi3 est suprema Lex.4 10 Rep. 139.

[5] Delinquens per Iram provocatus, puniri debet Mitius5 2 Inst 55.

[6] Quod Quis6 ob Tutelam Corporis sui fecerit, Jure id fecisse videtur.7 1 Inst 162.a. 2 Inst 384. 590. 3 Inst. 56.

[7] Vim vi repellere licet, modo fiat cum moderamine inculpatae tutelae.8 2 Inst. 162.a.9

[8] Clam Delinquens magis punitur quam palam. 8 Rep 127.

[9] Frustra Legis Auxilium invocat, qui in Legem committit. 3 Inst. 64.

[10] Merito Beneficium Legis amittit, qui Legem ipsum subvertere intendit. 2 Inst 53.

[11] Summa Ratio est, quae pro Religione facit. 5 Rep. 14. 10 Rep. 55. 11 Rep. 50.10 1 Inst. 341.a.

[12] Quod fieri non debet, factum valet.11 5 Rep. 38.12

[13] Mitius imperanti melius paretur. 3 Inst. 23.24.163.

Maxims. etc.

[1] He who does not have money, suffers in his body.1

[2] Impunity always incites toward worse (crimes) and imparts a continuous disposition toward wrongdoing.2

[3] He who spares wrongdoers threatens the innocent.3

[4] The welfare of the people is the supreme law.4

[5] A wrongdoer provoked by anger should be punished more lightly.5

[6] That which one does for the protection of his own body is seen to have been done justly.6

[7] It is permitted to repel force with force, on condition that it is done by means of blameless defense.7

[8] A wrongdoer is punished more in secret than publicly.8

[9] He calls upon the assistance of the law in vain who commits injustice against the law.9

[10] He justly loses the benefit of the law who endeavors to subvert the law itself.10

[11] The highest reason is that which acts for religion.11

[12] That which should not be done is valid once done.12

[13] One commanding gently is more easily obeyed.13

Maxims. etc.

[1] Plus peccat Author, quam Actor. 5 Rep. 99. 3 Inst. 167.

[2] Culpa est immiscere se Rei ad se non pertinenti1 1 Inst. 368.b. 2 Inst. 208. 444.2 3 Inst. 91.

[3] Idem est facere, & nolle prohibere, cum posse.3 3 Inst. 158.

[4] Qui non obstat, quod obstare4 potest facere videtur.5 2 Inst. 146.

[5] Quod prius est, verius est. 1 Inst 347.b

[6] Verba accipienda in mitiore6 Sensu.7 4 Rep. 13. 17.8 20. 25. vid 4 Bac: Abr: 505. Cases Time of Holt 39.9

[7] Benignior Sententia in Verbis generalibus, seu dubiis, est praeferenda. 4. Rep. 15.

[8] Sensus verborum ex Causa Dicendi accipiendus est. 4 Rep. 13. 14.

[9] Sermo relatus ad Personam intelligi debet de Conditione Personae. 4 Rep. 16.

[10] Quod non apparet, non est.10 2 Inst. 479.

[11] De non apparentibus, & non Existentibus, Eadem est Ratio. 4 Rep. 47. 2 Inst. 20.11

[12] Multa conceduntur per Obliquum, quae non conceduntur de Directo. 6 Rep. 47.

Sir Edward Coke, Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (London, 1642), Maxwell, p. 546. See p. 413, note 10, infra.

Maxims. etc.

[1] The author sins more than the actor.1

[2] It is wrong to meddle with a matter not pertaining to oneself.2

[3] It is the same to do as to not prohibit what is possible.3

[4] He who does not oppose that which he could oppose is seen to do it.4

[5] That which is first is more true.5

[6] Words should be understood in the most lenient sense.6

[7] The more liberal meaning should be preferred for general, or doubtful, statements.7

[8] The sense of words should be understood from the reason for speaking.8

[9] A remark related to a person should be understood from the circumstances of the person.9

[10] That which is invisible does not exist.10

[11] Regarding the invisible and the nonexistent, the reckoning is the same.11

[12] Many things are conceded indirectly that are not conceded directly.12

Maxims. etc.

[1] Qui semel Actionem renunciavit, amplius repetere non potest.1 8 Rep. 59.

[2] Ambiguum Placitum interpretari debet contra Proferentem. 1 Inst 303.b

[3] Probationes debent esse evidentes, perspicuae & faciles intelligi.2 1 Inst. 283.a.

[4] Ex Diuturnitate3 Omnia praesumuntur solemniter Acta.4 1 Inst. 6.b. 2 Inst. 362.5

[5] Plus valet unus oculatus Testis, quam auriti decem. 4 Inst. 297.6

[6] Omnia praesumuntur legitime facta, donec probetur in Contrarium.7 1 Inst. 232.b.

[7] Injuria non praesumitur. Ibid.

[8] Odiosa & Inhonesta non sunt8 praesumenda. 10 Rep. 56. 1 Inst. 78.b.9

[9] Stabitur Praesumitioni,10 donec probetur in Contrarium.11 1 Inst. 373.b. 2 Rep. 48. 4 Rep. 71.

[10] Res judicata pro veritate habetur.12 1 Inst. 39.a.13 2 Inst. 360.14 573.15 380.16

Maxims. etc.

