Songs to Cultivate the Sensations of Freedom

Monday, August 14, 1769:

Dined with 350 Sons of Liberty at Robinsons, the Sign of Liberty Tree in Dorchester. We had two Tables laid in the open Field by the Barn, with between 300 and 400 Plates. . . . After Dinner was over and the Toasts drank we were diverted with Mr. Balch’s Mimickry. . . . We had also the Liberty Song—that by the Farmer . . . and the whole Company joined in the Chorus. This is cultivating the Sensations of Freedom.

—John Adams, Diary1

TWENTY years ago it was a bit difficult to understand the role of topical songs in the American Revolution. Now with “We shall overcome” and other civil-rights songs still lingering in our memories, it is somewhat easier. There are more than 300 song texts still extant on issues and events of the rebellion. Some were engraved with sheet music and with caricatures in England; others were printed in newspapers, broadsides, and songsters in America and England between 1760 and 1785.2

While none of these songs had the political clout which “Lillibulero” and the “Marseillaise” had on their times, some were as well known in the Revolutionary era as “The battle hymn of the republic” was known in the 1860s, and as well as “We shall overcome” has been known in our time. Contemporary descriptions such as that from John Adams’ Diary, quoted above, are rare, but the songs of the Revolutionary War are also significant because a number of the texts, in spite of the customary pseudonyms, have been attributed to such leaders and writers as John Dickinson, Benjamin Franklin, Francis Hopkinson, Arthur Lee, Joseph Warren, Mercy Otis Warren, and Thomas Paine.

Antiquarians like Frank Moore who have collected and published song texts of the American Revolution, and the historians who have used such anthologies, sometimes seem embarrassed by the sub-literary quality of the verse.3 One must remember, however, that the song texts were propaganda and should be judged by their meaning to the people to whom they were addressed, rather than by an abstract literary standard. Recent social historians, such as Davidson4 and Granger,5 have given more pertinent analyses of the song texts’ propaganda functions, but theirs is a science of exposition by dissection wherein one clearly sees the veins and muscles “laid out,” but seldom the viable body of a song. Both approaches neglect the fact that a song text is only part of a song which is meant to be sung, since essentially a “song” is a temporal trilogy of words, music, and at least one singer.

For instance:

We will overcome,

We will overcome,

We will overcome some day,

Oh deep in my heart

I do believe

We will overcome some day.

Subliterary? Perhaps. But, carried by its simple twentieth-century folk version of the eighteenth-century “Sicilian hymn,” it is as powerful as any national hymn.6 Sung by thousands of black and white Americans who “joined in the Chorus” as they marched up Constitution Avenue to the Lincoln Memorial during the Freedom March, August 28, 1963,7 it was “cultivating the Sensations of Freedom.” But, if the text were deprived of its music, of its harmony, and taken out of the context of the freedom marches and rallies of the 1960s, a twenty-second-century historian might well say, “one cannot imagine anyone’s actually singing the song we have here,” thus, unconsciously, paraphrasing two twentieth-century writers’ comments on song texts of the American Revolution.8

The majority of the Revolutionary War song texts certainly were intended to be sung. Of the more than 300 song texts in my files at least 180 give clear music cues: an indicated tune, an imitative first line or chorus, and, in some of the English Whig and Tory songs, even engraved music is included. When reunited with their intended tunes they sing very well today. Of the remaining song texts, lacking music cues, many are in ballad meter, for which dozens of suitable eighteenth-century tunes exist.

But, the music, the language, and the vocal requirements for most of these songs are quite different from American popular and folk music of the last one hundred years. Most Revolutionary War songs were adapted from the patriotic, pastoral, and satirical lyrics and tunes of mid-eighteenth-century ballad operas and pleasure garden entertainments—a melodic and lyrical genre which went out of style in both England and America after 1800.

