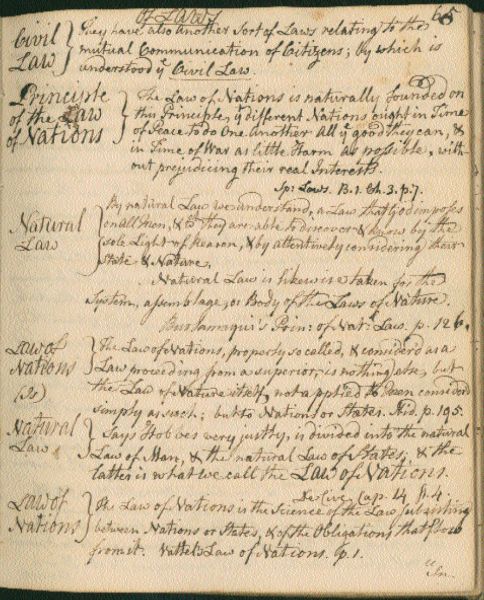

The first page (p. 151) of Quincy’s maxim collection in volume four of the Law Reports, P347, Reel 4, QP 58. See Cox Chart, Appendix II, infra. The page is entitled “Maxims of the Civil Law” and offers a careful, neatly compiled list of Roman law maxims in a fairly even hand. Following the title, Quincy cross-references another collection of maxims in volume three of his Law Reports, as well as another section within volume four discussing ecclesiastical and civil law. The first maxim is the focus of a footnote at the bottom, set off from the main text by a line scored across the page. The note, an excerpt from Wood’s Civil Law, continues on the following page. My thanks to Elizabeth Papp Kamali. Reproduced courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society.

QUINCY’S LATIN LEGAL MAXIMS

Translator’s Note and Introduction

Elizabeth Papp Kamali*

Ch. Just. Have you no Authorities, Gentlemen?

Mr. Gridley. There is no Authority that the Sun shines.

Mr. Auchmuty. But there is Evidence.1

By the early twentieth century, a scholar could assert, without controversy, that the “principal service performed by the average maxim is … to bolster or support a legal viewpoint rather than to decide a case.”2 In Quincy’s time, however, reception of English law was an ongoing process, domestic precedents were not systematically recorded, and American lawyers were taking tentative steps toward defining the weight of various authorities in the colonial courtroom. The exchange quoted above, excerpted from a case recorded by Quincy in his Law Reports, was followed shortly by quotation of a maxim, although the ensuing conversation touched upon a variety of authorities.3 A maxim could carry considerable weight when, for example, the English common law provided a contradictory or unsatisfactory answer. Representing principles that transcend time and space, maxims offered the colonial American lawyer a fresh outlook on perplexing legal questions and a broad framework within which to weigh the merits of either side of an action. Regretfully, Quincy’s early death, which brought his legal career to an abrupt close, precludes a study of his maxim collection in action. Undoubtedly, with his meticulously cross-referenced arsenal of maxims, Josiah Quincy Jr. would have been a dynamo in the courtroom.

Josiah Quincy Jr.’s collection of Latin legal maxims comprises twenty-two pages within two volumes of his Law Reports.4 In volume four, six pages of maxims, entitled “Maxims of the Civil Law” (referred to here as Maxim I), are followed by four blank pages and twenty-four pages of miscellaneous notes on evidence and other legal topics.5 The first of two sets of maxims in volume three is entitled “Maxims & Rules of the Law” (Maxim II).6 Oddly, seven blank pages precede the next set of maxim pages (Maxim III), entitled “Maxims, etc.” Quincy evidently conceived of these as three distinct maxim collections. In both volumes, Quincy’s placement of the maxims toward the end of the book suggests that they may have been viewed as an appendix to the law reports; alternatively, the blank pages available after the Law Reports may have simply been a convenient locale for situating the maxims. Regardless, Quincy’s use of distinct titles for the three separate groupings of maxim pages, while possibly inconsequential, is likely indicative of some schematic vision, perhaps divisible into Roman law (Maxim I), broad principles of law (Maxim II), and maxims dealing with particular substantive legal topics (Maxim III).7 Unfortunately, Quincy’s heavy reliance on Edward Coke in compiling both Maxim II and Maxim III stymie any conclusive effort to differentiate between these two sets of maxims.

All three groupings of maxim pages are written in the same hand, with a large underscored title at the top of each page. Structurally, however, the three sets of maxims differ somewhat. For example, neat organization characterizes the Roman law section in Maxim I, with indentations for each maxim and a separate footnote section at the bottom of some pages.8 Maxim III evokes chaos by contrast, with maxims penned in script ranging from miniscule to large, most likely due to the addition of maxims at later points.9 Furthermore, Quincy employs marginal footnotes to add extensive citation references in Maxim III, sometimes combining alphabetical footnotes with symbols when incorporating a combination of internal and external references or, perhaps, when adding further citations at a later time, thereby disrupting the original alphabetical scheme.10 On one page, Quincy started with the letter b for his first footnote and proceeded next to d, apparently leaving out letters a and c in the anticipation of adding more footnotes later on.11 Quincy’s listing of citations was a work in progress, a reference to which he added further sources over time. He also added maxims at later points, as demonstrated by the fact that some maxims are sandwiched in, penned in a smaller hand, between two other maxims.12 Unfortunately, it is impossible to determine whether the three sets of maxims were compiled simultaneously or at different times, which might explain some of these differences in format.

A few clues hint at Quincy’s method in assembling the maxims and footnotes. Quincy’s references are almost entirely impeccable. When I have run into difficulty tracking down a source, the problem has almost always revolved around my failure to access a particular edition or to recognize at first that Quincy was not citing to an explicit quotation of a maxim, but instead to a more generalized discussion of a related topic. On one occasion where Quincy did provide an erroneous page number, however, I discovered that Coke’s index of maxims (located toward the end of his volume of Reports) provided the same incorrect page number. In this instance, Quincy may have copied the page number, and perhaps the maxim itself, from Coke’s maxim index, rather than accessing the maxim within the body of Coke’s text.13 At the same time, it is possible that Quincy employed a secondary source of maxims and citations, such as a fellow law scholar’s commonplace book, and that this source, in turn, repeated the erroneous page number from Coke’s list. Similarly, one of Quincy’s Roman law maxims has a closer analogue in Coke’s Institutes than in the Digest citation provided by Quincy, suggesting that Quincy was not referencing a copy of Justinian directly but was instead getting his maxims from another source.14 Thus, Quincy may not have been simply paging through Coke’s Institutes, Justinian’s Digest, and other cited texts in search of maxim material, but may have relied instead, at least in part, on other sources.

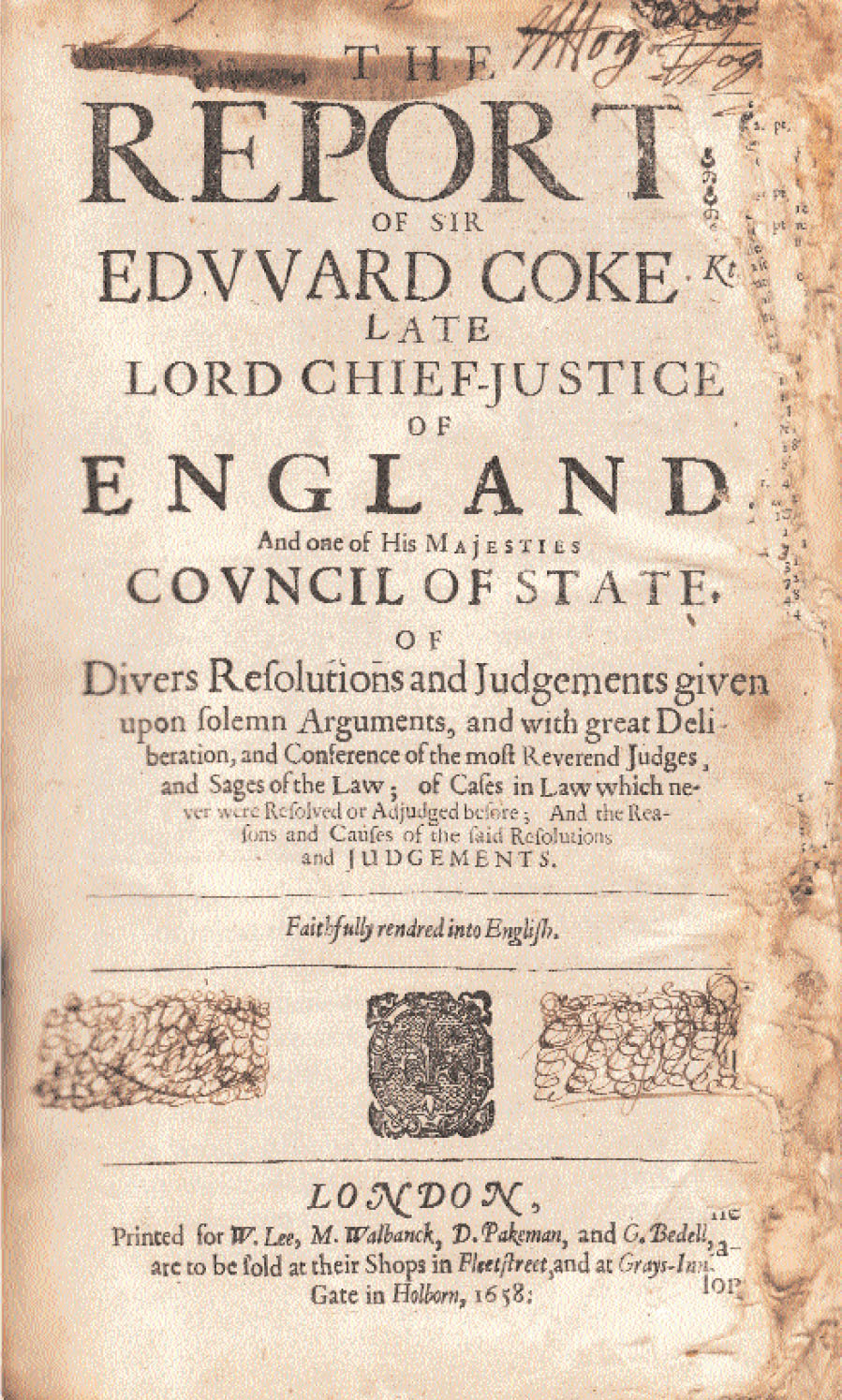

Quincy’s maxims are largely a study of Coke, and his reliance on Coke may have extended to questions of format as well. Some editions of Coke’s Reports display a similarly heavy use of marginal citation notes, employing essentially the same format as that used by Quincy.15 What was the purpose behind these extensive references to Coke and various reporters? Quincy’s careful work in compiling his commonplace book and multiple volumes of law reports seems to rule out an idiosyncratic obsession with compiling lists of citations. The sheer number of marginal citations suggests also that these maxim lists were not merely a memory aid or study guide, in which case a single citation, or perhaps none at all, would have sufficed. Rather, Quincy likely intended to employ these maxim lists actively in devising legal arguments. Perhaps a maxim with several citations carried greater legal weight in his estimation than one which appeared only once in Coke’s Reports. Or perhaps the citations were a means to accessing more extensive supporting material to illuminate the possible application of a particular maxim.16