[1] He who once retracts an action cannot pursue it further.1

[2] One should interpret ambiguous silence against the one offering it.2

[3] Proof should be evident, manifest, and easy to understand.3

[4] After a length of time all things are presumed to have been done solemnly.4

[5] One eyewitness is worth more than ten listeners.5

[6] All things are presumed legitimately done, until it is proved to the contrary.6

[7] Injury is not presumed.7

[8] Hateful and dishonest (acts) are not presumed.8

[9] A presumption will stand until it is proved to the contrary.9

[10] An adjudicated matter is held as the truth.10

Maxims. etc.

[1] Idem est Nihil dicere, & insufficienter dicere. 2 Inst. 453. 178

[2] Cum Confitente Mitius est agendum. 11 Rep. 30. 4 Inst 66.

[3] In Criminalibus Probationes debent esse Luce clariores.1 3 Inst. 26.2 210.

[4] Fatetur Facinus, qui Judicium fugit. 3 Inst. 188. 5 Rep. 109.

[5] Judicandum est Legibus, non Exemplis.3 3 Inst. 212. 4 Rep. 33.

[6] Exempla illustrant non restringunt Legem. Co Lit 24.a

[7] Multa in Jure communi contra Rationem Disputandi4 pro communi Utilitate introducta sunt.5 Co Lit. 70.b.

[8] Ratio potest allegari deficiente Lege—But it must be Ratio vera & legalis6 & non apparens.7 Co Lit. 191.a.

[9] Nulla Impossibilia aut Inhonesta sunt praesumenda, vera autem & honesta, & posibilia Co: Lit. 78.b.

[10] Nihil quod est inconveniens est licitum. Ibid 97.b.

[11] Neminem oportet esse sapientiorem8 Legibus.9 Ibd: 97.b.

[12] Qui adimit medium dirimit Finem. Ibid 161.a

[13] Qui obstruit Aditum, destruit Commodum. Ibid. 161.a

[14] Vim vi repellere licet, modo fiat moderamine10 inculpatae Tutelae11 non ad sumendam vindictam, sed ad propulsandam Injuriam.12 Co: Lit: 162.a.

Maxims. etc.

[1] It is the same to say nothing and to say too little.1

[2] With a confession, it should be pursued more gently.2

[3] In criminal cases, proofs should be clearer than light.3

[4] He who flees judgment confesses a crime.4

[5] One should judge from laws, not from examples.5

[6] Examples elucidate, not restrain, the law.6

[7] Many things contrary to logical argument were received into the common law for the common good.7

[8] Reason can be alleged in a deficient law—but it must be true and legal reason and not (merely) apparent.8

[9] Nothing impossible or dishonest should be presumed, but instead what is true, honest, and possible.9

[10] Nothing that is unsuitable is permitted.10

[11] It is necessary that no one be wiser than the laws.11

[12] He who takes away the means frustrates the end.12

[13] One who obstructs access destroys a convenience.13

[14] It is permitted to repel force with force, on condition that it is done by means of blameless defense, not to take revenge but to fend off injury.14

Maxims. etc.

[1] Quoties in Verbis Nulla est ambiguitas, ibi Nulla Expositio contra Verba expressa fienda est. Haw. Abr. p. 223

[2] Vita Reipublicae Pax est. Co. Lit. 168.a.

[3] Jus accrescendi inter Mercatores pro Beneficio Commercii locum non habet. Ibid. 182.a.

[4] Quando Aliquid prohibetur fieri ex Directo prohibetur & per Obliquum.1 Co: Lit 223.b.

[5] Dormit Aliquando Jus, Moritur Nunquam. Ibid. 279.b.

[6] Dormiunt aliquando Leges, nunquam moriuntur. 2 Inst. 161.

[7] Reipublicae Interest suprema Hominum Testamenta rata haberi. Co Lit 322.b.

[8] Verba relata hoc maxime operantur per Referentiam ut in eis in esse videntur.2 Ibid 359.a.

[9] Frustra fit per plura, quod fieri potest per Pauciora. Ibid 362.b.

[10] Cumunis3 Opinio is of Authority, & stands with ye Rule of Law, A Communi4 Observantia non est recodendum:5 and again, Minime mutanda sunt quae certam habuerunt Interpretationem.6 Co: Lit: 364.b. 365.a.

[11] Culpa est Rei se immiscere ad se non pertinenti. vid. p.179. max. 2. Ibid. 368.b.7

Maxims. etc.

[1] Where there is no ambiguity in the words, then no explanation against the plain words is to be made.1

[2] The life of the republic is peace.2

[3] A right of increase (i.e. right of survivorship) does not have a place among merchants for the benefit of commerce.3

[4] When anything is prohibited to be done directly, it is also prohibited indirectly.4

[5] A right sometimes sleeps; it never dies.5

[6] Laws sometimes lie dormant; they never die.6

[7] It concerns a republic greatly that the final testaments of men be held ratified.7

[8] Words to which reference is made in an instrument have the same effect and operation as if they were inserted in the instrument referring to them.8

[9] It is pointless to do with more that which can be done with fewer.9

[10] The common opinion is of authority, and stands with rule of law. One should not depart from common observance. And again, matters that have had a certain interpretation should be changed as little as possible.10

[11] It is wrong to meddle with a matter not pertaining to oneself.11

Sir Edward Coke, Second Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (London, 1642), p. 315. See Quincy’s concluding maxim, Lex Angliae est Lex Misericorniae, Maxim [8], p. 427, infra, six lines up from bottom.