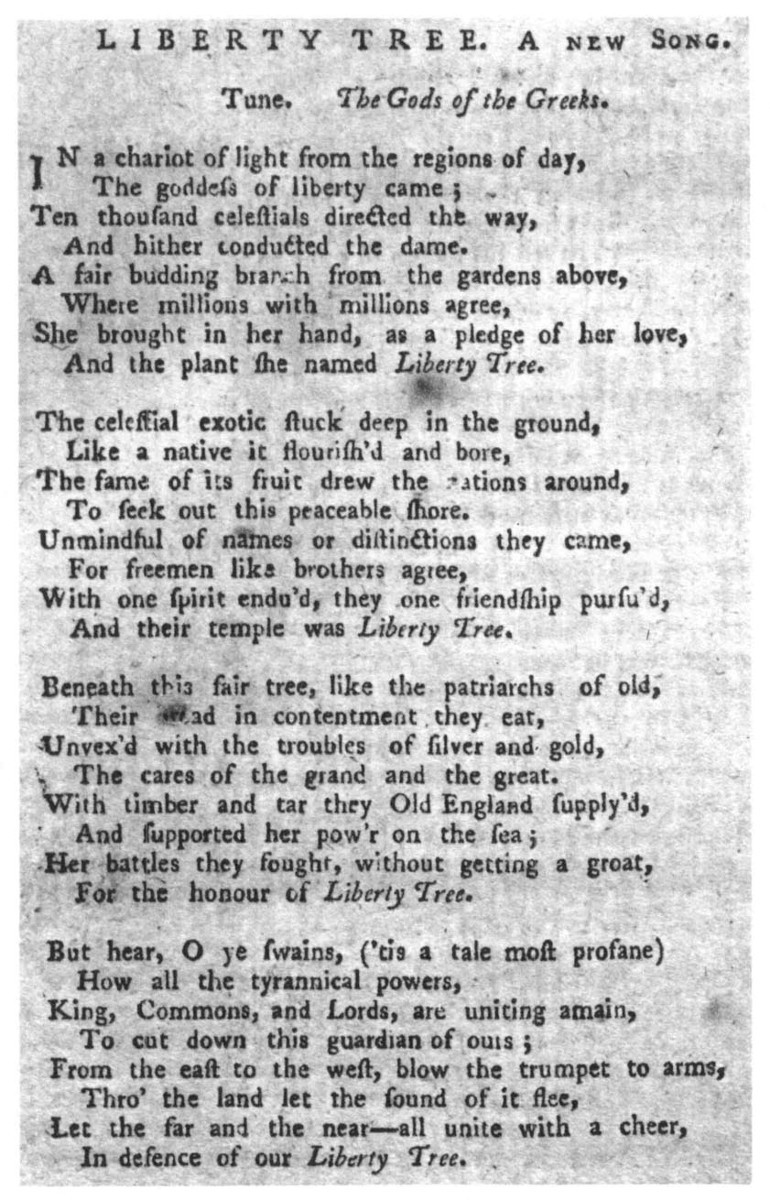

Metrical psalms and hymn texts were sung to many different tunes, and broadside texts could be sung to different ballad tunes, but almost all secular popular and topical songs of the late eighteenth century circulated as “set tunes,” with a stable text/tune combination that could last for decades. When a colonial writer indicated a tune, or implied a tune in an imitative first line or chorus, that tune, and the text associated with that tune name, frequently indicated the mood and intent of his song. It was not casual or accidental that Paine, writing Liberty Tree, cited as his tune “Gods of the Greeks,” a song that was also titled The Origin of English Liberty,9 when it was published in London in 1760 (fig. 78). Paine’s text is not a recasting of “Gods of the Greeks” text, but it utilizes the same general conceit of gods and godlike spirits who bestow liberty or the symbols of liberty on their favored lands. Thus, Paine’s announcement of his tune suggested immediately the mood of his song to colonial singers.

Similarly, the colonial singer could always anticipate low comedy with a light satirical and perhaps scatological text when he read or heard the first strains of “Derry down,” “Doodle doo,” or “Yankee Doodle.”10 He could expect the word play we associate with a Gilbert and Sullivan patter song for a text set to “The queen’s old courtier,” and bitter satire to “Ye medley of mortals,” which was a kind of eighteenth-century musical Ship of Fools. He could also expect witty, sophisticated, and somewhat lighter satire to the tunes of “A-begging we will go” and “Hey my kitten.”

Texts to these tunes would ridicule the enemy but would not usually attempt to appeal to the patriot’s ardor. That appeal generally was reserved for hortative texts to tunes like “Heart of oak,” “The British grenadiers,” “Rule Britannia,” “Smile, Britannia,” and “God save the king.”

It is essential then to remember that while tunes are neutral in themselves, they can acquire overtones when combined with a text associated with emotional occasions. Sensing these overtones in eighteenth-century songs takes time and study, but many American readers can appreciate the implications of two well-known American tunes more than a hundred years after the events which established their notoriety. One needs only to imagine a group of northern blacks whistling “Marching through Georgia” on the streets of Atlanta; or, the obverse, a group of southern white farmers singing “Dixie” in minstrel dialect on the streets of Harlem.

Eighteenth-century people had the same kinds of reactions to some of their tunes. It would have been a most foolhardy loyalist who dared whistle “When the king enjoys his own again,”11 while a mob was burning the effigies of stamp tax collectors.

Except for the speculative adaptation of “The [Irish] wash woman” to The Irishman’s Epistle, all the song texts which follow have been adapted to their originally intended tunes.

The rhymes occasionally look odd. Loyal rhymed with trial, and arms rhymed with swarms in The Rebels; war with tar, in The Halcyon Days; and America successively rhymed with sway, prey, away, betray, array, and obey, making it quite clear that the proper noun was pronouced “Americay,” and not “Americuh,” at least in the New Massachusetts Liberty Song. This was not provincial or colonial ignorance. Pronunciation of the English language, even in London, during the eighteenth century was even less settled than spelling.

