FEBRUARY MEETING, 1919

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held at the house of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, No. 28 Newbury Street, Boston, on Thursday, 27 February, 1919, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the President, Fred Norris Robinson, Ph.D., in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

The Corresponding Secretary reported the death of two Resident Members — Horace Everett Ware on the twenty-seventh of January, and the Rev. Henry Ainsworth Parker on the seventeenth of February.

He also reported that letters accepting Resident Membership had been received from Mr. Charles Rockwell Lanman and Mr. Henry Goddard Pickering.

Mr. Robert Gould Shaw of Wellesley was elected a Resident Member.

Mr. George L. Kittredge paid a tribute to the memory of Mr. Ware, and read the following paper which had been prepared by Mr. Ware for presentation at this meeting:

ADDITIONAL NOTE ON THE PERIODICAL CICADAS

In my Note on the Periodical Cicadas,676 I made reference to The Periodical Cicada by C. L. Marlatt, now Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Entomology, United States Department of Agriculture.677 This is a comprehensive and lucid treatise on this most interesting insect. The Bulletin contains 181 pages and has maps and other illustrations.

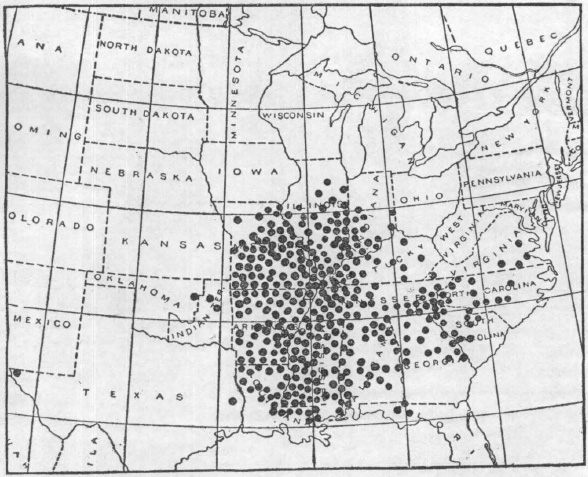

There are two races of periodical cicadas, — the seventeen-year race and the thirteen-year race. In the Bulletin the broods occurring in the different years are severally designated by Roman numerals. Taking the different broods together, this cicada is known to occur pretty generally within the United States east of Central Kansas and north of the peninsular portion of Florida. No broods, however, have been found in northern New England except a doubtful record in Vermont, nor west of the Mississippi above Iowa. Two maps showing the distribution of the broods of the 13-year race and the 17-year race respectively, are here reproduced facing page 282 from pages 36 and 37 of the Bulletin. The 13-year broods are mostly in the Southern States, the bulk of them in the States adjoining the Mississippi River from northern Missouri and mid-Illinois southward. Very few of the 17-year broods are found south of Tennessee and North Carolina. Swarms belonging to a single brood in some cases inhabit widely separated areas.

I have received a letter from Mr. Marlatt under date of November 8, 1918, acknowledging the receipt of a copy of my Note on the Periodical Cicadas. In the course of his letter Mr. Marlatt says:

The record made by Winthrop in 1648 very probably has no connection with the Plymouth swarm; at any rate, the inference apparently is much stronger that it refers to Brood XI which occurs chiefly along the Connecticut River Valley in Massachusetts and Connecticut. The record which you quote was unknown to me or I should have suggested the assignment to this record rather than to the appearance of the Plymouth brood of 1651.

The correctness of the date of the first appearance of the Plymouth brood in 1633 seems to be well supported by the evidence which you have produced. In that event, subsequent to that period there must have been some extraordinary climatic condition of excessive cold which belated this brood in one of its 17-year periods one year, giving it for that period an 18-year cycle. It is on the theory of such retardations and accelerations that the periodical Cicada has been broken up into the numerous broods which now characterize it, and hence this particular evidence is significant and interesting and also corroborative of this theory.

The Plymouth brood or swarm comes under Brood XIV in Marlatt’s Periodical Cicada. I quote the following from his account of that brood:

No published records have been found of the later appearances [than 1633–1634] prior to 1789, but definite records have been made of each return since that year. An interesting account of the last appearance (1906) of the Cicada in Plymouth County is given in a report received from Martha W. Whitmore, Chiltonville, Plymouth, Mass. The near-by Barnstable colony was also most abundant last year (1906) all along Cape Cod. As reported by Miss Grace Avery, of Washington, D. C, the ground along the coast was covered with the dead bodies and the trees in the forests were all fired and brown from the egglaying of the females.

Prof. H. T. Fernald reports (letter September 26, 1906) the distribution in Plymouth and Barnstable counties as in the following towns: Plymouth, Wareham, Bourne, Falmouth, Sandwich, Mashpee, Barnstable, Yarmouth, and Dennis, being most abundant in the three first named.

This brood, like Brood VI, covers a very wide range, extending from Massachusetts westward to Illinois, with important groups of swarms extending from Pennsylvania southward into northern Virginia and in the Lower Alleghenies, covering portions of North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, etc., and in the Ohio Valley region, covering especially southern Ohio, Indiana, central Kentucky, and western West Virginia.678

The next appearance of Brood XIV is expected in 1923

The record made by Winthrop in 1648 referred to in Mr. Marlatt’s letter is under date of August 15, 1648, and is as follows:

About the midst of this summer, there arose a fly out of the ground, about the bigness of the top of a man’s little finger, of brown color. They filled the woods from Connecticut to Sudbury with a great noise, and eat up the young sprouts of the trees, but meddled not with the corn. They were also between Plymouth and Braintree, but came no further. If the Lord had not stopped them, they had spoiled all our orchards, for they did some few.679

As stated in the extract from his letter quoted above, Mr. Marlatt inclines to the opinion that the swarm told of by Winthrop belongs rather to Brood XI than to that of the Plymouth swarm, Brood XIV.

MAP SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE BROODS OF THE 13-YEAR RACE

MAP SHOWING THE DISTRIBUTION OF THE BROODS OF THE 17-YEAR RACE

from u. s. department of agriculture. bureau of entomology. bulletin no. 71, figs, 2, 3

engraved for the colonial society of massachusetts

According to the seventeen-year succession the Winthrop brood after 1648 would be expected to appear in the following years: 1665, 1682, 1699, 1716, 1733, 1750, 1767, 1784, 1801, 1818, 1835, 1852, 1869, 1886, 1903, 1920. Mr. Marlatt’s account of Brood XI has such pertinence in this connection that I quote it in full omitting the map (Fig. 14) accompanying the text:

Brood XI — Septendecim — 1920. (Fig. 14.)

This is a small brood limited, for the most part, to the valley of the Connecticut River in the States of Massachusetts and Connecticut, with one colony in the vicinity of Fall River separated from the main swarm. It is Brood I of Walsh-Riley and Brood 9 of Fitch, who reports it as having occurred in 1818 and 1835. It was recorded also by Dr. Gideon B. Smith from 1767 to 1852, and the genuineness of the brood was fully established in 1869. Like most small broods in settled regions, it is being greatly reduced in numbers, and in 1903 Mr. Britton reports680 that he was not able to secure any records for Connecticut, although special effort was made to do so through correspondence. A personal examination of the area was, however, not made by the entomologist, and a clipping from the Hartford Courant of June 6 reports them present.

In this year (1903), however, the first record of the periodical Cicada from Rhode Island was obtained, no brood having previously been reported from this State. The late James M. Southwick, curator of the Museum of Natural History, Roger Williams Park, reported under date of May 23d that a living specimen of the Cicada was brought to him that day taken near the southwest corner of Tiogue Reservoir, about a mile north of the New London turnpike, an unsettled region with plenty of woods. The specimen was secured by Mr. C. E. Ford, of Providence, who reported that the Cicadas were making so much noise that he thought they must be frogs or toads having a late spring concert. Mr. Ford says, on the authority of his mother, that some were collected there thirty-four years before. This is a very interesting as well as unexpected record.

The distribution by States and Counties is as follows:

- Connecticut. — Hartford.

- Massachusetts. — Bristol, Franklin, Hampshire.

