FEBRUARY MEETING, 1930

A Stated Meeting of the Society was held at the invitation of the President, at No. 44 Brimmer Street, Boston, on Thursday, February 27, 1930, at three o’clock in the afternoon, the President, Samuel Eliot Morison, in the chair.

The Records of the last Stated Meeting were read and approved.

The Corresponding Secretary reported that letters had been received from Mr. James Rowland Angell, Mr. Thomas Stearns Eliot, and Mr. George Andrews Moriarty, Jr., accepting Corresponding Membership; and from Mr. Michael Joseph Canavan and Mr. Fulmer Mood, accepting Associate Membership.

Mr. Grenville Lindall Winthrop of Lenox was elected a Resident Member, and Mr. Earl Morse Wilbur, of Berkeley, California, was elected a Corresponding Member.

Mr. Michael J. Canavan spoke on:

ISAAC JOHNSON, ESQUIRE, THE FOUNDER OF BOSTON

Isaac Johnson was born in 1601 in Stamford, Lincolnshire. He owned estates in four counties and had a town house in Boston, Lincolnshire. In 1623 he married the Lady Arbella Fiennes-Clinton, sister of Theophilus, fourth Earl of Lincoln.434 He was a devout Puritan, one of the little group which, in 1627, “being together in Lincolnshire” fell into discourse about New England and the planting of the Gospel there, and imparted their thoughts “by letters and messages, to some in London and the west country.” In the year 1629 they procured a charter.435

According to Thomas Dudley Mr. Johnson was one of the trading company of 1628, the members of which becoming dissatisfied at having the control in London paid two thousand pounds to acquire a Royal Patent without the clause which restricted the government to London.436 Isaac Johnson was one of the grantees of this patent.437 He probably helped to compose the “General Considerations for Planting New England,” which recommended that godly persons who “live in wealth and prosperity” should go over “and runne in hazard with them of hard and meane condition,” and that they should brave hunger and the sword and trust in God’s providence. It declared that the best is required in great things, and that the main end was the propagation of religion.438

This pamphlet probably drew John Winthrop and his son into the company in the summer of 1629.439 Heart and soul Johnson was for this project. As he often said to Winthrop and Downing, he was in the business “to spend and be spent.”440 In July, 1629, he had Winthrop and Downing come to the magnificent residence of the Earl of Lincoln at Sempringham, to consult with him and others. On August 26, at Cambridge, Sir Richard Saltonstall, Thomas Dudley, Isaac Johnson, John Winthrop, and seven more, agreed to embark with such of their families as were to go, by March 1, “to inhabit and continue in New-England: Provided always, that before the last of September next, the whole Government, together with the patent . . . be first, by an order of Court, legally transferred” to New England.441 On August 29 the General Court approved this.442

Mr. Winthrop made his first appearance at the General Court on October 15, and on October 20 was elected Governor.

All were hard at work collecting arms and other supplies. On December 17 Johnson wrote a letter to the Governor, who had chided him for his too great modesty: “Pray for mee the more, and expect the less . . . what I am I a[m] . . . mee thincks I ended soe abruptly with my paper without expression of loue & affection answerable to the receipt of yours. But I am weary & not very well, therefore entreat you to supply it out of the abundance of yours.”443

On March 29 they sailed in the Arbella, so named in honor of Johnson’s wife, and after a long, tempestuous voyage, landed on these inhospitable shores, with many sick of scurvy and half their cattle dead. At Salem, instead of the fields of grain and the happy plantation they had been led to expect, they found dearth, sickness, and starvation two weeks off. Many servants had been sent over, but eighty of them had died and the rest had been sick, mutinous, and lazy. About one hundred persons were sent back to England, for they had not food enough for themselves. Johnson had sent to New England many servants, among them skilled workmen, and undoubtedly a house had been built for the Lady Arbella.444

“Salem pleased them not.”445 On June 17 the leaders went by sea to inspect Charlestown, and returned. About July 10 the leaders and people moved to Charlestown. “The Lady Arrabella and some other godly Women aboad at Salem, but their Husbands continued at Charles Town.”446

There was much to be done at Salem, sorting out the good servants from the bad and arranging for their passage to England. Johnson was there on July 25, for on the next day Dr. Samuel Fuller wrote to Governor Bradford that he had met him the night before and that he had received from Governor Winthrop notice that a fast would be held at Charlestown on July 30 and a church formed on the same day. Accordingly Governor Winthrop, Deputy Governor Dudley, Isaac Johnson, and the Reverend John Wilson entered into a covenant and laid the foundation of the church both at Charlestown and Boston.447

The Governor and grandees lived in the “Great House” which had been erected for them the year before by Thomas Graves, but the poor people were in huts and tents, so sick with the hot fever that they could not properly attend to each other. Many died. The disease was attributed to a lack of running water.448

Mr. Blackstone, coming over from Shawmut “acquainted the Governor of an excellent spring there, withal inviting and soliciting him thither.”449 Blackstone was the son of a minister at Horncastle, Lincolnshire, and had attended there a school founded by the first Earl of Lincoln. Thence he went to Emmanuel College, where he held a scholarship given by the same Earl. Isaac Johnson also attended Emmanuel. Both took the degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1618. Then they went to Peterborough and both were made deacon and priest, Blackstone in 1619 and Johnson in 1620. They took their degrees as Masters of Arts at Emmanuel in 1621.450

Although he was a little older, Blackstone must have looked up to Isaac, who was the grandson of the great Dr. Chaderton, Master of Emmanuel, and also a grandson of Robert Johnson, Archdeacon of Leicester, Rector of North Luffenham, Canon of Windsor and of Norfolk, and Prebend of Peterborough, who had founded two hospitals in Rutland and two schools. He was also supporting half a dozen minor institutions in the same county, and had founded sixteen exhibitions, a kind of scholarship at the universities, four of them at Emmanuel College.451

Johnson’s marriage to the Lady Arbella in 1623 connected him with the family which had given Blackstone his education.452

Blackstone went to Massachusetts Bay with Robert Gorges in 1623 and was left at Shawmut as his agent. On Robert’s death, about 1628, he became agent of his brother, John Gorges, who had married the Lady Arbella’s sister.

Since they had been students together for about ten years, the meeting between Johnson and Blackstone must have been a pleasant reunion. There must have been many inquiries about the Lady Arbella and news that she was living in Salem among sick and mutinous servants and could not be brought to Charlestown, which was now more dangerous than Salem, because of the fever and the lack of running water.