A. S. Collins12 notes that there was an English spelling dictionary by 1702, an etymological dictionary by 1721, and Johnson’s monumental dictionary by 1755. But Johnson sought only to establish standard meanings and accentuation, and declined to give pronunciations because good speakers showed such variety. Collins further states that not until Thomas Sheridan published his Complete Dictionary of the English Language in 1780 was there an authoritive guide to pronunciation. Twentieth-century singers are I think generally best advised to ignore the rhyme schemes and to use modern pronunciations. Obsolete pronunciations can bring an audience to laughter, not intended by the author, and tend to draw attention from the subject, and the music, to the pronunciation for its own sake.

Some of the tunes may be found in Chappell, Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time, and some in Simpson, British Broadside Ballad and Its Music, but neither writer treated in depth the popular music from 1725 to 1775 which is the vehicle for many of the Revolutionary song texts; so “Doodle doo,” “Gods of the Greeks,” and “Black joke” are not in their studies. Furthermore, Chappell’s music was arranged and sometimes “corrected” to mid-nineteenth-century taste. Simpson prints only the melodies, which separates one from the nuances of text/tune combinations which are important to parodists. Therefore, all the music which follows has been found or reexamined in period copies as cited in the notes to each song.

The musical adaptations in the accompanying illustrations have been written in modern professional style, using beamed eighth and sixteenth notes and showing key signatures and time signatures on first lines only. Some songs have been transposed, the better to fit the staff and the voice. Small notes above the staff indicate time values of the original melody.

The texts also have been slightly modernized in form to speed the way for those who wish vocally to cultivate “the Sensations of Freedom.” To facilitate this, the period copy of the text used faces each adaptation to provide all the verses in their original order and to show the song text in its original style. Generally the verses selected for inclusion with the music are those which show a variety of problems with syllables and phrasing, but any singer working with eighteenth-century music will have to learn to cope with the inevitable irregularities.

acknowledgements

David Robertson, Old Sturbridge Village Music Department, edited and adapted the texts to the tunes for publication.

Most of the search for original song texts in eighteenth-century newspapers and illustrations was done by Elizabeth Schrader. We both are most grateful to the directors and staffs of the American Antiquarian Society, the Boston Athenæum, the Music Division and the Division of Prints and Drawings of the British Museum, the Cambridge University Library, The Connecticut Historical Society, the Houghton Library of Harvard University, the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, the Massachusetts Historical Society, and the New Hampshire Historical Society.

Notes to the Songs

These notes include the complete bibliographical information for each text and tune cited. The footnotes which follow are reserved for supplementary information. These abbreviations have been used:

Chappell: William Chappell, Ballad Literature and Popular Music of the Olden Time (London, 1859).

Simpson: Claude Simpson, The British Broadside Ballad and Its Music (New Brunswick, 1966).

Moore: Frank Moore, Songs and Ballads of the American Revolution (New York, 1855).

Marshall Collection: The Julian Marshall Collection of single sheet songs in Houghton Library, Harvard University. They are not catalogued, but are arranged alphabetically by printer’s titles.

Eighteenth-century songs frequently were published without titles. The titles which follow in italics are those originally published with the song text, or tune, or added soon after. Titles in brackets are derived from first lines, or choruses, or were supplied by Moore or by the writer. Tune titles are in quotation marks. Slight changes have been made in the music to fit the words to it.

The Liberty Song

text: John Adams’ cryptic comment quoted in the headnote, “We had also the Liberty Song—that by the Farmer . . . ,” shows he knew the song was written by John Dickinson (the author of “The Letters of a Farmer in Pennsylvania”), even though it was published anonymously. Other Revolutionary War songs were published earlier, but The Liberty Song was the first American “patriotic song” to receive widespread acceptance, and we can follow its course through the colonies week by week in the newspapers during the summer of 1768 after its initial publication in the Pennsylvania Chronicle, July 4, 1768. It was also the first of very few American topical songs to be published during the Revolution with the music as well as the words. That printing, in Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanack, 1769 (Evans 11112), was reproduced in Series of Old American Songs, ed. S. Foster Damon (Providence, 1936), no. 3.

Schlesinger notes that Dickinson sent a copy of the song text to James Otis with the comment “Cardinal de Retz always inforced his political operations by songs.”13

This text is from the Boston Gazette for July 18, 1768 (fig. 79).

tune: The original song “Heart of oak” was first published in single sheet music as “Come cheer up, my lads. A song sung by Mr. Champnes in Harlequin’s Invasion . . .” to celebrate 1759, the year of decisive English victories over the French. Chappell, ii, 715–717, provides a copy and a short account of the original song. With verses by David Garrick and music by William Boyce, it became extremely popular in its own right and the tune became the second most popular vehicle for Anglo-American topical song texts. The “Derry down” tune was used for more song texts in the Revolution but these tended to be ephemeral and of limited circulation, while Revolutionary song texts to “Hearts of oak,” as it came to be called, were being reprinted in broadsides in 1814 (fig. 80).

Copies of the tune for this adaptation date from 1759 and are located in the British Museum, Music, g.307 #41 and g.316 #75.

