The Professionalization of Boston Medicine, 1760–1803*

THE professionalization1 of Boston medicine during the last half of the eighteenth century (1760–1803) went through three distinct periods. The first of these was the pre-Revolutionary or imperial phase (1760–1775) during which the drive toward greater professionalization of medicine in the New England metropolis quickened considerably but, unlike the younger, larger, and economically more dynamic New York and Philadelphia, produced no institutional results.2 This was followed by the highly disruptive Revolutionary period (1775–1780) which drastically altered both the composition and leadership of Boston’s medical community and the context in which the professionalization of Boston medicine would find institutional fulfillment. Lastly came the post-Revolutionary or national stage (1780–1803), the time in which both the institutional foundations of medical professionalization in Boston and the social context within which they would operate for the next three generations were firmly laid. This period began with an intense burst of institutional creativity (1780–1783), followed by an interval of adjustment and slackened pace (1784–1796), and then ended in another spurt of creative activity (1796–1803).

The number of trained doctors or what I term “physicians” in Boston rose from about fourteen in 1760 to around twenty-one in 1775,3 even though the city’s permanent population remained stable at between 15 and 16,000, and its economy generally was depressed.4 This fifty-percent increase in the number of physicians in the face of adversity intensified medical competition and heightened a sense of common interests and aspirations among the regularly prepared practitioners.5 It also accelerated the reduction of Boston’s apothecaries, midwives, and other medical practitioners to clearly subordinate and supportive medical roles. What is more, it made unlikely the repetition of a medical career such as that of Joseph Pynchon, who retired in 1760 as one of the city’s most eminent medical figures. Pynchon, scion of one of Springfield’s leading families, prominent political personage, and Harvard overseer, had received no formal training but simply began practicing during his free time while serving in the General Court and, despite such archaic therapy as his centipede soup, developed a large, well-to-do clientele.6

7. Dr. James Lloyd (1728–1810). From James Thacher, American Medical Biography (Boston, 1828). Courtesy Boston Medical Library.

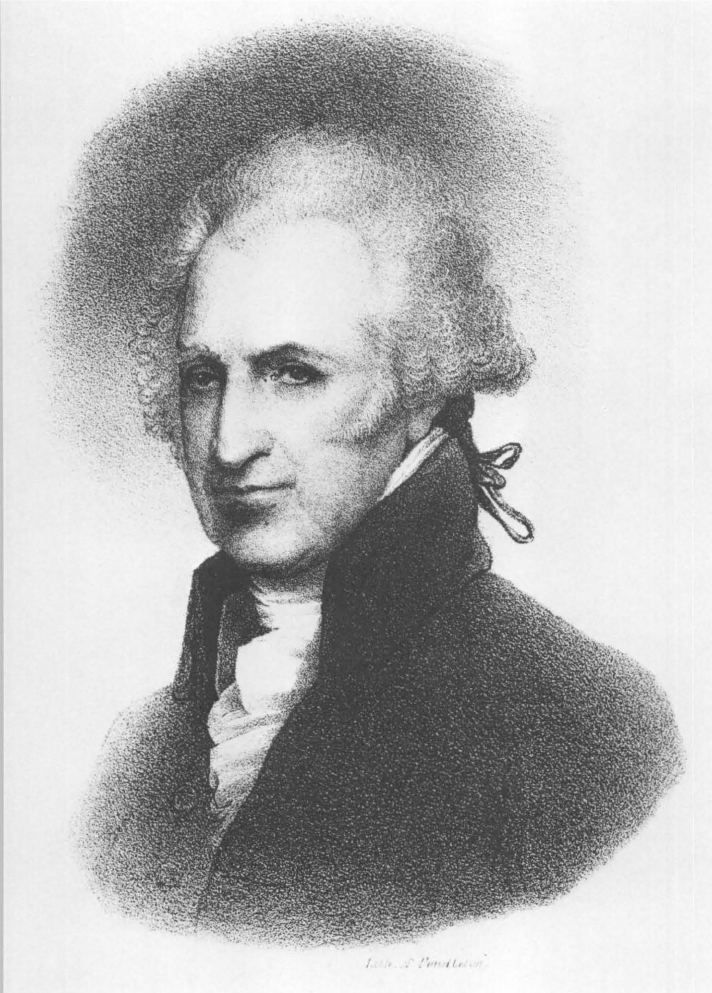

8. Dr. John Warren (1753–1815). Early nineteenth-century lithograph after the portrait by Rembrandt Peale. Courtesy Boston Medical Library.

9. Anatomical lectures attendance certificate, engraved by Paul Revere in 1780. Israel Keith (c. 1749–1819) graduated from Harvard College in 1771, a year after Warren, and was practicing law when he attended Warren’s lectures. Courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society.

10. Front page of The Boston Independent Chronicle and the Universal Advertiser for 18 September 1783, describing the organization of a Medical Institution by the Harvard Corporation and the appointment of its first three professors. Courtesy Boston Medical Library.

11. Holden Chapel, Harvard College, Cambridge. Built in 1744, it was used for medical instruction from 1783 to 1810. Courtesy Harvard Medical Archives.

12. Holden Chapel, Harvard College, Cambridge, today. Courtesy Harvard Medical Archives.

13. Massachusetts Medical College, Mason Street, Boston, seat of the Harvard Medical School from 1816, five years after it first moved to Boston, until 1847, when it moved to North Grove Street near the Massachusetts General Hospital. Courtesy Boston Medical Library.

