APRIL MEETING, 1924

A STATED MEETING of the Society was held, at the invitation of Mr. William C. Endicott, at No. 163 Marlborough Street, Boston, on Thursday, April 24, 1924, at eight o’clock in the evening, the President, Fred Norris Robinson, Ph.D., in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

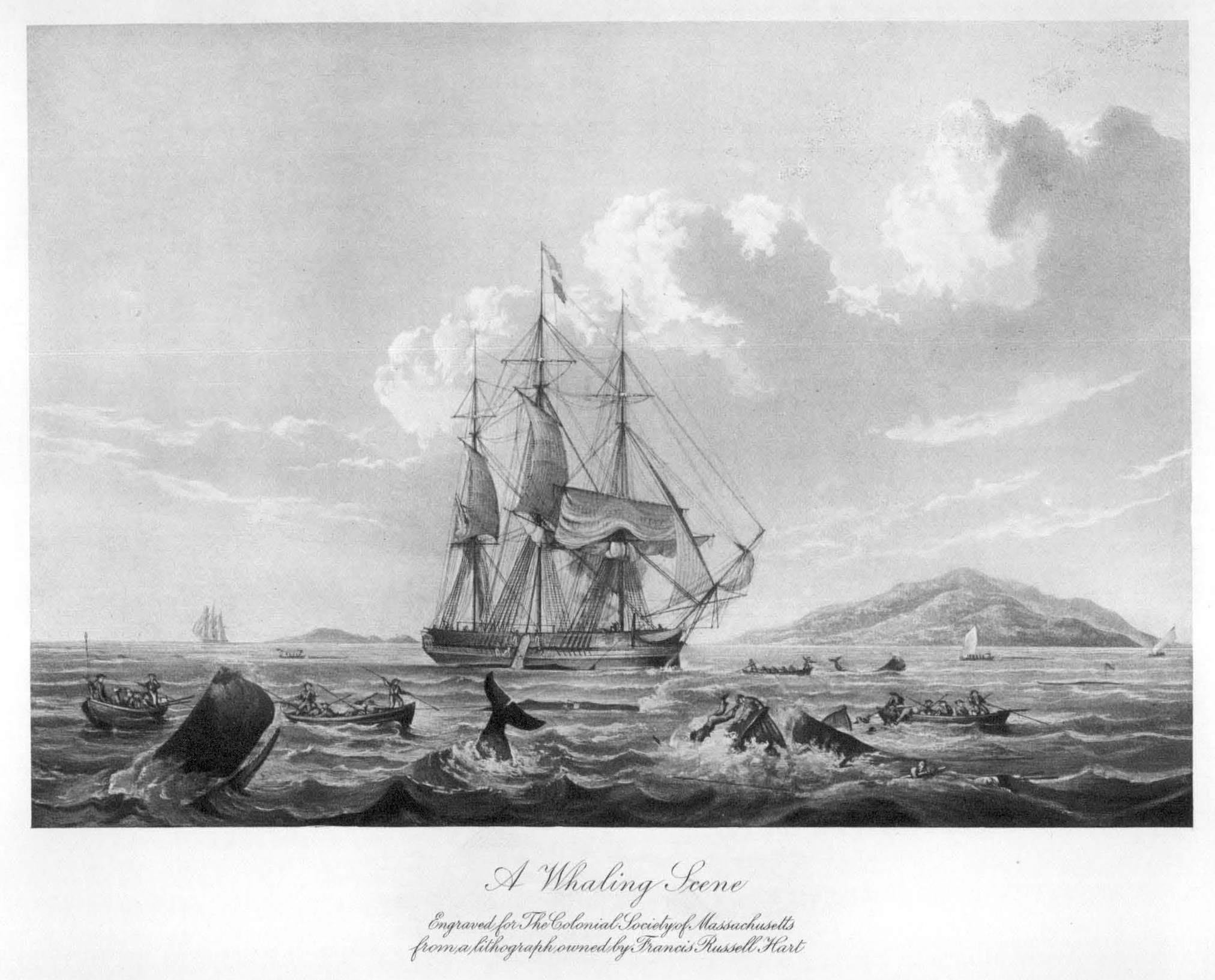

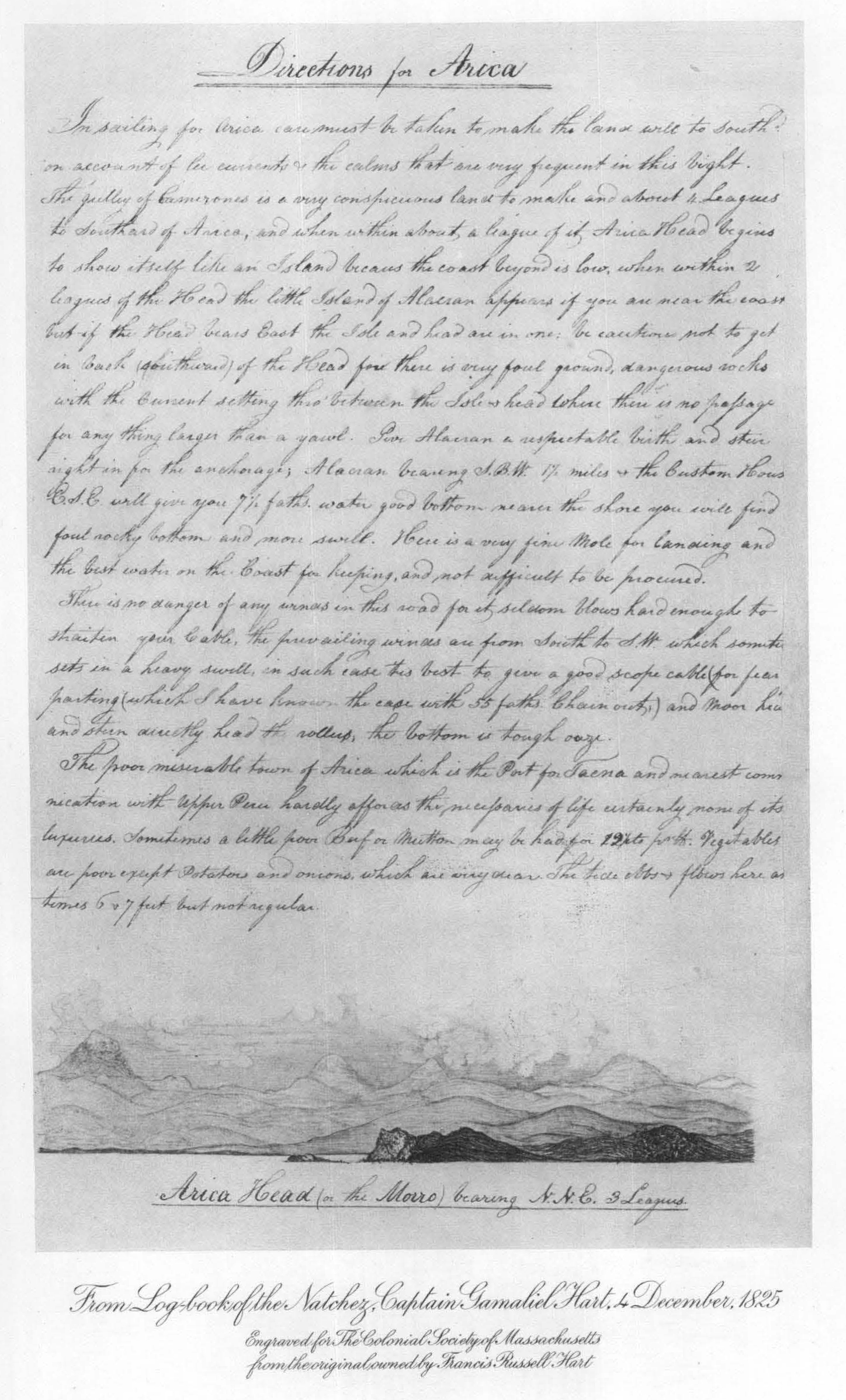

Mr. Francis R. Hart exhibited the log-book (1825–1828) of Captain Gamaliel Hart of the ship Natchez, and read the following paper:

THE NEW ENGLAND WHALE-FISHERIES

If the writer of so valuable and interesting a book as the Maritime History of Massachusetts can be charged with no greater faults than those of omission, he is indeed fortunate. Dr. Samuel E. Morison did the world, particularly that part which belongs to or is descended from New England, a very real service when he published the result of his researches into our maritime records. He himself points out certain alluring fields for further investigation; so that if one is tempted to wish that he had treated parts of his work with less brevity, this desire cannot fairly be expressed in a critical spirit. It is more reasonable to accept his implied invitation and endeavor to do what it is to be wished he had found time and opportunity to do in his own competent way. For these reasons I have ventured to prepare some notes on the New England whale-fisheries; the purpose being to supplement and amplify rather than to correct the interesting chapter which Dr. Morison devotes to this subject. It is proper to state, however, that in New Bedford, where live many of the descendants of those hard-headed and harder-fisted old sea-masters described by Dr. Morison, his description of whale-ship management is hotly disputed. Dr. Morison has been guided by recorded evidence, unsoftened by family traditions. The present-day critic in New Bedford has an intimate knowledge of the conditions affecting whale-ship management since 1860, and his convictions in respect to the earlier customs and methods are colored by more recent-day knowledge. Dr. Morison deals with the whale-fisheries up to 1860 only; and whilst I confess to a belief that a wider search in the early log-books and records would have softened, by the application of a benign “general average,” the somewhat over-strong language used by Dr. Morison, I cannot condemn as essentially inaccurate his description of the whale-fisheries prior to 1860. Many merchant captains were as despotic and cruel as the whaling masters. The suggestion that no man went whaling but once is disproved by the evidence. The sailor on a merchant ship did not suffer from the evil lay-system; but he had more continuous hard work and less leisure for the exercise of his talents in carving and other handicrafts.

It is not, however, in connection with these controversial matters that I have prepared my notes. It is my wish to record in convenient and brief form those causes which led to the establishment of the New England whale-fisheries, some of the effects of these fisheries on the life and character of our people, and the part which the whale-men played in the extension of American trade and discoveries.107