[Come shake your dull Noddles]

text: The Liberty Song evidently was widely circulated in Boston from late July to mid-September 1768 because a loyalist responded with the parody Come shake your dull Noddles. When printed in the Boston Gazette, September 26, 1768, it was headed “Last Tuesday the following Song made its Appearance from a Garret at C-st-c W-----m [Castle William].” This may imply that the original copy was a broadside, but it suggests authorship by ministerial supporters, since Castle William was a fort and an army garrison. The text is remarkably more vituperative than the Liberty Song which is being parodied, but it should be remembered that the parody is also a response to the “mob” actions of the Boston Sons of Liberty, from whom no government official’s home was safe, if he attempted to enforce the royal edicts.

The text is from the Boston Gazette, September 26, 1768 (fig. 81).

tune: Same as figure 80.

The Parody parodized, or the Massachusetts Song of Liberty

text: This song had a remarkably long life for a parody. It was revived during the War of 1812 by Nathaniel Coverly, Jr., in a broadside which is now in volume ii, number 79, of the Isaiah Thomas Ballad Collection in the American Antiquarian Society. The verses have been attributed both to Benjamin Church and to Mercy Warren.

The text is from the Boston Gazette, October 3, 1768 (fig. 82). For other comments and the version in Bickerstaff’s Boston Almanack, 1770, see Smith, “Broadsides and Their Music in Colonial America,” figure 168.

tune: Same as figure 80.

[Burn All]

text: This is one of the earliest and most vehement anti-stamp tax songs. An unusually detailed story of its first appearance at Newport, Rhode Island, was published with the song text in the Boston Evening Post for September 2, 1765, as reproduced here. The New-Hampshire Gazette, September 6, 1765, also carried the account. Lemay calls this New Hampshire copy a “reprint” of the version printed in the Connecticut Gazette at New Haven on the same day, that is, September 6, 1765.14 Since the two towns are nearly 200 miles apart, the coincidence of dates seems rather to suggest that each newspaper received its own copy of the song text—perhaps from the same committees of patriots in Boston or Newport. Lemay also notes a copy in the New-York Mercury for September 9, 1765, with a comment on its popularity: “The following Song has been sung thro’ the Streets of Newport and Boston.”

There is an account of two of the men, Martin Howard and Dr. Thomas Moffat, who were the “victims” of this hanging in effigy, as described in the New-Hampshire Gazette columns, in the Massachusetts Historical Society, Proceedings, lv (1921–1922), 236–237.

The text copy is from the New-Hampshire Gazette, September 6, 1765 (fig. 83).

tune: The tune intended for this text was composed by William Defesch and first published as “The Masquerade Song. Sung by Mr Beard, at the Jubilee Ball at Ranelagh,” in the Universal Magazine, v (London, 1749), 49. It became better known from its first line as “Ye medley of mortals” when it was used as a vehicle for comic and cynical songs of factional politics and social satire. As can be seen from figure 85, the original “Medley” is a general catalogue of fools, fops, and hypocrites. It was followed by a number of imitations: “Cox Heath Camp” dealing with militia encampments; “Connoisseur” satirizing wealthy esthetes; and Garrick’s “All in the wrong” dealing with people in theater circles.15

Simpson provides a copy of the tune (no. 431) and a listing of texts and sources, pp. 665–666.

The tune used here (fig. 84) was published in the Gentleman’s Magazine, xix (London, August 1749), 371 (fig. 85).

For A New Song, on the Repeal of the Stamp Act, Tune, A late worthy Old Lyon, see Smith, figures 164–165c and accompanying text.

Goody Bull or the Second Part of the Repeal. . . .