- Rhode Island. — Providence.681

In “The Periodical Cicada in Massachusetts” is a table giving the occurrence of the insect in New England. The portion of this table of chief interest to us is as follows:

|

Marlatt Numbers |

Year next due |

Occurrence in New England. |

|

II |

1911 |

New York and Connecticut near Massachusetts State lines. |

|

VIII |

1917 |

Dukes. |

|

X |

1919 |

Bristol, Rutland, Vt. |

|

XI |

1920 |

Bristol, Franklin, Hampshire (Mass.), Connecticut, Rhode Island. |

|

XIV |

1923 |

Barnstable, Plymouth.682 |

In the same publication is the following paragraph regarding the Bristol County swarm of Brood XI:

The Bristol County swarm was observed at Freetown, near Fall River, in 1818, 1835, 1852 and 1869. “In 1818 they were very numerous, in 1852 still less, and in 1869 were quite scattering as compared with 1818.” Since which time there is no record of their appearance.683

From Mr. Marlatt’s opinion as expressed in his letter and from the evidence and data I have cited, I think we are justified in concluding that the swarms told of by Winthrop as occurring in 1648 belong to Brood XI of Marlatt’s classification. Swarms of this brood have appeared in areas more or less near to those designated by Winthrop in several of the years of the seventeen-year succession indicated above. Winthrop’s information was undoubtedly derived through hearsay or common report. By such means locations are not apt to be accurately defined. Moreover the disappearance of the periodical cicadas from any region may have come about, among other causes, through the cutting away of forests and the cultivation of the soil by incoming white men.

Assuming that the Winthrop swarms belong to Brood XI, we may look for the swarms which remain of that brood in 1920.

The mystery of the thirteen-year and the seventeen-year periods makes the Periodical Cicada a subject of peculiar interest. Its characteristics are so striking that, as we have seen, allusion was made to some of them by our two distinguished colonial governors in their classic narratives. There was, apparently, a break in the seventeen-year succession of the Plymouth-Barnstable swarm in the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. It is to be hoped that old records, letters, or memoranda will be found giving the years in which there were appearances of the insect during that period. But in addition it would be well that all new evidence and data of appearances, in the future as well as in the past and wheresoever occurring, be preserved and sent to the United States Department of Agriculture or to the State Agricultural Experiment Station.

Mr. John W. Farwell exhibited a volume containing several tracts684 published at London and at our Cambridge in 1662–1675 that once belonged to the Rev. Thomas Prince. On the inside of the cover is written, in the hand of Mr. Prince, “Thomas Prince. Boston. 1735,” “Thomas Prince junr his Book. 1742,” and “Sarah Prince her Book 1748.”685 On the recto of the first fly-leaf is written “Jas Murdock Jan. 1805.” On the title-page of one of the tracts appears the autograph of “Jn° Chickley.”

Mr. Farwell also presented to the Society a copy of a reproduction of a large drawing by Henry O’Connor entitled, “United States Naval Radio School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1917–1919,” depicting all the buildings occupied by the School during the War.

Mr. E. B. Delabarre read the following paper:

RECENT HISTORY OF DIGHTON ROCK

Since the publication of the earlier papers of this series,686 two minor facts have come to the writer’s attention that may now be added for completeness. Early in the nineteenth century, references to Dighton Rock began to appear in gazetteers. Worcester’s Geographical Dictionary of 1817 and Morse’s New Universal Gazetteer in its third edition of 1821 are examples. Both of them assert that no satisfactory explanation of the inscription has yet been given. The second fact demands fuller discussion. According to a writer in the Taunton Whig, in its issue of January 23, 1839, “in 1798, M. Adel, a young and learned Frenchman hunted it out, and as it was during the existence of the Gallo-phobia, his visit created a great excitement in the neighborhood. The late Dr. Baylies fell under considerable odium for harboring a Frenchman.” Judging from the contents of the other portions of the article, it seems likely that its author may have been Joseph W. Moulton, joint author with Yates of a History of the State of New York in 1824. It is probable that both the name and the date as he gives them are. slightly erroneous, and that he should have informed us that the visit was made by Citizen Adet in 1796.

Pierre Auguste Adet was French Minister to the United States from 1795 to 1797.687 He arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, from France on June 2, 1795.688 Inasmuch as he was in Philadelphia by June 13,689 it is not probable that his visit to Dighton occurred at that time. His letters from Philadelphia are almost continuous from that date until June 21 of the following year,690 after which his movements can be traced only fragmentarily. During a portion of the summer, at least, he was “travelling in several States of the Union.”691 On August 6, 1796, he was mistakenly reported as being in Boston, but his expected visit was prevented by sickness.692 By September 5, he had been in Albany and had proceeded thence to Lake George.693 On September 13 he arrived in Boston from the southward.694 He remained there for some time, being received by Governor Adams on the 14th, waited on by the selectmen on the 22nd, and given a public dinner on the 23rd.695 On October 3 he was again in Philadelphia,696 whence he sailed for France on May 6, 1797.697 His visit to Dighton, if it occurred, was probably in September of 1796. He certainly had no later opportunity. That the Gallo-phobia mentioned by our informant had not at that time attained its extreme intensity is evidenced by the public courtesies extended to him in Albany and in Boston, and by his own impressions as expressed in a letter written by him from Boston on September 24. He remarks that although the merchants are ruled by fear of England, yet “as to the people, they appear to me to be entirely devoted to us. On my journey I have received from them many courtesies and marks of affection every time that I have been recognized. I dare believe that if it were necessary they would exert all their efforts to demonstrate in a more positive manner their attachment to the [French] republic and their desire to please it.”698

With these additions, it has been possible for us, in surveying the earlier incidents connected with this persistent inciter to battles of opinion, to assemble in chronological order every incident, argument, and description that is now discoverable. With the vastly increased literature of the subject that now confronts us, such minuteness of detail is manifestly impossible, and the exact chronological order can no longer be profitably followed. Ever since Professor Rafn addressed his circular letter to the scholars of America in 1829, asking for evidences of the reputed visits of ancient Northmen to our shores, discussions of Dighton Rock have been exceedingly numerous. No single year has passed without some new printed mention of the rock, and in some years there have been many of them. Those known to the present writer within this period of ninety years now approach a total of four hundred. Their number and continuity are a clear indication of the importance attached to this monument and the deep interest that is still widely felt in its mystery. It has been its misfortune both to have been given much unmerited prominence through use of it as an alleged proof of important historical events, and likewise to have been subject to much unmerited ridicule and disrepute through realization of the follies of argument that it has incited. While endeavoring to avoid these exaggerations and to make our examination as calm and dispassionate as is the unmoved rock itself, yet it has been our constant endeavor also to accompany the search for historic truth with a realization of its human and psychological features, and with an appreciation of the entire movement with its changing incident and its varied actors, personifiers of recurring and struggling ideas, as a drama with consistent plot and strong poetic appeal. It is in this spirit, with mingled historic, psychological, scientific, and aesthetic interests, that we continue our research. Most of the material can best be handled topic by topic, instead of year by year, as heretofore; and our first task will naturally be to follow the fortunes of the Norse hypothesis from its inception down through the entire controversy that centered around it.

Rhode Island Historical Society’s Drawings, 1834

In view of the deductions which were drawn from it, apart from all question as to its reliability, no more important reproduction of the lines on Dighton Rock has ever been made than that known as the “Rhode Island Historical Society’s Drawing.” At the same time none has been subject to more of misunderstanding and misrepresentation. One current error of importance concerning it, originating in a misstatement by Rafn, is that it was made in the year 1830; and a second, that the drawing which has been frequently published under that name correctly represents what the Society’s committee saw and drew. As a matter of fact, the drawing was not in existence until four years later than the date always assigned to it; and as a matter of fact, the genuine unaltered drawing has never heretofore been reproduced.