The early settlers of New England were in need of a greater supply of oils and fats than could be readily obtained from the animal resources at hand. Of necessity, the attention of any body of pioneers in a new country must be given to agriculture rather than to grazing, so that the supply of tallow and other animal fats was not enough for the purposes of illumination. The pine knot was at best an unsatisfactory substitute for the tallow dip or smoky lard-oil open lamp. The sea offered a more certain and, with all its dangers, a safer region for exploitation than the land, although the occasional bear or other well-nourished wild animal was valued perhaps as much for its fat as for its meat and fur.

It is recorded that among those on the Mayflower were several men experienced in fishing, who, when they arrived on this side, bemoaned the fact that suitable tackle for the capture of whales had not been brought on the ship. It is perhaps due to this record that we have not in our museums and private collections a shipload of whaling tackle alleged to have come over in the Mayflower.

Bradford and Winslow refer to the intention of certain persons to “fish for Whale” in Massachusetts Bay and to the great whales which off Cape Cod “swim and play about vs.”108 The Rev. Francis Higginson of Salem in 1629, in making a list of the commodities within the colony, includes a “great store of whales and crampusse.”109 It does not appear, however, that any early attempts were made actually to go out and capture live whales during the early years of the colony. Whales were from time to time cast up on the shore, which yielded a scanty but valuable supply of oil. Waymouth, in the journal of his voyage to America in 1605, describes the method of the Indians in killing whales.110

The first reference which I have found to the search for whales by Europeans in American waters is by Anthony Parckhurst, who in a letter to Richard Hakluyt dated 13 November, 1578, says, speaking of Newfoundland: “I am informed that there are above 100. saile of Spaniards that come to take Cod (who make all wet, and do drie it when they come home) besides 20. or 30. more that come from Biskaie to kill Whale for Traine.”111 The second is in an account by Silvester Wyet, dated 24 September, 1794, of “The voyage of the Grace of Bristol of M. Rice Jones … up into the Bay of Saint Laurence … for the barbes or fynnes of Whales and train Oyle.”112 The third is by Richard Norwood in his “Insularum de la Bermuda Detectio.”113 He says that men from the vessel Sea Venture stranded on the Bermudas in July, 1609, found in 1610 “a verie greate treasure in amber-greece, to the valew of nine or tenne thousand pound sterling.” He further describes that in 1617 there was sent out “a ship and prouision with men of skill for the killing of whales,” a venture which met with small success.