Several examples illustrate Quincy’s plan for using the maxims. Quincy glossed one maxim with a footnote indicating that exceptions to the maxim’s rule were possible in cases where otherwise “an inconvenience should follow.”17 In another instance, Quincy qualified a maxim describing custom as the best interpreter of laws with the comment that custom may sometimes prevail against a statute.18 He traced this maxim to two sources: one regarding a slander action, and the other discussing the interpretation of charters. Perhaps Quincy viewed the maxims as general propositions of law that could be applied to a variety of causes of action, and his references were an aid to help him track down relevant material to cite in court. In another instance, Quincy referenced a source stating a proposition contrary to that communicated by the maxim itself.19 After recording the familiar maxim that a personal action dies with the person, Quincy cited to Nelson’s Lex Testamentaria with a note-to-self indicating that the referenced text describes how the maxim is “extended & limited.”20 This sophisticated gloss suggests that Quincy likely intended his maxims to serve as a reference to be used in practice, perhaps both for constructing legal arguments and for anticipating potential contrary arguments. This was not a rudimentary index of maxims, but a complex study of legal principles and their limitations.

While Quincy did separate his maxims into three distinct groupings,21 he did not use the same precision in categorizing them as he did, for example, in dividing his commonplace book into distinct topical headings. Broadly speaking, Maxim I cited propositions from Roman law sources. Maxim II dealt in matters pertaining to lawsuits and the administration of justice. This section may have been compiled by Quincy with an eye toward use in the courtroom, where persuasive rhetoric might have employed general statements about law and justice. Maxim III, by contrast, dealt more with the nuts and bolts of what we would today categorize as property law, contracts, testaments, and evidence. Clearly this overlaps with the concept of Maxim II, but the goal here may have been to dig deeper into specific questions of law, rather than speaking of law in its more abstract and general sense.

My translation of Josiah Quincy Jr.’s collection of Latin legal maxims involved close work with the manuscript22 but was aided tremendously by the earlier work undertaken by two other research assistants: Michael H. Hayden, who prepared an initial transcription, and Susannah B. Tobin, who commenced a translation of the maxims and took time out of her busy clerkship schedule to acquaint me with the project. In addition to Tobin’s work, I relied on the Perseus on-line Latin reference,23 my dog-eared copy of Lewis & Short,24 and the various sources cited by Quincy, which often helped clarify the meaning of an otherwise ambiguous maxim.25 When a maxim could lend itself to a more literal or classical translation, as opposed to a “legalistic” paraphrasing, I have erred in favor of the former. In some instances, I have footnoted alternative translations from Latin for Lawyers26 or some other maxim reference book. My final task was to decipher the multitude of textual citations provided by Quincy and to track down his sources27 with the hope of determining why Quincy ever undertook this maxim collection in the first place. I hope the ensuing pages of translated maxims will provide some conclusions.

I should add a note on using the facing pages of Latin and English translation to follow. Generally, footnotes on the left-hand Latin page highlight oddities in the manuscript or, in some cases, alternative phrasings of the maxims as provided in Quincy’s referenced sources. The footnotes on the right-hand page, on the other hand, primarily set out Quincy’s citations in full detail, rendering “3 Rep. 40.a.”, for instance, into “Sir Edward Coke, Reports, part 3 (ist French edition, 1602; ist English edition, 1658), 40.a (Ratcliff’s Case).” As in the above example, references have been fleshed out, wherever practicable, to include chapter headings or other identifying section titles. Where a citation is provided with no additional parenthetical explanation beyond a section title, as above, the reader may assume that the maxim quoted by Quincy was quoted directly in the source. However, where parentheticals are provided and do not expressly indicate that the maxim was quoted, the reader should assume that the maxim was not directly quoted in the source. In many cases, particularly in his marginal footnotes, Quincy referenced texts not for their direct quotation of a maxim but for their discussion of a related legal topic.

In compiling his maxim collection, Josiah Quincy Jr. recognized what Chancellor Kent would declare nearly a century later: “There are scarcely any maxims in the English law but what were derived from the Romans.”28 Perhaps this explains why, on the pages immediately following the curriculum recommended by Professor Francis Dickins at Cambridge, Quincy commenced a collection of excerpts almost exclusively derived from Justinian’s Digest. Aside from footnoting related discourses from Wood’s Civil Law to gloss three of the maxims, Quincy presented his “Maxims of the Civil Law,” as he titled the collection, with only a single citation per maxim. It would appear that these maxims, as suggested by Lord Coke, were propositions “to be of all men confessed and granted without proofe, argument, or discourse.”29 Quincy may have viewed these Roman law maxims as propositions which could stand on their own and, to quote Bacon, which could be “delivered to more several purposes and applications” accordingly.30 Yet Quincy did not entirely adopt Bacon’s approach toward maxims; whereas Bacon favored the delivery “of knowledge in distinct and disjoined aphorisms,” so as to “leave the wit of man more free to turn and toss,”31 Quincy appears to have grouped his civil law maxims into distinct legal categories, to which the modern reader might apply the titles interpretation of law,32 the use of precedent,33 wills and testaments,34 contracts,35 and criminal law.36 This suggests that Quincy pinned the Roman law maxims to a specific substantive context beyond which they should not be too broadly construed.

In another volume of Law Reports,37 Quincy compiled a separate list of maxims entitled “Maxims & Rules of the Law,” comprising a mere three pages.38 This collection has a loose thematic scheme that revolves largely around the general topic of law, lawsuits, and justice.39 For this selection of maxims, Quincy relied heavily on Coke’s Institutes, while also drawing aphorisms from a range of other sources, including Fitzherbert’s Natura Brevium, Salkeld’s and Coke’s Reports, Plowden’s Commentaries, and the Abridgements of both Lilly and Bacon. In contrast to the Roman law maxims, which could sometimes be compartmentalized into substantive categories as specific as contracts or criminal law, these maxims tend to offer broader legal principles. It may be for this reason that Quincy chose the title “Maxims & Rules,” perhaps viewing the two terms as distinct. In this regard, Quincy’s thinking would be aligned with that of John Dodderidge, who distinguished between ‘primary principles’, or maxims, and ‘secondary principles’, or rules.40 From Dodderidge’s perspective, rules are ‘not so well known by the light of nature … and are peculiarly known for the most part, to such only as profess the study and the speculation of the law.’41 By contrast, Coke had little patience for distinguishing among maxims, principles, rules, postulates, or axioms, observing that “it were too much curiosity to make nice distinctions between them.”42 While it is possible to read too much into Quincy’s choice of heading, I believe that he took a view of maxims and rules more akin to Dodderidge than Coke in this respect; this might help to explain Quincy’s decision to compile three separate collections of maxims.

Coke also opined that “it is well said in our books … nest my a disputer l ancient principles del ley.”43 Quincy was not so deferential. In his third collection of maxims, a collection entitled “Maxims, etc.” and separated from “Maxims & Rules” by seven blank pages, Quincy engages the maxims, tests their limits, expands upon their applications, proffers examples, and cites to multiple sources. Lord Esher would observe over a century later that maxims “are almost invariably misleading: they are for the most part so large and general in their language that they always include something which really is not intended to be included in them.”44 Quincy’s view was not so extreme, but he did recognize limits upon the appropriate application of certain maxims. For example, he notes that “Verba accipienda sunt cum Effectu” is a maxim that “holds good in Statutes.”45 Perhaps the maxim, in his view, should not be applied as readily to interpreting contracts or testaments. Similarly, Quincy cites to Coke’s Institutes for guidance as to how the maxim, “Quolibet Concessio fortissime contra Donatorem interpretanda est” should be understood.46 In another instance, he quotes the maxim “Res inter Alios acta, alteri nocere non debet” but cites to “an exception to this Max.” in Coke’s Institutes.47 In glossing the maxims in this manner, Quincy followed Bacon’s example. In his Maximes, Bacon listed the rule, described it and the policy behind it, offered examples, and then turned to limitations or exceptions.48 While not tackling each maxim as systematically as Bacon, or limiting his maxims to a more manageable number, Quincy nevertheless had a similar respect for the depth of information a single maxim could contain. At the same time, Quincy recognized that maxims could be applied erroneously, thereby exposing an uncautious lawyer’s argument to attack.

This third maxim collection is almost entirely attributable to Coke, both the Institutes and the Reports, with a few rare exceptions such as Bulstrode and Salkeld’s Reports, Hawkins’s Abridgment, and Saint German’s Doctor & Student. In fact, of a total of 147 maxims in this collection, a mere six have a primary citation other than to Coke.49 The maxims are loosely arranged by topic, ranging from property law and interpretation of charters,50 to criminal law51 and evidence.52 I believe that this collection of maxims was designed for active use in Quincy’s legal practice, and that the multiple citations were a means for the young lawyer to bolster his maxim-based arguments with specific examples and nuanced interpretations.

postscript

How grateful I am to Professor Daniel R. Coquillette for introducing me to the world of Josiah Quincy Jr., a name only vaguely familiar to me previously in connection with his son, former President of Harvard College. As a budding historian, I take careful note of Prof. Coquillette’s academic style, and I have been impressed by the sensitivity, lighthearted wit, and profound respect with which he has approached the subject of this series. In Prof. Coquillette’s office at Harvard Law School, a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of Josiah Quincy Jr. holds a conspicuous place of honor on the wall, an ever-present reminder of the brilliant young man whose legacy Prof. Coquillette has done so much to promote. I am deeply grateful to Prof. Coquillette for including me in the task of illuminating this portrait of a patriot, and for offering generous guidance, patient mentorship, and an admirable example.