The World turned upside down,

or The Old Woman taught Wisdom

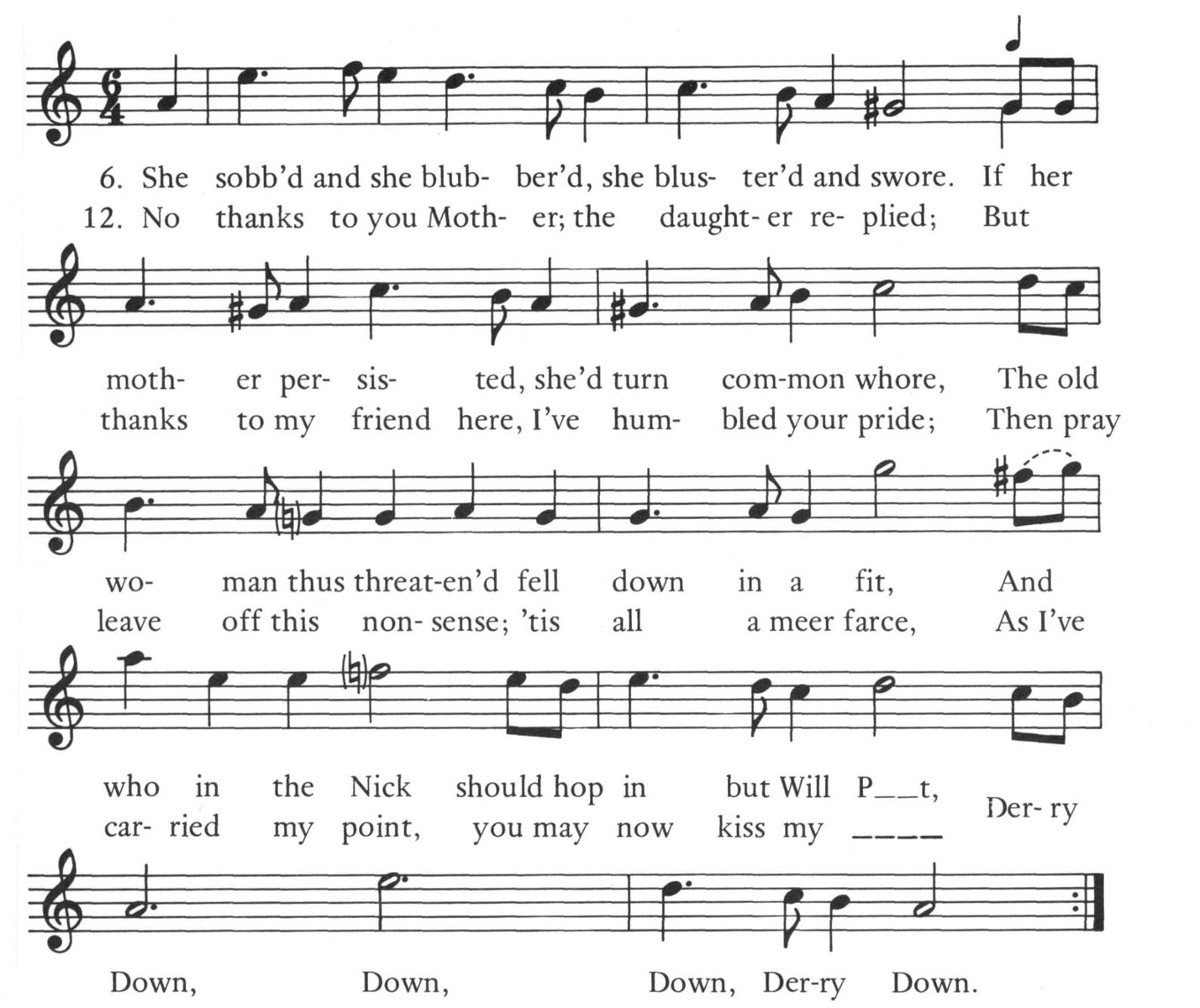

text: The writer has not found any American period printings of this song text, and only two period printings in England.16 It is not surprising that nineteenth-century anthologists censored it. But it is unfortunate that twentieth-century scholars have used the censored version since the venomous closing lines and the references to Pitt, such as verse 10, line 4, “You must surely be right if you’re guided by me,” strongly suggest the song was written by a conservative Tory who believed that Pitt’s arrogant leadership could bring only further humiliation for Great Britain at the hands of the crude and ungrateful Americans. Moore, page 32, quotes the anonymous author as saying, “it is an humble attempt to reconcile the parent and her children, made by a peacemaker to Great Britain and her Colonies.” The quote does not appear with the song text in the Gentleman’s Magazine, March 1766, page 140, which Moore mentions, nor in the caricature illustrated here. But wherever Moore found it, the quote has the right eighteenth-century sound, and it is a satirical comment in itself. The song was certainly not intended to promote reconciliation at home or with the colonies. It was part of the factional struggle in England.

There is a dubious story (based on a single third-hand account first published some forty years after Yorktown) that during the surrender ceremonies the British played a march called “The world turned upside down.” In recent years some historians have proposed that the song discussed here is the march referred to. The evidence against such an incident’s having occurred at all is lengthy and too complex to discuss here, but the main reasons why “Goody Bull” was not the Yorktown tune, if in fact there was one, can be summarized as follows:

- 1. The Goody Bull text had little circulation in print.

- 2. The “Derry down, etc.” at the verse ends of Goody Bull establishes the tune. The texts of the Gentleman’s Magazine copy and of the caricature agree on this refrain.

- 3. The “Derry down” tune is not in period fife books in spite of being a very popular English tune.

- 4. When a tune has more than one set of words there is no way to tell which title is implied simply from hearing an instrumental performance. “Derry down” had more than a hundred sets of words by the 1780s.

- 5. The “Derry down” tune was associated mainly with comic and even scatological texts. The British soldier’s attitude at Yorktown is reported by eyewitnesses as frustrated, angry, and humiliated. Such an attitude leaves little place for musical jokes, vulgar or otherwise.

For discussion of the caricature see British Museum, Department of Prints and Drawings, F. G. Stephens, Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, Division i: Political and Personal Satires, 11 vols. in 12 (London, 1870–1954), iv, 375–376, no. 4142. The text on the caricature has been used (fig. 86).

tune: Simpson’s tunes numbered 109–112 are variants for “Derry down,” some of which he dates back to 1700. He provides dozens of titles and sources for variant texts. Chappell provides a discussion and two complete texts with tunes in i, 348–351: “The king and the abbot” and “The cobbler’s end.”

The tune used here is printed in Calliope; or, the Musical Miscellany (London, 1788), pages 248–249 (fig. 87).