John Winthrop writing in April, 1635, refers to the going across the Bay of Cape Cod of some of the Massachusetts Bay Colony people to make oil from whales cast on shore, of which he says, “There were three or four cast up, as it seems there is almost every year.”114

Other evidence, the details of which I will not now give, makes it clear that “drift whales” and “stranded whales,” as they were called, were of not infrequent happening, and that the questions affecting the title to such whales were early causes of disputes among the colonists. The customs of the colonists in settling these disputes during the first thirty years or so after the landing at Plymouth, finally became statutory and the court records show occasional legal battles by rival claimants for a stranded whale. The General Courts of both the colonies of Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, as well as the local board of many of the settlements, adopted regulations in respect to the property rights in drift and stranded dead whales. The rules adopted followed English precedents.

In 1652 the town of Yarmouth115 appointed an officer “to receive the oil of the country” for that town, and the town of Sandwich116 appointed six men to supervise and regulate the cutting up and distribution of fish and whales. The subsequent records of Sandwich and of the Massachusetts Bay Colony indicate that this oil business from drift and stranded whales must have been of no mean proportions. The Massachusetts Bay Colony allotted one-third of the oil to the crown, one-third to the town, and one-third to the finder.

When the time came that whales were actually pursued in boats, the number of drift whales materially increased by reason of the wounded whales which had eluded capture eventually to die and be cast on the shore, an event which further complicated the question of title and brought new disputes and more regulations.

The General Court at Hartford, Connecticut, in May, 1647, granted certain privileges in respect to whale fishing to a prominent merchant of Hartford; except for this record there appears to have been little attention given in Connecticut to the industry. The greater distance of the Connecticut shores from the open sea would account for this.

Although there is more or less conflicting evidence as to where the first attempt at whale-fishing was organized as a business, it appears probable that the people of Southampton, Long Island, were the first really to adopt the search for whales as a calling for any appreciable part of its townfolk. Detailed and business-like regulations were adopted as early as 1647 and a few years later regular expeditions, often covering several weeks, in boats from the shore took place. The business spread to the neighboring towns, as new settlements were formed, and the eastern end of Long Island became an important factor in the early development of the American whale-fisheries.

The early records of Nantucket give scant mention of whales, and in 1690 the people, “finding that the people of Cape Cod had made greater proficiency in the art of whale-catching than themselves,” sent to friends on the Cape for a man to instruct them.117 The enterprise which Nantucket lacked in the beginning was compensated by the place the island subsequently took, in association with New Bedford, Fairhaven and Martha’s Vineyard, in the world whale-fisheries.

It would be tedious to trace the growth of the industry from these small beginnings of the colonists. It is enough to note that from the occasional finding of a stranded whale to the active search for live whales pursued by small boats from the shore, was a natural evolution. The growth of the colonies made inevitable the subsequent step of building and equipping ships fitted for long voyages. Not only had the needs of the people and the opportunities for a profitable export trade increased, but natural causes made it necessary to go further to find an adequate supply of whales.

In 1752, on Nantucket, John Newman and Timothy Coffin built a vessel of seventy-five tons. In Virginia, in 1751, a small boat called the Experiment was fitted out for whaling. It was probably not until several years later that vessels were equipped at Dartmouth and New Bedford, but in 1765 four sloops, the Nancy, Polly, Greyhound, and Hannah, owned by Joseph Russell, Caleb Russell, and William Tallman, were engaged in the business. The business grew rapidly and in 1768 eighty vessels were sent out from Nantucket alone, a number which by 1775 had increased to one hundred and fifty. A similar, if not quite so rapid, development took place at the other ports: Dartmouth, Boston, Cape Cod, and Rhode Island.

The effect of this business was not alone to furnish employment to those who manned the ships, but spread through the whole community. In many of the towns the chief activities became tributary to the whale-fisheries. The coast towns were busy with the making of rope, casks, blocks, iron-work, the building of and rigging of ships, as well as the many minor industries which contributed to the equipping and provisioning of rapidly growing fleets.

The industry bred a hardy race of men. To the ordinary dangers incidental to the voyaging about either of the great oceans for months in vessels of less than one hundred tons’ burthen and engaging in the dangerous business of capturing whales, was added the very real danger of capture by enemy ships. In certain waters French and Spanish privateers were almost as frequently sighted as whales. As early as 1755–1756 the Nantucket owners lost six vessels by their capture by the French. Armed conflicts and occasional losses of ships and lives were ever-present possibilities. The vessel sent out by Messrs. Newman and Coffin in 1752 was, on her second voyage, captured by the French on the Grand Banks, and Captain Coffin lost his life as well as his ship. In 1771 three Dartmouth ships were taken by the Spanish near Hispaniola.

Events of this kind stirred the adventurous spirit of the colonists and insured that the boats would not be manned, save by those ready to meet both the dangers of the sea and of war. The qualities of fortitude and endurance inherited from the early settlers and developed by the exigencies of a pioneer life fitted these strong and alert Yankees for the whaleman’s life, just as this life itself bred a race of self-reliant men whose influence has been and is still strong in the making and keeping of New England character.