THEMES AND SOURCES IN QUINCY’S MAXIMS

| Page | Total # of Maxims | Main Themes1 | Main Sources (# maxims); fn = footnote; only first listed source recorded | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAXIMS I (“Maxims of the Civil Law”) | ||||

|

151 |

8 |

Interpretation of Law (8) |

Justinian’s Digest (7) Justinian’s Code (1) Wood’s Civil Law (fn) |

Roman law sources. Clear theme throughout. |

|

152 |

6 |

Interpretation of Law (6) |

Justinian’s Digest (6) Wood’s Civil Law (fn) |

Roman law source. Clear theme throughout. |

|

153 |

6 |

Precedent (4) Interpretation of Law/Judgment (2) |

Justinian’s Digest (6) Wood’s Civil Law (fn) |

Roman law source. |

|

154 |

10 |

Wills & Testaments (5) Contracts (5) |

Justinian’s Digest (9) Justinian’s Code (1) |

Roman law sources. |

|

155 |

10 |

Contracts (6) Criminal Law (3) Interpretation of Law/Judgment (1) |

Justinian’s Digest (9) Justinian’s Code (1) Wood’s Civil Law (fn) |

Roman law sources. |

|

156 |

4 |

Criminal Law (4) |

Justinian’s Digest (4) |

Roman law source. Lower half of page blank. |

| MAXIMS II (“Maxims &Rules of the Law”) | ||||

|

161 |

13 |

Law, Lawsuits, and Justice (12) Property (1) |

Coke, Institutes (11) Fitzherbert, Natura Brevium (1) Salkeld’s Reports (1) |

|

|

162 |

7 |

Law, Lawsuits, and Justice (7) |

Coke, Reports (2) Coke, Institutes (1) Salkeld’s Reports (1) Nelson (1) Lilly’s Abridgment (1) Bacon’s Abridgment (1) |

Theme appears to be lawsuits in general, with some reference to principles of law. Greater variety of sources. |

|

163 |

2 |

Interpretation of Law (1) Precedent (1) |

Plowden, Commentaries (1) Justinian’s Digest (1) |

Most of page left blank. |

| MAXIMS III (“Maxims, etc.”) | ||||

|

171 |

13 |

Property (4) Interpretation of Law (3) Custom (3) Precedent (2) Natural Law (1) |

Coke, Institutes (7) Coke, Reports (4) Bulstrode (1) Salkeld (1) |

Quincy packs in maxims on this page and seems to add some later, writing them interlineally. Also introduces elaborate footnoting system to record additional citations. |

|

172 |

14 |

Interpretation of Law (6) Property/Misc. (8)2 |

Coke, Institutes (11) Coke, Reports (3) |

More difficult to discern a theme. Elaborate marginal footnotes. |

|

174 |

12 |

Property/Interpretation of Charters (11) Actions of Court Officers (1) |

Coke, Institutes (8) Coke, Reports (4) |

Difficult to find a theme at first glance, but the references to Coke are primarily to matters regarding property law. Quincy has packed in the maxims, added some later, and filled the margins with footnoted citations. |

|

174 |

9 |

Property/Interpretation of Charters (9) |

Coke, Reports (5) Coke, Institutes (4) |

Marginal footnotes. |

|

175 |

10 |

Property/Interpretation of Charters (10) |

Coke, Institutes (5) Coke, Reports (4) Saint German, Doctor & Student (1) |

Marginal footnotes. |

|

176 |

8 |

Property/Interpretation of Charters (8) |

Coke, Institutes (5) Coke, Reports (3) |

Marginal footnotes. |

|

177 |

13 |

Criminal Law/Deceit (10) Property (3) |

Coke, Institutes (5) Coke, Reports (6) Bacon, Abridgment (1) Bracton (1) |

A fairly clear theme. Marginal footnotes. |

|

178 |

13 |

Criminal Law (11) Misc (2) |

Coke, Institutes (7) Coke, Reports (6) |

A clear theme! Marginal footnotes. |

|

12 |

Interpretation of Statements & Actions/Slander (12) |

Coke, Reports (7) Coke, Institutes (5) |

Marginal footnotes. |

|

|

180 |

10 |

Proof & Evidence (8) Law, Lawsuits, & Justice (2) |

Coke, Institutes (8) Coke, Reports (2) |

Clear theme. Marginal footnotes. |

|

181 |

14 |

Interpretation of Law (7) Criminal Law (5) Property Law (2) |

Coke, Institutes (13) Coke, Reports (1) |

Marginal footnotes. |

|

182 |

11 |

Wills & Testaments (2) Interpretation of Statements & Actions/Slander (1) Property/Misc (8) |

Coke, Institutes (10) Hawkins, Abridgment (1) |

Very difficult to discern a theme. Marginal footnotes. |

|

183 |

8 |

Criminal Law (4) Law, Lawsuits, & Justice (4) |

Coke, Institutes (8) |

Marginal footnotes. |

* A version of this introduction first appeared in volume 39 of the Arizona State Law Journal (Summer, 2007), ii, 317. I am most grateful to the talented student editors of that law review.

1. See Robert Stevens’s classic Law School: Legal Education in America from the 1850s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1983). (Hereafter, “Stevens.”) For both Litchfield and Yale in the 1960s see the fine essays of John H. Langbein and Laura Kalman, respectively, in History of Yale Law School: The Tercentennial Lectures (New Haven, Conn., 2004), pp. 17‒52, 154‒237.

2. See Paul D. Carrington, “The Revolutionary Idea of University Legal Education,” 31 William & Mary L. Rev. 527 (1990). (Hereafter, Carrington, “University Legal Education.”)

3. Wythe, a great law teacher, did most of his teaching outside of a college, taking pupils in his chambers. Wythe taught at William and Mary from only 1780 to 1790, when he resigned “in anger.” See Carrington, “University Legal Education,” supra, p. 537. Jefferson and Monroe were educated by Wythe privately. Interestingly, Wythe refused to sign Patrick Henry’s license, leaving it to the other two examinees to admit him. See Charles Warren, A History of the American Bar (Boston, 1911), p. 165. (Hereafter, “Warren.”)

4. See the standard accounts in Anton-Hermann Chroust, The Rise of the Legal Profession in America, Volume 1: The Colonial Experience (Norman, Okla., 1965), pp. 30–33. (“This kind of training or apprenticeship … had many serious defects.” p. 33); Warren, supra, pp. 165–87 (“As a rule, the lawyer was too busy a man to pay much attention to his students …” p. 166). See also Robert Lefcourt’s 1983 Ph.D. thesis, “Democratic Influences on Legal Education from Colonial Times to the Civil War,” University Microfilms International, Ann Arbor, which argues that the primary purpose of the apprenticeship method, described as “irrelevant and impractical,” was the “monopolistic tendency” of “ruling lawyers.” Id., pp. 72–79. Even Lawrence M. Friedman emphasized the negative aspects of apprenticeship. “At worst, an apprentice went through a haphazard course of drudgery and copy-work, with a few glances, catch-or-catch can, at the law books.” Lawrence M. Friedman, A History of American Law (2d ed., New York, 1985), p. 98. Of course there were some well publicized bad experiences, such as that of William Livingston’s 1745 “invective” against his pupil master, James Alexander of New York. See Warren, pp. 167–69. But, as we will see, there was another side to the story. The best and most balanced account is Charles R. McKirdy’s “The Lawyer As Apprentice: Legal Education in Eighteenth Century Massachusetts,” 28 J. of Legal Education (1976), p. 124. McKirdy astutely observes that “Sir William Blackstone took the opportunity offered in his introductory Vinerian Lecture at Oxford [1758] to blame most of the ills besetting the legal profession on the ‘pernicious’ custom of apprenticeship.” Id., p. 135. See William Blackstone, A Discourse on the Study of Law (Oxford, 1758), p. 28. As the first teacher of English common law within a university setting, Blackstone’s conflict of interest was apparent. And Blackstone inspired other university law teachers to attack the apprenticeship method. Conspicuous among these was Daniel Mayes at the important Transylvania University Law Department in Lexington, Kentucky, who cited Blackstone while attacking apprenticeship in an introductory lecture in 1833. See M. H. Hoeflich, “Plus Ça Change, Plus C’est La Même Chose: The Integration of Theory and Practice in Legal Education,” 66 Temple Law Review, pp. 123, 133–34 (1993). See also Paul D. Carrington’s excellent essay, “Teaching Law and Virtue at Transylvania University: The George Wythe Tradition in the Antebellum Years,” 41 Mercer Law Review 673 (1989–1990), pp. 691–96, 697–99. As Hoeflich observes, “One of the ‘hot’ topics in legal education has been the debate over the extent to which it is desirable and possible to integrate a more practical approach into the predominantly theoretical classroom model of legal education used in most American law schools.” Id., p. 123. Indeed, nothing changes.

5. Warren actually tried to make the argument that apprenticeship was such a bad system that it made good lawyers because they had so much to overcome, an argument I would like to try on my law students! “When all is said, however, as to the meagerness of a lawyer’s education, one fact must be strongly emphasized—that this very meagerness was a source of strength. Multum in parvo was particularly applicable to the training for the Bar of that era.” Warren, supra, p. 187. Of course, what else could be expected from the great historian of the Harvard Law School! See Charles Warren, History of the Harvard Law School and of Early Legal Conditions in America (New York, 1908), 3 vols.