It seems probable that Blackstone at once asked Johnson, and perhaps Coddington of Boston, another assistant, to come to Shawmut where there was an abundance of springs, and showed him his cottage on the southeast slope of Trimountain, where there were several springs, as well as the pleasant slope on the east side with what was later known as the Cotton Spring at the head of it and another great spring where the lower part of the Quincy House now is. This one was made a source of supply for the houses at the head of the cove by a company in 1652.453 Coddington had a brick house completely built at Shawmut before September 7.454 Blackstone would naturally have taken him and Johnson over early — when the cry for running water arose, or before. As Johnson was the great man on whom they relied, he probably led them across the river to the springs and started his house, but Coddington was not so much oppressed by business and could push the work more. Moreover his wife died by August 2, and if he had not had the work well started before her death, it is probable that he would not have built.455

Johnson was one of the unfortunate “undertakers,” whose business it was to provide money.456 With Sir Richard Saltonstall, John Winthrop, and Thomas Dudley, he was straining his credit to the utmost to enable Captain Pierce to get provisions and to pay freight. As Johnson had the longest purse much was expected of him, and after his death his estate was embarrassed by debts incurred in America.457

Much building was going on in Trimountain in August and such high wages were demanded that the Court of Assistants on August 23 forbade carpenters, joiners, bricklayers, sawyers, and thatchers receiving more than two shillings a day. At the same meeting it was ordered that the next meeting should be held at the Governor’s house in Charlestown on September 7. If Winthrop’s house was so far along, and Coddington’s finished before the name was given to Boston, we should expect Johnson to show equal desire to establish his good lady in a good house with running water, among pleasant society. The Governor’s house was started on August 2. At the meeting of the Assistants on August 23, justices of the peace were appointed. They were the Governor and the Deputy Governor, for the time being, and Sir Richard Saltonstall, Mr. Johnson, Mr. Endicott, and Mr. Ludlow. Johnson was not at this meeting, and, since his wife died before the end of the month, he was undoubtedly with her at Salem.458

On September 7 it was ordered that Trimountain should be called Boston; Mattapan, Dorchester; and the town upon the Charles, “Waterton.” The language intimates that Boston was already a settled town. By the order of August 23 Sir Richard Saltonstall was to be justice at Watertown, Endicott at Salem, Ludlow at Dorchester, and Johnson at Trimountain across the river. He must have been building or have had a house at Boston already, or Coddington would have been appointed justice there.

Johnson was at the meeting of September 7, and wrote letters about the twelfth. Answers which are in the Winthrop Papers show that he was overcome by grief, broken down by the death of his wife.459 Winthrop must have been a great comfort to him, for the Governor’s affectionate nature would have made him sympathize, and he was not afraid to express his feelings.

Johnson sat with Winthrop at an inquest in Charlestown on September 18, but he was not at the Court of Assistants on September 28 when a tax was levied for the support of Mr. Patrick and Mr. Underhill. It was laid in the proportion of £11 for Boston and £7 for Charlestown, showing that Boston had already outstripped Charlestown.

On September 30 Winthrop recorded in his journal: “About two in the morning, Mr. Isaac Johnson died; his wife, the Lady Arbella . . . being dead about one month before. He was a holy man and wise, and died in sweet peace, leaving some part of his substance to the colony.”460 Cotton Mather wrote that the Lady Arbella “left an earthly paradise . . . to encounter the sorrows of a wilderness . . . and then immediately left that wilderness for the Heavenly paradise,” and applied to her husband Sir Henry Wotton’s epitaph on two lovers:

“. . . . . . . . He try’d

To Live without her, lik’d it not, and Dy’d”.461

In the first part of the eighteenth century it was a general tradition in Boston that Mr. Johnson led the settlers over from Charlestown to Boston and had the lot between School and Court Streets, that his house was on the northern part of this land, where the City Hall Annex now stands, and that at his own request he was buried in the southwestern portion of his lot. To make sure that this was true, that careful historian Thomas Prince consulted the man whom he considered to be the best authority, Chief Justice Samuel Sewall, who informed him:

That this Mr. Johnson was the principal cause of settling the town of Boston, and so of its becoming the metropolis, and had removed hither; had chosen for his lot the great square lying between Cornhill on the southeast; Tremont-Street on the northwest, Queen-Street on the northeast; and School-Street on the southwest; and on his deathbed desiring to be buried at the upper end of his lot, in faith of his rising in it. He was accordingly buried there; which gave occasion for the first burying place of this town to be laid out round about his grave.462

Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who was born in 1711, says in his History of Massachusetts that many materials for a history of the colony came to him from ancestors, “who for four successive generations had been principal actors in public affairs.”463 In 1639 William and Anne Hutchinson had the southern corner of the Johnson lot. In England they had been, with Johnson, attendants at John Cotton’s church at Boston, Lincolnshire. Thomas Hutchinson tells of a will made by Johnson on April 28, 1629, which values his interest in the New England adventure at £600. That was just a beginning. Abraham Johnson, father of Isaac, said in 1638 that his son had spent £5000 in New England.464 Hutchinson also says that Johnson

was buried, at his own request, in part of the ground upon Trimontain or Boston, which he had chosen for his lot, the square between School-street and Queen-street. He may be said to have been the idol of the people, for they ordered their bodies as they died to be buried round him, and this was the reason of appropriating for a place of burial what is now called the old burying-place, adjoining to King’s chapel.465

Abiel Holmes, in his American Annals; Snow, in his History of Boston; Budington, in his History of the First Church in Charlestown; Young, in his Chronicles of Massachusetts Bay — in short, all the historians — accepted these accounts. A girls’ school was named the Johnson School, and the old City Hall was Johnson Hall. Everyone followed Sewall, and Samuel G. Drake in his History of Boston, published in 1856, said that some memorial ought to be erected to Johnson.466

Drake and James Savage were noted antiquarians in the middle of the nineteenth century. They hated each other.

Savage was an old man who had devoted a good part of his life to deciphering John Winthrop’s journal or “History of New England,” and produced editions of it in 1826 and 1853. He was president of the Massachusetts Historical Society and, like Dr. Samuel Johnson in his club, he ruled the roost. To friends, especially if they agreed with him, he was genial and delightful. Yet he was a good hater, intense in his likes and dislikes, and not chary of expressing them. He resented opposition even from his associates; and his friends gave way to him from policy. Wise members of the Society held their tongues; the small fry agreed with him. He reverenced John Winthrop as a god. To Winthrop alone belonged the spotlight. No others must come near it. All the honor must be his.

Drake kept an antiquarian bookshop. He was president of the New England Historic and Genealogical Society, a careful investigator, and the author of that mine of information, the History and Antiquities of Boston.

In 1853 he criticized Savage’s second edition of Winthrop, especially for the invidious character of his notes. He pointed out that in the 1826 edition Savage wrote of Johnson as “this gentleman who is usually regarded as the founder of Boston.” In the 1853 edition it is “formerly regarded as the founder of Boston, where it is not probable that he ever passed a single night.” No reason for the change was given. The statements of Prince and Hutchinson, Drake declared, should not be discredited “by a single dash of any modern pen.”467

In his Genealogical Dictionary of New England Savage had an article on “Isaac Johnson of Salem.” He said that the Lady Arbella died a few weeks after landing at Salem, and was buried there, and that her husband followed her a month later, probably to the same spot, before the settlement of Boston. “A splendid myth as to his place of burial has possession of the common credulity,” Savage declares, and he says that though Prince gave the traditional account from Sewall, no earlier authority ever alluded to it. Sewall was not born for nearly twenty-two years after the event, Savage continued, and did not come here from England for nine years more, so that the probability is that the tradition is worthless, and that after the death of Johnson, September 30, 1630, before even the meanest cottage could be built in Boston since the coming of the Puritans and before Winthrop or Wilson had crossed from Charlestown where Johnson died, the corpse was either buried there or if removed at all, was transported by water to Salem to be laid beside his noble partner. He left no children and as his wife was too ill to leave Salem, no doubt he accompanied her. If he never lodged out of the place of first landing, unless it might be for a single night before or after the magistrates’ August court, all weight of probability is in favor of Salem rather than Boston as his place of burial. Drake’s opposite opinion, Savage said, seems to rely solely on Sewall, who was a child when first brought from England more than thirty years after the death of Johnson, in whose honor the tradition was gradually elaborated and perpetuated by the credulity, not the judgment, of Prince.468 Savage adds that the approximate situation of the burial place of the Lady Arbella and Isaac Johnson in Salem is known. In this he relies on the statement which Dr. Holyoke gave to Abiel Holmes and J. B. Felt about 1825 as to Lady Arbella’s grave, but he rejects Sewall’s account of a century earlier.469 There was no tradition in Salem that Johnson was buried there. There was, however, a family record of the Winthrops in 1742 that Isaac Johnson and the Lady Arbella “lie both buried in the vault of the Winthrops at Boston.”470 I construe this to indicate that at the time of building King’s Chapel or its enlargement, the remains of Isaac and a woman interred near him were transferred to the Winthrop tomb. That southwest portion of his lot was an uneasy place for a grave.