Maxims. etc.1

[1] The Severity of the Common Law, respecting Felonies was Ut—

Paena ad Paucos, Metus ad Omnes perveniat. For it is truly said. Etsi—

Meliores sunt quos ducit Amor, tamen plures sunt quos corrigit Timor. Co Lit. 392.b.2

[2] Nemo punitur sine Injuria, facto, seu Defalta; and Actus Legis Nemini damnosus. 2 Inst. 287.

[3] Ubi Lex est specialis, & Ratio ejus generalis, generaliter accipienda est 2 Inst. 433 id. p. 172. max.1.

[4] In omni Re nascitur Res quae ipsam Rem exterminat. Ibid. 15.

[5] Ignorantia4 Judicis saepenumero Calamitas Innocentis Ibid. 30. 591.5

[6] Contemporanea Expositio est fortissima in Lege. 2 Inst. 10. 11. 136. 139. 181.6

[7] Omnis Consensus tollit Errorem.7 2 Inst. 123

[8] Lex Angliae est Lex Misericordiae.8 2 Inst. 315

Maxims. etc.

[1] The severity of the common law respecting felonies was that—

Punishment reaches few; fear reaches all. For it is truly said. Though—

Better off are those whom love leads, nevertheless greater in number are those whom fear corrects.1

[2] No one is punished without an injury, deed, or default; and an act of law is damning to no one.2

[3] Where the law is specific and its reasoning is general, it should generally be accepted.3

[4] In every thing, something arises which eradicates the thing itself.4

[5] The ignorance of the judge is oftentimes the misfortune of the innocent.5

[6] A contemporary explanation is strongest in the law.6

[7] The consensus of all removes error.7

[8] The law of England is the law of mercy.8

* A version of this introduction first appeared in volume 39 of the Arizona State Law Journal (Summer, 2007), ii, 317. I am most grateful to the talented student editors of that law review.

1. See Robert Stevens’s classic Law School: Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1983). (Hereafter, “Stevens.”) For both Litchfield and Yale in the 1960s see the fine essays of John H. Langbein and Laura Kalman, respectively, in History of Yale Law School: The Tercentennial Lectures (New Haven, Conn., 2004), pp. 17‒52, 154‒237.

2. See Paul D. Carrington, “The Revolutionary Idea of University Legal Education,” 31 William & Mary L. Rev. 527 (1990). (Hereafter, Carrington, “University Legal Education.”)

3. Wythe, a great law teacher, did most of his teaching outside of a college, taking pupils in his chambers. Wythe taught at William and Mary from only 1780 to 1790, when he resigned “in anger.” See Carrington, “University Legal Education,” supra, p. 537. Jefferson and Monroe were educated by Wythe privately. Interestingly, Wythe refused to sign Patrick Henry’s license, leaving it to the other two examinees to admit him. See Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar (Boston, 1911), p. 165. (Hereafter, “Warren.”)

4. See the standard accounts in Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession in America, Volume 1: The Colonial Experience (Norman, Okla., 1965), pp. 30–33. (“This kind of training or apprenticeship … had many serious defects.” p. 33); Warren, supra, pp. 165–87 (“As a rule, the lawyer was too busy a man to pay much attention to his students …” p. 166). See also Robert Lefcourt’s 1983 Ph.D. thesis, “Democratic Influences on Legal Education from Colonial Times to the Civil War,” University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, which argues that the primary purpose of the apprenticeship method, described as “irrelevant and impractical,” was the “monopolistic tendency” of “ruling lawyers.” Id., pp. 72–79. Even Lawrence M. Friedman emphasized the negative aspects of apprenticeship. “At worst, an apprentice went through a haphazard course of drudgery and copy-work, with a few glances, catch-or-catch can, at the law books.” Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (2d ed., New York, 1985), p. 98. Of course there were some well publicized bad experiences, such as that of William Livingston’s 1745 “invective” against his pupil master, James Alexander of New York. See Warren, pp. 167–69. But, as we will see, there was another side to the story. The best and most balanced account is Charles R. McKirdy’s “The Lawyer As Apprentice: Legal Education in Eighteenth Century Massachusetts,” 28 J. of Legal Education (1976), p. 124. McKirdy astutely observes that “Sir William Blackstone took the opportunity offered in his introductory Vinerian Lecture at Oxford [1758] to blame most of the ills besetting the legal profession on the ‘pernicious’ custom of apprenticeship.” Id., p. 135. See William Blackstone, A Discourse on the Study of Law (Oxford, 1758), p. 28. As the first teacher of English common law within a university setting, Blackstone’s conflict of interest was apparent. And Blackstone inspired other university law teachers to attack the apprenticeship method. Conspicuous among these was Daniel Mayes at the important Transylvania University Law Department in Lexington, Kentucky, who cited Blackstone while attacking apprenticeship in an introductory lecture in 1833. See M. H. Hoeflich, “Plus Ça Change, Plus C’est La Même Chose: The Integration of Theory and Practice in Legal Education,” 66 Temple Law Review, pp. 123, 133–34 (1993). See also Paul D. Carrington’s excellent essay, “Teaching Law and Virtue at Transylvania University: The George Wythe Tradition in the Antebellum Years,” 41 Mercer Law Review 673 (1989–1990), pp. 691–96, 697–99. As Hoeflich observes, “One of the ‘hot’ topics in legal education has been the debate over the extent to which it is desirable and possible to integrate a more practical approach into the predominantly theoretical classroom model of legal education used in most American law schools.” Id., p. 123. Indeed, nothing changes.