14 (facing page). A Plan of Boston from Actual Surveys, by Osgood Carleton, a copperplate engravin of 1796. The dots locate the offices or homes of the twenty-four physicians who practiced there in 1789, according to the accompanying Appendix II. At that time they were concentrated chiefly in the center of the north-south town axis, and not in either the equally well populated North End or in the dockside commercial areas. Ten years later, when there were thirty-one physicians in Boston they were more evenly distributed through most areas of the town. Map courtesy Massachusetts Historical Society.

Between 1760 and 1775 the total number of physicians who ministered to Boston’s needs was around twenty-eight. Of these, thirteen had received formal training above the apprenticeship level. All thirteen had studied in Europe and twelve had walked the wards of one of London’s great hospitals and attended one or more of the city’s justly famous courses in anatomy, surgery, and obstetrics.7 However, only three, or possibly four, had bothered to earn a medical degree.8 This heavy emphasis on London9 and the clinical-practical aspects of medicine contributed to the relatively uniform, generally pragmatic, and basically conservative nature of Boston medical practice of this time. It probably also contributed to the limited interest that Boston physicians of this period showed in medical theory and scientific investigation as compared with those in other colonial urban centers.10 However, economic and political considerations were also important.

Unlike the other major colonial ports, Boston was noted for the homogeneity of its permanent inhabitants, and its medical community was no exception. Of the forty-seven physicians who practiced in Boston between 1760 and 1798 listed in Appendix I, all but four were New England born of English stock.11 True, there were also several French and German doctors listed in the Boston directories of 1789, 1796, and 1798, but they seem to have been on the periphery of Boston’s medical world. A majority of Boston doctors of this era could trace their ancestry back to the Puritan migration of 1630–1680. Despite important religious (Anglican-Congregational) and political (Tory-Whig, Federalist-Jeffersonian) divisions, this strong pattern of cultural similarity and localism was central to Boston medicine throughout the second half of the eighteenth century and indeed much of the nineteenth as well. However, the situation had been different during the first third of the eighteenth century, when a smaller fraternity of trained medical men in Boston was greatly influenced by such foreign-born doctors as John Cutler from Holland, Lawrence Dalhonde from France, and William Douglass from Scotland.

By 1760 Boston not only had a solid corps of physicians, but also two controversial issues to bring them together and heighten their common awareness. These issues were the establishment of inoculation hospitals and the acceleration of the integration of normal deliveries as well as extraordinary obstetrical cases into the regular practice of the physician. Of the two, the establishment of inoculation hospitals was by far the more pervasive, controversial, and immediately important. In the four decades since smallpox inoculation first had been introduced to Boston amidst savage controversy, the community had worked out a compromise procedure whereby the traditional and usually successful quarantine system would be the town’s first line of defense. When it broke down, as it did in 1730 and 1752, open inoculation would be allowed for a specified interval. The chief arguments against inoculation at this time were the very valid ones that it was beyond the means of a substantial portion of the population and that it was highly dangerous. However, by 1760, improved inoculation methods, impressive statistical evidence of its effectiveness, and the promise of great profits, as well as the appearance of permanent inoculating hospitals in other colonies, made Boston physicians extremely anxious to establish them in or near New England’s premier urban center.12

In both 1761 and 1763 well-established and well-connected members of the Boston medical fraternity attempted to set up inoculating hospitals, but they were rebuffed.13 However, the smallpox epidemic of 1764 witnessed two important breakthroughs in Boston’s attack on this dreaded killer. One was the agreement of the city’s physicians to inoculate the poor gratis, a significant manifestation of increased professional responsibility and cooperation.14 The other was the establishment for the first time in the Boston area of public inoculation hospitals at Point Shirley and Castle Island. This development also benefited greatly from the strong and apparently unanimous support of the city’s physicians.15 During this epidemic eighty-seven percent of those who contracted smallpox did so by inoculation, and for the first time a smallpox year failed to stand out in Boston’s bills of mortality.16 Still, despite continued lobbying by Boston physicians, who were greatly encouraged by their recent successes, permanent inoculation hospitals continued to be banned in and around Boston until after the outbreak of the Revolution.17 Just how powerful the lure of progress and profits was during the interval between the smallpox epidemic of 1764 and the opening of the War of Independence is illustrated by the fact that on 30 July 1774, less than ten months before Lexington and Concord and with Massachusetts in virtual rebellion, Joseph Warren, a leader of the radical Whigs, and Samuel Adams, Jr., his recent apprentice and son of Massachusetts’s leading radical, joined with Thomas Bulfinch, Jr., a political trimmer, and James Latham, a British army surgeon, to sign a twenty-one-year contract to build an inoculation hospital at Point Shirley, if the town of Chelsea would assent to it. Warren, Bulfinch, and Latham also entered into another twenty-one-year partnership for erecting one or more inoculating hospitals in the other colonies from Pennsylvania northward.18 The movement by Boston’s physicians to take much of the town’s potentially lucrative normal obstetrical practice away from the midwives actually began with James Lloyd in the 1750’s, but it was in the 1760’s that his example and rationale for greatly constricting the role of midwives began to have considerable effect, especially among his students.19 Lloyd’s fees at this time indicate that midwifery could indeed be profitable. He charged £1.8s. for normal and £4 for difficult deliveries. By comparison, he charged is.4d. to extract a tooth, 3 to 6s. for a visit or to change a dressing, and £4 for an infrequent capital operation.20