6. See E. Alfred Jones, American Members of the Inns of Court (London, 1924), pp. ix–xxx. Between 1674 to 1776 over sixty Virginians attended the Inns of Court, “but only twenty engaged in practice once they got home,” and of these “some never practiced.” W. Hamilton Bryson, Legal Education in Virginia 1779–1979 (Charlottesville, 1982), p. 9. Formal educational programs had deteriorated in the Inns of Court by this time. “The essence of membership in an English Inn was that it was a prestigious place to do a legal apprenticeship,” usually by “an apprenticeship to a practicing lawyer in London with residence in the Inn.” Id., p. 9. “In fact, many Virginians who were members of an Inn had no intention of ever practicing law but joined for purely social purposes.” Id., p. 9. On the “marked decay” in the “‘system’ of legal education” in the Inns of Court, see David Lemmings, Gentlemen and Barristers: The Inns of Court and The English Bar 1686–1730 (Oxford, 1980), pp. 75–109.

7. See Diary and Autobiography of John Adams (L. H. Butterfield ed., Cambridge, Mass., 1964), vol. 1, pp. 136–37, vol. 2, p. 274. (Hereafter, “Adams, Diary.”) See also Daniel R. Coquillette, “Justinian in Braintree: John Adams, Civilian Learning, and Legal Elitism, 1758–1775” in Law in Colonial Massachusetts 1630–1800 (eds. D. R. Coquillette, R. J. Brink, C. S. Menand, Boston, 1984), pp. 395–400. (Hereafter, “Coquillette, Adams.”) For the highly comparable history of medical apprenticeship or pupilage and the “professionalization of Boston medicine during the last half of the eighteenth century,” see Philip Cash, “The Professionalization of Boston Medicine, 1760–1803” in Medicine in Colonial Massachusetts (eds. P. Cash, E. H. Christianson, J. W. Estes, Boston, 1980), pp. 69–100. The “Harvard Medical Institution,” the area’s first medical school, was not founded until 1782. Id., p. 89.

8. One of these exceptions is John Adams’s law “Commonplace Book.” See Legal Papers of John Adams (eds. L. Kinvin Wroth, Hiller B. Zobel, Cambridge, Mass., 1976), vol. 1, pp. 4–25. This dates from ca. 1759 and is a very rudimentary affair compared to Quincy’s Law Commonplace. See discussion at Section I, “The Manuscript,” infra. Another exception is Thomas Jefferson’s Legal Commonplace Book, which was edited by Gilbert Chinard in 1926. See The Commonplace Book of Thomas Jefferson: A Repertory of his Ideas on Government (G. Chinard ed., Baltimore, 1926) and the discussion in Douglas L. Wilson, “Thomas Jefferson’s Early Notebooks,” 42 William and Mary Quarterly (1985), pp. 433–52. Jefferson also had an Equity Commonplace Book which is in the Huntington Library. See the discussion in Douglas L. Wilson’s fine edition of Jefferson’s Literary Commonplace Book (D. L. Wilson ed., Princeton, N.J., 1989), p. 195, n. 195 and in his article cited above. Wilson sets the date for the beginning of Jefferson’s Legal Commonplace Book as “the period 1765–1766” which makes it almost exactly a contemporary of Quincy’s book. Id., p. 198, n. 14.

See also the remarkable commonplace collection, spanning the 17th century to 1935, found in the Bounds Law Library at the University of Alabama School of Law and described in Paul M. Pruitt Jr., David I. Durham, Commonplace Book of Law: A Selection of Related Notebooks from the Seventeenth Century to the Mid-Twentieth Century (Tuscaloosa, Ala., 2005). Another important exception was the exhibit at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale, organized by Earle Havens in 2001. See Earle Havens, Commonplace Books: A History of Manuscripts and Printed Books from Antiquity to the Twentieth Century (New Haven, Conn., 2001). My own distinguished colleague, Karen Beck, organized an equally important exhibit of law student notebooks at the Boston College Law School Rare Books Room in 1999. See Karen Beck, Notable Notes: A Collection of Law Student Notebooks, Boston, 1999; Karen Beck, “One Step at a Time: The Research Value of Student Notebooks,” 91 Law Library, p. 29 (1999). The latter article emphasizes the importance of the law commonplace of Theophilius Parsons Sr. (1750–1813), created in 1773. Id., p. 32. See Theophilius Parsons Jr., Memoir of Theophilius Parsons (Boston, 1859), p. 137.

9. See Arthur E. Sutherland, The Law at Harvard (Cambridge, Mass., 1967), pp. 79–92. (Hereafter, “Sutherland.”)

10. See Daniel R. Coquillette, “‘Mourning Venice and Genoa’: Joseph Story, Legal Education, and the Lex Mercatoria” in FromLex Mercatoria to Commerical Law (ed. Vito Piergiovanni, Berlin, 2005), pp. 14–26. (Hereafter, “Coquillette, Joseph Story.”) See also Sutherland, supra, pp. 92–139; R. Kent Newmyer, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story: Statesman of the Old Republic (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1985), pp. 237–70. (Hereafter, “Newmyer.”)

11. See Coquillette, Joseph Story, supra, pp. 14–26; Newmyer, supra, pp. 269–71. Newmyer observes that “much of Story’s grand plan for a cadre of conservative lawyer-statesmen went unrealized.” Id., p. 269. This may be a fair statement in the short run, but the future of Harvard Law School surely provided such a “cadre”!

12. See Sutherland, supra, pp. 140–61.

13. See the American Law Review (October, 1870), “Summary of Events,” set out at Sutherland, supra, p. 140. See also Warren, supra, pp. 342–78.

14. Christopher Columbus Langdell, Cases on Contracts (Cambridge, Mass., 1871). The most insightful commentator on Langdell today is my esteemed colleague, Bruce Kimball. See, for example, Bruce A. Kimball, “‘Warn Students That I Entertain Heretical Opinions, Which They Are Not to Take as Law’: The Inception of Case Method Teaching in the Classrooms of the Early C. C. Langdell, 1870–1885,” 17 Law and History Review 56 (1999), pp. 91–93, 124–25; Bruce A. Kimball, Pedro Reyes, “The ‘First Modern Civil Procedure Course’ as Taught by C. C. Langdell, 1870–78,” 47 American Journal of Legal History (2005), pp. 257–58, 289–95.

15. See Section II, “Pedagogy,” supra.

16. See discussion in Daniel R. Coquillette, “‘The Purer Fountains’: Bacon and Legal Education,” in Francis Bacon and the Refiguring of Early Modern Thought: Essays to Commemorate the Advancement of Learning (1605‒2005) (J. R. Solomon, C. G. Martin, eds., London, 2005), pp. 145–72.

17. See Section II, “Pedagogy,” infra.

18. See Section I, “The Manuscript,” infra.

19. John Adams appreciated this fact, and not only trained himself in Roman law, but used it systematically in his Vice-Admiralty practice. See Coquillette, Adams, supra, pp. 382–95.

20. See M. H. Hoeflich, pp. 123–27. William R. Trail, William D. Underwood, “The Decline of Professional Legal Training and a Proposal for its Revitalization in Professional Law Schools,” 48 Baylor L. Rev. 201 (1996), pp. 201–08, 210–11, 244–45.

21. See Reports, pp. 318–40, and annotations.

22. See the discussion at note 34, infra. See also The Law Commonplace, p. [21], n. 10, infra.

23. I am particularly grateful to my research assistant, Kevin Willoughby Cox, Harvard Law School Class of 2006, for his invaluable and careful work on the manuscripts. See Appendix I I, infra, the “Cox Chart.”

24. See p. 347, Reel 4, QP56, “Vol. 1 1763,” pp. 122–41.

25. Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 47.

26. Id., vol. 1, p. 47.

27. John Locke, Works (London, 1823), vol. 3, pp. 331 ff.

28. Id., p. 336.

29. Hale’s advice was one of the first readings assigned by Jeremy Gridley to his new apprentice, John Adams. “Then he took his [Gridley’s] Common Place Book and [illegible] gave me Ld. Hales Advice to a Student of the Common law.” Adams, Diary, October 25, 1758, vol. 1, p. 55. The prestige and influence of Hale’s Preface was doubtless bolstered by the posthumous publication of his Analysis of the Law, an immensely influential and important book. It was originally written around 1670 and not published until 1713 as The History and Analysis of the Common Law of England; by a Learned Hand (London, 1713). For the importance of this “pathbreaking work,” this “comprehensive method of analysis,” see Harold J. Berman, Charles J. Reid Jr., “The Transformation of English Legal Science: From Hale to Blackstone,” 45 Emory Law Journal 437 (1996), pp. 486–89.

30. Rolle’s Abridgment (London, 1668), “Publisher’s Preface,” n.p. [8].

31. Id.

32. Id., n.p. [8].

33. Legal Papers of John Adams (L. Kinvin Wroth, Hiller B. Zobel, eds., Cambridge, Mass., 1965), vol. 1, pp. 4–25.

34. I am most indebted to Kevin W. Cox for deciphering the “Red Reports” cross citations. According to Samuel M. Quincy the manuscripts of the Reports “consist of three volumes: one with paper covers (from the original color of which it is referred to as “Red Reports”) and two others bound in parchment, and numbered “3” and “4.” The first two volumes of this set are missing, and were probably destroyed in a fire by which the reporter’s law library was lost.” Reports, “Preface,” pp. iii–iv. But Samuel M. Quincy is at least partly wrong, as the volume containing the Law Commonplace is identical in binding and paper page size (20.0 cm. by 16.1. cm.) to “Vol. 3” and “Vol. 4” containing the Reports, and is marked “Vol. 1.” There are also citations from the Reports to “Vol. 1” which clearly connect to the Law Commonplace substantively. So, at most, only one volume is missing. But there is a fourth volume, also of identical paper and page size (20.0 cm. by 16.1 cm.), which has a new cover. This is P 347 Reel 4 QP54. It is much thinner than the other three, and was dismissed by Samuel M. Quincy as “the fragment of another volume apparently just commenced.” It contained the “Middlesex Cases” (1771–1772) detailed at Reports, pp. 318–40, which were not in Quincy’s hand. Could it be the missing “Vol. 2”? Or a fragment of the volume? Most likely, Samuel M. Quincy was correct in dismissing the thin volume, but the identical paper and page size causes one to pause. Otherwise, “Vol. 2” was lost. It could have perished in the fire. A happier thought is that it may be discovered someday. What a fascinating find that would be.