That these masters and crews did not become ready prey to the Spanish and French privateers and pirates goes without saying. Equally quick in action and in strategy, an encounter was often avoided by the resourcefulness of the Yankee commanders.

In April, 1771, two Nantucket whaling vessels were at anchor in the roadstead of Abaco. A ship with distress signals flying was sighted off the port and the master of one of the American vessels, with a boat’s crew made up from the two ships, rowed out to give help. On climbing to the deck of the distressed ship he was ordered to pilot the vessel into the harbor, a pistol presented to his head enforcing the demand. With the help of one of his crew, more familiar than he with the harbor, and also urged by a loaded pistol, the Nantucket captain took the ship safely in and anchored her in a position where a point of land lay between her and the two Nantucket vessels. Whilst on board the strange ship he noted that the men were practically all armed and that one man appeared to be confined in the cabin. The conclusion was obvious that the crew had either mutinied and imprisoned the proper master in the cabin, or that the vessel was in the hands of pirates. After consultation the American captains invited the man who claimed to be the master of the strange ship to bring his own officers and passengers, if any, and dine on board one of the Nantucket ships. The pirate captain, with his boatswain and the real captain, described as a passenger, came on board. After dinner the pirate captain was seized and bound; the real captain was then free to tell his story. His vessel, he stated, was bound home from the West Indies with a cargo of sugar when the crew, desirous to become pirates, mutinied and took possession of the ship, imprisoning the captain and mate. Under promise of immunity and further urged by the quite unfounded statement that a man-of-war was within a few hours’ sail of the port, the boatswain was persuaded to return to his ship and with instructions to release and bring back the mate. Fortunately, at the same time he was told that when the help of the man-of-war had been obtained, a certain signal would be set. The boatswain did not return, as instructed, and one of the Nantucket vessels was got under way and started out as though to pass out of the harbor on one side of the pirates’ ship. The mutineers pulled such movable guns as the vessel carried, over to that side of their ship with the intention of sinking the smaller Nantucket ship (actually of the rig then called a sloop) as she passed by. By a quick manœuvre, however, the Nantucket boat passed on the other side of the pirates and out to sea. Within a reasonable time afterwards, and tacking out of sight of the pirate ship, the Nantucket sloop returned flying the agreed-upon signal that help had been secured from the man-of-war. The boatswain, seeing the signal and believing no escape possible from immediate capture, fled at once to the shore with all on board, save the true mate who was in irons. The mutineers were arrested on shore and the vessel itself was taken by the Nantucket men to New Providence, where a bounty of $2,500 was awarded them.

In 1772 two whaling vessels, also from Nantucket, were taken by a Spanish brig. In 1773 a Boston brig, while taking water on the coast of Sierra Leone, had a boat with six men seized by natives and all the men massacred. In the following year a Tiverton vessel and one from Boston while taking water at Hispaniola were seized by a French frigate. Another incident of about this time, somewhat difficult to believe, but reported in the Boston Post Boy of October 14, 1771, is that of an Edgartown whaling vessel which reported that one of her boats after striking a whale had been bitten in two by the whale and that Marshall Jenkins, one of the crew, had been taken into the mouth of the whale, which had then sunk with him; on returning to the surface, the whale had ejected him onto the wreckage of the broken boat, much bruised but not seriously injured. The Post Boy states that “This account we have from undoubted authority.”

The hope, often realized, of large profits and the lure of adventure attracted many stalwart men to this business of getting whales which was, perhaps, in spite of its commercial aspects, the greatest marine sport ever devised and partaking in many ways of the dangers and excitements which surrounded the pursuit of German submarines in the late war.

From 1784 the records of the shipping engaged in the whale-fisheries are nearly complete, but before that date collected official data are fragmentary.

In Massachusetts, in 1774, there were actually 304 vessels with an aggregate tonnage of 28,000 engaged in the business and a total for the colonies of probably 360 vessels. Starbuck estimates that in the four years from 1771 to 1775 the average annual production of oil had reached the relatively impressive figures of 45,000 barrels of sperm oil, 8,500 barrels of right whale oil, and 75,000 tons of bone.

Of all the industries of the colonies, it was not strange that the whale-fisheries should have been the first, or almost the first, to be affected by the growing disaffection of the colonies toward the mother-country. With Massachusetts, the actual centre of the growing insurrection, it was inevitable that a ministry wholly lacking in the capacity to realize and deal with the real issues, should seek to force the rebellious colonists to subjection by any ready means of punishment. Interference with the highly developed whale-fisheries was a means ready at hand. In February, 1775, the ministry, seemingly bent upon magnifying each of its errors by committing a new one, introduced into Parliament a bill restricting the commerce of Massachusetts and its neighboring colonies with England and the West Indies and prohibiting the carrying on of any fishery on any part of the North American coast. The details of the debates on this bill have no proper place in this paper, but it is of interest to note that the merchants and traders of London petitioned against the bill and an active minority in both houses worked zealously against it. The bill gave rise to an eloquent defence of the colonies by Burke. The bill became a law, and even before the 19th of April, 1775, the suspension of the American whale-fisheries had taken place. I will not dwell on the unhappy predicament of the whalemen then afloat, who were obliged when taken by an English man-of-war or privateer either to go on board a man-of-war and fight against their country or ship on board an English whale-ship.

One rather interesting arrangement was made in 1781 between the people of Nantucket and Admiral Digby, then in command of the English fleet in these waters. The situation of the people of Nantucket was serious in the extreme. Their only occupation had been taken from them. With the English fleet in their immediate proximity, even ordinary fishing was so difficult and dangerous that practically the island was without resources. Admiral Digby finally issued permits for twenty vessels to do ordinary fishing and for four to engage in the whale-fisheries. Difficulty was encountered in getting the Massachusetts authorities to ratify these permits, and such approval was only finally obtained just before the signing of the provisional treaty of peace with England.

With peace came the rebirth of the American whale-fisheries and the building and sending out of those great fleets, a few vessels of which are still afloat, and with the operation of which Dr. Morison’s account more particularly deals.