The 1760’s also witnessed a quickening impulse toward the improvement of medical education throughout British North America, and Boston was no exception, although here it did not result in the founding of a medical school as it did in Philadelphia. In Boston the most immediate effect was to be seen in the expanded use of a more organized, broadened, and sophisticated method of training medical apprentices and pupils. This included the encouragement of a step-by-step study of medicine, usually beginning with anatomy and ending with physic and a smattering of other sciences, a greater emphasis on reading both basic and recentmedicalliterature, and the employment of at least an occasional lecture making use of aids such as charts, illustrations, models, skeletons, and anatomical preparations. Admittedly, the roots of this movement go back at least to Silvester Gardiner in the 1740’s, but it was not until the 1760’s, when James Lloyd and his protégé, Joseph Warren, rose to preeminence among Boston’s medical preceptors, that these improvements became well established. Between 1760 and 1775 these two trained ten—or better than one-fifth—of Boston’s physicians of the era 1760–1790, including such leaders as John Clark vi, William Eustis, John Jeffries, Lemuel Hayward, Isaac Rand, Jr., David Townsend, and John Warren.21 What is more, their other students, like Ebenezer Allen, Isaac Foster, Jr., Peter Oliver, Jr., Jonathan Norwood, and Theodore Parsons, distinguished themselves elsewhere. Undoubtedly, Lloyd’s and Warren’s efforts benefited greatly from the large number of European trained physicians in Boston at this time, the stiff competition, and the area’s fine system of public education.

A very fruitful insight into the Boston medical-political dialectic of the Revolutionary era can be gained by comparing the students of Lloyd and Warren. All were Harvard graduates. None of Warren’s went on for further medical education, while four of Lloyd’s went to Europe, and Jeffries earned an M.D. All of Warren’s were strong Whigs, and at least five served in the Continental Army, while Lloyd’s were politically divided, with three serving with the British forces and one with the Continental Army.

In addition to the work of Lloyd and Joseph Warren, there was a serious attempt by others in the Boston medical community during the decade before Lexington and Concord to deal with the most crucial defect of the apprenticeship system, the shortage of cadavers for the direct study of the human body.22 In 1765, 1768, and 1774 public lectures on anatomy, making demonstrations on a cadaver, were offered by William Lee Perkins, Benjamin Church, Jr., and John Jeffries, three of New England’s most skilled surgeons.23 However, Jeffries was stopped after one lecture when a mob made off with his subject, an excellent example of the great danger and unpopularity at this time of this vital form of medical teaching.24 Because of this, it seems highly likely that anatomical study in Boston during this period was advanced by the occasional theft of a corpse. Another important manifestation of concern with improving anatomical study was the founding at Harvard in the late 1760’s of a semisecret student “Anatomical Society,” also known as the “Spunks” or “Spunkers.” This society seems to have received its inspiration from Joseph Warren, and his brother, John, was the club’s most important member, if not its founder. They owned a skeleton, discussed anatomical, physiological, and other medical questions, and dissected animals, chiefly horses, swine, dogs, and cats.25 Given the energy and daring of some of its members as well as that of Joseph Warren, their strongest outside supporter, they also may well have secretly dissected a cadaver or two.

Although no medical school was established in New England’s foremost city until 1782, there was considerable activity to bring about the establishment of one for well over two decades prior to this. In 1764, the Boston Post-Boy and Advertiser, commenting on the disastrous fire at Harvard on 24 January of that year which had destroyed most of Harvard Hall, including the library, noted that among the losses were:

a collection of the most approved medical Authors, chiefly presented by Mr. James, of the island of Jamaica; to which Dr. Mead and other Gentlemen have made very considerable additions; Also anatomical cuts and two complete skeletons of different sexes. This Collection would have been very serviceable to a Professor of Physic and Anatomy, when the revenue of the College should have been sufficient to subsist a gentleman in this character.26

Just how long and how seriously Harvard had been thinking of a medical school or professorship before this time is a moot point. A human skeleton and a preparation of the “human veins and Arteries filled with wax” had been presented to Harvard as early as 1748.27 At any rate, the losses due to the fire of 1764 were more than replaced within several years.28 However, the impression remains that the idea of providing some sort of advanced medical education did not attain an energetic focus until Ezekiel Hersey’s bequest of 1,000 Massachusetts pounds (750 pounds sterling) to support a professorship in anatomy and physic. This bequest was made in 1770 and received in 1772.29 After this, the Harvard Corporation began to move in earnest. At their meeting of 7 December 1772 the following resolution was passed:

That the thanks of this Board be given to the Revd. Dr. Erskine for his kind service in consulting Drs. Munro [sic] and Cullen on the subject of a Professorship of Anatomy and Physic at Harvard College and for transmitting their thoughts in so very obliging a manner as he has done. They also ask this further favor that he would express the grateful acknowledgement of the Board to the said gentlemen for the notice they have taken of the affair of a Professorship, and to acquaint them that Dr. Hersey’s bequest has lately been paid into the College Treasury. Vizt. seven hundred and fifty pounds sterling [.] That they hope for additions by donations as well as by interest [.] That benefactors are from time to time adding to the Medical Library and Anatomical preparations. That when the funds are sufficient to support a Professor and it shall be thought best to send abroad for one, particular attention will be paid to the recommendation from Edinburgh.30

This little-noted resolution seems to indicate that had not Massachusetts shortly become engulfed in the turmoil of war and revolution, Harvard would have instituted medical instruction on a formal basis well before 1782. It also suggests that medical teaching at Harvard, as was the case with Yale, would have begun with a single professorship within the college. What is more, medicine at Harvard, like that at the College of Philadelphia and King’s College at New York, would have had its start within a cosmopolitan imperial context rather than a self-consciously nationalist one. Furthermore, none of the original faculty could have played a role in the school’s founding, or probably its early history.