5. Warren actually tried to make the argument that apprenticeship was such a bad system that it made good lawyers because they had so much to overcome, an argument I would like to try on my law students! “When all is said, however, as to the meagerness of a lawyer’s education, one fact must be strongly emphasized—that this very meagerness was a source of strength. Multum in parvo was particularly applicable to the training for the Bar of that era.” Warren, supra, p. 187. Of course, what else could be expected from the great historian of the Harvard Law School! See Charles Warren, History of the Harvard Law School and of Early Legal Conditions in America (New York, 1908), 3 vols.

6. See E. Alfred Jones, American Members of the Inns of Court (London, 1924), pp. ix–xxx. Between 1674 to 1776 over sixty Virginians attended the Inns of Court, “but only twenty engaged in practice once they got home,” and of these “some never practiced.” W. Hamilton Bryson, Legal Education in Virginia 1779–1979 (Charlottesville, 1982), p. 9. Formal educational programs had deteriorated in the Inns of Court by this time. “The essence of membership in an English Inn was that it was a prestigious place to do a legal apprenticeship,” usually by “an apprenticeship to a practicing lawyer in London with residence in the Inn.” Id., p. 9. “In fact, many Virginians who were members of an Inn had no intention of ever practicing law but joined for purely social purposes.” Id., p. 9. On the “marked decay” in the “‘system’ of legal education” in the Inns of Court, see David Lemmings, Gentlemen and Barristers: The Inns of Court and The English Bar 1686–1730 (Oxford, 1980), pp. 75–109.

7. See Diary and Autobiography of John Adams (L. H. Butterfield ed., Cambridge, Mass., 1964), vol. 1, pp. 136–37, vol. 2, p. 274. (Hereafter, “Adams, Diary.”) See also Daniel R. Coquillette, “Justinian in Braintree: John Adams, Civilian Learning, and Legal Elitism, 1758–1775” in Law in Colonial Massachusetts 1630–1800 (eds. D. R. Coquillette, R. J. Brink, C. S. Menand, Boston, 1984), pp. 395–400. (Hereafter, “Coquillette, Adams.”) For the highly comparable history of medical apprenticeship or pupilage and the “professionalization of Boston medicine during the last half of the eighteenth century,” see Philip Cash, “The Professionalization of Boston Medicine, 1760–1803” in Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts (eds. P. Cash, E. H. Christianson, J. W. Estes, Boston, 1980), pp. 69–100. The “Harvard Medical Institution,” the area’s first medical school, was not founded until 1782. Id., p. 89.

8. One of these exceptions is John Adams’s law “Commonplace Book.” See Legal Papers of John Adams (eds. L. Kinvin Wroth, Hiller B. Zobel, Cambridge, Mass., 1976), vol. 1, pp. 4–25. This dates from ca. 1759 and is a very rudimentary affair compared to Quincy’s Law Commonplace. See discussion at Section I, “The Manuscript,” infra. Another exception is Thomas Jefferson’s Legal Commonplace Book, which was edited by Gilbert Chinard in 1926. See The Commonplace Book of Thomas Jefferson: A Repertory of his Ideas on Government (G. Chinard ed., Baltimore, 1926) and the discussion in Douglas L. Wilson, “Thomas Jefferson’s Early Notebooks,” 42 William and Mary Quarterly (1985), pp. 433–52. Jefferson also had an Equity Commonplace Book which is in the Huntington Library. See the discussion in Douglas L. Wilson’s fine edition of Jefferson’s Literary Commonplace Book (D. L. Wilson ed., Princeton, N.J., 1989), p. 195, n. 195 and in his article cited above. Wilson sets the date for the beginning of Jefferson’s Legal Commonplace Book as “the period 1765–1766” which makes it almost exactly a contemporary of Quincy’s book. Id., p. 198, n. 14.

See also the remarkable commonplace collection, spanning the 17th century to 1935, found in the Bounds Law Library at the University of Alabama School of Law and described in Paul M. Pruitt Jr., David I. Durham, Commonplace Book of Law: A Selection of Related Notebooks from the Seventeenth Century to the Mid-Twentieth Century (Tuscaloosa, Ala., 2005). Another important exception was the exhibit at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale, organized by Earle Havens in 2001. See Earle Havens, Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century (New Haven, Conn., 2001). My own distinguished colleague, Karen Beck, organized an equally important exhibit of law student notebooks at the Boston College Law School Rare Books Room in 1999. See Karen Beck, Notable Notes: A Collection of Law Student Notebooks, Boston, 1999; Karen Beck, “One Step at a Time: The Research Value of Student Notebooks,” 91 Law Library, p. 29 (1999). The latter article emphasizes the importance of the law commonplace of Theophilius Parsons Sr. (1750–1813), created in 1773. Id., p. 32. See Theophilius Parsons Jr., Memoir of Theophilius Parsons (Boston, 1859), p. 137.

9. See Arthur E. Sutherland, The Law at Harvard (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), pp. 79–92. (Hereafter, “Sutherland.”)

10. See Daniel R. Coquillette, “‘Mourning Venice and Genoa’: Joseph Story, Legal Education, and the Lex Mercatoria” in FromLex Mercatoria to Commerical Law (ed. Vito Piergiovanni, Berlin, 2005), pp. 14–26. (Hereafter, “Coquillette, Joseph Story.”) See also Sutherland, supra, pp. 92–139; R. Kent Newmyer, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story: Statesman of the Old Republic (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1985), pp. 237–70. (Hereafter, “Newmyer.”)