Address to the Ladies

text: If all the citations for copies of this song text in newspapers could be verified they would show that these verses were quite popular. But, of seven citations, there are three false leads, beginning with Moore, page 49. The verses are not in the Boston News-Letter for the year 1769 as Moore suggests, and as others repeat. Neither are they in the Massachusetts Gazette for the week including November 9, 1767, nor the New-York Gazette for April 25, 1768, as suggested by several modern writers. However, the New London Connecticut Gazette for November 20, 1767, does print it, minus the title, in the same basic form as the copy in the Boston Post-Boy for November 16, 1767, which has been adapted here (fig. 88). Moore’s copy includes four additional lines which look characteristic for the time but which seem anticlimactic and do not appear in the Connecticut Gazette or the Boston Post-Boy copies.

tune: No tune is indicated with either period copy of the text, but the title, the stanza form, and the giving of advice are all similar to Tom D’Urfey’s song “Advice to the ladies,” a comic description of some kinds of men no woman should marry. Simpson, pages 421–423, discusses the considerable popularity of the tune in the late seventeenth century, with titles and sources on some of its thirty-odd sets of words. The survival of the tune into the late eighteenth century was possible through its use in The Beggar’s Opera and six other ballad operas, plus its reprinting, with the original text, in D’Urfey’s Pills to Purge Melancholy. It is most easily accessible today in the 1959 reprint of Pills, ii, 8–14.17

The version used here is that in Pills (fig. 89); however, some of the phrasing and tied notes have been borrowed from another contemporary source for the tune, a single sheet folio entitled Ballad on the Battle of Audenarde, in the Marshall Collection, Houghton Library (fig. 90).

[Free America]

text: Originally known in other colonies as A New Massachusetts Liberty Song, this is more commonly known today as Free America and is attributed without documentation to Joseph Warren. Some writers have dated the song text to 1774, but Worthington C. Ford’s date of 1770 now seems conclusive.18 The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has a manuscript entitled Massachusetts Liberty Song Parodized, and the parody (a good one) is dated April 1770.19 Also, Shipton and Mooney date the broadside copy (Evans 42135), among the holdings of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, to 1770.20 Finally the Connecticut Courant reprinted it on May 8, 1775, but specifically noted that the song went back to February 17, 1770.

Dating this song is more than an academic exercise. Most Revolutionary War song texts show only minor variations of spelling, punctuation, and wording from newspaper to newspaper or broadside. But this text has an unusual number of variants, some of which seem to be calling for an independent America quite some time before it became fashionable to do so.

The text used here is from the Massachusetts Spy for May 26, 1774 (fig. 91). It still pays lip service to George III, “The Prince who rules by freedom’s laws in North America.” For other comments and a broadside version, see figures 172 and 173.

tune: The tune “British grenadiers” is indicated on most copies. Chappell, i, 149–153, provides a copy of the song with sources and the probable ancestor of the tune, “The London prentice.” “British grenadiers” seems to have been less popular as a vehicle for Revolutionary song texts than might be expected of such a stirring tune. The writer has found only three, one of which is the loyalist parody mentioned above.

An undated copy of the British Granadiers [sic] from the Marshall Collection is given (fig. 93), as well as the adaptation of this tune to the Massachusetts Spy text (fig. 92).

A New Song. To the plaintive tune of Hosier’s Ghost or [The Taxed Tea]

text: This seems to be the earliest response in the form of song to the Boston Tea Party, which occurred on December 16, 1773. The song text was published in the Pennsylvania Packet by January 3, 1774. It was reprinted January 27, 1774, in the Massachusetts Spy with credit to the Packet. The text resembles the first line of Hosier’s Ghost, and includes ghosts and other spirits, but is not otherwise a close imitation.

The text used is from the Massachusetts Spy (fig. 94). For other comments and a broadside version, see figures 182 and 183.

tune: The tune for Hosier’s Ghost acquired many names during a century of popularity from the 1730s to the 1830s. Once popular as “The sailor’s complaint,” by 1738 it had been adapted to “Welcome brother debtor,” a song describing life in debtor’s prisons (see also fig. 115 and fn. 31). (It is from The Prisoner’s Opera by Edward Ward [London, 1730], where the text was printed to a different tune.) In this form it was frequently reprinted through the 1820s in England and America and was parodied in several American loyalist songs during the Revolution.

Hosier’s Ghost was a factional ballad inveighing against alleged political intrigue during the “Jenkins’ Ear” controversy, which kept Admiral Hosier from easily capturing Portobello (near the Caribbean entrance to the present Panama Canal), though Admiral Vernon was permitted to do so with a smaller fleet and much resultant acclaim in November 1739. The ballad shows the bitterness caused by the death of Hosier and many of his crew from tropical diseases while waiting permission to attack. For the American colonists, the text of Hosier’s Ghost may have contained seeds of complaint about the operations of absentee government.