In the 1770’s Harvard was not alone in showing an interest in establishing a more advanced form of medical education in the Boston area. In late 1774 and early 1775, a recently arrived French “physician and surgeon” by the name of Dastuge (Dastugne, Dasturge) who claimed to have studied under “the best Professors in Physic and Surgery of the Royal Academy in Paris” and who said he had enjoyed “constant Practice in several Hospitals, both in France and the West Indies,” overflowing with ambition, naïveté, and brashness, issued a call in the Boston newspapers for the physicians and surgeons of the city to “meet and form a Corps, unanimously” and build a large amphitheater where medical instruction, especially in anatomy and surgery, could be given. Also, if properly encouraged, Dastuge would start a botanical garden and give lectures in botany and chemistry. Between 1777 and 1783 this irrepressible Gaul was in New York, where he placed a series of notices in the city’s newspapers advertising his skills as a surgeon, oculist, and dentist. In one of these notices he stated that he had attended the Hôtel Dieu and the Charité in Paris.31 That a market for advanced medical instruction existed in Boston at this time is well illustrated by the fact that at least seven of the forty eight members of the Harvard class of 1772 went on to become physicians.32

Curiously enough, despite their interest in furthering the development of professional awareness, Boston physicians seem to have played only a small role in the abortive attempt in 1765 to establish a colony-wide medical society.33 However, in 1768 members of Boston’s medical community may have supported an unsuccessful attempt to get a bill through the General Court requiring the examination of candidates for regular medical practice.34

With the shots exchanged between British regulars and Massachusetts farmers at Lexington Green the movement toward increasing the professionalization of medicine in Boston entered a new phase. Over the next five years the city’s permanent population fell from 16,000 at the beginning of the siege in April 1775 to less than 4,000 at its end in March 1776; it then climbed to approximately 12,000 by 1780.35 During this time Boston was wracked by inflation, profiteering, social dislocation, substantial population turnover, and, most melancholy of all, a long list of casualties.36 In 1775 the permanent population of physicians was around twenty-one. By 1776 it had fallen to about twelve.37 By 1780 it was up to at least fourteen.38 The city also experienced a kaleidoscope of medical men connected with the Continental Army and Navy, the state navy and militia, the numerous privateers, and possibly a few civilian doctors who resided there temporarily. In addition, the medical men connected with the French forces had a decidedly positive impact on Boston medicine. It almost certainly was one of these French doctors who gave John Warren his prized copy of Sabatier’s Anatomy. Another communicated to Samuel Danforth, the town’s leading student of chemistry, the advances his countrymen were making in that study. In June 1782 the Harvard Corporation voted to award one Monsieur de la Roche, a surgeon major in the French army, the honorary degree of Bachelor in Physic, although apparently it was never actually conferred. La Roche donated a copy of Bonmaris’s Dictionary of Natural History to the college library. The most influential of all these Gallic medical allies, though, was Jean Feron, “first surgeon and physician of the French fleet in North America and of the King’s hospitals in Boston,” who, in October 1783 was among the original honorary members elected to the Massachusetts Medical Society. Feron presented two anatomical preparations to the society and communicated to them three histories of remarkable skull fractures.39 He also read one of the first papers before that body, in July 1784. In addition, he performed a chemical analysis of the waters of the Boston peninsula at the request of John Warren, his warm friend, who was legitimately concerned about their salubrity.40

The siege of Boston which began the Revolution was not only a vital political, social, and military event in the city’s history, but also of great importance to her medical development as well. At the end of it there was a huge void in her community of physicians. Joseph Warren was dead, Benjamin Church, Jr., was a convicted traitor, Miles Whitworth, Sr., was in jail and soon to die of a fever contracted there, while Silvester Gardiner, John Jeffries, and Nathaniel and William Lee Perkins had gone into exile with the evacuating British forces. This loss amounted to about one-third of the physicians then practicing in Boston and much more than that in terms of talent, experience, and leadership. Such a gaping hole facilitated two somewhat contradictory developments. One was the rehabilitation, after a brief period of harrassment, of the town’s five remaining Tory doctors (Samuel Danforth, Thomas Kast, James Lloyd, James Pecker, and Isaac Rand, Jr.), for their skills were badly needed. The other was that it allowed younger Whig physicians, despite the fact that most of them served varying lengths of time in the service, to enter Boston practice and move rapidly up the ladder, exerting a far greater influence than they could have under pre-Revolutionary conditions. Indeed, most of them probably never would have become Boston physicians without the Revolution. These younger Whig medical men included Nathaniel Walker Appleton, Aaron Dexter, William Eustis, Lemuel Hayward, John Homans, David Townsend, and Thomas Welsh. However, the greatest beneficiary was the highly able and thoroughly ambitious John Warren, who was to be the dominant force in Boston medicine from the time of his return in the spring of 1777, to assume command of the Continental Army Hospital, until his death in 1815. Of course, being the brother of a war hero also facilitated his rise to prominence.