The circumstances that led to the production of this and a companion drawing are discoverable mainly from the unpublished records of the Rhode Island Historical Society.699 The fact that Charles Christian Rafn700 was undertaking an ambitious reproduction and translation of all the Icelandic manuscripts that bear upon the Norse discovery of America, and wished to learn whether any remains of the Norsemen were discoverable anywhere on the American coast, was responsible for this new attempt to depict the characters on the rock. Rafn himself describes the earliest beginnings of the event:

When, in the course of the year 1829, after several years of preparation, we decided upon the approaching publication of this work, we felt that there were lacking various illustrations for it, to be sought in America itself. Accordingly we sought them from various learned societies of the United States of North America which presumably might provide and communicate them most readily and adequately.701

In pursuance of this purpose Rafn addressed a letter on June 15, 1829, to the Rhode Island Historical Society.702 Among other things, including mention of the runic inscription found in 1829 at latitude 73° on the west coast of Greenland, he said:

It is known, that the inhabitants in the North of Europe have long before Columbus’s time visited the countries on the coasts of North America. The greatest part of the informations concerning the same have not hitherto been published.

At a time, when the researches about the former times of America have gain’d a greater interest, durst then the undertaking of bringing for the light these informations expect the approbation of the American Antiquaries.

I have now gone through all the old manuscripts belonging to the same, and made a complete collection of the several pieces, which illustrate the knowledge, that the old Scandinavians had of America.

The collection has been made with all the accuracy which has been possible for me, and I intend now to publish this collection complete with a Latin translation. . . .

I have had the pleasure, that this my undertaking has met with a kind reception of several American learned men. I must therefore no longer consider about deferring of printing the work, which will at least take half a year.

It would rejoice me very much, If I, before the work is ready from the press, might likewise hear the thoughts of your honoured Socy about this my undertaking.

It was in consequence of the receipt of this letter that the society thus addressed sent to Rafn a number of drawings of inscribed rocks, considerable accompanying information, and two new drawings produced under its own direction. These contributions were ultimately responsible more than anything else for the now little credited belief that the Vinland and Hop of the Northmen were on the shores of Narragansett Bay. The detailed course of the events may be followed from the records of the society.

On December 19, 1829, the letter from Rafn was read to the trustees of the society, and they appointed William E. Richmond and W. R. Staples a committee to answer it (T). These men employed Dr. Thomas H. Webb, secretary of the society, to “draw up a memoir of the Writing Rocks in this vicinity, with a view to transmit the same or some parts of it to Chevalier Rafn” (R, July 19, 1830). On January 23, 1830, the trustees voted the sum of $18.62 for expenses in examining Dighton Rock, with promise of more if needed (T). In February the committee visited Dighton Rock.703 It is practically certain that on this first visit no drawing of the rock was made. At any rate, the drawings subsequently made use of by Rafn were not produced until more than four years later. However, other drawings were assembled at about this time and shortly forwarded to Rafn; and it is this fact, doubtless, that led to the later error, originating in a confusion of dates due to Rafn himself, of attributing the Rhode Island Historical Society’s drawings to the year 1830.

On September 10, 1830, the committee reported to the trustees of the society a draft of a reply to Rafn’s letter; and the trustees “resolved that the secretary cause said answer and the accompanying drawings to be copied and transmitted” (T). This was done under date of September 22 (C i. 91; R, July 19, 1831); and the letter was afterward published in full by Rafn in the Antiquitates Americanæ.704 Following is a much condensed abstract of this letter:

In the Western parts of our Country705 are numerous mounds, remains of fortifications, and articles of pottery, which could not have been produced by any of the Indian tribes; also many rocks, inscribed with unknown characters. The Indians were ignorant of the existence of these rocks. A rock, similar to these, lies in our vicinity. It is known as the Dighton Writing Rock. Its material is bluish gray fine grained grey wacke. Details of its situation and measurements are given. Its face is covered with unknown hieroglyphics. No one, who examines attentively the workmanship, will believe it to have been done by the Indians. . . . Various drawings have been made of this inscription, the first by Cotton Mather in 1712, others by James Winthrop in 1788, by Dr. Baylies and Mr. Goodwin in 1790,706 by E. A. Kendall in 1807, and one recently by Job Gardner. Copies are enclosed of the drawing by Baylies and Goodwin and the lithograph by Gardner; the others are in cited publications, and are not sent. The Committee has also examined a manuscript letter of Ezra Stiles, describing inscribed rocks at Scaticook and other places. Copious extracts are given from Stiles’s letter, and copies of some of his drawings, (not including any of Dighton Rock), are enclosed. The Committee has also heard of inscribed rocks in Rutland and in Swanzy, Massachusetts.707

Apparently nothing more was heard from Rafn for several years. Meanwhile, on April 25, 1833, the society appointed a committee on the antiquities and aboriginal history of America, consisting of Dr. Thomas H. Webb, John R. Bartlett, and Albert G. Greene.708 By the following September, the society had received a formal acknowledgment of the receipt by the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries of the letter and documents sent in 1830.709 On May 23, 1834, Rafn again made similar acknowledgment in a letter containing a long list of questions and stating his confidence that he should probably succeed in deciphering the Dighton inscription.710 A special meeting of the board of trustees was held on August 15, at which this letter was read; and it was voted “that said communication be referred to the Committee on the Antiquities and Aboriginal History of this Country, with full power to take such steps as they may deem expedient” (T). Some time between this date and the following September 27, Dighton Rock was twice visited, “the first time to make the necessary preparatory arrangements, and the second, to take a drawing of the Inscription.”711 “This Drawing,” they declared, “is confidently, offered as a true delineation of what is now to be seen on the rock, altho’ it will be found to differ much from every other copy that has come under our observation.” The committee again visited the rock, “for the third and last time on the 11th of December and the Society’s Drawing made as perfect as circumstances would admit of.”712

Meanwhile, the committee also concerned itself with formulating answers to Rafn’s numerous queries. These asked for fuller information as to the rock and its environment, the nature of the bird and the quadruped figured upon it, the occurrence of ruins or antiquities near-by,713 the occurrence of wild grapes, wild grain and ornamental wood, character of the climate, especially in winter, and the like. A draft of a reply was submitted to the trustees on October 14, 1834; and it was voted to forward it, together with the accompanying documents, and that it be signed by the president and the secretary of the society “for and in behalf of this board.”714 A few changes were subsequently made in it, and the completed document was dated November 30, though without altering the statement that the committee “reported to the Board this day” —that is, October 14.715 A second letter was also prepared and given the same date, stating that the committee had unsuccessfully attempted to find alleged inscription rocks in Swansea and Tiverton.716 Apparently there was also a third letter of the same date.717 A second report was made to the trustees on January 6, 1835;718 a fourth letter was written on January 19, and then or shortly afterwards the four letters were forwarded to Copenhagen and received there on March 30.719 It will be remembered that the drawing by Baylies and others of 1789 and that by Job Gardner of 1812 had already been forwarded in 1830. In the parcel with these new letters of 1834–1835 were included720 copies of the drawings by Winthrop 1788, E. A. Kendall 1807, Sewall 1768, and Danforth 1680;721 a book on geology, a chart and a map, and two specimens of the rock; and in addition to these the two following items, which finally prove that the true date for the society’s own drawings is 1834, not 1830:

Copy of R. I. Hist. Soc. Drawing of the Dighton Rock Inscription.722

R. I. Hist. Soc. Representation of the Rock.723

A letter from Rafn dated April 16, 1835, acknowledged the receipt of these documents and asked certain further questions about local names, the coasts of Rhode Island, and the occurrence of honey-dew;724 and on the 19th of November he made a few additional queries.725 At the annual meeting of the society on July 21 many of these matters were referred to (R). During this summer of 1835, the committee continued its activities, endeavoring unsuccessfully to obtain copies of Stiles’s drawings of the Tiverton rocks;726 seeking unsuccessfully to find alleged inscription rocks in Warwick on July 31 and on Gardner’s Point on Mattapoisett Neck in Swansea on August 5; and visiting and delineating rocks with inscriptions at Portsmouth before July 20 and on August 10, and at Tiverton on August 18 and 19.727 The results of these investigations, accompanied by drawings of the Portsmouth and Tiverton rocks, were communicated to Rafn in letters dated September 14728 and October 31.729 The second of these, as preserved in the files of the society, is a very closely written 18-page letter, discussing Indian names as well as the inscriptions, and only a small portion of it was printed in the Antiquitates Americanæ. It makes mention also of the fact that Mr. Almy, owner of the Tiverton Rocks, understood Stiles in 1780 to say that there was an inscription rock near Mt. Hope.730 On November 16 the committee made report to the trustees on its recent activities;731 and on December 11, 1835, Albert G. Greene lectured before the society on the subject of ante-Columbian discoveries. Whether or not he made mention of these inscribed rocks in that connection is doubtful, for Rafn’s conclusions on this subject were not yet published, and there is no indication that the latter had given any preliminary information as to their nature in his correspondence with the society.732