The last use of the tune as “The storm,” or “The tempest,” or “Cease rude Boreas” (first published ca. 1770) was perhaps its most popular form, since it appeared in twenty-four out of a sample of seventy-two American songsters published between 1787 and 1815 and was parodied in three political songs during the same period. The basic tune was ultimately more popular with the Tories and loyalists who used it for four songs to the rebels’ two. Chappell, ii, 597–598, provides further examples and information on the use of the tune.

Admiral Hosier’s Ghost from the Marshall Collection (fig. 96) is the source of the tune (fig. 95) to which the Massachusetts Spy text has been set.

The Irishman’s Epistle to the Officers and Troops at Boston

text: When the shooting began at Lexington, Massachusetts, writers for a time produced only laments and dirges and prose polemics on the American dead. Colonists at a distance saw some immediate humor in the precipitate British retreat and the subsequent siege of Boston. The Pennsylvania Magazine for May 1775 printed these excellent topical verses, which were reprinted by the Connecticut Gazette, June 30, 1775.

The Pennsylvania Magazine version has been adapted here (fig. 97).

tune: No tune is indicated for either period text, nor are there any tune hints within the verses. The author may not have considered it a song, since he left a stanza of four lines among three other stanzas of six lines each.

For a recording, The American Revolution through Its Songs and Ballads, Bill Bonyun adapted the verses to the tune of “The Irish wash woman.”21 With some reservations the adaptation has been retained because it fits the spirit of the text so well. Unfortunately, major adjustments had to be made to fit the text to late eighteenth-century versions of the tune. For example, bars 9, 10, 11, and 12 of the tune, as shown in the Spicer manuscript cited below, had to be omitted in our adaptation. Furthermore, though Chappell, i, 62–64, and Simpson, pages 165–166, show and discuss “Dargason,” a seventeenth-century ancestor of the tune, it doesn’t seem to become the “Irish wash woman” in form and title until the 1790s.

“The wash woman” has been adapted from “Ishmael Spicer’s Collection of Songs” (Chatham, [N.Y.], 1797), page 61 (fig. 98), a manuscript songbook in The Connecticut Historical Society.

The Yankie Doodles Intrenchments near Boston 1776

text: If the 1776 date is to be taken literally, this Tory caricature and verses were published before early April, since the Continental Army was in full possession of Boston by March 20, 1776. The author writes, “See Putnam that Commands in Chief Sir . . .” even though Israel Putnam commanded only the center division of the Continental troops besieging Boston after Washington took command on July 3, 1775.22

The caricature is discussed by M. Dorothy George in British Museum, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires, v, 218. The text to British Museum Caricatures number 5329, which is illustrated (fig. 99), has of course been adapted.

tune: There is no tune indication but one may assume that “Doodle doo” is intended rather than “Yankee Doodle,” as the chorus might suggest, partly because the words fit the former tune better, and partly because there are six other British Museum caricatures between 1762 and 1780 which have song texts to be sung to the tune “Doodle doo.”23 The Gentleman’s Magazine, April 1766, page 89, also includes a four-verse text with a “Doodle doo” refrain from Harlequin’s Invasion. Counting Yankie Doodles Intrenchments, The New Raree Shew illustrated here (fig. 101), and other Revolutionary War songs, there are a total of twelve texts to the tune, all in this same format.

Two of these are by American loyalists. Joseph Stansbury’s “The Campaign,” from the manuscript “Loyal Rhapsodies,” in the Library of Congress, is ambivalent.24 The first twelve verses could serve as a rebel song, but the emphasis shifts to loyalist satire in verses 19 to 23, and becomes conciliatory in the final verses, 24 to 27. The second loyalist song appeared as “A New Song to an old tune, written by a Yankee and sung to the tune of Doodle doo,” in Rivington’s Royal Gazette for November 27, 1779. Moore, pages 275–276, accurately reproduces this comic song text on the British capture of Savannah.

The final English (Whig) text, The New Raree Shew or a Touch on the Times, is engraved with the music shown here (fig. 101) and is sufficiently topical to aid in dating the text. Verse 8, “Next you see de Fleet of France-a / Lead de English Tars a dance-a,” refers to Admiral Keppel’s lackluster battle against the French fleet, July 27, 1778. Verse 9, Pondicherry was captured from the French in 1778 but “Could not make de English merry” until Keppel was “clear-a”; that is, until Admiral Keppel was cleared of charges of incompetency by the court-martial, early in 1779. Since the text does not mention that Keppel was forced out of active service in March 1779, we may assume the song was published about February 1779.

The New raree shew music from the Marshall Collection has been adapted to the British Museum caricature (fig. 100). This Houghton Library copy may be unique. No other copy of the music nor any further leads have been found.

Liberty Tree

text: Thomas Paine is generally credited with writing Liberty Tree, which was first published over the pseudonym “Atlanticus” in the Pennsylvania Magazine for July 1775. The loyalists of course had their own view of the Liberty Tree as a rebel symbol. Samuel Barney, in his pamphlet Songs of the Revolution (New Haven, 1893), page 35, tells of learning a song from a Union soldier who said he had learned it from his grandmother.