By 1780, despite five exhausting years of war and the fact that the cause of independence was as precarious as it ever had been, both Boston and its medical community were able to rejuvenate themselves to the point at which, over the next three years, there would be an explosion of social and institutional creativity. This included the founding of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Massachusetts Humane Society, and the Massachusetts Charitable Society in 1780.41 In the first two of these, Boston medical men played important roles. Three other foundings involved what most physicians thought would facilitate professional medical development. These were the Boston and Massachusetts medical societies and the Harvard Medical Institution.

The Boston Medical Society was founded in May 1780. It was composed of all the physicians of the city, both Whig and Tory, save Thomas Bulfinch, Jr., who declined membership but supported the society’s goals.42 The initial purpose of this new medical body was economic. It established a fee table which, with adjustments, lasted until the twentieth century. The following year its members agreed to insist upon immediate payment in obstetrical cases.43 It was also to this society that John Warren first turned with his scheme for providing Boston with advanced medical instruction.44 He pointed out to his fellow members that there were nearly a dozen medical apprentices and pupils within the town and that some sort of medical school should be established to meet their needs. Undoubtedly certain of being appointed the instructor in anatomy and surgery, he suggested that the influential Samuel Danforth teach materia medica and chemistry, a logical choice since he was the local physician most familiar with chemistry, although his knowledge was still quite limited, and that the learned Isaac Rand, Jr., teach the theory and practice of physic. Danforth and Rand, both of whom were Tories and highly suspicious of Warren, refused. However, although he failed in his initial attempt to get a medical school, this incident well illustrates Warren’s imagination, drive, and political skill. What is more, the society did sponsor Warren’s first public anatomical lectures, given in the winter of 1780–1781.

The Boston Medical Society also was the parent of the Massachusetts Medical Society in that its members were the original petitioners for its incorporation when the bill was presented to the state legislature in May 1781.45 By the time the bill was enacted on 1 November, they had been joined by the newly arrived Aaron Dexter and sixteen prominent physicians outside of Boston to form the thirty-one incorporators of the Massachusetts Medical Society.46

This society, which was patterned after the British model in being composed of fellows and licentiates, had three major early goals.47 In keeping with the injunction in its charter, it was to examine candidates for practice in physic and surgery, and to award certificates of approval. They did not “license” medical practitioners in the sense of excluding all others but, again in the British tradition, tried to distinguish between those they considered well qualified and those they considered to be less so or not at all. Secondly, the society sought to promote and disseminate medical and scientific knowledge. This they did through a lively and extensive correspondence both in America and abroad, the accumulation of a fine library,48 and, eventually, the publication of the Society’s Communications. Lastly, they worked to achieve a sense of collegiality and good will among their members. In all of these areas the society inevitably was subject to difficulties and disappointments, but in all they were fundamentally successful.

Two other aspects of the early Massachusetts Medical Society should also be noted. One is that, until its reorganization in 1803, it was almost totally dominated by the Boston medical community. Better than two-thirds of its executive officers, counselors, and censors were Bostonians.49 Its meetings were held in Boston, as were its examinations, and its library was there. The other is that the city’s five Tory physicians, all of whom had been founders, played particularly influential roles in the society. Danforth and Rand, Jr., became its presidents, Pecker the first vice president, and Kast a treasurer.50 Lloyd presented the Society’s bill of incorporation to the legislature, helped to draw up its first bylaws, served on the original board of counselors, and was an aggressive censor.51

Unlike the Boston and Massachusetts medical societies, the Harvard Medical Institution was an exclusively Whig affair. It was also, as Benjamin Rush observed, the first medical school to be established within a national rather than an imperial context.52 All three of its original faculty—Aaron Dexter, John Warren, and Benjamin Waterhouse—were staunch Whigs. Of the three, only Waterhouse had had any formal medical education above the apprenticeship level, and only Waterhouse had enjoyed a European medical experience. However, Dexter had seen some, and Warren considerable, military medical service, a common and beneficial form of auxiliary medical training in eighteenth-century America, with its opportunities to encounter a wide range of diseases and surgical problems, to broaden one’s social and medical outlook by coming into contact with more experienced and better-trained doctors, especially those from Europe, and to work in hospitals. Twenty of the forty-seven Boston physicians listed in Appendix I (forty-three percent) had had military medical experience. All three of these men were to have long careers on the Harvard medical faculty. Waterhouse served for twenty-eight years, Warren for thirty-three, and Dexter for thirty-four. This gave the early years of the Harvard Medical Institution both stability and a sense of continuity. Another stabilizing influence during the early years of the Institution was the tight control the Harvard Corporation exerted over it until it moved out of the college and over to Boston in 1810.53

As is well known, among the three original members of the faculty of the Harvard Medical Institution, Waterhouse was odd man out.54 There were many reasons for this. He was something of an outsider from the beginning, being from Rhode Island and raised a Quaker. Furthermore, while Dexter, Warren, and most of Harvard embraced the cause of high Federalism, Waterhouse moved in the opposite direction, going from moderate Federalism to ardent Jeffersonianism. What is more, there was widespread jealousy over the Rhode Islander’s superior education, which he never ceased to flaunt. Most important of all, though, were Waterhouse’s abrasive and combative personality and the fact that he had spent the Revolution traveling and studying in Europe while Dexter and Warren were at home fighting for the holy cause of independence. Still, even taking into account Waterhouse’s eventual dismissal in 1810, internal quarreling during the early years of the Harvard Medical Institution was really quite limited in comparison to that in most of America’s early medical schools.55 The really serious problems facing the Institution during its Cambridge years (1782–1810) were securing adequate numbers of both cadavers and “teaching patients,” and these were never overcome.56