No further contributions on the subject were sent by the Rhode Island society to Denmark; but the society’s records give evidence of an active interest in these matters that continued at least until 1841. At each annual meeting during these six years the report of the board of trustees mentions a continuing correspondence with the Danish society. In 1836, moreover, the report includes a long discussion on the general subject of Inscription Rocks,733 urging further efforts toward their discovery, study and preservation, and expressing the following opinion concerning their importance:

We are confident that these memorials have been viewed by many in a wrong aspect; they have been considered as naught but insignificant scrawls, heedlessly made, and destitute of method or design. Not so are they looked upon abroad. . . . Whether, however, they are monuments erected in by-gone times by some colony or wanderers from the Eastern Hemisphere, are the peckings of idlers, (and industrious idlers must they have been), the records of the red man, or what some have hastily though not very sagely imagined, the effects of Nature’s freaks, they have proved extremely valuable to us, and will in future be viewed with an increasingly intense interest by all. . . . The Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries declares them of great importance in a historic point of view, monuments whose destruction would be an irreparable loss to science.

In 1838, the society seriously considered the possibility of purchasing the Rock, as is shown by the following record of July 19; although there is nothing further in correspondence or other records to show what steps, if any, were taken:

Resolved that the secretary be directed to address a letter to the American Antiquarian Society, and the American Historical Society, urging the necessity that measures be taken by them for the preservation of the Dighton Inscription Rock — provided the same together with a suitable portion of the adjoining land cannot be purchased by the Board of Trustees for this Society.

The last mention of Dighton Rock in the records of the society, so far as I have examined them, appears in the report of the trustees at the meeting of September 21, 1840. They speak of a letter received in April from Dr. Christopher Perry of Newport, saying that he had discovered some rocks near Newport bearing inscriptions resembling those on the rocks at Dighton and Portsmouth. “Since then the rock has been visited and examined by John R. Bartlett. The impressions were found to be very indistinct, but Mr. B. succeeded in making a drawing, which will be presented to the Society.”

Some further details concerning the making of the new drawings of 1834 can be learned from a letter written by Bartlett in 1873 to the librarian of the society:

The Society . . . appointed Dr. Webb, Albert G. Greene and myself, a Committee to visit the Dighton Rock. . . . We accordingly opened a correspondence with Captain Smith Williams, of Dighton, in relation to the rock, and upon the invitation of that gentleman, visited Dighton, and passed the night at his house. . . . Early on the following morning Captain Williams sent a man to the rock . . . with brooms and brushes to clear it of weeds and moss. . . . We crossed in a boat. . . . When it was completely exposed to view, Dr. Webb and Judge Greene traced with chalk every indentation or line that could be made out, while I, standing further off, made a drawing of them. . . . As I progressed with my drawing, my companions compared every line with the corresponding one on the rock, to be sure that every figure was correctly copied, and nothing omitted. We were several hours thus employed and it was not until the tide had begun to flow and cover the rock that we desisted from our labors. . . .

Dr. Webb and I afterwards traced several miles of the shores of Rhode Island in search for inscribed and sculptured rocks. We discovered several of which I took copies, and which Dr. Webb afterwards transmitted to Copenhagen. There was nothing remarkable in these sculptures, which were, doubtless, nothing but the scratches of some idle Indians, without any meaning.734

Further indications of the great care with which the Dighton Rock Drawing was made are given by Dr. Webb. In his letter of 1834 he says:

Our Committee have taken particular pains to represent on the Society’s Drawing all that could be satisfactorily made out upon the lower part of the rock. This was formerly, no doubt, well covered by the Inscription; but if ever as deeply engraven as the upper portion, it has become, through the lapse of time, and the war of the elements, so far obliterated, that it is utterly impossible to follow the lines. We have copied, with continuous lines, all that is still to be clearly ascertained, much of which, it will be seen, varies from every other representation, not even excepting Dr. Baylies’; we have also shewn, by broken or interrupted lines, certain portions which we feel considerably confident about, although the unaided eye would not have enabled us to copy them; but there is much, very much, that is beyond our power to delineate with the least degree of accuracy; all such, we have, of course, left unrepresented.735

In another letter written in 1854, Webb speaks of the importance of viewing the inscription at different times of day and by different lights, and continues:

In the drawing transmitted to the Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries portions are represented in different ways; three modes are resorted to,736 according to the distinctness or faintness of the original; and much was so extremely indistinct, that we deemed it advisable to leave the spaces, thus conditioned, blank. What is figured was carefully examined by four individuals, each inspecting for himself, and subsequently conferring with the others; and nothing was copied unless all agreed in relation to it.737

The accusation has sometimes been made738 that the committee who made the drawing knew of the theory that Rafn was seeking to prove, and complaisantly allowed their imaginations to discover confirmatory letters and figures on the rock. As Webb put it, in the letter last quoted: “Another boldly and shamelessly asserted, that knowing what the Danish society wished to find there, or to make out, we, the suppliant tools, formed and fashioned characters accordingly.” Such a charge is clearly baseless. It is practically certain, as already stated, that the committee knew nothing concerning Rafn’s conclusions before these were published; the above descriptions give evidence of the extreme care with which the drawing was made; and comparison of the genuine and original drawing with Rafn’s reproduction is sufficient to show that all of the imaginative features on which the Norse theory was based are due to Rafn, and not to the committee. The same considerations afford a sufficient answer to even more extravagant accusations against the Rhode Island committee. There is no need to take them seriously. But mention of them adds a bit of humor in the midst of our long discussion, and serves to illustrate the infinite variety of opinion and controversy that centers about this rock. Laing put his accusation in a facetious form in speaking of “the ridiculous discovery of the Runic inscription” and of its companion in crime, the Newport mill. “Don Quixote himself could not have resisted such evidence of its having been a wind-mill. But those sly rogues of Americans dearly love a quiet hoax. It must be allowed that these Rhode Island wags have pulled off their joke with admirable dexterity.” But Melville was apparently serious in claiming “this inscription has been copied by some designing wretch, and forwarded to . . . Copenhagen, undoubtedly for deception;”739 and so too was an anonymous writer of 1881 who, in a paper about as full-crammed with errors in statement as it could hold, remarked that “some person, in order to practice deception, forwarded an altered copy of the inscription.”740

On the other hand, excessive praise has sometimes been accorded to this drawing, as the best and most reliable ever produced. There is no such thing as a “best” drawing or photograph, except such as depict the face of the rock in its natural condition, without any interpretative preliminary tracing of its supposed lines by means of chalk or other substances designed to render them easier to reproduce.741 In this case, the lines were chalked.

plate xxxiii

BARTLETT’S VIEW OR SKETCH, 1834

from a photograph of the original in the royal library. copenhagen

plate xxxiii

RAFN’S REPRODUCTION OF BARTLETT’S VIEW OR SKETCH, 1837

from antiquitates americanae, 1837, tab, x. engraved for the colonial society of massachusetts

We have seen that there were two drawings of Dighton Rock produced by the committee of the Rhode Island Historical Society in 1834 and forwarded to Rafn. To distinguish them, we shall hereafter make use of Rafn’s distinctive terms, referring to the one usually known as the “Rhode Island Historical Society’s 1830” as the “Drawing” of 1834; and to the other, representing the rock in its surroundings, as Bartlett’s “View” or “Sketch” of the Rock.