11. See Coquillette, Joseph Story, supra, pp. 14–26; Newmyer, supra, pp. 269–71. Newmyer observes that “much of Story’s grand plan for a cadre of conservative lawyer-statesmen went unrealized.” Id., p. 269. This may be a fair statement in the short run, but the future of Harvard Law School surely provided such a “cadre”!

12. See Sutherland, supra, pp. 140–61.

13. See the American Law Review (October, 1870), “Summary of Events,” set out at Sutherland, supra, p. 140. See also Warren, supra, pp. 342–78.

14. Christopher Columbus Langdell, Cases on Contracts (Cambridge, Mass., 1871). The most insightful commentator on Langdell today is my esteemed colleague, Bruce Kimball. See, for example, Bruce A. Kimball, “‘Warn Students That I Entertain Heretical Opinions, Which They Are Not to Take as Law’: The Inception of Case Method Teaching in the Classrooms of the Early C. C. Langdell, 1870–1885,” 17 Law and History Review 56 (1999), pp. 91–93, 124–25; Bruce A. Kimball, Pedro Reyes, “The ‘First Modern Civil Procedure Course’ as Taught by C. C. Langdell, 1870–78,” 47 American Journal of Legal History (2005), pp. 257–58, 289–95.

15. See Section II, “Pedagogy,” supra.

16. See discussion in Daniel R. Coquillette, “‘The Purer Fountains’: Bacon and Legal Education,” in Francis Bacon and the Refiguring of Early Modern Thought: Essays to Commemorate the Advancement of Learning (1605‒2005) (J. R. Solomon, C. G. Martin, eds., London, 2005), pp. 145–72.

17. See Section II, “Pedagogy,” infra.

18. See Section I, “The Manuscript,” infra.

19. John Adams appreciated this fact, and not only trained himself in Roman law, but used it systematically in his Vice-Admiralty practice. See Coquillette, Adams, supra, pp. 382–95.

20. See M. H. Hoeflich, pp. 123–27. William R. Trail, William D. Underwood, “The Decline of Professional Legal Training and a Proposal for its Revitalization in Professional Law Schools,” 48 Baylor L. Rev. 201 (1996), pp. 201–08, 210–11, 244–45.

21. See Reports, pp. 318–40, and annotations.

22. See the discussion at note 34, infra. See also The Law Commonplace, p. [21], n. 10, infra.

23. I am particularly grateful to my research assistant, Kevin Willoughby Cox, Harvard Law School Class of 2006, for his invaluable and careful work on the manuscripts. See Appendix I I, infra, the “Cox Chart.”

24. See p. 347, Reel 4, QP56, “Vol. 1 1763,” pp. 122–41.

25. Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 47.

26. Id., vol. 1, p. 47.

27. John Locke, Works (London, 1823), vol. 3, pp. 331 ff.

28. Id., p. 336.

29. Hale’s advice was one of the first readings assigned by Jeremy Gridley to his new apprentice, John Adams. “Then he took his [Gridley’s] Common Place Book and [illegible] gave me Ld. Hales Advice to a Student of the Common law.” Adams, Diary, October 25, 1758, vol. 1, p. 55. The prestige and influence of Hale’s Preface was doubtless bolstered by the posthumous publication of his Analysis of the Law, an immensely influential and important book. It was originally written around 1670 and not published until 1713 as The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England; by a Learned Hand (London, 1713). For the importance of this “pathbreaking work,” this “comprehensive method of analysis,” see Harold J. Berman, Charles J. Reid Jr., “The Transformation of English Legal Science: From Hale to Blackstone,” 45 Emory Law Journal 437 (1996), pp. 486–89.

30. Rolle’s Abridgment (London, 1668), “Publisher’s Preface,” n.p. [8].

31. Id.

32. Id., n.p. [8].

33. Legal Papers of John Adams (L. Kinvin Wroth, Hiller B. Zobel, eds., Cambridge, Mass., 1965), vol. 1, pp. 4–25.

34. I am most indebted to Kevin W. Cox for deciphering the “Red Reports” cross citations. According to Samuel M. Quincy the manuscripts of the Reports “consist of three volumes: one with paper covers (from the original color of which it is referred to as “Red Reports”) and two others bound in parchment, and numbered “3” and “4.” The first two volumes of this set are missing, and were probably destroyed in a fire by which the reporter’s law library was lost.” Reports, “Preface,” pp. iii–iv. But Samuel M. Quincy is at least partly wrong, as the volume containing the Law Commonplace is identical in binding and paper page size (20.0 cm. by 16.1. cm.) to “Vol. 3” and “Vol. 4” containing the Reports, and is marked “Vol. 1.” There are also citations from the Reports to “Vol. 1” which clearly connect to the Law Commonplace substantively. So, at most, only one volume is missing. But there is a fourth volume, also of identical paper and page size (20.0 cm. by 16.1 cm.), which has a new cover. This is P 347 Reel 4 QP54. It is much thinner than the other three, and was dismissed by Samuel M. Quincy as “the fragment of another volume apparently just commenced.” It contained the “Middlesex Cases” (1771–1772) detailed at Reports, pp. 318–40, which were not in Quincy’s hand. Could it be the missing “Vol. 2”? Or a fragment of the volume? Most likely, Samuel M. Quincy was correct in dismissing the thin volume, but the identical paper and page size causes one to pause. Otherwise, “Vol. 2” was lost. It could have perished in the fire. A happier thought is that it may be discovered someday. What a fascinating find that would be.