As to no house being in Boston at the time of Johnson’s death, Coddington’s Declaration of True Love was written in 1672, and in it it is said that Coddington built the house in which Governor Bellingham was then living, before the town received the name of Boston.

The town records begin in 1634. The registry of deeds goes back to between 1640 and 1650; but, fortunately, Lechford, the lawyer, entered in his notebook in 1639 the sale of a house and what Coddington still had of his original lot. It was next to Bellingham’s. Brattle Street and Cornhill now run over it. It reached from the northeastern side of Trimount to the head of the Cove. The lots on Washington Street ran back to “Coddington’s swamp,” and there was a great spring on it, about on the site of the lower part of the Quincy House.471

The first item in Boston Births and Baptisms is: “1630. Town. Edward son of Wm and Elizabeth Aspinwall born 26 day of 7th month.”472 Mr. Aspinwall was prosperous and undoubtedly Mrs. Aspinwall had shelter.

Savage is loath to allow any settlement unless by Winthrop, but we have seen that the latter was to begin to occupy his Charlestown house about September 7, when the General Court was to meet in it.

In a cooler, wiser moment, however, Savage thought quite differently. In the second edition of Winthrop’s History he has a note on the time of the foundation of churches, and says: “In September, 1630, the greater part of the congregation lived on this [the Boston] side of the river.”473

If Savage’s theory that Johnson never lodged out of the place of first landing except for a single night before or after the August court, is correct, Johnson died in Salem; but a little earlier Savage said that he died in Charlestown.474 He cannot have it both ways, and neither is correct, for Johnson died in Boston. The particular night which Savage picked out for him to sleep in Charlestown is just the time when he was in Salem with a sick wife. He was not at the meeting on August 23, but was at the one on September 7. He was in Charlestown on July 30, and, according to Dr. Fuller, there on August 2, when he intended to visit Plymouth.475

There is no intimation that the Lady Arbella was sick before the latter part of August, when she died. She stayed in Salem because a house had been provided. We have seen that Johnson sat with Winthrop on an inquest on September 18, and was appointed a justice on August 23. The Governor and Deputy Governor were justices at Charlestown; Saltonstall at Watertown; Ludlow at Dorchester; and Johnson must have built or have been building a house in Boston or Coddington would have been appointed there. The order of September 7 that Trimountain be called Boston; Mattapan, Dorchester; and the town upon the Charles, “Waterton,” shows that Boston was already a town. We know from Winthrop that on June 17 the officials went by sea to Charlestown to inspect the place and moved there with the people about July 10 or 12.

In view of all this Savage’s note on Johnson is utter nonsense.

Toward the end of August, after his wife’s death, Johnson was in Charlestown or Boston. Can one imagine that from the time he left her in Salem he was not busy providing a good residence for her in a pleasant place where she would have the company of the gentry? Winthrop, Saltonstall, and Coddington were building in Boston. Johnson was the wealthiest, and had a wife used to the luxuries of life. She could not be left in Salem. They would all have been imbeciles to have stayed in Charlestown to die when the life-giving springs were only half a mile off. And, as Sewall said, Johnson led them over. There were three Lincolnshire men, for Johnson had a house in old Boston, Coddington lived there, and Blackstone was of Horncastle. The three occupied all the east and northeast slope of Trimountain. The lot of fifty acres later set off to Blackstone reached up to School Street; Coddington’s property was on the northeast slope from the Cove to Court Street, and Johnson’s was the rectangle between Court and School Streets.

Prince could have found no one who took a greater interest in funerals, tombs, graveyards, and first settlers, than Samuel Sewall. For more than twenty-five years he was an intimate friend of Simon Bradstreet, who had been in the service of the Earl of Lincoln, had known the Lady Arbella, and had come over in the ship with Johnson and served as an Assistant with him. Sewall and Bradstreet must have talked about the Johnsons. In 1684 they took the deposition of four men about the Blackstone deed to the town.476 One of them, Robert Walker, was a friend of Sewall’s father, and close to Sewall.477 Another, Francis Hudson, was one of the first of the newcomers to set foot on Shawmut.478 Sewall served as Assistant several years with William Hauthorne who came with Johnson in the Arbella, and he knew old Anne Pollard, who testified about Blackstone in 1711. He refers to dropping in at her tavern, made her will, read it to the heirs, and was a mourner at her funeral. Old Joshua Scottow and he worked together on the history of the South Church, and had prayer meetings at each other’s houses, when Scottow would prose away about the virtues of the founders, prisca fides, and about the old meeting house with its mud walls, thatched roof, and wooden chalices.479

Savage’s implication that Sewall lied to Prince seems unfounded, but Savage did not hesitate to make rash assertions when he wanted to make a point.

A bit of further evidence is a memorandum by Winthrop, December 7, 1630: “I had . . . of Mr. Johnson’s 9 cows, 2 at Boston.”480 As Johnson herded his cows at Swampscott and Nahant, these two would seem to have been kept in Boston for his use at home.

Johnson’s death was a great blow to the colony. The common people of England looked up with awe to the landowners, especially those with great connections, and it was terrible to lose this able, wise, devoted, wealthy man, who had been one of those who started the venture and contributed freely to the establishment of the colony. He had intended to sell his estates in England in order to invest the proceeds here.481 He and his wife lost their lives, but not before he had established a church of Christ in the wilderness and founded the little town of Boston. Out of small things came great results.

Dudley, in his letter to the Countess of Lincoln, says of Johnson: This gentleman was a prime man amongst us, having the best estate of any, zealous for religion, and the greatest furtherer of this Plantation. He made a most godly end, dying willingly, professing his life better spent in promoting this Plantation than it could have been any other way. He left to us a loss greater than the most conceived.482

Edward Johnson gives the general feeling:

The first beginning of this worke seemed very dolorous; First for the death of that worthy personage, Izaac Johnson Esq. whom the Lord had indued with many pretious gifts, insomuch that he was had in high esteeme among all the people of God, and as a chiefe Pillar to support this new erected building. He very much rejoyced at his death, that the Lord had been pleased to keepe his eyes open so long, as to see one Church of Christ gathered before his death, at whose departure there was not onely many weeping eyes, but some fainting hearts, fearing the fall of the present worke.483

Governor Winthrop had an old friend, William Pond, whose two sons he had helped to come to this country. One of them wrote from Watertown on March 15, 1631, thanking his father for some provisions he had received, and ends his letter in this way:

We do not know how longe theis plantatyon will stand, for sume of the magnautes that ded uphould it have turned off thare men and have givene it overe. Besides, God hath tacken away the chefeiste stud in the land, Mr Johnson & the ladye Arabella his wife, wiche was the cheifeste man of estate in the land & one that woold a don moste good.484

Isaac Johnson should not be forgotten. He was one of those who in 1627 started to plant the colony, and was one of the trading company of 1628. He was a grantee of the royal patent, and he and his wife came over and laid down their lives to promote the colony. Before his death he became one of the four founders of the first church, and led the sickly colonists over to the springs of running water in Boston.