The Drawing was made sometime between August 15 and September 27. Examination of the tide data for that year enables us to approximate even more nearly to the exact date. There could not possibly have been a sufficiently long exposure of the face of the rock to permit of the several hours of work over it that Bartlett describes, unless at an exceptionally low tide. Only one such occurred between the dates mentioned. There were three spring tides within this period, following the full moon of August 19, the new moon of September 3, and the full of September 17. On the first and third of these occasions the water at low tide — unless attended by unforeseeable circumstances which would not have influenced the choice of the day — probably did not fall below mean low water. But at the new moon period, with perigee occurring on the following day, low water at Newport probably fell .6 foot below mean on September 3, again .6 on September 4, and .7 on September 5; and there must have been an even more extensive fall in the Taunton River.742 We may then conclude with practical certainty that we are justified in fixing the date of the Drawing as on or about September 4, 1834, with the possibility that some revision of it was made on the occasion of the final visit to the rock on December 11.

The View also was doubtless sketched on one or both of these dates; but was probably completed at home, for some of the features included in it are far from being correct representations of the actual scene.743 The hill shown behind the rock does not exist in that place, though there is a very slight rise there, and a wooded hill a considerable distance further back. The peculiarly shaped boulder shown on its summit is not now, at least, either on top of the slight rise of ground near the rock or on the summit of the hill, although there is a delicately poised boulder, differently shaped, on the slope of the hill and entirely invisible from the shore. The view, then, introduces fanciful details and hence was probably not executed on the spot. Its presentation of the inscription on the face of the rock is similar to that of the Drawing, but is much more sketchy and was evidently not designed to be exact.

Inasmuch as there developed in the course or my investigations reasons for believing that what purport to be reproductions of these two drawings in the Antiquitates Americanæ could not be relied upon to assure us what the original drawings were like, I made search for the latter. Unfortunately no copies of them have been preserved by the Rhode Island Historical Society. On writing to Denmark, however, I discovered that the original drawings themselves are preserved in the Royal Library at Copenhagen, and thus I was enabled to secure photographic copies of them, which are reproduced in Plates XXXIII and XXXIV.744

Rafn’s Reproductions of these and other Drawings, 1837

In his Antiquitates Americanæ, which appeared at last in 1837, Rafn presented nine drawings of the Dighton Rock inscription, besides the View of the rock, and six drawings of the Tiverton and Portsmouth inscriptions. Most of these were reproduced from the drawings sent to him by the Rhode Island Historical Society. Those by Mather and by Greenwood, which Webb mentioned but did not copy for him, he must have taken from Archaeologia; and the Danforth and Sewall he may have derived from either source. The two earlier papers of this series have shown in one plate the nine drawings as copied by Mallery from Antiquitates Americanæ; and in succeeding plates, more accurate reproductions of the originals of them all except the two of 1834.

In presenting the two new drawings of the Rhode Island Historical Society, Rafn was not content merely with accurately reproducing them as they were sent to him. Consequently we exhibit his reproductions side by side with their originals in Plates XXXIII and XXXIV. In the View,745 it will be seen that he has greatly embellished the landscape, and that also he has introduced a great deal more of detail in the inscription. The added details have clearly been transferred from the other Drawing. The reproduction of the Drawing746 is very faithful to the original with the minor exception that the outline of the rock has been copied from the View instead of from the original drawing, and with the further exceedingly important exception that in certain parts of the inscription Rafn added a number of conjectural lines of the most essential importance for the interpretation of the inscription that he advocated. These inserted lines are all, with one exception, in the central portion of the inscription, and are as follows: the entire character, resembling a Greek Gamma, that precedes the three X’s; the very short lower portion of the right-hand line of the character M in the same line; in the line below, following the diamond shape, the lower half of the upright line of the R, all of the F except the upper half of its upright line, the entire I, the first upright of the misshapen N, and the two horizontal lines of the X; and finally, at the extreme left of the drawing, all of the P-like character except its dotted outlines, which by themselves alone do not resemble a P. Rafn believed that he was justified in supplying these conjectural restorations, through a comparison of the Rhode Island Historical Society’s drawing with earlier ones, especially those of Kendall and of Baylies. In fact, all of his inserted lines are present in one or more of the earlier drawings, with the exception of those of the F. Here, where both of the Rhode Island drawings have allowed him sufficient space to insert the two characters, FI, one or the other of them must be taken as an absolutely unsupported conjecture on his part; and a careful study of the rock itself, or of the Hathaway photograph747 of it, shows that there is absolutely no trace of more than one character in that position, and actually no room for two of them. By means of these amendments to the drawing, Rafn believed that he could read the following numerals and words as part of the inscription: CXXXI, NAM, THORFINS. For his purpose, the Gamma was interpreted as a C; and the P, either the one alluded to above or an assumed one immediately before the O, as the Icelandic Þ, equivalent of TH.

On the drawing as he presented it, Rafn attempted to distinguish his own additions by drawing them with shaded lines. Unfortunately, the shadings are not very distinct, and are easily overlooked.748 Of the fifteen later reproductions of this drawing known to me, six present it without any shading or other marks of distinction whatever, and few of the others copy the shaded portions in exactly the same positions as on the original.749 Moreover, although it may be inferred from his discussion of these portions of the drawing in his text,750 Rafn nowhere explicitly says that the shaded lines are additions by himself, but misleadingly calls the whole “The Rhode Island Historical Society’s” drawing. As to the View, there is nothing whatever in text or in distinguishing marks on the drawing that could lead one to infer that he had greatly amplified and embellished what was sent to him, hence he wrongly attributes it to J. R. Bartlett as its delineator. As a consequence, only the most critical readers of his text have clearly realized how much of the depicted inscription was due to the actual observers of the rock, and how much was purely conjectural; and this fact has led to much misconception as to the strength of the argument for the Norse theory of the origin and meaning of the inscription. Hereafter, no one should refer to either of the two drawings in the Antiquitates Americanæ; as those of the Rhode Island Historical Society. They should evidently be known as Rafn’s conjectural drawings, based on a comparison of the Rhode Island drawings with those of earlier date.

It is a curious fact that none of the originators of the drawings, so far as I have knowledge of their published writings and unpublished letters, ever disputed the correctness of the date that Rafn assigned to them, or the justice of calling them, exactly as they were published, the Rhode Island Historical Society’s drawings. Webb, we have seen, even came to believe that the shaded lines as well as the others had been drawn by his committee. It has required a careful study of Rafn’s text, a comparison of the statements of nearly all the later expositors of his theory, and finally an examination of the original records of the Rhode Island Historical Society and the securing from Denmark of copies of the original drawings, to make possible a presentation of the actual facts.

The results of Rafn’s studies were published in 1837 in an impressive volume entitled Antiquitates Americanæ;. A month before it appeared, however, a brief hint concerning his conclusions about Dighton Rock had already been given. The periodical called Dansk Kunstblad in its issue of March 17 reproduced Kendall’s drawing of the rock, and remarked: “A rock found in Massachusetts, which is covered with numerous hieroglyphics and sundry characters of Runic appearance, will, if correctly delineated, furnish to our antiquaries unlooked for elucidations of the olden time of America, and of its indisputable connexion with the old world in times that are long since passed away.”751

Antiquitates Americanæ, 1837

Whatever may be said of the success of the attempt to connect Dighton Rock with the visits of the Northmen to America, and through it or otherwise to identify localities connected with their discoveries, the service rendered by the publication of the Antiquitates Americanæ; was a memorable one. The book is a quarto volume of 526 pages, illustrated by facsimiles of some of the ancient manuscripts, by maps and charts, and by six engravings of Greenland and American monuments. The body of the work contains an Introduction written in Danish and Latin; a Conspectus of the eighteen manuscripts presented; a twelve page essay written in English entitled “America Discovered by the Scandanavians in the Tenth Century. An Abstract of the Historical Evidence Contained in this Work;” the original text of each of the Icelandic manuscripts with a Danish translation in parallel columns and a Latin translation subjoined; lengthy discussions in Latin of monuments found in Greenland and America; and finally, geographical annotations in Latin, and indexes.