35. See F. H. Lawson, The Oxford Law School 1850–1965 (Oxford, 1968), pp. 4–5 (hereafter, “Lawson”); Sutherland, supra, pp. 19–25. Lawson was certainly right in observing that “Blackstone exerted a greater influence in the North American colonies and subsequently in the United States than in England …” Lawson, p. 4. But both the theoretical style and the politics of his Commentaries earned Blackstone powerful enemies, such as Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, writing to Madison in 1826, observed that when “the honied Mansfieldism of Blackstone became the student’s hornbook, from that moment, that profession (the nursery of our Congress), began to slide into toryism …” Thomas Jefferson, Works (P. L. Ford, ed., New York, 1905), vol. 12, pp. 455–56. See Sutherland, p. 13. Blackstone still has his pedagogical enemies. See Duncan Kennedy, “The Structure of Blackstone’s Commentaries,” 28 Buffalo Law Review 205 (1979). In addition, a good deal of the practiced legal training in England was outside both the Inns of Court and the universities, and remained more practical than formal. See David Lemmings, Professors of the Law, Barristers and English Legal Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2000), pp. 107–48.

36. Francis Stoughton Sullivan, A Plan For the Study of the Feudal and English Laws in the University of Dublin (Dublin, 1761), p. 4.

37. At least one thousand sets were exported to America before 1771, when a pirated edition was published in Philadelphia by Robert Bell. One thousand and four hundred copies were subscribed in advance, with one New York dealer taking two hundred and thirty-nine. See Sutherland, p. 25. Although Blackstone’s Commentaries were not available to Quincy when he began the Law Commonplace, he owned a set at his death in 1775. See Quincy’s Reports, Appendix 9, “Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Estate of Josiah Quincy Jun: Esq: Deceas’d,” Item 67. At least one volume of this set survived, for a time, in the library of Phillips Andover. It is now gone. Again, many thanks to Mark Sullivan, superb reference librarian. In addition, there is one citation to the first volume (1765) of Blackstone’s Commentaries at Law Commonplace, p. 94 [82], which may be a later addition, although apparently in Quincy’s hand. See page 281, n. 2, infra. There are several citations to Blackstone’s earlier Analysis of the Laws of England (Oxford, 1756). See Law Commonplace, pp. n.p. [6], n.p. [10] and 89 [77]. See also n. 46, infra.

38. See Carrington, supra, pp. 527‒38 and note 3 supra.

39. See John H. Langbein, “Blackstone, Litchfield, and Yale: The Founding of the Yale Law School,” History of the Yale Law School (ed. Anthony T. Kronman, New Haven, Conn., 2004), pp. 17–36. (Hereafter, “Langbein, The Founding.”)

40. Id., p. 30.

41. Id., p. 30.

42. Oxenbridge Thacher (1719–1765) was one of Boston’s most “eminent lawyers of the period.” See the biography set out in Appendix 6 to the Reports, vol. 5, infra. He was Quincy’s law tutor from 1763 to Thacher’s death in July, 1765. See Josiah Quincy, Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy, Jr. (2d ed., Boston, 1874), pp. 6–7. (Hereafter, “Memoir.”) See also Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduate, vol. xv: Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College in the Classes 1761–1763 (Boston, 1970), p. 479. On Thacher’s death in 1765, Quincy “took over the office and as much of the practice as he could handle.” Id., p. 479. According to John Adams, Thacher believed strongly in commonplacing. “He [Thacher] says He is sorry that he neglected to keep a Common Place Book when he began to study Law, and he is half a mind to begin now.” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 55 (October 25, 1758).

43. See, for example, the citation at Law Commonplace, p. 105 [transcript 90] to “Red Rep. 70 Angier v. Jackson.” That is a citation to Quincy’s “red” notebook, P347 Reel 4 QP55 (now rebound in brown), which contained the manuscript of his report of Angier v. Jackson, Reports, p. 84. As Samuel M. Quincy observed in his “Preface” to the Reports, this volume had “paper covers, (from the original color of which it is referred to as ‘Red Reports,’).” See Reports, p. iii. Quincy also cross-referenced the important case of Baker v. Mattocks at Law Commonplace, p. 106 [transcript 91]. Baker v. Mattocks was in the “Red Reports” at page 57, and in the Reports at page 69. I am most grateful to Kevin Cox, my brilliant research assistant, for deciphering these cross-references!

44. Hale’s Preface, n.p. [page 8].

45. Law Commonplace, Quincy n.p., Transcription p. [7].

46. Id., n.p., Transcription p. [9]. Quincy followed Reeve’s advice and relied on Wood’s Institute of the Laws of England for his preliminary “heads + divisions.” As J. L. Barton observed of Wood’s Institute, “Its success was certainly due in part to the fact that it was the only book of its kind in print until Blackstone’s Commentaries was published, but it is only fair to say that the tenth edition appeared as late as 1 7 7 2, when the Commentaries had been in circulation for some years.” J. L. Barton, “Legal Studies” in The History of the University of Oxford (ed. T. H. Ashton), vol. 5, The Eighteenth Century (eds. L. S. Sutherland, L. C. Mitchell, Oxford, 1986), p. 600.