35. See F. H. Lawson, The Oxford Law School 1850–1965 (Oxford, 1968), pp. 4–5 (hereafter, “Lawson”); Sutherland, supra, pp. 19–25. Lawson was certainly right in observing that “Blackstone exerted a greater influence in the North American colonies and subsequently in the United States than in England …” Lawson, p. 4. But both the theoretical style and the politics of his Commentaries earned Blackstone powerful enemies, such as Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson, writing to Madison in 1826, observed that when “the honied Mansfieldism of Blackstone became the student’s hornbook, from that moment, that profession (the nursery of our Congress), began to slide into toryism …” Thomas Jefferson, Works (P. L. Ford, ed., New York, 1905), vol. 12, pp. 455–56. See Sutherland, p. 13. Blackstone still has his pedagogical enemies. See Duncan Kennedy, “The Structure of Blackstone’s Commentaries,” 28 Buffalo Law Review 205 (1979). In addition, a good deal of the practiced legal training in England was outside both the Inns of Court and the universities, and remained more practical than formal. See David Lemmings, Professors of the Law, Barristers and English Legal Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2000), pp. 107–48.

36. Francis Stoughton Sullivan, A Plan For the Study of the Feudal and English Laws in the University of Dublin (Dublin, 1761), p. 4.

37. At least one thousand sets were exported to America before 1771, when a pirated edition was published in Philadelphia by Robert Bell. One thousand and four hundred copies were subscribed in advance, with one New York dealer taking two hundred and thirty-nine. See Sutherland, p. 25. Although Blackstone’s Commentaries were not available to Quincy when he began the Law Commonplace, he owned a set at his death in 1775. See Quincy’s Reports, Appendix 9, “Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Estate of Josiah Quincy Jun: Esq: Deceas’d,” Item 67. At least one volume of this set survived, for a time, in the library of Phillips Andover. It is now gone. Again, many thanks to Mark Sullivan, superb reference librarian. In addition, there is one citation to the first volume (1765) of Blackstone’s Commentaries at Law Commonplace, p. 94 [82], which may be a later addition, although apparently in Quincy’s hand. See page 281, n. 2, infra. There are several citations to Blackstone’s earlier Analysis of the Laws of England (Oxford, 1756). See Law Commonplace, pp. n.p. [6], n.p. [10] and 89 [77]. See also n. 46, infra.

38. See Carrington, supra, pp. 527‒38 and note 3 supra.

39. See John H. Langbein, “Blackstone, Litchfield, and Yale: The Founding of the Yale Law School,” History of the Yale Law School (ed. Anthony T. Kronman, New Haven, Conn., 2004), pp. 17–36. (Hereafter, “Langbein, The Founding.”)

40. Id., p. 30.

41. Id., p. 30.

42. Oxenbridge Thacher (1719–1765) was one of Boston’s most “eminent lawyers of the period.” See the biography set out in Appendix 6 to the Reports, vol. 5, infra. He was Quincy’s law tutor from 1763 to Thacher’s death in July, 1765. See Josiah Quincy, Memoir of the Life of Josiah Quincy, Jr. (2d ed., Boston, 1874), pp. 6–7. (Hereafter, “Memoir.”) See also Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduate, vol. xv: Biographical Sketches of Those Who Attended Harvard College in the Classes 1761–1763 (Boston, 1970), p. 479. On Thacher’s death in 1765, Quincy “took over the office and as much of the practice as he could handle.” Id., p. 479. According to John Adams, Thacher believed strongly in commonplacing. “He [Thacher] says He is sorry that he neglected to keep a Common Place Book when he began to study Law, and he is half a mind to begin now.” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 55 (October 25, 1758).

43. See, for example, the citation at Law Commonplace, p. 105 [transcript 90] to “Red Rep. 70 Angier v. Jackson.” That is a citation to Quincy’s “red” notebook, P347 Reel 4 QP55 (now rebound in brown), which contained the manuscript of his report of Angier v. Jackson, Reports, p. 84. As Samuel M. Quincy observed in his “Preface” to the Reports, this volume had “paper covers, (from the original color of which it is referred to as ‘Red Reports,’).” See Reports, p. iii. Quincy also cross-referenced the important case of Baker v. Mattocks at Law Commonplace, p. 106 [transcript 91]. Baker v. Mattocks was in the “Red Reports” at page 57, and in the Reports at page 69. I am most grateful to Kevin Cox, my brilliant research assistant, for deciphering these cross-references!

44. Hale’s Preface, n.p. [page 8].

45. Law Commonplace, Quincy n.p., Transcription p. [7].

46. Id., n.p., Transcription p. [9]. Quincy followed Reeve’s advice and relied on Wood’s Institute of the Laws of England for his preliminary “heads + divisions.” As J. L. Barton observed of Wood’s Institute, “Its success was certainly due in part to the fact that it was the only book of its kind in print until Blackstone’s Commentaries was published, but it is only fair to say that the tenth edition appeared as late as 1 7 7 2, when the Commentaries had been in circulation for some years.” J. L. Barton, “Legal Studies” in The History of the University of Oxford (ed. T. H. Ashton), vol. 5, The Eighteenth Century (eds. L. S. Sutherland, L. C. Mitchell, Oxford, 1986), p. 600.

The first volume of Blackstone’s Commentaries did not appear until 1765, and there is only one mention of it in Quincy’s Law Commonplace, which may be a later addition. See note 37 supra. There are several citations to Blackstone’s more rudimentary Analysis of the Laws of England [with] Introductory discourse on the Study of the Law (Oxford, 1756) and just preceding Reeve’s Directions to his Nephew, at Law Commonplace, Quincy n.p., Transcription, p. [6], but Quincy made little use of it, apparently preferring Wood’s “divisions” and Hale’s system. See further citations to Blackstone’s Analysis at p. n.p. [10] and p. 89 [77] of the Law Commonplace. John Adams was also aware of Blackstone’s Analysis, observing: “This day I am beginning my Ld. Hales History of the Common Law, a Book borrowed of Mr. Otis, and read once already, Analysis and all, with great Satisfaction. I wish I had Mr. Blackstone’s Analysis that I might compare, and see what Improvements he has made upon Hale’s.” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 169.

47. Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, pp. 54–55 (October 5, 1758). See also p. 32, infra, and accompanying note.

48. Id., p. 55. See also pp. 31–33, infra.

49. See Warren, pp. 175–76.

50. Langdell’s pioneering casebook on contracts contains not one word of explanatory text. To Langdell, the essence of study was to “select, classify and arrange all cases which had contributed to the growth, development, or establishment of any of its [contracts] essential doctrines.” C. C. Langdell, A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts (Boston, 1871), p. vii. In a sense, Langdell assisted with one aspect of commonplacing, the arrangement and sequence of cases, but continued to leave the student with the task of analysis and application. As Langdell noted: “Law, considered as a science, consists of certain principles or doctrines. To have such a mastery of these as to be able to apply them with constant facility and certainty to the ever-tangled skein of human affairs, is what constitutes a true lawyer; and hence to acquire that mastery should be the business of every earnest student of law.” Id., p. vi.

51. See Sutherland, pp. 92–139; Warren, History of Harvard Law School (New York, 1908), vol. 1, pp. 413–506.

52. See Coquillette, Joseph Story, supra, pp. 24–26. See also note 10, supra.

53. The Miscellaneous Writings of Joseph Story (ed. W. W. Story, Boston, 1852), pp. 380–81.

54. Newmyer, p. 40.

55. Id., p. 40.

56. Id., p. 40.

57. Id., pp. 41–42. For an account of the sparse early American law reporting, see Erwin C. Surrency, “Law Reports in the United States,” 25 Am. J. Legal Hist. 58 (1981); Alan V. Briceland, “Ephraim Kirby: Pioneer of American Law Reporting,” 16 Am. J. Legal Hist. (1972). There is an excellent book about early Supreme Court reports, Morris L. Cohen & Sharon Hamby O’Connor, A Guide to the Early Reports of the United States (1995). See also W. Hamilton Bryson, “Virginia Manuscript Law Reports,” 82 Law Libr. Jour. 305–11 (1990) and my case for Josiah Quincy’s claim as the first true American law reporter, Daniel R. Coquillette, “First Flower—The Earliest American Law Reports and the Extraordinary Josiah Quincy, Jr. (1744–1775),” 30 Suffolk Univ. L. Rev. 1 (1976), pp. 1–15 (hereafter, “Coquillette, Law Reports”).

58. Newmyer, p. 41.

59. Newmyer, p. 42.

60. Newmyer, p. 41.

61. Id., p. 44.

62. See Id., p. 41; Coquillette, Adams, pp. 360–76. As M. H. Hoeflich has observed: “During the period from the Revolution to the Civil War…. American lawyers were far less parochial than they were in the succeeding century. Many had a lively interest in Roman law and its descendent, the modern civil law. At the same time, this interest rarely became expertise.” M. H. Hoeflich, “An Aborted Attempt to Translate Justinian’s Digest in Antebellum America,” Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtgeschichte, 122 Band, p. 198 (Vienna, 2005).

63. Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, pp. 54–55 (October 25, 1758). Francis Dickins was the 16th Regius Professor of Civil Law at Cambridge, serving from 1714 to 1755, nearly 41 years!

64. Id., vol. 1, pp. 173–74. See also vol. 1, p. 199. By “Vinnius,” Adams was referring to Arnoldus Vinnius (1586–1657), whose popular commentary on Justinian’s Institute, In Quattuor libros institutionum imperialium commentarius academicus was to be found in many eighteenth-century editions, such as the Venice edition of 1736. These were usually edited by Johann Gottlieb Heineccius (1681–1741). Johannes Van Muyden, a civilian scholar, lived from 1652 to 1729. His Compendiosa institutionum Justiniana tractatie was eventually acquired by Adams from Gridley’s library and remains today in the Boston Public Library. See Adams, Diary, supra, vol. 1, p. 57, n. 2. See also p. 27, supra, and accompanying notes.