The two men immediately responsible for the founding of the Harvard Medical Institution were John Warren and the recently installed President Joseph Willard, who as a youth had contemplated becoming a physician and who throughout his life remained a frustrated scientist.57 The second of Warren’s three sets of anatomical lectures given between 1780 and 1782 proved to be the prime catalyst.58 As mentioned before, these were sponsored by the Boston Medical Society and were given at the Continental Army Hospital during the winter of 1781–1782. They were surprisingly public and were attended not only by physicians and medical students, but by a number of laymen as well, including President Willard and other members of the Harvard Corporation and a few Harvard students. Following these lectures Willard arranged to have Warren draw up a plan for a medical school, and then secured its acceptance by the Harvard Corporation and Board of Overseers. Following this, Warren, 29, was appointed Professor of Anatomy and Surgery; Waterhouse, 28, Professor of the Theory and Practice of Physic; and Dexter, 33, Professor of Chemistry and Materia Medica.59 These men were inducted in October 1783, and their inaugural lectures were delivered on the first Friday in December of that year.60 Dexter’s lectures on chemistry were the first offered on that subject in New England.61 In 1788 Waterhouse began a senior elective course on natural history (biology and mineralogy), the first systematic treatment of these subjects at Harvard.62 He also established a mineralogical and zoological cabinet and a botanical garden. Both men’s efforts illustrate the large role played by physicians and medical schools in early American science.63

In the twenty years following the Revolution Boston first underwent a serious depression, lasting until 1787, and then enjoyed her first significant economic, physical, and population growth in well over a generation.64 Her permanent population, which had been around 12,000 in 1780, rose to 18,320 by 1791 and to 24,937 by 1800.65 Between 1780 and 1789, when the first Boston Directory was published, the number of Boston physicians rose from fourteen to at least twenty-four, an increase of seventy percent.66 Over the next decade, with continued prosperity and population growth, the number of physicians increased by another thirty percent. The Directory of 1796 listed twenty-six, and that of 1798, thirty-one.67 Of the physicians who entered practice in the city between 1780 and 1798, apparently only two had studied in Europe.68 However, during the same period, five new physicians, three of whom were to have impressive careers, were graduates of the Harvard Medical Institution.69 In addition, Amos Windship, a veteran practitioner and versatile scoundrel, also earned an M.B. degree there in 1790.70

Between 1783 and 1796 the dominant theme of Boston medicine was that of conflict and adjustment to the new institutional-professional milieu which had been created so rapidly. There were two important manifestations of this. One was the successful effort in 1784 of the Boston Medical Society to deny students of the Harvard Medical Institution access to the infirmary at the Boston Almshouse and to kill a bill which would have allowed Harvard to establish a public infirmary in Cambridge.71 The other was a two-pronged struggle between Harvard and the Massachusetts Medical Society.72 The first issue involved the right of the Harvard Medical Institution to issue certificates of approval to her students prior to their receiving a degree, a procedure which Harvard quickly abandoned upon protest by the Medical Society. The other, more difficult, issue involved a decade-long struggle over the right of the Medical Society to examine and certify Harvard medical graduates. This quarrel eventually resulted in an agreement whereby either a certificate of approval by the Massachusetts Medical Society or a medical degree from the Harvard Medical Institution would constitute a duly qualified physician. Actually, not until 1803 did the legislature recognize that a Harvard medical degree was the equivalent of a certificate of approval.73

One other event of this period also should be noted. In 1786 James Lloyd sent his former student and present associate, John Clark vi, to London to study midwifery and to collect appropriate instruments and teaching devices in order that he might lecture on the subject when he returned.74 At this time, and for many years thereafter, the only regular obstetrical instruction at the Harvard Medical Institution was a lecture in midwifery in Warren’s anatomy course.75 Unfortunately, Clark gave only one set of lectures before he died.76 It is interesting to conjecture what might have happened had Clark been able to establish at this early date a successful tradition in Boston of private medical courses wholly independent of Harvard. Certainly Boston medicine would have been more interesting. Probably it would have been less successful.

By the middle 1790’s Boston medicine had achieved a new synthesis based on the Harvard Medical Institution and the Massachusetts Medical Society, and between 1796 and 1803 the city underwent another period of medical creativity. In 1796 the Boston Dispensary was established, the third such institution in the country.77 Here free medicines and medical advice were given by selected physicians to the sick among the “worthy” poor who had been recommended by subscribers; the whole operation was supervised by a lay board of trustees. In 1799, a Board of Health was formed as a direct result of the yellow fever epidemic of the previous year.78 This Board, elected by ward annually, consisted of twelve respected citizens from varied economic and political backgrounds. In 1802 the Board of Health, Benjamin Waterhouse, and the leading physicians of Boston, after winning support at a town meeting, combined to conduct one of the most sophisticated and successful human experiments in American medical history to demonstrate conclusively the efficacy of vaccination.79 On 16 August of that year nineteen volunteer boys, including two sons of members of the Board of Health, were vaccinated before the Board at their office. A week later the participating physicians examined them and declared them to be “fit subjects” for the ensuing experiment. A temporary hospital was built on Noddle’s Island and, after some difficulty, fresh smallpox matter was obtained. Then, on 9 November, twelve of these boys, plus the son of Dr. Josiah Bartlett, who had been vaccinated two years earlier, were inoculated along with two unvaccinated youths. All were lodged in one room, given no medicines and allowed to follow, insofar as possible, their normal life style. The unvaccinated boys contracted smallpox and suffered heavily. The vaccinated ones did not. Then the thirteen vaccinated boys were inoculated again, along with the seven vaccinated volunteers who had not been inoculated previously. All remained in the single room with the two smallpox sufferers. Still none of them came down with the hated malady. Finally, in mid-December, a description of this experiment along with a strong endorsement of vaccination by eleven of the participating physicians, all of them distinguished and influential, was published by the Board of Health in a broadside. The same year a short-lived but initially busy vaccine institution was set up to serve the city’s poor and assure a fresh supply of vaccine.80 Finally, in 1803 the Massachusetts Medical Society was reorganized successfully to allow for full participation in the Society by any reputable physician, for the creation of district medical societies, and for conducting examinations in various parts of the state.81 These revisions greatly facilitated the linking of Boston medicine to that of the rest of the commonwealth.