The first volume of Blackstone’s Commentaries did not appear until 1765, and there is only one mention of it in Quincy’s Law Commonplace, which may be a later addition. See note 37 supra. There are several citations to Blackstone’s more rudimentary Analysis of the Laws of England [with] Introductory discourse on the Study of the Law (Oxford, 1756) and just preceding Reeve’s Directions to his Nephew, at Law Commonplace, Quincy n.p., Transcription, p. [6], but Quincy made little use of it, apparently preferring Wood’s “divisions” and Hale’s system. See further citations to Blackstone’s Analysis at p. n.p. [10] and p. 89 [77] of the Law Commonplace. John Adams was also aware of Blackstone’s Analysis, observing: “This day I am beginning my Ld. Hales History of the Common Law, a Book borrowed of Mr. Otis, and read once already, Analysis and all, with great Satisfaction. I wish I had Mr. Blackstone’s Analysis that I might compare, and see what Improvements he has made upon Hale’s.” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 169.

47. Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, pp. 54–55 (October 5, 1758). See also p. 32, infra, and accompanying note.

48. Id., p. 55. See also pp. 31–33, infra.

49. See Warren, pp. 175–76.

50. Langdell’s pioneering casebook on contracts contains not one word of explanatory text. To Langdell, the essence of study was to “select, classify and arrange all cases which had contributed to the growth, development, or establishment of any of its [contracts] essential doctrines.” C. C. Langdell, A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts (Boston, 1871), p. vii. In a sense, Langdell assisted with one aspect of commonplacing, the arrangement and sequence of cases, but continued to leave the student with the task of analysis and application. As Langdell noted: “Law, considered as a science, consists of certain principles or doctrines. To have such a mastery of these as to be able to apply them with constant facility and certainty to the ever-tangled skein of human affairs, is what constitutes a true lawyer; and hence to acquire that mastery should be the business of every earnest student of law.” Id., p. vi.

51. See Sutherland, pp. 92–139; Warren, History of Harvard Law School (New York, 1908), vol. 1, pp. 413–506.

52. See Coquillette, Joseph Story, supra, pp. 24–26. See also note 10, supra.

53. The Miscellaneous Writings of Joseph Story (ed. W. W. Story, Boston, 1852), pp. 380–81.

54. Newmyer, p. 40.

55. Id., p. 40.

56. Id., p. 40.

57. Id., pp. 41–42. For an account of the sparse early American law reporting, see Erwin C. Surrency, “Law Reports in the United States,” 25 Am. J. Legal Hist. 58 (1981); Alan V. Briceland, “Ephraim Kirby: Pioneer of American Law Reporting,” 16 Am. J. Legal Hist. (1972). There is an excellent book about early Supreme Court reports, Morris L. Cohen & Sharon Hamby O’Connor, A Guide to the Early Reports of the United States (1995). See also W. Hamilton Bryson, “Virginia Manuscript Law Reports,” 82 Law Libr. Jour. 305–11 (1990) and my case for Josiah Quincy’s claim as the first true American law reporter, Daniel R. Coquillette, “First Flower—The Earliest American Law Reports and the Extraordinary Josiah Quincy, Jr. (1744–1775),” 30 Suffolk Univ. L. Rev. 1 (1976), pp. 1–15 (hereafter, “Coquillette, Law Reports”).

58. Newmyer, p. 41.

59. Newmyer, p. 42.

60. Newmyer, p. 41.

61. Id., p. 44.

62. See Id., p. 41; Coquillette, Adams, pp. 360–76. As M. H. Hoeflich has observed: “During the period from the Revolution to the Civil War…. American lawyers were far less parochial than they were in the succeeding century. Many had a lively interest in Roman law and its descendent, the modern civil law. At the same time, this interest rarely became expertise.” M. H. Hoeflich, “An Aborted Attempt to Translate Justinian’s Digest in Antebellum America,” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtgeschichte, 122 Band, p. 198 (Vienna, 2005).

63. Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, pp. 54–55 (October 25, 1758). Francis Dickins was the 16th Regius Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge, serving from 1714 to 1755, nearly 41 years!

64. Id., vol. 1, pp. 173–74. See also vol. 1, p. 199. By “Vinnius,” Adams was referring to Arnoldus Vinnius (1586–1657), whose popular commentary on Justinian’s Institute, In Quattuor libros institutionum imperialium commentarius academicus was to be found in many eighteenth-century editions, such as the Venice edition of 1736. These were usually edited by Johann Gottlieb Heineccius (1681–1741). Johannes Van Muyden, a civilian scholar, lived from 1652 to 1729. His Compendiosa institutionum Justiniana tractatie was eventually acquired by Adams from Gridley’s library and remains today in the Boston Public Library. See Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, p. 57, n. 2. See also p. 27, supra, and accompanying notes.