In order to appreciate satisfactorily the setting into which the theory of Dighton Rock was fitted, it is necessary to review briefly the story given in the Historical Abstract. Eric the Red settled in Greenland in the spring of 986. Later in the same year, Biarne Heriulfson, attempting to join Eric’s colony, was driven out of his course and saw strange lands of three typically different characters, but did not go on shore. In 1000, Leif, son of Eric, set forth to discover Biarne’s new lands. The first that he found he called Helluland (identified by Rafn with Newfoundland), the second, Markland (Nova Scotia), and the third Vinland, because of the wild grapes found there (vicinity of Cape Cod and Nantucket). Here he erected large houses, afterwards called Leifsbooths (in Mount Hope Bay), and wintered. Thorwald, Leif’s brother, sailed in 1002, and passed two winters at Leifsbooths. He explored the country to the south, and gave the name Kialarnes to a prominent headland (Cape Cod). He was killed in a contest with Skrellings, and was buried at Krossanes (Gurnet Point). His companions wintered once more at Leifsbooths. In 1005, Thorstein, another son of Eric, made an unsuccessful voyage. Thorfinn Karlsefne, a wealthy and powerful man of illustrious lineage, went from Iceland to Greenland in 1006, accompanied by Snorre Thorbrandson, Biarne Grimolfson, and Thorhall Gamlason. Thorfinn married Gudrida, widow of Thorstein. In the spring of 1007 he set sail in three ships with his wife and companions, together also with Thorward and his wife Freydisa, daughter of Eric, and another man named Thorhall. They had with them 160 men and much livestock, intending to establish a colony. They found all the places already named, and gave names also to Furdustrandir (Wonder strands; the long sandy stretches of Cape Cod), Straumey (Stream Isle; Martha’s Vineyard), and Straumfiördr (Streamfirth; Buzzards Bay). At the latter place they landed and wintered. Thorhall with eight men left them. The others sailed southwards and arrived at Hop (Mount Hope Bay), where they found wild wheat and vines. They saw natives, erected dwelling houses a little above the bay, and wintered there. No snow fell. In the spring of 1008 (1009?) they traded with the natives, who were frightened away by the loud bellowing of a bull. About this time Gudrida gave birth to a son, who was named Snorre. Early next winter they were attacked by the Skrellings, but repulsed them after a severe conflict. In consequence of the hostility of the natives, they left Hop, and after some further exploration they spent the third (fourth?) winter at Streamfirth, and returned in 1011 to Greenland.752 In 1012–13 another expedition to Leifsbooths was made under the leadership of Freydisa. Later voyages also occurred, ending with one to Markland in 1347.

The Inscription Interpreted by Magnusen and Rafn

Rafn supported his identifications of localities by arguments drawn from geographical and nautical descriptions, by statements concerning climate and soil, produce and natural history, and by an observation seeming to determine the length of day and hence the latitude. But the most conclusive evidence that the Hop of the Northmen was situated at the head of Narragansett Bay, he believed, is furnished by the inscription on Dighton Rock. Apparently before he had received the new drawing of 1834, Rafn submitted some or all of the earlier drawings to Finn Magnusen753 for his opinion of them.Magnusen’s report, based wholly on the Baylies drawing of 1789, was as follows:

I am glad to say that I support unhesitatingly your opinion as to the inscription and figures on the Assonet rock. I believe there is no doubt that they are Icelandic and due to Thorfinn Karlsefne. The Icelandic letter Þ, near the prow of a ship, at the spectator’s left, shows this at first glance, as do also the principal configurations cut in the rock. Several other considerations support this belief. I. The numeral characters CXXXI exactly correspond to the number of Thorium’s men; for these were CXL, of whom nine under Thorhall left him at Straumfirth. With the rest he went to Hop. Under the numeral characters appears the combination  , consisting of two letters, a Latinogothic N and a runic M,754 standing for norraenir (north) and menn or medr (men). Between them is a ship divested of masts, sails and ropes, indicating that these men came to this land in the ship but later left it after removing its masts, sails and ropes, and erected fixed habitations on the land occupied by them. The whole phrase means: CXXXI North-European seamen.

, consisting of two letters, a Latinogothic N and a runic M,754 standing for norraenir (north) and menn or medr (men). Between them is a ship divested of masts, sails and ropes, indicating that these men came to this land in the ship but later left it after removing its masts, sails and ropes, and erected fixed habitations on the land occupied by them. The whole phrase means: CXXXI North-European seamen.

II. Following the numerals CXXXI is a Latino-gothic character resembling an M, the right-hand half of which has a crossline making it, taken by itself, an A. This is a monogrammatic combination standing for NAM, equivalent to land-nam. Underneath it is a diamond shaped O followed by an R. This OR is an ancient Scandinavian form for modern Icelandic and Danish vor, in English our. Nam or signifies “territory occupied by us,” or “our colonies.” — III. In the highest part of the configuration, above the portions just discussed, is a rather artificial figure755 representing in our opinion a great shield provided with a singular foot resembling a fish-tail. This shield, together with the adjacent inverted helmet, I accept as symbols of the peaceful occupation of this land. — IV. This occupation, or the cultivation of the land or development of the colony, is further indicated by a very crude figure cut in the rock underneath the n of norraenir, if this, as we conjecture, represents a heifer lying down or at rest. At the time of the first occupation of Iceland, the ground covered by a heifer in its wanderings during a summer’s day customarily determined the extent of the land to be occupied. — V. I believe that the configuration as a whole presents to the spectator this scene: the famous ship of Thorfinn Karlsefne as it first set out for Vinland and came to this shore, with a wind-vane756 attached to the mast. His wife Gudrida, seated on the shore, holds in her hand the key of the conjugal dwelling, at that time, as is evident, long previously constructed.757 Beside her stands their three year old son, Snorro, born in America. Thorfinn’s CXXXI companions were then occupying Vinland, and had declared it to be their own possession, thus occupied. One of their ships in which they had come, is represented fixed to the shore, for this reason despoiled of its sails.758 A cock759 announces by his crowing domestic peace, as do also the shield at rest and the inverted helmet. Then suddenly approaching war is indicated. Thorfinn,760 leader of the colonists, is seated, enjoying rest; but he seizes his shield761 and endeavors to protect himself against the approaching Skrellings,762 who violently assail the Scandinavians, armed with clubs or branches, with bow and arrows, and furthermore with a military machine, unknown to us, which in Thorfinn’s history is called a ballista, from which are thrown, besides missiles and large rocks with ropes attached, as is seen, also a huge ball, which fact is testified to in express words in the same history.763 — VI. Certain other features of the inscription, ropes and runic enigmas, must be left unexplained.764

Rafn devotes 42 pages of the Antiquitates Americanæ;765 to his own discussion of Dighton Rock. First he reproduces the letters which he had received from the Rhode Island Historical Society, then quotes the accounts of the rock that had been published by Lort, by Warden, and by Vallancey.766 Since his time these sources have been accepted as the basis of nearly all accounts of the earlier history of investigation of this subject; but how inadequate this account is both in accuracy and in completeness has been shown constantly in the course of our own investigation. Rafn then announces: “We are of the opinion that the inscription is due to the Icelanders. Finn Magnusen, an expert in Runic inscriptions, whose opinion we consulted, supports us.”767 Magnusen’s interpretation is presented, the nine copies of the inscription known to Rafn are enumerated, and finally he reviews the opinions of Magnusen and adds corrections and amplifications of his own. Concerning the numeral characters CXXXI in division I, it will be noticed that Magnusen left them without stating their equivalence in Arabic numerals. Rafn expresses the belief that the C stands for the Icelandic “great hundred,” which is ten dozen instead of ten tens. Hence the whole signifies not 131 but 151, the true number of Thorfinn’s men after Thorhall’s nine had left. The Gothic N and Runic M with a dismasted ship between them are to be regarded as less certain, since they are to be found on the Baylies drawing only. Nevertheless, Magnusen’s explanation of them fits in so well with the numerals, that their real existence at least formerly is of the highest degree of probability. Under II the NAM is accepted. But instead of OR Rafn finds in the Rhode Island drawing, supported in part by Kendall, as we have already seen, the fuller ORFINS.

plate xxxiv

RHODE ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S DRAWING, 1834

from a photograph of the original in the royal library, copenhagen

plate xxxiv

RAFN’S SO-CALLED “RHODE ISLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S 1830” DRAWING, 1837

from antiquitates americanae, 1837, tab. xii, plate ix. Engraved for the colonial society of massachusetts

In front of these six letters Greenwood’s picture places a curved line, which is seen also, among others, even in Mather’s earlier drawing. We are not very rash in suspecting this stroke to belong to the letter Þ with its first upright line now exceedingly worn or even wholly invisible. If therefore we accept this letter as having been expressed in this place, or even recognize as a Þ that letter which, though not a little distant768 from the succeeding letters, is yet visible in the Rhode Island Society’s drawing and is plainly and accurately delineated in the Baylies drawing at the first of the representations of a ship, then there results, according to the greatest probabilities, this reading for the two lines of the inscription, disregarding the numeral characters:

NAM ÞORFINS.