The importance of the whale-fishery was realized by this Commonwealth, which in 1785 granted a bounty on all whale oil brought into Massachusetts ports by vessels owned and manned wholly by inhabitants of the State. This bounty greatly stimulated the business, but caused such a rapid concentration of the trade in Massachusetts that markets were soon over-stocked. It was during this period of over-supply that Mr. William Rotch of Nantucket conceived the idea of transferring a large portion of the Nantucket whaling business bodily to the other side, where the market for the oils was a ready one. Negotiations with the English Government failed, however, as the Government was unwilling to pay the necessary expenses of moving the families and equipment of the shipowners to that side. Leaving England, Mr. Rotch went to France, and after very brief negotiations arranged for a transfer of the interests of his family and friends to Dunkirk. For several years the business here was successful, but impending troubles between France and England and other causes led Mr. Rotch to return with most of his vessels in 1794 to Nantucket, whence he moved the next year to New Bedford, at which place the industry started by Joseph Russell had already reached respectable proportions. The full story of the relations of the ship-owners and people of Nantucket in respect to English and French whaling is an interesting tale by itself and throws considerable light on many collateral events of the time.

The rapid revival of the American whale-fisheries after the war and the impetus given the trade by an increasing world consumption of both sperm and right whale oils made it necessary each year for the fleets to go farther from their home ports, which in turn brought about the need for larger ships. More and more men were employed to man these vessels, now almost exclusively brigs, barques, or even full-rigged ships, and it became necessary in due course to go farther afield for men.

The War of 1812 again put the whaling business in great jeopardy. The ship-owners of Nantucket, New Bedford and the vicinity had in particular no real belief that actual war would result from the disputes with England and no attempt had been made either to delay the sailing of vessels or to recall those at sea. A large number of ships were either captured or destroyed. Nantucket was again in desperate straits when early in 1815 the end of the war brought relief. The rapidity of the resumption of the business appears from the records to have been truly remarkable.

At the beginning of 1812 Nantucket had a fleet of forty-six whale-ships of which, at the end of the war, it had but twenty-three left; yet by the end of 1820 its fleet was made up of over seventy-two vessels. Prior to the nineteenth century the average size of the American whaling fleet had been under ninety tons, but in 1820 the average size of the vessels of the Nantucket fleet was 283 tons. The increasing slaughter of whales by those engaged in the fisheries of not only America but England, France, Holland, and the countries to the north, caused the more adventurous to seek new cruising grounds.

The pursuit of the sperm whale, by far the most valuable of the whale family, in particular called the ships farther and farther from home. From the West Indies and Cape Verde the ships went as far south as the Patagonian shores and finally up the Pacific coast of South America.

From 1819 on, the Pacific became a favorite cruising ground, many ships going as far as the coast of Japan. The commanders of these ships were men not only of great daring but also of a high degree of intelligence. A large part of what was then known of the ocean currents was due to the keen perception and accurate reports of these men. Their log-books and those of our merchant ships in the China trade were the chief and almost the only source of knowledge from which reliable information could be obtained by the masters, bound for the first time to ports or waters then unknown to them. A typical example of a descriptive page from a log-book has been reproduced and faces the opposite page. The first knowledge of hundreds of islands in the Pacific Ocean first came from the whale-men, and their contribution to the exploration and discoveries in the far North is too well understood to require eulogy.

To the dangers of navigation in little known or badly charted seas was added the very real danger from conflicts with the natives of the newly discovered or unsettled lands and islands. That many commanders and their men were not always gentle or just in their dealings with these natives is undoubtedly the fact, although through fair dealings and intelligent barter much lucrative trade was established. Bad treatment of natives by the crew of one ship often brought reprisals on the head of some innocent and well-meaning master who had the misfortune to be the next one to enter with his ship into the disaffected port.

Statistics have no real place in this paper, but it is interesting to note the activity of the whale-fisheries from 1820, when there had been more than full recovery from the War of 1812, to the beginning of the Civil War, as the number of the ships and the ports from which they sailed are a measure of the changes which were taking place in the various communities affected. The figures given represent not the number of ships owned in the places stated, but the number of ships which sailed from the ports named in the year given.

The Nantucket figures include a few ships from Edgartown, and with New Bedford is included those owned in Fairhaven and other towns in the immediate vicinity.

| Place | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

New Bedford, etc. |

43 |

80 |

97 |

115 |

96 |

|

Nantucket, etc. |

47 |

23 |

25 |

15 |

8 |

|

Cape Cod |

8 |

5 |

23 |

27 |

18 |

|

New London |

3 |

15 |

23 |

19 |

9 |

|

Long Island |

8 |

10 |

22 |

9 |

2 |

|

Rhode Island |

2 |

10 |

24 |

4 |

1 |

|

Other Conn. & Mass. ports |

5 |

2 |

20 |

13 |

11 |

|

New York ports |

8 |

3 |

1 |

|

|

|

124 |

148 |

235 |

202 |

145 |

An inspection of the records of these sailings shows that almost without exception the vessels were commanded by men with American colonial names, the descendants of the earliest settlers and the forebears of a now widely distributed Yankee stock. If one should to-day strike out of any southeastern Massachusetts or Cape Cod telephone directory the names which represent the Portuguese, French-Canadian and Irish invasion of recent years, there would be left a list which would closely resemble the page after page of masters taken from the maritime registers covering the first three-quarters of the last century: Allens, Chases, Coffins, Cooks, Davises, Delanos, Folgers, Husseys, Russells, Snows, Swains, Wings, — the list is too long to go further. Year by year the crews were more and more diluted with dark-skinned Western Islanders and in due course, as was natural, the better of these men who made good sailors became mates and finally masters, until now a large part of the small business of whaling from the Atlantic sea-ports is done in small vessels by and under command of the American descendants of these Portuguese Islanders.