In 1803, Boston still lacked public facilities for the insane, a medical journal, and, most important of all, a general hospital. Nonetheless, her medicine had reached a level of professional quality and maturity which allowed it to enter the mainstream of western medicine as witnessed by the famous Brahmin-Paris alliance of the next two generations of Boston physicians.

The last half of the eighteenth century was a difficult yet momentous period in Boston’s history. The city endured two depressions, a revolution, and the ordeal of adjusting to independence before finally, in the 1790’s, entering a period of stability, prosperity, and growth. Throughout the entire time Boston physicians played prominent political and social as well as medical roles. Collectively these men were ambitious, hard-headed, and strong willed. They enjoyed a high degree of racial and cultural homogeneity which helped to heighten their sense of civic pride and responsibility. Yet they were also extremely combative and contentious. Despite this, between 1760 and 1803 they made great strides in professionalizing Boston medicine by working to control and advance first smallpox inoculation and then vaccination, to extend control over obstetrics, and to improve medical training and the dissemination of medical information. They also founded two professional societies and worked to establish and maintain standards for recognition as duly qualified medical practitioners. Their attitude toward the establishment of New England’s first medical school certainly was mixed, but they soon came to recognize it as a valuable agent and ally in the struggle to control and improve medical standards and to increase the physician’s authority as a health expert. As a result, Boston medicine was much more professionalized both institutionally and in attitude in 1803 than in 1760.

Boston Physicians,* 1760–1798

| Name | Dates | College | Advanced med. ed. | Military med. exp. | Religion | Politics | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Adams, Samuel, Jr. |

1751–1788 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

2. Appleton, Nathaniel Walker |

1755–1795 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

3. Brown, Samuel |

?–1805 |

Harvard |

Harvard Med. (m.b.) |

no |

Cong. to Swedenborg. |

— |

||||||||||

|

4. Bulfinch, Thomas, Jr. |

1728–1802 |

Harvard |

London and Edinburgh (m.d.) |

no |

Ang. to Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

5. Cheever, Abijah |

1760–1843 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

6. Church, Benjamin, Jr. |

1734–1778 |

Harvard |

London |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

7. Clark, John, iv |

1698–1768 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

— |

||||||||||

|

8. Clark, John, vi |

1753–1788 |

Harvard |

London |

yes |

Cong. |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

9. Clark, William |

1725–1787 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

10. Curtis, Benjamin |

1753–1784 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

11. Danforth, Samuel |

1740–1827 |

Harvard |

London |

no |

Cong. |

Tory-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

12. Danforth, Thomas |

1775–1817 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Ang. |

Fed. |

||||||||||

|

13. Dexter, Aaron |

1750–1829 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

14. Doubt, Nyott |

1727–1764 |

Harvard |

London |

no |

Ang. |

— |

||||||||||

| Dates | College | Advanced med. ed. | Military med. exp. | Religion | Politics | |||||||||||

|

15. Erving, Shirley |

1759–1813 |

none |

no |

no |

Ang. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

16. Eustis, William |

1753–1825 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Jeff. |

||||||||||

|

17. Fleet, John, Jr. |

1766–1803 |

Harvard |

Harvard Med. (m.b., m.d.) |

no |

Cong. |

Fed. |

||||||||||

|

18. Gardiner, Silvester |

1710 or 1727–1788 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

19. Gardner, Joseph |

1708–1786 |

none |

London and Paris |

no |

Ang. |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

20. Hayward, Lemuel |

1748/9–1821 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

21. Homans, John |

1753–1800 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

22. Hunt, Ebenezer |

1744–1820 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

23. Ingalls, William |

1769–1851 |

Harvard |

Harvard Med. (m.b., m.d.) |

no |

— |

Fed. |

||||||||||

|

24. Jarvis, Charles |

1748–1807 |

Harvard |

London |

no |

Cong. |

Whig-Jeff. |

||||||||||

|

25. Jeffries, John |

1744–1819 |

Harvard |

London, Aberdeen (m.d.) |

yes |

Cong. to Ang. |

Tory-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

26. Kast, Thomas |

1750–1820 |

Harvard |

London |

yes |

Ang. |

Tory-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

27. Linn, John |

1750–1793 |

none |

no |

yes |

— |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

28. Lloyd, James |

1728–1810 |

none |

London |

no |

Ang. |

Tory-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

29. Marshall, Samuel |

1735–1771 |

Harvard |

London |

no |

Ang. Cong. |

— |

||||||||||

|

30. Mather, Thomas |

1713–1764 |

none |

no |

no |

— |

|||||||||||

|

1723/4–1794 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong, to Ang. |

Tory-Fed. |

|||||||||||

|

32. Perkins, John |

1698–1780 |

none |

London |

no |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

33. Perkins, Nathaniel |

1715–1799 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

34. Perkins, William Lee |

1737–1797 |

none |

London (possible m.d.) |

yes |

Ang. |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

35. Rand, Isaac, Sr. |

1719–1791 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

36. Rand, Isaac, Jr. |

1743–1822 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Tory-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