The whole inscription, therefore, reads: “Thorfinn and his 151 companions took possession of this land.”

In III, Rafn accepts the interpretation of the figure as a shield, and describes the ancient shields, of which this is a true representation. The figure of a heifer in IV, given in the Baylies and in some part also in the Rhode Island drawing, is very different in Winthrop. Its interpretation is subject to doubt, but yet sufficiently probable. Rafn continues:

V. The principal scenes of this representation correspond so perfectly with the accounts in the old Icelandic writings that this historical interpretation of their meaning is hardly to be regarded as rash or erroneous. The arrival of the Scandinavians in Vinland, their occupation of the land and even their encounter with the Skrellings, are here easily recognized. The figure of a man standing in the middle is given in the Baylies but is lacking in the more recent drawings, and hence is somewhat doubtful. Unless this figure was once there and has since been destroyed by erosion, then the human figure next to the ship769 ought to represent the leader of the expedition. At his side the best drawings show the figure of a child, which probably indicates Snorre. . . . In my opinion this assumption is proven by the fact that at his right side the Rhode Island drawing places the Runic letter S,770 initial of his name. The animal, placed under the upright shield in most drawings, is represented as having horns. We take it to represent the bull which is mentioned in Thorfinn’s history.

The figures at the right, Rafn thinks, are very probably Eskimos with their weapons: stretched bow, ball flying through the air with rope attached, arrow-head, and finally a projected stone dashed against the upper margin of the shield. — VI. The rest is too doubtful for correct interpretation, though, as Magnusen says, there are resemblances to runic letters. — VII. Other examples of inscriptions are cited in support of the theory here advocated.

Following this account of the Assonet inscription is given a description of the inscriptions at Portsmouth and Tiverton in Rhode Island.771 These, according to Rafn, confirm his opinion as to Dighton Rock. We can see in them certain runic letters of undoubtedly Scandinavian origin, eight of which are specifically mentioned. Finn Magnusen agrees that runic letters occur in the drawings, some of which have a genuine significance. He finds, for example, the runes standing for the letters L and T, and says of them: “We assume that Leif and Tyrker wished to indicate thus their names by their initial letters.” Other composite characters occur that are to be taken as monograms. He thus discovers the names An and Aki, and assumes that men of these names accompanied Thorfinn.

No shore to which the Northmen came

But kept some token of their fame;

On the rough surface of a rock,

Unmoved by time or tempest’s shock,

In Runic letters, Thorwald drew

A record of his gallant crew;

And these rude letters still are shown

Deep chiseled in the flinty stone.772

Inadequacy of these Views

Although not including quite all the detail given it by Rafn, yet the foregoing presents fairly the evidence offered in the Antiquitates Americanæ; for the famous Norse theory of the inscription on Dighton Rock. Reserving for a moment the question as to the presence there of the name Thorfinn, it is clearly evident that all the rest of the alleged translation is pure romancing, on an exact par with the detailed readings of Gebelin, of Hill, and of Dammartin. The reader who has followed the changing phases of depiction and interpretation of the inscription thus far must realize that it is easy to imagine as present on the rock almost any desired letter of the alphabet, especially of crude or early forms; and that, starting with almost any favored story, he can discover for it, if he looks for them eagerly enough, illustrative images to fit its various features, and initial letters or even entire words or names. Later examples will give even stronger confirmation of this fact.

Aside from an undoubted fascination in the thought of the bold Norsemen sailing without compass the stormy seas and discovering and colonizing these shores so long a time before Columbus, the one thing that has led to so confident, widespread and prolonged acceptance of Rafn’s views concerning Dighton Rock has probably been the apparently clear presence of the name of Thorfinn on the rock. It is undeniably there, plainly visible to everyone, in Rafn’s seemingly scholarly compilation of the different extant drawings, published in an impressive volume issued by a highly reputable learned society. It is hardly a matter for wonder that so many persons have seen no reason to doubt the reliability of the depiction. But if this one word can be shown to be doubtful, or indubitably not there, then the whole fabric of Rafn’s and Magnusen’s ingenious readings falls with it and their translation of the rock’s inscription becomes as much a fairy tale as are its earlier and later rivals.

Is there, then, any possibility that the name Thorfinn was cut upon Dighton Rock? We can answer with entire confidence that there is not. A number of distinct arguments may be cited, each one of them wholly convincing. (1) Examination of all of the discoverable drawings and photographs shows that not one of them contains the name. To repeat a statement made in an earlier paper,773 of thirty attempts known to me to depict this portion of the inscription, about 85 per cent exhibit the diamond shape that Rafn called an O; only 2 show an R, 3 others something similar, all the rest nothing like it; in the position where Rafn placed FI, no one has anything like an F, 14 have an I, 10 others some other character, and 6 have nothing; next beyond, Kendall presents a misshapen N, and all the rest some shape that has no resemblance to it; in the final place, all but one give an X. Opinion is almost unanimous that there is nothing there that at all resembles ThORFINS. (2) If the name were actually there, or ever had been, later careful examinations of the rock, often by persons eager to verify Rafn’s views, should have shown some confirmation of its presence. Of reproductions since 1837, there are eighteen. All of them have the diamond shape, usually with a vertical attachment below; not one has R, and only one anything resembling it; not one gives two characters in the FI position, and only about half of them draw the single character there as an I; not one finds anything like an N, unless we except the single case where a complex character occurs within which an N could be separated out; all give X, and without horizontal lines either above or below except in two cases. Thus all attempts to confirm Rafn’s guess have served only to prove it incorrect. (3) Anyone may now prove the matter for himself as completely as if he were to visit the rock and examine it under favorable conditions of light and tide. Study of the Hathaway photograph774 is for this purpose superior to direct examination of the rock, for it shows the smallest details of texture of the surface with almost ideal clearness, and can be examined at leisure and in comfort — conditions that the rock itself rarely offers. The result of such study must be the conviction that between the reputed R and N there is not room for two characters unless the R is unduly narrowed, and no trace of more than one; and that although the actual lines are often doubtful yet the conjectural additions made by Rafn are wholly imaginary, corresponding to no actual markings on the rock.775

At a later date Rafn added to his “proofs” of the location of Vinland in the region of Narragansett Bay two other objects which played a prominent part in subsequent discussions. One of these was the Stone Tower or Old Mill at Newport.776 There are very few people now who doubt that this structure is identical with that mentioned by Governor Benedict Arnold in his will of 1677 as “my Stone built Wind Mill,” and that it was erected not more than two years earlier on the model of one in England with which Arnold must have been familiar in his boyhood. The facts leading to this conclusion were first announced by Melville and Brooks, made widely known by Palfrey, and corroborated by Mason’s expert examination of the architectural evidence.777 The other apparent relic of the Northmen was the famous “Skeleton in armor” celebrated by Longfellow, discovered in Fall River in 1831.778 The only foundation for its shortlived acceptance as evidence in favor of Rafn’s views lay in the fact that there were found with it a brass breast-plate and a belt made of brass tubes. The argument lost its force when other skeletons similarly equipped were found,779 when it became known that the Indians were abundantly provided with similar metallic articles when the white men first came into contact with them,780 and when it was realized that the brass of this particular armor might well have been secured by Indians from early traders or colonists.781