A Tercentenary of Boston without Isaac Johnson would be like the play without Hamlet.

Mr. Samuel E. Morison read the following paper:

THE COURSE OF THE ARBELLA FROM CAPE SABLE TO SALEM

In a former volume of our Publications485 our late member Mr. Horace Everett Ware, one of those rare persons who combine historical knowledge with astronomy and practical navigation, traced the course of the Arbella across the Atlantic. The present paper is by way of a supplement: an attempt to make a more exact tracing of the latter end of the voyage from Cape Sable to Salem than was necessary for Mr. Ware’s purpose, and to settle the question of the Arbella’s first anchorage in American waters.

The data recorded in Winthrop’s Journal, which are our sole reliance for plotting the voyage, were doubtless obtained by him from Captain Peter Milborne, the master of the ship; for Winthrop had no knowledge of navigation. Winthrop mentions, on April 15, the Captain’s taking observations with the cross-staff, a rough-and-ready means of ascertaining latitude. Like every shipmaster of the time, he had no other means of determining longitude than by estimating the ship’s speed through the water. Presumably he corrected his time every noon when the sun was visible, so that the times given by Winthrop are substantially correct.

I find no evidence in the Journal of a published map or chart of the New England coast being on board; although it seems likely that the Captain possessed some seamen’s “cardes” of the Gulf of Maine, similar to the one of Cape Ann which Winthrop copied into his Journal. None of the names on Captain John Smith’s Map of New England, which appeared in 1616, are mentioned; nor does Winthrop use a single name from either of Champlain’s published maps of New France.486 If, however, Captain Milborne had no manuscript charts of the Gulf, there must have been someone aboard who had already visited the New England coast. Winthrop uses names such as Cape Porpoise, Boon Island, and the Isles of Shoals, which must have been given to these places by Englishmen some time previous to 1630, although they are not found on any map until long after.

THE COURSE OF THE ARBELLA ACROSS THE GULF OF MAINE

reproduced for the colonial society of massachusetts from a drawing by samuel c. clough

My plotting of the Arbella’s course cannot, with the materials available, approach the exactitude that could be obtained with a modern seaman’s log-book. Sailing vessels never sail an absolutely straight line, even when the wind is steady, and Winthrop does not note minor variations of the winds. Nor have I made any allowance for tidal currents. But I have reproduced all the available data in this article, so that anyone may do the work over again to his liking, if he disagrees with my interpretation of the material.487

For crossing the Gulf of Maine the Arbella had what fishermen would call a very fair chance.488 South-west winds prevented her from sailing straight across from Cape Sable, as her master evidently intended; but she had no foul weather, and but a few hours’ fog. Under the circumstances, Captain Milborne made the best course possible, losing no opportunity to make his westing, but keeping in touch with distant landmarks.

The Arbella took her departure from the Scilly Islands, together with her consorts the Jewel and the Ambrose, on April 11, 1630. She crossed the southern end of the Grand Banks of Newfoundland on May 26, separated from her consorts on June 2, and on the next day found bottom with her dipsey lead at eighty fathom. This point, according to Mr. Ware’s calculations, was well south of the site of Halifax, Nova Scotia. Fearing lest a due westerly course take him onto the Georges shoals, as indeed it would, Captain Milborne stood W. N. W. for Cape Sable. Bottom was found again at 2 p. m. on June 6. Shortly afterward the fog cleared, revealing land about five or six leagues (fifteen to eighteen nautical miles) to the northward. This must have been Cape Sable, Nova Scotia, as Winthrop supposed.489 Having made this landfall, they took a fresh departure on a W. by N. course, intending to make the New England coast at “Aquamenticus” (York, Maine) by sailing along latitude 43° 15′.

The night of June 6–7 was foggy, and the wind a light southerly. About four in the morning they sounded and found thirty fathom of water. Allowing for the run from off Cape Sable, and assuming that Winthrop had the latitude right, the sounding indicates a position of about 43° 15′ N., 66° 25′ W., a point about eighteen miles W. by S. of Seal Island, which they had passed in the night. As it was somewhat calm, says Winthrop, the Arbella hove to, codlines were baited, and in less than two hours they took “wth a fewe hooks 67: coddfysh, most of them verye great fysh, some 1 yd & ½ long, & a yd in compass.”490 This happy confirmation of the fish stories of Captain John Smith and earlier voyagers, doubtless encouraged the ship’s company, while affording means for a welcome change in the monotonous sea diet of salt meat and dry biscuit.

After this we filled our sayles, & stood W: & N:W: with a small gale. The weather was now verye colde: We sounded at 8: & had 50: fath. & being calm we heaved out hooks againe & took 26: codd, so we all feasted wth fysh [this] day.

A W. N. W. course from the former fishing grounds would have taken the Arbella in two hours’ sailing at five knots, to a fifty-fathom sounding on the edge of the German Bank. The bottom deepens off so rapidly here that this second fishing place can be located within a couple of miles.

Continuing the same course, at 1 p. m. there came up a fresh gale from the N. W. Winthrop’s accounts of winds and courses show that the Arbella could not sail closer than seven points to the wind, which was the best that any square-rigger could do until the clipper ship era. Hence with the wind N. W., she must have altered her course to N. E. by E. It was fortunate indeed that she had weathered Cape Sable; for the N. W. wind “failed soon” and at night a “styff gale” blew up from the W. by S., almost directly contrary to the Arbella’s intended course, and straight into the Bay of Fundy. Consequently Captain Milborne stood “to & againe, with small advantage.” That is, he tacked back and forth close-hauled, and made very little distance to windward. It must have been a rough night, especially when the ebb tide from the Bay of Fundy made down against the wind; but presumably by this time the Arbella’s company were proof against seasickness.

When morning broke on June 8 the wind was still in the same quarter, “W: & by S: faire weather but close and colde.” So the Arbella stretched a taut bowline with the port tacks aboard.

We stood N: N: W: with a stiff gale491, & about 3: in the afternoone had sight of lande to the N: W: about 15492 leagues, which we supposed was the Isles of Monhegan: but it proved Mount Mansell.493

Mount Mansell was a short-lived English name for the island which Champlain had discovered in 1604 and named Mount Desert.494 This island, with a range of hills running up to over fifteen hundred feet, is the most conspicuous landmark on the Atlantic Coast of the United States.495 Running a line southeasterly from Green (now absurdly renamed Cadillac) Mountain, the highest elevation on Mount Desert, for twelve leagues (thirty-six miles), brings us to a point at latitude 44° 2′, longitude 67° 28′. This I assume as the point where the Arbella sighted Mount Desert. It is difficult to estimate the distance of a hill arising from the sea, when you do not know its height. Winthrop variously estimates the distance of this landfall at eight, fifteen, and twelve leagues; but the last figure (as on legend II, below) appears to be his final estimate, and considering the distance that Mount Desert can be seen in clear weather, twelve leagues is more probably correct than anything less. That distance could easily have been reached by a speed of four or five knots after the beating to windward during the night.