The Civil War found the whale-fisheries, as had the earlier wars, quite unprepared to deal with the new dangers and problems. Ships were in various oceans, many in the Pacific, and out on long voyages of several years’ expected duration. The very distance off gave those in the Pacific a greater degree of protection from rebel privateers at the beginning of the war than had those in the Atlantic. Privateers or letters-of-marque were not difficult to equip for a service involving short voyages, and even converted tug-boats were employed by the Rebels. The records of some of the encounters between whale-ships and these armed privateers are a mixed story of misfortune, gallantry, and occasional inexcusable cruelty.

One incident in the career of the notorious Alabama is suggestive of the German procedure in the late war. One whale-ship, the Ocean Rover of Mattapoisett, having been captured, was at nightfall set on fire; other vessels of the whaling fleet attracted by the reddened sky hurried to her assistance and fell victims to the marauder. Among the ships thus destroyed were the Benjamin Tucker, Osceola, Virginia, and Elisha Dunbar of New Bedford and four others from Cape Cod and Connecticut ports. In June, 1865, the rebel privateer Shenandoah captured and burned in one day five whale-ships in Behring’s Straits. On the next day but one, while a portion of the whaling fleet had gone to the assistance of the Brunswick of New Bedford, which was jammed in the ice, the Shenandoah bore down on them and destroyed nine vessels. It was in this engagement that Captain Thomas G. Young of the Fairhaven barque Favorite showed exceptional gallantry and would have made an entirely useless sacrifice of his own life and that of his crew but for the forcible interference of his own men. Captain Ebenezer F. Nye of the Abigail of New Bedford also showed that courage and quickness which we have learned to associate with these old whaling masters. When he saw his ship about to fall into the hands of the Shenandoah, he quietly slipped away with two fully manned boats, and warned as many as he could of the rest of the fleet. In all the Shenandoah captured some forty vessels, most of which were destroyed. A few of the Pacific fleet escaped by going under the Hawaiian flag, but in both oceans the losses were great. Many were sold to enter other and less hazardous service and forty were bought by the Federal Government and made up the greater portion of the well-known “stone fleets” which were sunk at the entrances of the harbors of Savannah and Charleston to the end that the blockade of these ports might be made effective.

A glance at the faces of the men shown in a photograph of a group of the New Bedford masters of the ships which made up the “stone fleet” makes one realize the quality of the men who in those days carried the name and flag of the United States into all seas.118

The troubles of the whalemen did not end with the surrender of Lee and the ending of the war. In the autumn of 1871 thirty-four vessels were crushed in the ice off Point Belcher in the Arctic Ocean. This disaster, and the growing use of petroleum oils, discouraged the further development of the North Pacific whale-fisheries. In 1852 there had been 278 ships in the North Pacific with a reported catch of 373,000 barrels, the largest ever made in these waters in one season. In the three years prior to the Civil War, the number of vessels in the North Pacific was about 170 with an average catch of 100,000 barrels; but in 1876 the number of ships had dropped to eight and the catch to 5,250 barrels. The great days of the whale-fisheries were over; the strong ships and the stronger men who had manned them became an incident, but an important incident, in the history of New England and the United States.

Whale oil is still an important lubricant and the fisheries will, it is safe to assume, never be wholly abandoned; but the pursuit of the whale by a steam-driven vessel in the North Pacific and the use of whale guns, or the rare and short voyages of sad-looking schooners, manned by Portuguese Western Islanders in the Atlantic, have little in common with the earlier voyages.

A few words in closing as to the influence of the whale-fisheries on discoveries and trade. To the limits of the navigable seas the whale-ships were in general the pioneers. More often than not they were followed, rather than preceded, by properly equipped exploring expeditions. Into fields opened by venturesome whalemen followed the trade of both the North American States and England. But for the Pacific whalers, Australia and New Zealand would have waited years for their development. To the north the whalers were almost the only explorers of the Arctic Ocean and many lives were lost in the search for the North West Passage which would permit egress from the Arctic into either ocean. The whale-ships were, too, the school in which were reared the best and bravest seamen for the navy and merchant ships. Perhaps it is not too much to say that the qualities of courage, resourcefulness and determination learned at sea have given to the descendants of these merchant and whaleship masters the qualities which have enabled New England to hold its industrial leadership.

Mr. Arthur Lord spoke as follows:

In my introduction to the Plymouth Church Records, some reference is made to the resignation of the Rev. John Cotton as minister of the First Church and his dismissal by the church at his request on October 5, 1697.119 Some more serious reasons for this action by Mr. Cotton and the church than any differences in dogma or church polity are given by Judge Sewall in his Diary.120 It is difficult to reconcile the grave charges made by Judge Sewall with the fact that Mr. Cotton remained in Plymouth for a year after his resignation and made up his differences with the Plymouth Church, as his grandson, John Cotton,121 states, and then accepted a call to the Church at Charleston, South Carolina, receiving a recommendation from several ministers. Mr. Cotton died at Charleston September 18, 1699, and the Plymouth Church erected a monument to his memory on Burial Hill in Plymouth.

I was interested to find in a recently printed letter from Thomas Coram written from Liverpool, September 23, 1735, to the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Colman of Boston, an indignant and explicit denial of these charges against Mr. Cotton. Thomas Coram was born in 1667 or 1668 at Lyme Regis, Dorsetshire, and died in 1751. He was a shipbuilder in Taunton (Massachusetts) in 1694 and became a merchant in London in 1720. He is remembered now as the founder of the Foundling Hospital in London for “the reception, maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children.” His statue stands on the gates leading into the wide-open space in front of the hospital and his portrait, painted by Hogarth in 1740, is preserved in the interesting collection of pictures for the most part presented to the hospital by the artists. Thackeray wrote his Paris Sketch Book at No. 13 Great Coram Street.