In justice to the men most prominently responsible for introducing Dighton Rock and these two companions into the story of Norse discoveries, a word should be said as to their later expression of views. Already in 1838, Rafn referred to the evidence given in Antiquitates Americanæ; merely as “hints,” and said that the matter would continue to form a subject for accurate investigation. In a letter of January 4, 1848, to David Melville of Newport he said that these monuments “unquestionably merit the attention of the investigator, but we must be cautious in regard to the inferences to be drawn from them.” Yet his letters to Niels Arnzen between 1859 and 1861, in which he approves of a project to remove Dighton Rock to Denmark, show that he still regards it as of “high and pressing importance.” The Royal Society of Northern Antiquaries, however, eventually abandoned all belief in the value of the rock as evidence, as is shown by a letter of February 22, 1877, addressed to Arnzen, signed by four officials in behalf of the government of the society, and by a letter of November 1, 1878, from the Society’s vice-president, J. J. A. Worsaae, to Charles Rau. The official letter to Arnzen says: “The Society must confess that the inscribed figures on the Rock have, according to the later investigations, no connection with the Northmen’s journeys of discovery or sojourn in America, but rather that it is the work of the original races of Indians.” Bartlett, in 1846, expressed his belief that no alphabetic characters had been satisfactorily identified on Dighton Rock; and many years later he wrote: “I never believed that it was the work of the Northmen or of any other foreign visitors. My impression was, and is still, that it was the work of our own Indians. . . . Nor do I concur in the belief that it was intended as a record of any kind.”782 Webb apparently clung persistently to the belief that the inscription was Norse, yet conceded that it might be otherwise: “If its anti-Runic character should be satisfactorily shown,” and “allowing it to be an Indian Monument, it should be none the less highly prized and carefully preserved.”783

It is now generally conceded by everyone whose opinion is of value that no material remains of the Norse visits to America have ever been discovered. The nearest indubitable one is that found in 1824 at Kingiktorsoak on the east shore of Baffin Bay. Perhaps we ought to except the so-called Kensington Stone in Minnesota, which has an inscription in characters which are undoubtedly runic, but whose authenticity is still in question.784 It may be that this will turn out to be, so far as its connection with Northmen is concerned, in the same class as the hoax of Potomac, the fraudulent or at least dubious stone of Grave Creek, and the natural markings or Indian picture-writings of Monhegan, Yarmouth, and other places whose “inscribed stones” have been attributed from time to time to the discoverers of Vinland.785 Other remains of old times besides inscriptions, the best known of which are those of Horsford’s Norumbega near Boston, likewise lack proof of any association with these explorers from Iceland and Greenland. The whole matter is well summed up by Babcock:

So far as investigation has gone, there is not a single known record or relic of Wineland, Markland, Helluland, or any Norse or Icelandic voyage of discovery, extant at this time on American soil, which may be relied on with any confidence. There are inscriptions, but apparently Indians made them all except the freakish work of white men in our own time; there are games, traditional stories, musical compositions, weapons, utensils, remnants of rude architecture, and residua of past engineering work, but no link necessarily connects them with the period of Icelandic exploration or with the Norse race. One and all they may perfectly well be of some other origin — Indian, Basque, Breton, Norman, Dutch, Portuguese, French, Spanish, or English. Too many natives were on the ground, and too many different European peoples, who were not Scandinavians, came here between 1497 and 1620 for us to accept anything as belonging to or left by a Norse Wineland, without unimpeachable proof.

Present Status of Question as to Location of Vinland

But the absence of still existent monuments does not in the least degree invalidate the main story of the sagas. John Fiske rightly said: “The only discredit which has been thrown upon the story of the Vinland voyages, in the eyes either of scholars or of the general public has arisen from the eager credulity with which ingenious antiquarians have now and then tried to prove more than facts will warrant.” We can cheerfully reject this theory about the rock whose complicated history, more remarkable than the rock itself, we are studying. But it is impossible to have searched minutely for all discoverable discussions of the rock without having read much about the voyages to Vinland and Hop, and wondering where after all these places may have been. Our researches, centered on an entirely different though interweaving question, have not rendered us competent to utter an expert opinion in this matter; but they have made it possible to say a brief word concerning the opinions expressed by others. For fifty years after the appearance of Antiquitates Americanæ, opinion was almost equally divided between the followers and the opponents of Rafn’s views. Out of more than a hundred persons who wrote on the subject, and whom I have consulted in order to obtain a well-founded idea as to how the Dighton Rock story was greeted, about 46 per cent were confident that he had solved the problem correctly, while 11 per cent more accepted his localities without sharing his deductions concerning Dighton Rock. Among them all, however, there was hardly another one who supported the opinion so long defended by Bancroft, that the sagas gave no assurance that the Northmen ever discovered the continent of America. If we accept the almost unquestioned belief that they did land somewhere on American shores, the most helpful indications as to how far south they penetrated are furnished by vague sailing directions, a crude observation as to the length of day, and statements concerning useful plants that they found. As to the latter, so long as it was believed that their vinber were grapes, their self-sown hveiti Indian corn, and their mosur wood, maple or the like, the probabilities seemed to most critical students strongly in favor of New England. But in 1887 there appeared two books which ultimately were strongly influential in altering the reading of the evidence. Gustav Storm786 showed that neither the distribution of the grape, nor the identification of the other plants, nor calculations as to length of day, nor any other observations made in the sagas, compel a belief that Vinland lay farther south than about 49° north latitude, and that it certainly could not be farther north. Nova Scotia seemed to him its most probable location. In the same year Garrick Mallery, by publication of his Pictographs of the North American Indians, greatly extended an already considerable knowledge of the extent to which the Indians, throughout widely separated areas, had made pictures and markings upon rocks, in many cases not unsimilar to the “hieroglyphs” on Dighton Rock, and thus furnished stronger foundation than had before existed for the contention that the latter need be ascribed to no other source. Doubtless also Justin Winsor’s critical study of the literature of pre-Columbian explorations contributed largely to the decisive rejection of a New England Vinland. The influence of these writings, naturally, only slowly became evident in the literature of the Norse voyages. Of about thirty discussions in my list between 1887 and 1900, we find that between forty and fifty per cent are still expounding Rafn’s views. But since 1900 there has been a marked change. Of thirty references to the subject that we find recorded in our notes, only four very minor and negligible ones admit the possibility that Dighton Rock may have been a Norse record; only three others, without accepting the rock, believe that Vinland lay so far south. The remainder, nearly eighty per cent of all, either place Vinland farther north or make no attempt to determine its exact location. The most important recent contributions may well receive a moment’s notice. In 1910, Fernald contended that vinber was probably mountain cranberry (Vaccinium Vitis-Idaea), hveiti the strand wheat (Elymus arenarius), and mosur the canoe birch (Betula alba), and hence that Vinland was probably in Labrador or along the Lower St. Lawrence River.787 Babcock, examining evidence that the coast of New England has steadily subsided since glacial times and deducing the changes in coastal scenery that must have occurred since the year 1000, believes that “thus far no other Hop has been suggested which seems more plausible than Mount Hope Bay,” but that Leif’s booths were in southeastern Massachusetts. Hovgaard, once Commander in the Royal Danish Navy, comes to the conclusion that Leif reached Cape Cod, but that Thorfinn sailed no farther south than Newfoundland. Both Babcock and Hovgaard reject Fernald’s interpretation of vinber, believing that it means grapes. Yet comparatively few others among recent authorities locate Vinland or any part of it farther south than Nova Scotia. The latest book of all on the subject, whose argument cannot henceforward be overlooked, is by Dr. Andrew Fossum of Park Region Luther College in Minnesota. Instead of rejecting one or the other of the two partly conflicting sagas of the Vinland voyage, as most writers do, he contends that each of them in its main features is authentic, the one as correctly relating the adventures of the family of Eric, the other those of Thorfinn. Then, making a minute study of sailing directions and descriptions of scenery, and believing that other indications are in accord with his results, he seems to establish conclusively the fact that Leif’s Vinland and Thorfinn’s Hop were different regions, and very plausibly locates the former on the Lower St. Lawrence River and the latter somewhere on the east coast of Newfoundland.

plate xxxv

drawing of alleged roman letters (fig. e). 1847: and combination of the drawings of 1789 and 1837 by henry r. schoolcraft, 1851

from school craft’s history of the indian tribes, 1851. I, plate 36. Engraved for the colonial society of massachusetts