65. These extraordinary similarities were first noticed by my talented research assistant, Kevin Cox, Harvard Law School 2006. Dickins’s program was not too strenuous! According to the letter copied into Quincy’s notebook, “If a general knowledge only of the Civil Law is desired in the most short and compendious Method, the most advisable way is to read Wood’s Institutes [Thomas Wood, A New Institute of the Imperial or Civil Law (London, 1704), with subsequent editions in 1712, 1721, and 1730] in its natural order, translated into English by W. Strahan: [Jean Domat, Civil Law in its Natural Order (trans. William Strahan, London, 1722), with subsequent printings in 1737 and 1772]. [T]hese two authors will furnish a careful reader with the main principals [sic] of the Civil Law in all its several branches.” “Vol. 4” P347, Reel 4, QP58, p. 148. Only if “the intent be to become as compleat a master as may be of the Civil Law” was it “necessary to begin with the first Element and to read Justinian’s Institutions …” Id., p. 148. In short, no need for a gentleman to actually read law from the original sources to have “a general knowledge of the civil law”! This rather cavalier approach was reflected in other “quick and easy” civil law guides of the period, some of which were cross-cited to Blackstone’s Commentaries. See, for example, the short book by one of Dickins’s successors as Regius Professor, Samuel Hallifax, who served from 1770 to 1782. Hallifax’s An Analysis of the Roman Civil Law (Cambridge, 1774) was extensively cross-referenced to Blackstone, and was certainly not “heavy lifting,” even by the standards of modern student “outlines”! Certainly no Latin was required. Quincy’s laborious collection of Latin maxims was not a Roman Law course, but it involved much more effort and familiarity with original Latin sources than the “courses” of civil law Dickins and Hallifax prepared for the “gentleman scholar” of Cambridge in the eighteenth century!

66. “There was a continuing tradition in England of small books purporting to assist law students by isolating the ‘principal grounds and maxims’ of the law. This tradition went back to Abraham Fraunce’s (1557?–1633) The Lawyiers Logick (1588), a book designed to introduce Fraunce’s fellows at Gray’s Inn, which included Bacon, to the Ramis dialectic. Indeed, the tradition could be said to include St. Germain’s Doctor and Student, as early as 1523, where the ‘Student of the Common Law’ invoked ‘dyvers pryncyples that be called by those learned in the lawe maxymes … for every one of those maxymes is suffycyent auctorytie to hym selfe to such an extent that it is fruitless to argue with those who deny them.’ The maxims in St. Germain’s book were apparently the basis of the first English collection of maxims, Principia sive Maxima Legum Anglie (London, 1546) located and described in a most scholarly study by John C. Hogan and Mortimer D. Schwartz. There followed books like William Fulbeck’s (1560–1603) A Direction or Preparative to the Study of the Lawe (1600) (Fulbeck being another Gray’s Inn lawyer), Sir Henry Finch’s (1558–1625) Nomotechnia (1613), and William Noy’s (1577–1634) A Treatise of the Principall Grounds and Maximes of the Lawes of this Kingdome (1641). The latter was a treatise written originally in Law French and published in English long after the author’s death. It remains difficult to show when any of these little treatises was first written and circulated at the Inns of Court. It is therefore hard to prove the exact sequence of ideas between them, and from them to Bacon.” Daniel R. Coquillette, Francis Bacon (Stanford, 1992), p. 37 (hereafter, “Coquillette, Bacon”).

67. Id., pp. 37–38.

68. Id., p. 39.

69. Id., p. 39.

70. Id., p. 40.

71. Reports, p. 209.

72. Reports, p. 201.

73. Coquillette, Bacon, p. 39, citing Bacon’s Maximes (1631), Works of Francis Bacon (ed. J. Spedding, R. L. Ellis, D. D. Heath, London, 1857–74), vol. VII, p. 321. (Hereafter, “Works of Francis Bacon.”)

74. As to “the comparison of legal systems to discover universal rules when they existed” and its importance to Joseph Story and other American lawyers of the early Republic, see M. H. Hoeflich, “Comparative Law in Antebellum America,” 4 Washington University Global Studies Review 535, 537–44 (2005). Bacon compared maxims to a ‘magnetic needle’ that “points at the law, but does not settle it.” Works of Francis Bacon, vol. XIII, p. 67. “The magnetic needle was useful because it accurately reflected the natural phenomenon of the earth’s polarity. Likewise, useful jurisprudence began with the empirical facts of the law that existed in the courts and the statute books, and then moved, step by step, to generalities that were genuinely useful, because they were a product of induction from reality. But it was also already plain that Bacon’s maxims were intended to do more than simply describe and restate existing law. By accurately identifying the rational, consistent and systematic ‘middle axioms’ of the system, the development of the law could be directed toward more harmony and more reason.” Coquillette, Bacon, p. 46.

75. “Mr. Otis reasoned with great learning and zeal …” Adams, Diary, vol. 1, p. 267 (Dec. 20, 1768).

76. Reports, p. 203.

77. C. C. Langdell, A Selection of Cases on the Law of Contracts (Boston, 1871), p. vi.

78. Matthew Hale talked of a seven-year period, or longer, for the commonplacing process. “Touching the Method of the study of the Common Law, I must in general say thus much to the Student thereof; It is necessary for him to observe a Method in his Reading and Study; for let him assure himself, though his memory never be so good, he shall never be able to carry on a distinct serviceable Memory of all, or the greatest part he reads, the end of seven years, nor a much shorter time, without the helps of Use or Method; yea what he hath Read seven years since, will, without the help of Method, or reiterated use, be as new to him as if he had scarce ever read it: A Method therefore is necessary, but various, according to every Man’s particular Fancy …” Matthew Hale, “Preface Directed to the Young Students of the Common Law,” in Henry Rolle, Un Abridgment Des Plusieurs Cases … del Common Ley … (London, 1668), n.p.

79. See Coquillette, Law Reports, pp. 1–15.

80. See Mary Sarah Bilder, The Transatlantic Constitution: Colonial Legal Culture and the Empire (Cambridge, Mass., 2004), pp. 1–11. (Hereafter, “Bilder.”)

81. The Charters and General Laws of the Colony and Province of Massachusetts Bay (Boston, 1814), The Charter of the Province … (1691), pp. 31–33. (Hereafter, “Charters and General Laws.”) It is interesting to note that oaths had to be “not repugnant to the laws and statutes of this our realm of England.” Id., p. 33 (emphasis added). Was the omission of “and statutes” from the general power to make law significant? Could colonial statutes conflict with individual English statutes, but not with the common law itself?

82. Id., p. 32.

83. See, for example, the discussion and the refusal to grant an appeal in Scollay v. Dunn, Case 30 (1763), Reports, pp. 80–83.

84. See Morton J. Horwitz, The Transformation of American Law, 1780–1860 (Cambridge, Mass.), p. 17 (hereafter, “Horwitz”). See also Bilder, pp. 35–40.

85. See, for example, Hanlon v. Thayer Case 37 (1764), Reports, pp. 99–103, where Chief Justice Hutchinson remarked, “I should have been extremely glad if this case had been argued a little more largely by the Gentlemen of the Bar, and more Authorities cited, in Matter of so great Consequence.” Id., p. 102.

86. See, for example, the discussion in the important case of Banister v. Henderson (Case 42, 1765) at pp. 122–45. At one point, Quincy questioned Gridley’s argument, noting, “Sed quaere, and see Dr. Sullivan’s Lect. On the Laws of England 182, 3 [published as F. S. Sullivan, Lectures on the Constitution and Laws of England etc. (London, 1770)], and Qu. If ye Act of Parliament extends, or is binding here.” Id., p. 145. (Quincy’s note must have been added after the case report.) In the same case, Chief Justice Hutchinson again admonished the bar, “Have you no Authorities, Gentlemen?” to have Gridley reply, “There is no Authority that the Sun shines.” Id., p. 122.

87. Appeals “to his Majesty in Council” were not allowed in major cases such as Dudley v. Dudley Case 9 (1762), apparently because the Charter of 1691 allowed appeals in “personal” actions only and not land cases. See Reports, p. 25, Charters and General Laws, supra, p. 32. Cases that directly presented conflicts between English and colonial law, such as Bromfield v. Little Case 40 (1764), Reports, p. 108, although of “much Importance to the Community,” were not appealed, possibly because the monetary requirement of the Charter was not met. See also the discussion in Scollay v. Dunn Case No. 30 (1763), where leave to appeal was denied. Reports, pp. 80–83.

88. See, for example, Baker v. Frobisher Case 2 (1761) on “unmerchantable soap” where the justices distinguished between ordinary retail sales and bulk sales sold “by sample.” Reports, p. 4.

89. Horwitz, supra, p. 4.

90. See Southern Journal (1773), p. 61, and accompanying notes, and its introduction, “An Odyssey of America on the Brink of Revolution,” Quincy Papers, vol. 3, pp. 52–58.

91. Id., p. 61, and accompanying notes.

92. See the references to the Analysis at the beginning of the Law Commonplace, p. n.p., [6], p. n.p., [10], and at “Of Statutes or Acts,” id., p. 89 [77]. The sole reference to Blackstone’s Commentaries is at p. 94 [82], and may be a later addition. See notes 37, 46, supra.

93. Horwitz, supra, p. 4.

94. Id., p. 30.

95. Horwitz quotes the 1817 lectures of Tapping Reeve and James Gould at the Litchfield Law School: “Theoretical[ly] courts make no law, but in point of fact they are legislators.” Horwitz, p. 23. Horwitz regarded Blackstone’s “dichotomy between the nature of the two forms of law” as “a fairly recent creation,” noting that Coke in deciding Calvin’s Case in 1608 did not make the distinction. “[T]here was no suggestion of a distinction between statute and common law, for statutes were still largely conceived of as an expression of customs.” Id., p. 17. But, Horwitz argued, in the period “[b]efore the American Revolution common law and statute law were conceived of as two separate bodies of law, and the authority of judges and legislators was justified in terms of the special category of law that they administered.” Id., pp. 16–17.

96. Bilder, supra, p. 91.

97. See Law Commonplace, pp. 25 [30], 47 [45], 49 [47].

98. See Id., pp. 22 [27], 176 [119].

99. See Id., p. 179 [122].

100. See Id., p. 181 [124].

101. See Id., p. 176 [119].

102. Quincy’s Law Commonplace made no mention of the Massachusetts provincial statute William & Mary 4 (1692) “An Act for the Settlement and Distribution of the Estate of Intestate,” Charters and General Laws (Boston, 1814), Chapter 8, pp. 230–32, which established part-ibility in the colony, rather than primogeniture! See, in contrast, Dudley v. Dudley Case 9 (1761), p. 12; Elwell v. Pierson Case 20 (1762), p. 42; Baker v. Mattocks Case 29 (1763), p. 69; and Banister v. Henderson Case 42 (1765), p. 119.