From this point we have the aid of a page of Winthrop’s Journal which none of the previous editors of that important work have reproduced.496 It consists of a sketch map with legends, illustrating the Arbella’s course from her sighting Mount Desert on June 8 to sighting Agamenticus on June 10. The page is reproduced here, and I print all the legends in the order in which I think that they were written; and numbered with Roman numerals in order to facilitate reference, as we continue the course.497

In the lower left-hand corner, written across the page like the text of the Journal:

I

Tuesday June 8.

about 3: in the afternoone

the lande appeared thus to vs

in the Center of this circle

In the center of the page is the circle referred to, drawn with dividers, with the conventional fleur-de-lys to represent the north, rhumb lines drawn by rulers through the cardinal points, and also a N. W. and S. E. line on which is inscribed:

II

12: le[a]g[ues]:498

At the end of this line is a sketch of a two-peaked mountain, the easterly peak considerably higher than the westerly one, and over it is the inscription:

Winthrop Sketches of Points on the Coast of Maine

To the right of this sketch, and divided from it by a rough vertical line, is a sketch of a range of nine or ten mountains, three higher than the rest, with the legend:

IV

Thus it seemed next daye

this lyes in 44.

Dropping from the base-line of the highest mountain is a line drawn about S. by E. to a roughly drawn double circle around a dot, and bearing the legend:

V

10 [ ]: leg, N: b: W:499

At the upper left-hand corner of the page is the legend:

VI

when the great hill in the maine Lande

laye N: & b: E: from vs, the rock laye E by N.

& the 5: or 6: smale Ilandes of low land laye the

foremost N: & the rest more W: eache after other

& seemed to be middwaye towards the mayn

Between the longer range of mountains and the circle is a rough sketch of three islands, with something below that appears to be a rock erased, and below and to the right what appears to be a rough plan of a rock surrounded by waves. The legend, with first line above and other lines below the islands, reads:

VII

5. or 6. lowe ilandes lye ther

this rock lyes thus

a litle aboue water. neere no lande by 3: or 4: leg.

On the upper part of the right-hand half of the page:

VIII

there we sawe other verye highe lande to the N: W: wh[ich

seemed] muche neerer then the other high lande: & other

broken landes to the W: of indifferent height,

we were at this tyme in 43:3½ June 9. & had 60: fath: wate[r]

softe oaze.

Below, to the left of the circle, is a crude sketch of a mountain with three peaks, and to the left of it what appears to be meant for rising land with a single peak. Over these is the legend:

IX

the 3: turkes heades

some 4 le: from the litle rocke.

In view of legend I, it seems certain that the center of the circle represents the point whence Mount Desert was sighted at 3 p. m. June 8. Legend II (“12 leagues,” altered from “15”), appears to be a guess at the distance, differing from the fifteen leagues in the Journal, which again was altered from eight. The left-hand sketch, with the legend “thus it seemed at first in the evening,”500 represents the view of Mount Desert from that point. The height is exaggerated, even for a distance of four or five leagues, but the Mount Desert hills from that direction do appear foreshortened in two masses, representing the higher mountains to the East of Somes’s Sound, and the lower ones to the westward.

Having made this landfall at 3 p. m. on June 8, the Arbella tacked and stood W. S. W., says the Journal. In order to permit her to take that course, the wind must have shifted either to the E. of S., or to N. W. by N. I have no doubt that it took the latter shift, for Winthrop immediately records:

We had now fair sunshine weather, and so pleasant a sweet ayre as did muche refreshe vs, and there came a smell off the shore like the smell of a garden.

There came a wild pigeon into our ship, and another small land bird.

Anyone who has sailed in our waters can picture the scene. It was one of those heaven-sent June days in the Gulf of Maine. A light off-shore breeze, fleecy clouds rolling up from over the land; sky, Mount Desert, and ocean in three deepening shades of blue; and the air filled with the spicy fragrance of the Maine summer.

As Winthrop makes no note of a new course until the next day, the Arbella probably steered W. S. W. through the night. This course would have taken her within fifteen miles of Mount Desert Rock, which lies about ten miles south of Mount Desert Island. But even if she came within that distance of the rock in daylight, which she could hardly have done, it is not likely that the rock would have been seen. Mount Desert rock is very low, and even with the modern lighthouse, difficult to pick up within ten or twelve miles. I assume that the off-shore wind died at nightfall and that the Arbella did not do better than one and a half or two knots during the night of June 8–9.

On Wednesday, June 9, says the Journal,

In the morning the wind easterly, but grew presently calm. Now we had verye faire weather, and warm about noon the wind came to S: W: so we stood W: N: W: wth a handsome gale . . .

This drifting on Wednesday morning in a light easterly and calm would have brought the Arbella about noon, when the wind came up from the S. W., to about latitude 43° 40′, longitude 68° 10′.

Does Winthrop’s sketch of an extended line of hills, with legend IV, “thus it seemed next daye,” represent Mount Desert as it appeared while the Arbella was becalmed on the morning of June 9? At that time Mount Desert would have been distant thirty-five or forty miles to the N. N. E., and the mountains would seem strung out in a line, although without that discrepancy in height between the western and the eastern group which Winthrop shows. Or does this sketch present the Penobscot or Camden Hills with their three conspicuous heights (Battie, eight hundred feet, Bald Rock, eleven hundred feet, and Megunticook, thirteen hundred and eighty feet) and lower hills to the north and south? Moreover, the line drawn from the base of the highest hill contains legend V “10[ ]: le[a]g[ues], N:b:W:” If my other calculations are correct, Mount Desert would have borne about N. N. E. on the morning of the ninth, and the distance would have been nearer thirteen than ten leagues. Winthrop indicates in his Journal for the ninth (quoted below) that he confused the Camden Hills with Mount Desert, and decided that what he had seen the day before was some high land east of Mount Desert.501 Approaching the Maine Coast from the southwest, the Camden Hills and Mount Desert are easily confused; but approaching it from the eastward, as the Arbella did, it would seem unlikely that any seaman would confuse hills bearing N. by W. on the ninth with those which he had seen the previous afternoon, bearing N. W. But it must be admitted that, as a representation of the Camden Hills, this sketch is most inaccurate. The characteristic feature of them, as seen from that angle, is a large gap between the higher northern group and the lower southern group. It is, however, amazing what mistakes in observation were made by discoverers and cartographers before the period of exact coast surveys.