That part of Mr. Coram’s letter material to this inquiry reads as follows:

I have also a letter from Mr. Josiah Cotton122 of Providence in New England thanking me for one of the Erasmus Ecclisiasticks (if I spel it right) I had no acquaintance with any of that name in New England I pray to know from you if he be a Desendant from that mr. Cotton a minister in Plymouth Colony and was, I think, an unkle to mr. Cotton Mather son of mr. Increase Mather of North Boston, who was in or about the year 1697 or within a year or two after Charged with attempting to be too Familiar with one of his Church Members Wife for which mr. Stoughton then Lt. Governor Displaced him from his Church w’ch Drove him to Carolina where he Dyed. I happened then to be building ships at Taunton in Plymouth Colony and well understood from those who had no friendship for that mr. Cotton, That all that affair was a Base piece of villainy that the man was no more Guilty of that Crime Charged on him than you or I was; I happened to speak of it severall Times in Plymouth Colony and in Boston, but at that Time it was looked on a Sort of Blasphemy to Suspect mr. Stoughton could do any thing Wrong beside I did not think fit to give my self much Trouble about it having no manner of Knowledge or acquaintance w’th that Cotton nor with his Nephew Cotton Mather with whome I never to my Knowledge Exchanged a Word with him in my life yet he (after the Example of a Snorting vile Fellow of Bristol County) spoke many fals and Injuring things of me to Cloath me in a Bares Skin which Hallow’d all the Hellhounds in Town and Country on to Wurry me. as I never wanted Resentment so I gave my self no paines about Mr. Cotton Mathers Unkle, and if I had, it would have had no Effect for the Generality of the People were taught to beleive I was a vile fellow an Enemy to Gods People and aboundance of such Kind of Cant and Diabolical practices however I beleive that man Mr. Cotton has as much Injustice done him in that abominable Proceeding against him as those other Innocent men who were Murdered on account of the Pretended Witchcraft and that there is equal Justice due to the Children and Posterity if any, of the one as the other If you or any want further explanation I shall not faile of sending it.123

More than two centuries have passed since this incident in the history of the First Church at Plymouth. It has little importance or interest to-day, but it seems to me desirable in order to complete the record that some reference to this letter from Mr. Coram, which is persuasive if not conclusive as to the injustice of the charges by Sewall against Mr. Cotton, should be noted in the Transactions of this Society which has published the records of the church of which Mr. Cotton was a minister and which contains some reference to this incident in Mr. Cotton’s life.

Mr. William O. Sawtelle, a Corresponding Member, exhibited several articles from his Islesford Collection relating to the Island of Mount Desert. The object of that collection he declared to be “A memorial to the pioneers of Mount Desert; a repository wherein may be lodged material of historical, genealogical, and antiquarian interest relating to the exploration, settlement, and development of the ancient territory of Sagadahoc, now Eastern Maine; an organized movement to rescue and to hold the vanishing evidence pertaining to the history of the town of Mount Desert and the areas included within that town by act of incorporation, 1789; and to provide for the perpetual care of any and all such material now in said repository or that may be acquired in the future.”

He then described the collection in detail:

From nothing in 1919, to proportions quite extensive, the Islesford Collection has now expanded until the entire lower floor of the building occupied has become very crowded and much of interest cannot be properly shown.

Though the primary purpose is to emphasize as far as possible everything relating to the history of the Mount Desert region, sight has not been lost of those who were active in the discovery, exploration, and settlement of the North American Continent; and old prints, many of them Houbrakens, of Drake, Ralegh, Henry Prince of Wales, patron of the Virginia Company, a complete set of the English sovereigns from Elizabeth to George III, portraits of Henry IV, Marie de Médicis, Louis XIII, Louis XIV, together with numerous original documents, autographed by some of these different rulers, here find place in the Colonial Room.

Among the most interesting of the original deeds of the Mount Desert region, all discovered tucked away in lofts and old chests, are two Cadillac-de Gregoire deeds, signed by Marie Thérèse de la Mothe Cadillac, one to Benjamin Spurling for one hundred acres of land on Great Cranberry, the other to John Stanley for the same amount on Little Cranberry Isle; the original deed from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to Daniel Gott for Little Placentia, now Gott’s Island, of date 1789, the earliest deed that has so far been found; also a Gott deed from John Quincy Adams and Ward Nicholas Boylston, signed by their agent, Salem Towne. The Cadillac-de Gregoire deeds were executed before Paul Dudley Sargent, son of Epes Sargent of Gloucester.

In the Mount Desert Room are many maps of the region — originals, in facsimile, and in photostat; the Sargent Collection, grouped about a large oil painting of Sargent’s Mountain, named for Stephen Sargent of Gloucester, a Mount Desert pioneer, containing much relating to Paul Dudley Sargent, photostats of his commissions, portraits of members of his family and of his Gloucester relatives; and the William Bingham Collection, containing copies of family portraits and material relating to his extensive eastern Maine purchase, with portraits of his son-in-law, Lord Ashburton, and his land agents, General David Cobb and Colonel John Black.

The Mount Desert Room also contains many photostats of surveys of the region, the most interesting of which are complete copies of the field notes of Sir Francis Bernard’s two surveyors, John Jones and Barachias Mason, who ran their Mount Desert lines in 1763–1765. These particular surveys served as the basis of the map of the Mount Desert region published in the coast charts of the British Admiralty in 1776.1124 Among the original autographs in this room are those of Bernard, Hutchinson, members of the Governor’s Council, selectmen of Boston, 1760, which includes signatures of several gentlemen who had to do with Bernard’s Grant of Mount Desert.

The Sir Francis Bernard Collection consists mainly of portraits of himself: the Club of Odd Volumes portrait, engraved by Wilcox, the first publication of the Club, also a copy of the edition that was offered for sale; the Colonial Society’s portrait, three copies, artist’s proof, one illustrating Mr. Albert Matthews’s Portraits of Sir Francis Bernard, a recent publication of the Club of Odd Volumes, and the portrait appearing in the Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts.125 A photograph of the family portrait of Sir John Bernard, son of Sir Francis, has recently been received with the compliments of Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Tyringham Higgins Bernard, who at present occupies the old house, Nether Winchendon Priory, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, to which Sir Francis retired after being driven from Boston.126

Of the contents of the two rooms devoted to the Cranberry Isles, no real description can be given; for here is shown material in which may be read the history of the five pioneer families — Bunker, Gilley, Hadlock, Spurling and Stanley, to the hearty coöperation and active interest of whose descendants the Islesford Collection owes its existence.