103. See Law Commonplace, pp. 47 [45]–49 [47].

104. See William & Mary 4 (1692), Charters and General Laws, supra, pp. 230–32.

105. See cases cited at note 102, supra.

106. Unlike his Reports, Quincy’s Law Commonplace simply copied in the traditional English law under the “Of Lands, Tenements + Hereditaments” caption, taking it mostly from Thomas Wood’s An Institute of the Laws of England (1st ed., London, 1720), book 2, chap. 3, pp. 228–30. See Law Commonplace, page [7], note 3, infra. Thus he writes: “In short, Lands + Tenements in Fee-s: Descend, 1st to the eldest son or Heir + to his issue: The sons first in order of birth + for want of sons to all the Daughters equally,” although that was not the law in Massachusetts. The section “Of Estates” in the Legis Miscellanea also simply reproduces English common law, but focuses instead on the more difficult Coke on Littleton (London, 1628) and William Hawkins, Abridgment of Coke on Littleton (London, 1711). See vol. 4, pp. 5–10, infra, and accompanying notes, and pp. [24], n. 9, [68], n. 6.

107. Law Commonplace, p. 48 [46].

108. Id., p. 48 [46].

109. See note 102, supra.

110. Law Commonplace, Index “Legis Miscellanea,” p. 179 [122].

111. See, for example, Duncan Kennedy’s “How the Law School Fails,” 1 Yale Rev. of Law and Social Action 71 (1970), Mark Tushnet, “Critical Legal Studies: A Political History” 100 Yale L.J. 1515 (1991), and the discussion in Laura Kalman, “The Dark Ages,” in History of the Yale Law School (A. T. Kronman, ed., New Haven, 2004), pp. 203–06.

112. Law Commonplace, p. 20 [25].

113. See Law Commonplace, p. 20 [25], n. 4. See also Ferdinand Pulton, A Collection of Sundrie Statutes (London, 1632), p. 401.

114. Law Commonplace, p. 20 [25].

115. Id., p. 20 [25].

116. Id., pp. 20 [25]–21 [26].

117. Id., p. 21 [26].

118. See Id., p. 152 [95] (medicine). See also Reports, Dom. Rex v. Doaks Case 34 (1763), p. 90 (bawdy house); Dom. Rex v. Pourkdorff Case 38 (1764), p. 104 (theft).

119. Law Commonplace, p. 21 [26].

120. Id., p. 152 [95], n. 8, see also p. 16 [21].

121. Id., p. 152 [95].

122. Id., p. 27 [32]. “N.A.” is for “non-assumpsit,” “she did not promise.” This was the standard plea by way of traverse denying the existence of an express promise “or of matter of fact from which the promise alleged would be implied by law, and thus raised to general issue.” Earl Jowitt, The Dictionary of English Law (ed. C. Walsh, London, 1 9 5 9), p. 1 2 3 1. (Hereafter, “Jowitt.”)

123. Id., p. 27 [32], n. 5.

124. Id., p. 27 [32].

125. Id., p. 21 [26].

126. Id., p. 27 [32].

127. Id., p. 22 [27]. Where the property taken is in the form of personal chattel or “choses in action” (monetary legal claims), the result can be complicated! See id., p. 22 [27].

128. See David M. Walker, The Oxford Companion to Law (Oxford, 1980), p. 327.

129. See Bilder, supra, pp. 96–97.

130. Law Commonplace, p. 23 [28].

131. See the full discussion in Coquillette, Law Reports, supra, pp. 23–25.

132. Chief Justice Hutchinson observed that it would “have been better to have brought Detinne.” Reports, p. 103. He was right. “Trover” was the correct action for wrongful deprivation of goods, where the remedy was “damages merely,” i.e., money. Jowitt, supra, p. 1785. “Detinue” was the correct action for “a plaintiff who seeks to recover goods in specie [i.e., the actual thing], or on failure thereof the value …” Id., p. 623. Assuming the plaintiff wanted her actual clothes back, she should have sued in detinue.

133. See the excellent paper by Sally Ann Carter, Harvard Law School Class of 1997, “An Exploration of Hanlon v. Thayer,” pp. 21–22, on file with the author.

134. Id.

135. Reports, p. 102.

136. Id., p. 102, n. 6.

137. Id., p. 102.

138. Id., pp. 102–03 (note omitted).

139. Id., p. 103.

140. Id., p. 163.

141. Id., pp. 162–63. See “An Act to Prevent the Destroying and Murdering of Bastard Children,” Gul. III, 8 (1696), Chap. 38, Charters and General Laws, supra, p. 293.

142. Reports, p. 163.

143. Id., p. 121.

144. Id., p. 123.

145. Id., p. 124.

146. Law Commonplace, pp. 156 [99], 174 [117].

147. See discussion at note 102, supra.

148. See Law Commonplace, “Legis Miscellanea,” p. 161 [104].

149. See Law Commonplace, p. 179 [122]. See also id., at pp. 155 [98], 159 [102], 165 [108], 171 [114], 172 [115].

150. See, for example, Reports, Allison v. Cockran, Case 36 (1764), p. 94 (“trover for a negro”) and Oliver v. Sale (Case 13, 1761), p. 29 (suite for selling “two free Mulattos for Slaves”).

151. Id., p. 106 [91]. See, for example, “An Act to Prevent Disorders in the Night” which prohibited an “Indian, negro or mulatto servant or slave” from being “abroad in the night time after nine o’clock unless it be upon some errand for their respective masters or owners” (October, 1703). Charters and General Laws, supra, pp. 746–49. “Fornication” between the races was prohibited and if “any negro or mulatto shall presume to smite or strike any person of the English, or other Christian nation, such negro or mulatto shall be severely whipped …” (October, 1705), id., pp. 747–48.

152. Case No. 28 (1763), Reports, p. 67.

153. Law Commonplace, p. 15 [20].

154. Id., p. 15 [20].

155. Id., p. 15 [20].

156. Id., p. 16 [21].

157. Id., p. 14 [19].

158. Id., p. 15 [20].

159. Id., p. 15 [20].

160. Id., p. 15 [20].

161. Henry Sumner Maine, Ancient Law (1st American from 2d English ed., New York, 1864), pp. 295–96. (Maine used the male pronoun, ironically appropriate for 1864.)

162. See the Southern Journal (1773), infra, pp. 91–95, 109–10, 113–14.

163. Law Commonplace, p. 44 [42].

164. Id., p. 44 [42]. Quincy was using “equity” in the sense of “fairness.” Juries were not used in “equity” cases, in the legal sense, such as “equity” cases in Chancery. See Jowitt, supra, pp. 724–26.

165. Law Commonplace, p. 58 [55].

166. Id., p. 58 [55].

167. Id., p. 50 [48].

168. Id., p. 51 [49] (Lilly again).

169. Id., p. 52 [50].

170. Id., p. 46 [44] (emphasis in original).

171. Id., p. 45 [43].

172. See id., p. 51 [49], n. 6. A copy of Catharine Macaulay’s History was in Quincy’s estate at his death. See Reports, Quincy Papers, Volume 5, Appendix 9, item 230.

173. Id., p. 51 [49] (emphasis in the original).

174. Id., p. 44 [42].

175. Id., p. 52 [50]. See also p. 44 [42] as to attaint, already an archaic remedy in Quincy’s day. See William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England (Oxford, 1768), vol. 3, p. 404, pp. 3 8 9–9 3. Attaint at English law was abolished by the Juries Act, 1 8 2 5, S. 6 0. See Jowitt, supra, p. 1 1 4.

176. Law Commonplace, p. 44 [42].

177. Id., p. 44 [42].

178. Id., p. 44 [42].

179. Id., p. 45 [43].

180. Id., p. 60 [57] (emphasis in original).

181. Id., p. 61 [58] (emphasis in original).

182. See Adriaan Lanni, “Verdict Most Just: The Modes of Classical Athenian Justice,” 16 Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 227 (2004).

183. Reports, pp. 189–90.

184. Id., p. 191.

185. Id., p. 193.

186. Id., p. 118.

187. Id., p. 118.

188. Id., p. 50.

189. Id., p. 85. But attaint was an archaic remedy by this time. See n. 175, supra, and text below, infra.

190. Id., p. 85.

191. The issue was recently revisited by the Supreme Court of the United States in Gasperini v. Center for Humanities, Inc., 518, U.S. 415 (1996). This author, together with a group of legal scholars including Akhil Reed Amar, Erwin Chemerinsky, Arthur F. McEvoy, and Arthur R. Miller, filed an amicus brief supporting the power of the jury at common law. The majority of the court were unconvinced, but a powerful dissent by Justice Scalia, joined by Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice Thomas, observed that “the court frankly abandons any pretense at faithfulness to the common law, suggesting that ‘the meaning’ of the Reexamination Clause was not ‘fixed at 1791,’ contrary to the view of all our prior discussions …” 518 U.S. 415, at 461 (citation omitted). See Coquillette, “Law Reports,” Quincy, Works, vol. 4.

192. See id., at pp. 12–15. See also David L. Shapiro & Daniel R. Coquillette, “The Fetish of Jury Trial in Civil Cases: A Comment on Rachal v. Hill,” 85 Harv. L. Rev. 442, pp. 228–55 (1971), cited with approval in Parklane Hosiery Co. v. Shore, 439 U.S. 322, 333, arguing 1791 as the appropriate date for assessing common law jury rights for Seventh Amendment purposes.

193. Law Commonplace, p. 51 [49]. See id., p. 51 [49], n. 8 on Plowden’s Commentaries.

194. Law Commonplace, p. 50 [48].

195. Id., p. 50 [48].

196. Id., p. 51 [49], Relying on Lilly’s Abridgment (London, 1719). See id., p. 50 [48], n. 3.

197. See Reports, supra, pp. 382–83, 385.

198. See “Of Statutes or Acts,” Law Commonplace, pp. 89 [77]–97 [85].

199. See Bilder, supra, pp. 2–7, 40–46, 55, 104–07.

200. Law Commonplace, p. 64 [60]. Montesquieu also was extracted in Quincy’s Political Commonplace. See Quincy Papers, vol. 1, p. 109.