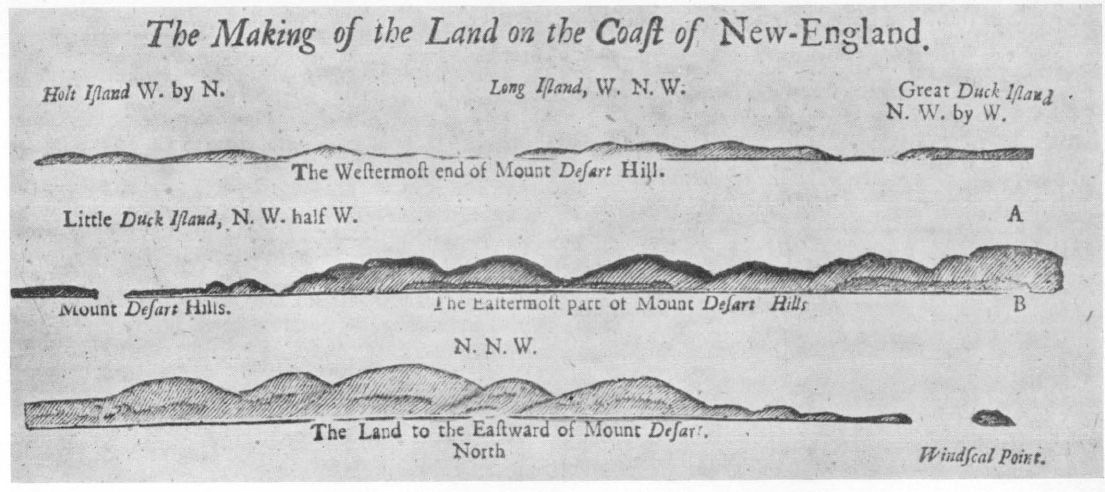

SILHOUETTES OF THE MAINE COAST IN THE ENGLISH PILOT, 1729

reproduced for the colonial society of massachusetts

Let us compare Winthrop’s sketch and data with the sketches of profiles in The English Pilot, The Fourth Book, containing Charts of the North Part of America . . . , London, 1729.502 The first line represents Isle au Haut, Swans Island, Outer Long Island, and Great Duck, seen from a point not far from Mount Desert Rock. The next, or second, line represents Mount Desert, seen from a point roughly ten miles to the southward. The legend on the third, “The Land to the Eastward of Mount Desart” is an error; these are characteristic profiles of the eastern range of the Mount Desert Hills, as seen from a point to the south and east, ten miles or so distant.503 The fourth line of the silhouettes is a fairly accurate representation of Mount Desert as it appears from about the direction of the Arbella’s landfall, but a little more to the westward and at half the distance. The mountains seem combined in two groups, the larger to the eastward.

A comparison with the map of New England which appears in The English Pilot, The Fourth Book, edition 1729, is also suggestive.504 Although Mount Desert Island had been discovered and described as an island by Champlain a century and a quarter before, it does not appear on this map; instead, the Mount Desert hills are arranged in line along Eggemoggin Reach. The Fox Islands are shown as a single block, with no thoroughfare. A non-existent island is placed near Mount Desert Rock. The axis of the Penobscot or Camden Hills is four or five points out. But the resemblance between the profile of the Penobscot Hills and Winthrop’s second sketch is striking. If they appeared thus to the compiler of this map, may they not have appeared so to Winthrop?

Continuing the Journal from noon, June 9:

About noon the wind came to S: W: so we stood W: N: W: wth a handsome gale & had the maine land vpon or starbod all that daye about 8 or 10505 leagues off. It is verye highe lande lying in many hilles verye vnequall.

This fits in perfectly with a W. N. W. course from latitude 43° 40′, longitude 68° 10′. Green Mountain, and four other Mount Desert summits over one thousand feet, Blue Hill (nine hundred and forty feet), Isle au Haut (four hundred and sixty feet), the hills near Castine (about five hundred feet) and the Camden Hills would be conspicuous landmarks. Continuing his Journal:

At night we saw many small Ilads being low lande between vs & the maine about 5: or 6: leg: off vs & about 3 leg: from vs towards the main a small rock a little aboue water.

Compare this with legend VI:

when the great hill in the maine Lande

laye N: & b: E: from vs, the rock laye E by N.

& the 5: or 6: smale Ilandes of low land laye the

foremost N: & the rest more W: eache after other

& seemed to be middwaye towards the mayn

with the sketch of rock and islands, and the accompanying legend VII:

5. or 6. lowe ilandes lye ther

this rock lyes thus

a litle aboue water. neere no lande by 3: or 4: leg.

Here we have as neat a bit of identification as we can find in the voyage. There is only one rock on the Maine coast which satisfies both sketch and description: Matinicus Rock, near a group of several low islands, and well out to sea. Although the size of a small island, and rising thirty-five or forty feet above high-water mark, Matinicus Rock is completely swept by winter seas, and contains no vegetation but a little grass. Cross bearings N. by E. on Mount Megunticook of the Camden Hills (thirteen hundred and eighty feet, which I take to be “the great hill in the maine Lande”), and E. by N. on Matinicus Rock, give as a latitude 43° 44′, longitude 68° 58′. This point the Arbella could have reached at 7 p. m. June 9, steering a W. S. W. course at five knots since noon, assuming the earlier calculations to be correct. If we plot this point on the chart, it is evident that to anyone taking bearings from it, Matinicus Rock, Ragged Island, and Matinicus Island (the Nomans Land of the 1729 chart) would be in just the relationship shown by Winthrop’s sketch. The other islands, not shown in his sketch, are Wooden Ball, Seal, Green, and Metinic. They lie from that point “the foremost north and the rest more westerly . . . midwaye towards the mayne” just as legend VI declares. Matinicus Rock is actually two, not three leagues distant from the point where the cross-bearings meet; but it is a difficult matter to judge the distance of a rock at sea, when there is nothing near or upon it to measure its height or extent.

SILHOUETTES OF THE MAINE COAST IN THE ENGLISH PILOT, 1729

reproduced for the colonial society of massachusetts

Continuing the Journal for June 9:

At night we sou[n]ded & had softe oazy gronde at 60: fath: so the wind being now skant at W: we tacked again and stood S: S: W: we were now in 43:½ This highe land wh we sawe we iudged to be the W: Cape of the great Baye wh goeth towarde Porte Royall, caled Mo desert or mount Mansell & no Ilad but part of the main.506 In the night the wind shifted ofte.

Compare legend VIII:

there we sawe other verye highe lande to the N: W: wh[ich

seemed] muche neerer then the other high lande: & other

broken landes. . . .

we were at this tyme in 43: ½ June 9. & had 60: fath: wate[r]

softe oaze

Between six and ten miles westerly from the point whence these cross-bearings were taken, there are many places where the water is sixty fathom deep. Over an area of several square miles the bottom is brown mud, according to modern charts. I take it that the Arbella sounded, tacked, and stood W. S. W. at about latitude 43° 42′, longitude 69° 12′. Winthrop says 43° 30′, which is near enough for observations taken with the cross-staff.

The “verye highe lande to the N. W. . . . muche neerer then the other high lande” is however, puzzling. There is no very high land on the mainland in that direction; only hills, which rise to a maximum height of six hundred and forty-four feet. It is barely possible that Winthrop meant the high island of Monhegan which (if I have selected the right sixty fathom spot) then bore seven miles N. W. by W. And it is strange that he does not mention Monhegan, for which he had mistaken Mount Desert the previous day. Yet no seaman could have mistaken Monhegan for anything but an island, unless deceived by mist or fog.

In the night of June 9–10 “the wind shifted ofte”; on the morning of June 10 “the wind S: Sc by W: till 5: in the morning a thick fogge then it cleared vp wth faire weather, but somewhat closse. . . .” The course was W. by S. On account of the evidently erratic course the previous night, we can place the Arbella’s position on the morning of the 10th only by working back from her next landfall, allowing a speed of five knots. That gives us latitude 43° 35′, longitude 69° 34′, at 8 a. m. June 10.