65. These extraordinary similarities were first noticed by my talented research assistant, Kevin Cox, Harvard Law School 2006. Dickins’s program was not too strenuous! According to the letter copied into Quincy’s notebook, “If a general knowledge only of the Civil Law is desired in the most short and compendious Method, the most advisable way is to read Wood’s Institutes [Thomas Wood, A New Institute of the Imperial or Civil Law (London, 1704), with subsequent editions in 1712, 1721, and 1730] in its natural order, translated into English by W. Strahan: [Jean Domat, Civil Law in its Natural Order (trans. William Strahan, London, 1722), with subsequent printings in 1737 and 1772]. [T]hese two authors will furnish a careful reader with the main principals [sic] of the Civil Law in all its several branches.” “Vol. 4” P347, Reel 4, QP58, p. 148. Only if “the intent be to become as compleat a master as may be of the Civil Law” was it “necessary to begin with the first Element and to read Justinian’s Institutions …” Id., p. 148. In short, no need for a gentleman to actually read law from the original sources to have “a general knowledge of the civil law”! This rather cavalier approach was reflected in other “quick and easy” civil law guides of the period, some of which were cross-cited to Blackstone’s Commentaries. See, for example, the short book by one of Dickins’s successors as Regius Professor, Samuel Hallifax, who served from 1770 to 1782. Hallifax’s An Analysis of the Roman Civil Law (Cambridge, 1774) was extensively cross-referenced to Blackstone, and was certainly not “heavy lifting,” even by the standards of modern student “outlines”! Certainly no Latin was required. Quincy’s laborious collection of Latin maxims was not a Roman Law course, but it involved much more effort and familiarity with original Latin sources than the “courses” of civil law Dickins and Hallifax prepared for the “gentleman scholar” of Cambridge in the eighteenth century!

66. “There was a continuing tradition in England of small books purporting to assist law students by isolating the ‘principal grounds and maxims’ of the law. This tradition went back to Abraham Fraunce’s (1557?–1633) The Lawyiers Logick (1588), a book designed to introduce Fraunce’s fellows at Gray’s Inn, which included Bacon, to the Ramis dialectic. Indeed, the tradition could be said to include St. Germain’s Doctor and Student, as early as 1523, where the ‘Student of the Common Law’ invoked ‘dyvers pryncyples that be called by those learned in the lawe maxymes … for every one of those maxymes is suffycyent auctorytie to hym selfe to such an extent that it is fruitless to argue with those who deny them.’ The maxims in St. Germain’s book were apparently the basis of the first English collection of maxims, Principia sive Maxima Legum Anglie (London, 1546) located and described in a most scholarly study by John C. Hogan and Mortimer D. Schwartz. There followed books like William Fulbeck’s (1560–1603) A Direction or Preparative to the Study of the Lawe (1600) (Fulbeck being another Gray’s Inn lawyer), Sir Henry Finch’s (1558–1625) Nomotechnia (1613), and William Noy’s (1577–1634) A Treatise of the Principall Grounds and Maximes of the Lawes of this Kingdome (1641). The latter was a treatise written originally in Law French and published in English long after the author’s death. It remains difficult to show when any of these little treatises was first written and circulated at the Inns of Court. It is therefore hard to prove the exact sequence of ideas between them, and from them to Bacon.” Daniel R. Coquillette, Francis Bacon (Stanford, 1992), p. 37 (hereafter, “Coquillette, Bacon”).

67. Id., pp. 37–38.

68. Id., p. 39.

69. Id., p. 39.

70. Id., p. 40.

71. Reports, p. 209.

72. Reports, p. 201.

73. Coquillette, Bacon, p. 39, citing Bacon’s Maximes (1631), Works of Francis Bacon (ed. J. Spedding, R. L. Ellis, D. D. Heath, London, 1857–74), vol. VII, p. 321. (Hereafter, “Works of Francis Bacon.”)

74. As to “the comparison of legal systems to discover universal rules when they existed” and its importance to Joseph Story and other American lawyers of the early Republic, see M. H. Hoeflich, “Comparative Law in Antebellum America,” 4 Washington University Global Studies Review 535, 537–44 (2005). Bacon compared maxims to a ‘magnetic needle’ that “points at the law, but does not settle it.” Works of Francis Bacon, vol. XIII, p. 67. “The magnetic needle was useful because it accurately reflected the natural phenomenon of the earth’s polarity. Likewise, useful jurisprudence began with the empirical facts of the law that existed in the courts and the statute books, and then moved, step by step, to generalities that were genuinely useful, because they were a product of induction from reality. But it was also already plain that Bacon’s maxims were intended to do more than simply describe and restate existing law. By accurately identifying the rational, consistent and systematic ‘middle axioms’ of the system, the development of the law could be directed toward more harmony and more reason.” Coquillette, Bacon, p. 46.

75. “Mr. Otis reasoned with great learning and zeal …” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 267 (Dec. 20, 1768).

76. Reports, p. 203.

77. C. C. Langdell, A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts (Boston, 1871), p. vi.

78. Matthew Hale talked of a seven-year period, or longer, for the commonplacing process. “Touching the Method of the study of the Common Law, I must in general say thus much to the Student thereof; It is necessary for him to observe a Method in his Reading and Study; for let him assure himself, though his memory never be so good, he shall never be able to carry on a distinct serviceable Memory of all, or the greatest part he reads, the end of seven years, nor a much shorter time, without the helps of Use or Method; yea what he hath Read seven years since, will, without the help of Method, or reiterated use, be as new to him as if he had scarce ever read it: A Method therefore is necessary, but various, according to every Man’s particular Fancy …” Matthew Hale, “Preface Directed to the Young Students of the Common Law,” in Henry Rolle, Un Abridgment Des Plusieurs Cases … del Common Ley … (London, 1668), n.p.

79. See Coquillette, Law Reports, pp. 1–15.

80. See Mary Sarah Bilder, The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (Cambridge, Mass., 2004), pp. 1–11. (Hereafter, “Bilder.”)