201. Id., p. 65 [61].

202. See John C. Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (Stanford, rev. printing, 1959), pp. 109–46.

203. Reports, p. 201.

204. Id., p. 204.

205. Law Commonplace, p. 65 [61].

206. Id., p. 64 [60].

207. Id., p. 65 [61].

208. Reports, pp. 203–04. Otis’s “first principle” was a translation of the opening of Justinian’s Institutes, also quoted at the outset of the great English treatise, Bracton.

209. Id., pp. 205–06.

210. See Law Commonplace, p. 63 [59], n. 2, (Montesquieu); p. 65 [61], n. 2, (Burlamaqui); p. 65 [61], n. 4, (Hobbes); p. 65 [61], n. 5, (Vattel); p. 67 [63], n. 2, (Bacon) and (Beccaria); p. 67 [63], n. 3.

211. Id., p. 89 [77].

212. Id., p. 89 [77].

213. See discussion at notes 37 and 46, supra.

214. Law Commonplace, p. 89 [77].

215. Id., p. 91 [79].

216. Id., p. 91 [79].

217. Id., p. 91 [79].

218. 5 U.S. (1 branch) 137 (1803) (Marshall, C. J.)

219. 8 Coke’s Reports (London, 1611), p. 114a. Coke suggested “that in many cases, the Common Law will control Acts of Parliament, and sometimes adjudge them to be utterly void….” Id., p. 118a. See Daniel R. Coquillette, The Anglo-American Legal Heritage (2d ed., Durham, N.C.), pp. 318–19, 342. See also S. E. Thorne, “Dr. Bonham’s Case,” 54 L.Q. Rev. 543–52 (1938); C. M. Gray, “Barnham’s Case Revisited,” (1972) 116 Proc. American Philosophical Society, pp. 35–58 and T. F. T. Plucknett, “Bonham’s Case and Judicial Review,” Studies in English Legal History (London, 1985), pp. 33–70.

220. Law Commonplace, p. 93 [81].

221. Id., p. 93 [81].

222. Id., p. 93 [81] (almost an exact quote).

223. Id., p. 95 [83].

224. Id., p. 95 [83] (emphasis in original).

225. Id., p. 96 [84] (emphasis in original).

226. Id., p. 97 [85].

227. Id., p. 97 [85] (emphasis in original).

228. See Fuller’s classical parable of statutory construction and application, “The Case of the Speluncean Explorers,” 62 Harv. L. Rev. 616 (1949).

229. Reports, p. 38.

230. Id., pp. 38–39.

231. Id., p. 39.

232. Id., p. 40.

233. Id., pp. 40–41.

234. Id., pp. 387–88, n. 2. Auchmuty was suggesting that the Freemason was looking for an opportunity to smuggle the wine ashore, i.e., “running” as in “rum runner.”

235. Id., pp. 388–89.

236. Id., pp. 390–91.

237. Id., p. 393.

238. Id., pp. 382–83.

239. Id., p. 385.

240. Id., p. 385.

241. Id., p. 386 (emphasis in original). “Printed in the Boston Gazette (Edes & Gill) Monday, May 20, 1771.”

242. Law Commonplace, p. 42 [40].

243. Id., p. 72 [64], Legis Miscellanea, p. 150 [93], p. 154 [97].

244. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 154 [97].

245. Id., p. 18 [23], p. 29 [33].

246. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 153 [96], pp. 162 [105]–164 [107].

247. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 153 [96].

248. Id., p. 11 [16].

249. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 158 [101].

250. Id., Legis Miscellanea, pp. 152 [95]–158 [101].

251. Id., p. 25 [30]. See also “Notebook 4,” p. 5.

252. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 170 [113].

253. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 154 [97].

254. Id., p. 47 [45].

255. Id., p. 53 [51], Legis Miscellanea, p. 153 [96], p. 163 [106].

256. Id., p. 81 [71].

257. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 162 [105].

258. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 167 [110].

259. Id., p. 98 [86], Legis Miscellanea, pp. 166 [109]–167 [110].

260. Id., p. 151 [94], p. 153 [96].

261. Id., p. 12 [17].

262. Id., Legis Miscellanea, pp. 158 [101], 167 [110], 170 [113].

263. Id., Legis Miscellanea, pp. 150 [93]–151 [94], 153 [96]–154 [97], 157 [100], 159 [102], 161 [104], 163 [106], 166 [109].

264. Id., Legis Miscellanea, p. 150 [93].

265. Volume 5, Appendix, will also contain the “Catalogue of Books Belonging to the Estate of Josiah Quincy Jun: Esq: Deceas’d” (1775), an exceptionally valuable reference given Quincy’s sudden death in mid-career.

Page [1]

1. “pretium” = “price” (Latin). Did Quincy pay “20 shillings, nine pence” for this notebook, or for a set of four leather-bound notebooks? See the discussion at “Introduction: The Legal Education of a Patriot: Josiah Quincy Jr.’s Law Commonplace (1763), Section 1, The Manuscript,” supra, p. 12. See also Illustration 1.

2. Quotation is loosely from Coke’s Reports, vol. 10 (covering 1572‒1616), p. 139b. “Salus Populi est Suprema Lex.” Translation of Quincy’s text: “The welfare of the people, or of the public, is supreme law.” (E. H. Jackson, Latin for Lawyers, London, 1915, p. 241.) The first edition of Sir Edward Coke’s Reports, in English, was published in London in 1658. The first volume of Coke’s Reports in French had been published in 1600. Subsequent English editions were produced in 1680, 1727, 1738, 1793, 1797, and 1826. See Sweet and Maxwell’s Legal Bibliography, vol. 1, pp. 295‒97 (2nd ed., London, 1955; hereafter, Sweet & Maxwell).

3. The quote, “From law arises security, from security curiosity. And from curiosity knowledge. The latter steps of this progress may be more accidental; but the former are altogether necessary,” is nearly identical to a passage of David Hume’s essay, “Of the Rise and Progress of the Arts and Sciences,” which appeared in 1742 in Volume 2 of Hume’s Essays, Moral and Political. The version online, at http://rit.minsk.by/cgi-bin/showtext.pl/Philosophy/1700-1799/hume-of-737.txt-ps50-pn1, was based on the 1875 Green and Grose edition of the essays. The only differences between the quote above and Hume’s passage are some minor punctuation differences. Many thanks to my excellent research assistant, Brian Sheppard, Boston College Law School, 2001.

Page [2]

1. Loose copy of Edward Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (hereafter by its common name, “Coke on Littleton”), p. 9a.

2. Loose copy of Coke on Littleton, p. 64b. Translation of Latin: “Six hours in sleep and you should give just as much equally to the laws, you will pray for four hours, and give two to letters. What is left over you should bestow upon the singing of sacred songs.”

3. Loose copy of Coke on Littleton(1st ed., London, 1628), p. 70b. Quincy’s note, “top,” is correct for early editions. Translation of Latin: “The unreasonable reading and the hasty reaction.”

4. Copied from Lord H. H. Kames’s two-volume Historical Law Tracts (1st ed., Edinburgh, 1758), vol. 2, p. 128. See Sweet & Maxwell, vol. 1, p. 34.

Page [3]

1. Translation of Latin: For “no element in its own place is heavy.”

2. Loose copy, with some omissions, of Coke on Littleton (1st ed., London, 1628), p. 71a. Quincy’s note, “bot.” or “bottom,” is accurate for early editions.

Page [4]

1. Loose copy of Coke’s Reports, vol. 1, “The Preface to the Reader,” n.p. (1st ed., London, 1600). The exact text from Coke reads:

For reading without hearing is darke & yrckeſome, and hearing without reading is flippery and vncertaine, neither of them truly yeeld ſeaſonable fruit without conference, without meditation & recordation, nor all of them together without due and orderly obſervation, scribe ſapientiam tempore vacuitatis tuæ, faith Salomon. And yet he that at length by theſe meanes ſhall attaine to be learned, when he ſhal leaue them off quite for his gaine, or his eaſe, ſoone ſhal he (I warrant him) looſe a great part of his learning, Therefore as I allow not to the Student any diſcontinuance at all (for he ſhal looſe more in a moneth then he ſhal recover in many:) So do I commend perſeverance to all, as to each of theſe means an inſeperable incident.

The Latin phrase is adapted from the Vulgate, specifically the Biblical Book of Sirach, or Ecclesiasticus, Chapter 38, verse 25: “Write wisdom in the time of your leisure.”

Page [5]

1. This is a loose copy, with some omissions, of Coke on Littleton, pp. 11a–11b. Quincy does not follow the punctuation of Coke’s 1st edition, although he may be copying from a later edition. He also omits Coke’s translations of Latin terms in some places. See notes 2 and 3, below.

2. Coke translated this “from approved Precedents and Use,” Id., p. 11a. Quincy omits this translation, and those following in notes 3‒9, below.

3. Coke translated this “from not use.” Id., p. 11a.

4. Coke translated this “artificial arguments consequents and conclusions.” Id., p. 11a.

5. Coke translated this “from the common opinion of the sages of the law.” Id., p. 11a.

6. Coke translated this “from that which is inconvenient.” Id., p. 11a.

7. Coke translated a divisione, “from a division,” and vel ab enumeratione partium, “from the enumeration of the parts.” Id., p. 11a.

8. Coke translated this a maiore ad minus, “from the greater to the lesser” or “from the lesser to the greater.” Id., p. 11a. Coke does not translate a simili, a pari: “from the similar, from the equal” (i.e., reasoning by analogy).

9. Coke translated this “from that which is impossible.” Id., p. 11a.

Page [6]

1. Coke translated this “from the end.” Coke on Littleton, p. 11a. Quincy omits this translation, and those following in notes.

2. Coke translated this “from that which is profitable or unprofitable.” Id., p. 11a.

3. Here Quincy copies Coke’s translation at Id., p. 11a. Perhaps he felt Coke’s words added more substance to the straight Latin translation for “quasi a surdo prolatum.”