The Journal continues:

after we had runne some 10: le: W: & by S: we lost sight of the former land but made other high land on our starre board as far of as we could descry but we lost it again.

I take it that “the former land” means the Camden Hills, and that Winthrop counts his ten leagues from the cross-bearings the night before, otherwise these hills would have long been out of sight. The other high land to starboard must have been the White Mountains. As a legend on Captain Holland’s Chart of New England (London, 1794) correctly declares, “the White Hills are a Great Landmark to Seamen, and may be seen many Leagues off at Sea, like a Bright Cloud above the Horizon.” My guess is that the Arbella sighted the White Mountains about 10 a. m. when my calculations bring her about twenty miles off Portland Head.

Continuing the Journal:

The wind continued all this daye at S. a stiffe steddy gale yet we bare all or sayles & stood W: S: W: about 4: in the after noon we made land on or starboard bowe, called the 3: turkes heads, being a ridge of 3 hilles vpon the mayn whereof the southmost is the greatest, it lies near Aquamenticus. we descried also an other hill more northard which lies by Cape Porpus. we sawe also ahead of us some 4: le: frm shore a small rocke, called Boone Ile,507 not above a flight shot over, which hath a dangerous shoal to the east & by S. of it some 2: le: in lengthe. we kept or luff & weathered it, & left it on or starbord about 2: miles off. towards night we might see the trees in all places very playnly & a small hill to the southward of the Turks heads; all the rest of the land to the S: was plain lowe land: here we had a fine fresh smell from shore. Then least we should not get clear of the ledge of rockes wh lye vnder water from wthin a flight shot of the sd rocke (called Boone Ile,) which we had now brought N: E: from vs towarde Pascataquac: we tacked & stood S: E: wth a stiffe gale at S: by W:

CHART OF THE GULF OF MAINE COAST IN THE ENGLISH PILOT. 1729

reproduced for the colonial society of massachusetts

Mr. Ware discusses the identity of the Three Turks’ Heads in his article,508 and concludes that it is Mount Agamenticus, near York, Maine. This conclusion is confirmed by Winthrop’s sketch, and by legend IX, which gives almost the exact distance of Mount Agamenticus from Boon Island. Agamenticus is represented with three peaks on the chart in The English Pilot, 1729 edition, and Winthrop’s sketch closely resembles the silhouette of “Wells Hill” in the same book.509

This part of Winthrop’s course is perfectly clear. After sighting simultaneously Boon Island, Agamenticus, and Cape Porpoise, the Arbella kept her luff, i. e., remained close hauled on the port tack heading W. S. W., and left Boon Island ledge two miles to starboard. Boon Island ledge lies about three miles E. by S. of Boon Island, and is a pinnacle rock; but there is another rock between it and the island which breaks in heavy weather at low water, and thus may have suggested to Winthrop that there was a continuous shoal. Having weathered Boon Island ledge the wind hauled a bit to the westward, which made the Arbella pass uncomfortably close to Boon Island. After bringing it to bear northeasterly, the Captain wisely decided to tack and stand off-shore lest he run afoul of the rocks to the west and south of Boon.

During the night of June 10–11 the Arbella probably took a long leg-off-shore, standing on again the morning of June 11. She came within two leagues of the Isles of Shoales, says Winthrop, and sighted several fishing shallops. As the wind still blew from the S. W. it was hopeless to make Salem that day, and the Arbella “stood to & agn all this day wthin sight of Cape Ann,” doing a little mackerel fishing on the side.

Saturday 12. About 4: in the morning we were neere or porte. we shott of 2: peeces of ordinance, & sent or skiffe to Mr Peirce his shippe (wh laye in the harbour & had been here dayes before) about an houer after . . .

On one of the pages in the back of Winthrop’s Journal we find the small outline chart of Cape Ann, which is here reproduced, in facsimile with its legend.510 The sketch shows the shore line of Cape Ann from Gloucester Harbor to Salem, when the Arbella passed, but the legend gives data on the islands off Cape Ann, which are not represented in the chart.

About the E: point of Cape Anne

lye 3: or 4: ilandes which appeare aboue

water & a ledge of rockes vnder water

lyeth to the eastwd of the bigger E:

Ilande, which ridge stretcheth about ½ mile

to the E: but a mile or 2: to the

S: of the sd Ilads is deepe

water aboue 30: fath:

the most northeast of all the sd Ilandes is

a small Rocke, bare without wood or ought

vpon it, the rest have shrubbes.

wthin 5: or 6: le: of Cape Anne are

store of mackerell.

The Iles of Sholes are woodye

The three islands are Thatcher’s (the larger and more easterly), Milk, and Straitsmouth. These are the islands to which Captian John Smith gave the name the Three Turks’ Heads, after his famous if self-bestowed, coat of arms in 1614.511 The soundings on the modern chart south of Thatcher’s, agree with Winthrop. The bare rock to the northeast of them is the Salvages.512

Winthrop Chart of the Coast from Gloucester to Marblehead

What point had the Arbella reached at 4 a. m. on the twelfth, when she was near her port? From this accurate description of the islands, it would seem that she must have passed them no earlier than sunrise; but possibly Winthrop made his observations of them the previous day, when “within sight of Cape Ann.” Thatcher Island is not what a modern yachtsman would call near Salem, but it may have seemed near enough to people who had been two months at sea. At any rate, the Arbella was some miles east of Bakers Island at 4 a. m., as the next entry proves. Winthrop’s chart of the approach to Salem is interesting as the most accurate chart of that shore which has come down to us, previous to the one in The English Pilot, The Fourth Book, edition of 1765. The detail, especially as to the interior of Gloucester Harbor and Salem Harbor, is too full and accurate to have been made by anyone merely sailing along the coast and sketching what he observed. Probably this chart represents a careful survey made by someone who came out with Endecott or even earlier. We may suppose that the original was in the hands of Captain Milborne, and that Winthrop made a copy for his journal.

Winthrop makes no mention of the wind on the morning of June 12. I assume that it was very light, or it would not have been worth while to send ahead the skiff, which could not have been rowed faster than three knots for a long distance. As no tacking is mentioned, there must have been a light easterly or an off-shore breeze, either of which is likely to come up after a spell of southerly. I rather think that it was a light easterly, as an off-shore wind would have headed the Arbella, later in the morning. The shallops which she encountered must then have been under oars. It was low water at about three that morning, so the Arbella had a favorable current along the coast.

Continuing the Journal, “about an hour” after hoisting out the skiff, i. e., about 5 a. m., “mr Allerton came aborde vs in a shallop as he was sayl[in]g to Pemaquid.” Isaac Allerton, a Pilgrim Father, more renowned for sharp trading than for piety, was thoroughly acquainted with these waters, and doubtless gave Captain Milborne the proper directions for the ship channel and the anchorage beyond.

. . . sayl[in]g to Pemaquid, as we stood towards the harbour we saw another shallop coming to vs so we stood in to meet her, & passed through the narrow streight between Bakers Ile & Little Ile, & came to an anchor a little wthin the Ilads.

This, and the later statement that the shore of Cape Ann lay very near her anchorage, are the only indications we have for the concluding hours of the Arbella’s course.