Mr. Sawtelle concluded his informal talk by announcing the discovery of an important document for which officials of libraries and historical societies in Philadelphia, Harrisburg, Washington and elsewhere, including Georges Bertin, who came over from France about 1895, had been searching for many years. This was the oath of allegiance to Pennsylvania and to the United States taken May 19, 1794, before Matthew Clarkson, Mayor of Philadelphia, by Charles Maurice, Prince de Talleyrand-Perigord. It seems probable that the original was signed in duplicate — one copy for the authorities of Pennsylvania, the other for those of the United States. At all events, a copy with Talleyrand’s autograph has just been found by Mr. Julius H. Tuttle in the Pickering Papers at the Massachusetts Historical Society. In 1794 Timothy Pickering was Postmaster General and in 1795 became Secretary of State, which position he held until 1800. Presumably it was in his official capacity that he acquired the document in question, which reads as follows:

I Charles Maurice de Talleyrand Perigord formerly Administrator of the Department of Paris, son of Joseph Daniel de Talleyrand Perigord a general in the armies of France, born at Paris and arrived at Philadelphia from London do swear that I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and to the United States of America, and that I will not at any time wilfully and knowingly do any matter or thing prejudicial to the freedom or independance thereof

Ch Mau De Talleyrand-Perigord

Sworn the 19th May 1794

Before

Matth Clarkson

Mayor127

Mr. George P. Winship exhibited the first record book kept by the clerk of “The New England Company,” otherwise “The Corporation for Propagating the Gospel in New England,” with entries dated from 1656 to 1686,128 and spoke as follows in regard to the relation between this Company and the missionary work of John Eliot the Apostle:

On March 17, 1660, the clerk recorded that the members present at a meeting approved of a proposal to print a manuscript sent over for this purpose by Eliot, “And that 1500 bee printed by Mrs. Symones, or such others as shall print the said bookes cheaper, and that the same bee referrd to Col. Puckle to take care heerof.” A week later Colonel Puckle reported that “hee hath agreed with Mr. Maycoke a printer to print ye Indianes Confessions at a farthinge per sheet, and that hee hath bought 20 reames of Paper at 3s 10d per reame.”

Fortunately, the Treasurer’s ledger, containing the accounts of the Company for the decade from 1650 to 1660, is still in existence, and makes it possible to state what this pamphlet, the next to the last of the series of “Eliot Indian Tracts,” actually cost, and also to draw some inferences as to the success of Colonel Puckle’s effort to reduce the cost of printing. These accounts show that the tract of 1655, “A Late and Further Manifestation of the Progress of the Gospel amongst the Indians in New-England.… London; Printed by M. S. 1655,” cost £12.14.00 for printing and paper; and £7.12.00 for sewing and covering in “blew & Marble paper.” As 3000 copies were printed of this 32 page pamphlet, the cost per copy was about a penny apiece for printing and paper, or very nearly a farthing a sheet, and rather more than a half-pence each for binding.

The 1659 tract, “A further Accompt of the Progresse of the Gospel amongst the Indians, … declaring a purpose of Printing the Scripture in the Indian Tongue … London, Printed by M. Simmons for the Corporation of New-England, 1659,” cost £24, Mrs. Simmons providing the binding as well as paper and printing. This amounts to nearly two pence each for the 3000 copies. As this tract consisted of 48 pages, the proportional cost figures out at considerably less than that of its immediate predecessor.

In 1660, Colonel Puckle bought the paper and paid for the binding, leaving only the type-setting and press-work to the printer. Macock was paid £8.12.06 for 1500 copies of the 88 page “A further Account of the progress of the Gospel … being A Relation of the Confessions made by several Indians. Sent over to the Corporation … by Mr. John Elliot. London, Printed by John Macock. 1660.” This makes 8280 farthings, and the 1500 copies called for 16,500 sheets, so that Macock received just half what he should have been paid according to the entry of Colonel Puckle’s agreement with him. An analysis of the prices paid in 1655 and 1659 shows that half a farthing a sheet would have been approximately what Mrs. Simmons received for this part of the work; and the probability is that the clerk made a mistake in his entry.

Thirty-five reams of paper were purchased for £6.14.02. This was two reams more than the 1500 copies called for, but some of this extra paper would have necessarily been used in the normal wastage and over-run of the presses. Whatever was left became a part of the perquisites of the printer.

The binding cost £4.05.00, but as the blue paper wrappers were omitted, undoubtedly as part of the cheapening process, this figure cannot be compared with that of 1655, with any satisfactory result.

A comparison of Macock’s pamphlet with the two printed by Mrs. Simmons shows that he reduced the number of words on each page, by wider spacing, so that he made the manuscript fill nearly an extra sheet. He also spread out the headings and took advantage of opportunities to leave blank spaces at the foot of pages, so that he was able to charge for at least another half sheet. He also omitted side notes and in other ways kept his costs down wherever possible. Taking all these factors into account, the actual cost of this 1660 tract to the Society was apparently about fifteen percent more than it would have been if Colonel Puckle had not undertaken to get it done more cheaply.

The Corresponding Secretary reported that letters had been received from Mr. Alfred Marston Tozzer, accepting Resident Membership; and from Mr. William Davis Patterson and Mr. Kenneth Charles Morton Sills, accepting Corresponding Membership.

The President appointed the following Committees in anticipation of the Annual Meeting:

To nominate candidates for the several offices, — Dr. Charles Lemuel Nichols and Messrs. Henry Winchester Cunningham and Francis Tiffany Bowles.

To examine the Treasurer’s Accounts, — Messrs. Harold Murdock and Frank Brewer Bemis.