37. Smibert, Williams |

1733–1774 |

none |

Edinburgh (m.d.) |

no |

— |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

38. Spooner, William |

1760–1836 |

Harvard |

Edinburgh (m.d.) |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

39. Sprague, John |

1718–1797 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

40. Townsend, David |

1753–1829 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. to Univ. |

Whig-Jeff. |

||||||||||

|

41. Warren, John |

1753–1815 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

42. Warren, Joseph |

1741–1775 |

Harvard |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig |

||||||||||

|

43. Welsh, Thomas |

1751–1831 |

Harvard |

no |

yes |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

44. Whipple, Joseph |

1756–1804 |

none |

no |

no |

Cong. |

Whig-Fed. |

||||||||||

|

45. Whitworth, Miles, Sr. |

1715–1778 |

none |

no |

yes |

— |

Tory |

||||||||||

|

46. Windship, Amos |

1745–1815 |

Harvard |

Harvard Med. (m.b.) |

yes |

Cong. to Ang. to Meth. |

Whig-Jeff. |

||||||||||

|

47. Young, Thomas |

1731–1777 |

none |

no |

yes |

Freethinker |

Whig |

||||||||||

*As defined in n. 3, 70.

Physicians* Listed in the Boston Directories of 1789, 1796, and 1798

| Name | 1789 | 1796 | 1798 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1. Appleton, Nathaniel Walker South Latin School Street, near Stone-Chapel |

X |

||||||

|

2. Bertody, Francis Leverett Street |

X |

X |

|||||

|

3. Bulfinch, Thomas, Jr. Bowdoin Square Cambridge Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

4. Cheever, Abijah Hanover Street Federal Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

5. Danforth, Samuel Tremont Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

6. Dench, Gilbert, Jr. Ann Street |

X |

||||||

|

7. Dexter, Aaron Milk Street, opposite rope-walk |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

8. Dix, William Back Street |

X |

||||||

|

9. Enslin, John Frederick Battery-march Street Blind Lane |

X |

X |

|||||

|

10. Eustis, William Sudbury Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

11. Fay, Nahum Fleet Street Garden Court |

X |

X |

|||||

|

12. Fleet, John Milk Street No. 5 Cornhill |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

13. Hall, Percival Charter Street |

X |

||||||

| Name | 1789 | 1796 | 1798 | ||||

|

14. Hayward, Lemuel Newbury Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

15. Homans, John No. 6 Marlborough Street Lincoln Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

16. Hunt, William Ship Street, house, Hanover Street |

X |

||||||

|

17. Ingalls, William No. 15 Union Street |

X |

||||||

|

18. Jackson, William No. 29 Union Street |

X |

||||||

|

19. Jarvis, Charles Common Street Winter Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

20. Jeffries, John Tremont Street |

X |

X |

|||||

|

21. Kast, Thomas Fifth Street Hanover Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

22. Leavitt, Josiah Staniford Street |

X |

||||||

|

23. Lloyd, James Tremont Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

24. Parker, Henry Pleasant Street |

X |

||||||

|

25. Pecker, James Hanover Street, corner of Friends Street |

X |

||||||

|

26. Peters, Alexander Abercrombie Marlborough Street |

X |

||||||

|

27. Rand, Isaac, Jr. Middle Street, just below Cross Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

28. Rand, Isaac, iii† Hanover Street |

X |

||||||

| Name | 1789 | 1796 | 1798 | ||||

|

29. Read, William Milk Street |

X |

||||||

|

30. Rogerson, Robert Ship Street |

X |

||||||

|

31. Smith, Nathaniel corner Garden Court and Fleet Street |

X |

||||||

|

32. Spooner, William Cambridge Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

33. Sprague, John, Jr. Federal Street |

X |

X |

|||||

|

34. St. Medard, Peter‡ Garden Court, North Square Back Street |

X |

X |

|||||

|

35. Thomas, Joshua A nne Street, house, Liberty Square |

X |

||||||

|

36. Townsend, David§ Southack’s Court Middle Street Pleasant Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

37. Warren, John South Latin Street, next to Cromwell’s Head South School Street School Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

38. Welsh, Thomas Sudbury Street Hanover Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

39. Whipple, Joseph Orange Street South Bennet Street |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

40. Windship, Amos Hanover Street, near the Mill-bridge |

X |

X |

|||||

*As defined in n. 3, 70.

† In the 1798 Directory Isaac Rand, Jr., becomes Sr., while Isaac Rand the third is Isaac Rand, Jr. For purposes of clarity I have kept Isaac Rand, Jr., as Jr. and called Isaac Rand the third Isaac Rand III.

‡ Listed as “surgeon.”

§ Townsend is listed as “Inspector of nails and potash,” which he was, but he continued to practice medicine as well. For details of his practice, see J. Worth Estes, “Therapeutic Practice in Colonial New England” below, 289–383.

PHILIP CASH

PHILIP CASH