If the Arbella “stood in” to meet the second shallop, she had probably been sailing further off-shore than the straight course demanded. She then took the narrow strait “between Bakers Ile & Little Ile,” which still is the main ship channel to Salem Harbor. Bakers Island, still so called, was named after an early settler who came over with Endecott. Allerton had probably told Winthrop the name that morning. Little Island has been called Little Misery for the last two hundred and fifty years.513 The “narrow streight” is actually about nine hundred yards wide, but would appear narrow enough to people coming from the open sea. One can look straight through it and out to sea from Salem itself; and to the people there, aroused by the heralding gun and by the messenger skiff, the sight of the Arbella with colors flying and sails bellying to a light easterly breeze, must have been an impressive and cheering sight.

Winthrop’s chart shows Bakers and the Little Island in their correct relative position, together with Great Misery Island, and two others which I take to be House Island and Saul’s Rock.

Having passed through the strait, she “came to an anchor a little wthin the Ilads.” The Arbella must have continued her course to good holding ground, which according to modern charts is not reached until a point about one and three-eighths miles N. N. W. of Little Misery, off Plum Cove. She may have continued a mile and a quarter beyond that to Hospital Point, which would have been much nearer her final destination. I believe, for the following reasons, that she anchored at about 10 a. m., June 12, from a quarter to a half a mile off Plum Cove. (1) Winthrop says she anchored a little within the islands; hence she must have been nearer to the islands than to the harbor. (2) High water came that morning at a little after nine, so by the time the Arbella reached Plum Cove, sailing 2 to 2½ knots with a light wind (if my calculations are correct), the ebb tide would have been setting against her, and further progress would have been difficult until the wind freshened or the tide changed. (3) This spot off Plum Cove is one of two places in Salem Bay where Bowditch places the symbol for good anchorage on his chart of 1806. It is a favorite anchorage today for deep-water vessels, such as oil-tankers.

And perhaps I should add, to be perfectly candid, that my good friends the Lorings live on Plum Cove, and I rather like to imagine the stately Arbella anchoring off a place where I have enjoyed many happy hours. But I am willing to concede that she may have anchored anywhere off the Beverly shore between Allens Head and Hospital Point.

Let us consider a rival theory, that the Arbella anchored off Manchester, the next town east of Beverly. It is so stated in the Rev. D. F. Lamson’s History of the Town of Manchester, which appeared in 1895. The alleged event was played up in a pageant at Manchester that year, and so has been accepted by many dwellers on the North Shore as a venerable tradition and incontestable fact. The relative claims of Beverly and Manchester were discussed in the Historical Collections of the Essex Institute for 1898. Therein the anonymous advocate for Manchester is able to find no better basis for his claim than the statement “It is a tradition as old as the settlement of Manchester, that the ‘Sagamore of Agawam’ was Masconomo, that he lived in Manchester, and feasted Governor Winthrop’s party on strawberries . . . It was told to the writer by his father, who was born in 1785.”514

There are several reasons, each conclusive, why the Arbella could not have anchored in Manchester Harbor. (1) Winthrop distinctly states that he passed through the strait between Baker’s Island and Little Island, which there is no doubt means Little Misery.515 The Manchester people assert that the Little Island means House Island; but there is no strait between Bakers Island and House Island. They lie a mile apart, with a ledge between. (2) The Arbella’s destination was Salem, and there is no reason why she should have deliberately gone out of her way to enter a bad harbor with a dangerous entrance when the day was yet young and wind and tide favoring. (3) It would have been a five-mile row from Manchester Harbor to the settlement at Salem. (4) Winthrop’s own chart shows a very slight indentation of the coast line at a point corresponding to Manchester Harbor.

Having anchored off the Beverly shore in the morning of June 12, the Arbella was first visited by Captain Peirce of the Lyon, which had sailed from Bristol in February and arrived at Salem in May. Captain Peirce returned to fetch Captain John Endecott, who came aboard “about 2: of the clock” with the Rev. Samuel Skelton and a certain Captain Levett. The Journal continues:

We that were of the assistants & some other gent[lemen], & some of the women & or Capt returned wth them to Nahumkeck, where we supped with a good venyson pastye, & good beere, & at night we returned to or shippe, but some of the women stayd behind. In the meane tyme most of or people went on shore vpon the land of Cape Ann516 wh laye verye neare vs, & gath: store of fine strawbe[rries]517

If the Arbella was anchored off Plum Cove, it was a row of three miles to the settlement at “Nahumkeck” (Salem), or two miles if she was anchored off Hospital Point. The passengers may have been landed on Plum Cove Beach, or Mingo Beach, or some other place along the shore; and there are several rocky headlands where wild strawberries grew until within the memory of people now living. Strawberries must have been refreshment indeed to the company of the Arbella, most of whom had been on shipboard since March 28.

June 13 being the Lord’s Day, the Arbella did not leave her anchorage. Masconomo, the sagamore of Agawam, came aboard with one of his men to pay his respects and see what he could pick up. In the afternoon the Arbella’s crew sighted their consort the Jewel, struggling with a light wind against the tide, so despite Sabbatarian prejudices they manned their skiff and “wafted her in.”518 The Jewel “went as near the harbour as the tyde & winde would suffer” — probably nearer than the Arbella’s anchorage.

THE COURSE OF THE ARBELLA. JUNE 12–JUNE 14

reproduced for the colonial society of massachusetts from a drawing by samuel c. clough

On Monday, June 14, it was low water about 4:30 a. m. Winthrop’s Journal states:

In the morning early we weyed anchor, & the wind being against vs & the Channell so narrow as we could not well turne in, we warped in or shippe, & came to an anchor in the inward harbor.

What was this inward harbor which they entered for their final anchorage? It seems to me that Winthrop’s brief description fits Beverly Harbor rather than Salem Harbor proper. The Beverly channel was much more narrow and crooked then than now, and in the mouth of the North River, near the “old planters” houses (just above the present railway bridge) the Arbella could have anchored in fifteen to twenty feet of water. There is, however, another possibility. She may have entered Salem Harbor, and have been warped up the narrow channel of the South River, with a rising tide. Most of the South River has been filled in during the last hundred years, but on Bowditch’s chart of 1806 it is shown extending to a point near the present railway station, and is so shown on Winthrop’s chart. This place would have been much handier to the houses built by Governor Endecott and his followers, on the ridge just east of the present railway tunnel, than the North River would have been. The South River, however, was completely dry at low water, according to Bowditch’s chart of 1806 and the Atlantic Neptune chart of 1773; and there is no reason to suppose that it afforded an anchorage in 1630. The Arbella could only have floated there at high tide, and Winthrop’s Journal distinctly states that she “came to an anchor.” No master of a heavily-laden vessel the size of the Arbella would have cared to place her in a position where she would ground between tides, especially in a place where she was left completely high and dry. Hence I conclude that the mouth of the North River in Beverly Harbor, and not the South River in Salem Harbor, was the final anchorage of the Arbella.

Winthrop thus concludes his Journal of the voyage, on June 14:

In the afternoon we went wth most of or company on shore, & or Capt gave vs 5: peeces.

So ended, with a hearty salute, the voyage of the Arbella, flagship of the Winthrop fleet, bringing the Governor and Company of the Massachusetts Bay to the haven where they would be, and the royal charter to the place of its jurisdiction. It may be said that when Governor Winthrop stepped ashore on June 12, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts came into being.