Yankee Doodle took a saw,

With a patriot’s devotion,

To trim the tree of liberty

According to his notion.

He set himself upon a limb,

Just like some other noodle,

He cut between the tree and him,

And down came Yankee Doodle.

Yankee Doodle broke his neck,

And every bone about him,

And then the tree of liberty

Did very well without him.

This Liberty Tree text is from the Massachusetts Spy for September 6, 1775 (fig. 102).

tune: The indicated tune, “Gods of the Greeks” (see discussion in the introduction above), was used for three other American songs in the Revolution: two rebel songs and one loyalist song by Joseph Stansbury in “Loyal Rhapsodies,” in which he deplored the dilatory tactics of Gen. Howe. “To the tune of Liberty Tree” was indicated for a number of patriotic post-Revolutionary song texts, but, since the original text acquired at least one more tune by the 1790s, there is a question about which tune is intended.

Fig. 104. A loyalist song text attributed to Capt. Smyth, from the Pennsylvania Ledger, January 7, 1778.

Marshall Collection copies of The Origin of English Liberty and Once the Gods of the Greeks have been used for this adaptation (fig. 103). It is listed in Schnapper, British Union-Catalogue of Early Music, ii, 744, under “Once,” but it is not in Chappell nor in Simpson.

A New Song, to the old Tune of “Black Joe” or [The Rebels]

text: The several variant texts of Black Joke are remarkably bawdy, but they have none of the bitterness of this loyalist text for which Moore, pages 196–199, supplied the title from “a ballad sheet.” We have not found the ballad sheet nor the source of Moore’s information that the verses were written by a Capt. Smyth.

This text is from the Pennsylvania Ledger for January 7, 1778 (fig. 104).

tune: The tune of the “Black joke” has a record of popularity as a song and as a tune from the 1720s to the twentieth century in the British Isles. From the 1730s to the 1770s, it was principally a vehicle for bawdy texts. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the text went through various transformations to emerge as the long-popular Sprig of Shilleah, and finally the whole song was submerged in treacle when Thomas Moore wrote his text Sublime was the Warning . . . for Irish parlor revolutionaries, and Sir John Stevenson smoothed out all the angularities of the tune variants. Neither Chappell nor Simpson has the tune.

The source for the tune version used here (fig. 105) is from a 1730 single sheet folio, The Coal Black Joke, British Museum, Music, g.315 #99. A copy from the 1720s entitled The Original black Joke sent from Dublin, in the Marshall Collection, has the same tune, slightly more ornamented, with a different but equally bawdy text.

The Halcyon Days of Old England: Or The Wisdom of Administration demonstrated: A Ballad. To the Tune of —Ye Medley of Mortals

text: Bitter reminders of internal divisions in this country over fighting a nasty war on another continent exist even today. This English Whig song from the London Evening Post was reprinted in the Connecticut Courant for June 9, 1778, and in the Massachusetts Spy for June 18, 1778. Moore, page 200, reports without amplification that the song text has been attributed to Arthur Lee. Although the verses are not a close imitation of those found in “The masquerade song,” or “Ye medley of mortals” (see fig. 85), the text uses similar techniques to satirize the stupidities and blunders of the war. A broadside from the 1750s in the Madden Collection, volume iv, number 6, at Cambridge University Library, is called Admiral Byng’s Complaint; To the Tune of Tantararara. It has the antiministry sting of Halcyon Days as it accuses the government of executing Byng as a scapegoat for the inadequacies of the navy and for its own unpreparedness at Minorca.

The text from the Massachusetts Spy for June 18, 1778, has been adapted (fig. 106).

tune: See notes above for [Burn All]. (Fig. 107.)

The King’s own Regulars; And their Triumphs over the Irregulars. A New Song, To the Tune of, An Old Courtier of the Queen’s . . .

text: The King’s own Regulars is worthy and characteristic of Benjamin Franklin to whom it has been attributed, though no one has yet proved that he wrote it. Granger, Political Satire, page 158, reviewed the evidence and found it unsubstantiated. The author of the text has imitated only the chorus and the chant form of the original.

The text as printed in the Boston Gazette for November 27, 1775, minus verses 2 through 11 which pertain to the French and Indian Wars, has been used (fig. 108).

tune: Simpson, pages 591–594, provides a thorough discussion of the tune and its text variations, some of which he believes may date back to the reign of James I. There is a remarkable Whig adaptation of the tune based on the “Tombs of Westminster” text, a comic song ca. 1700, in which Hogarthian London tourists are shown around the cathedral by a bored and droning guide. The Whig song text, from the Madden Collection, volume vi, number 1825, is ostensibly set in 1888, and has the guide showing the tombs and describing the unsuccessful careers of several British generals in America during the Revolution.

Most of the printed and engraved versions of the music use the tonic only for the first eight measures. A better version for singing is that from The Convivial Songster (London, ca. 1782), page 210, which has been freely adapted here to match the declamatory style (fig. 109). The original chant section in  has been reset in

has been reset in  the better to match the phrase ends and the rhythm of much of the text.

the better to match the phrase ends and the rhythm of much of the text.