INTRODUCTION: Imperial Odyssey

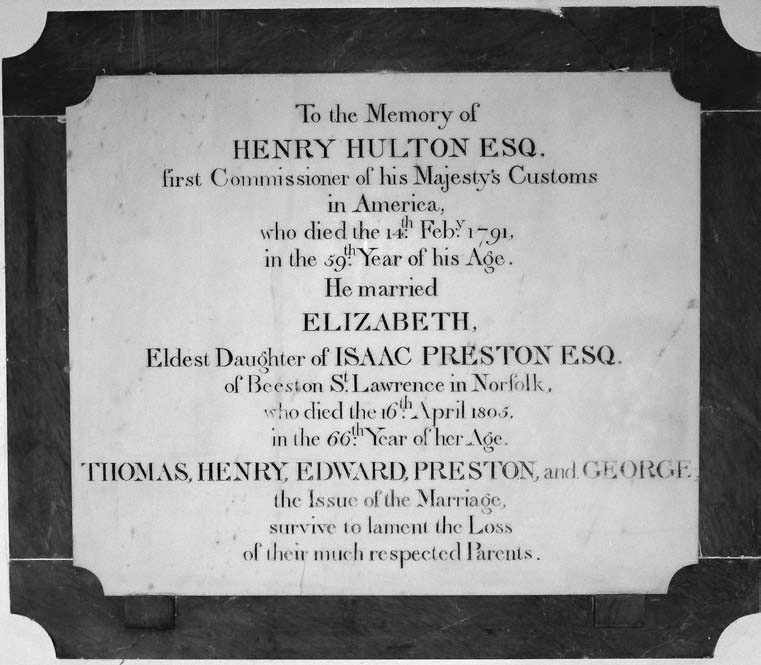

This tablet, dedicated to the memory of Henry and Elizabeth Hulton, is located in the west entrance lobby of St. Mary’s Church in Andover, Hampshire. The Hultons’ five sons intended it as a tribute to their loving parents. Originally placed in the old Norman era St. Mary’s Church built on this site, it was hung in the new St. Mary’s that replaced it in the 1840s. The dates for Henry are off. He actually died in his 60th year, on 12 February 1790. Photo by the author.

No other Odysseus will ever return to you.

That man and I are one, the man you see . . .

here after many hardships,

endless wanderings, after twenty years

I have come home to native ground at last.1

“I was no sooner arrived at those years, when it becomes expedient for every prudent person to think of his future establishment,” Henry Hulton wrote in one of his memoirs, “than I found I had to enter life without the support of friends, and under the disadvantages of a narrow fortune.”2 If those words held the attention of five readers and no one else, that would have been enough for Hulton; he penned them privately for his sons, not the general public. He did not pretend to have any insights that ought to be shared with the world beyond his family. He claimed no wisdom that should guide the founders of nations or builders of empire. He would have been content if his boys, the oldest of whom was still in his teens, found something in his life worth emulating, something in the “trials and difficulties, which he hath surmounted” that would “urge them to persevere with patience and fortitude, in the course of their duty”—an effort that he wished more parents would make for their children.3

Hulton did not set the opening scene of his autobiographical tale as pithily as Charles Dickens might have, but the point came through: he had not been born into a life of ease; he earned what he had. He wanted his sons to appreciate that they had been blessed with more advantages than he, so they ought to pay heed. He overcame adversity that they had been spared, but they would face challenges of their own and they must be able to rise to the occasion. He intended to show them how with vignettes from his own career.

It was advice that his own father, Edward, who died in April 1731, did not live long enough to offer. Henry had been born the preceding June, the youngest of five children, four boys and one girl. John, the firstborn, in 1720, had been followed by Samuel in 1722 and Edward in 1724. Ann was three-and-a-half years older than Henry.4 Their father died young. So did his middle child and namesake, who preceded him in death. The son of a glove maker to whom he had been apprenticed as a boy,5 the elder Edward Hulton had, at the time of his death, amassed a considerable estate for a tradesman. He owned buildings and land in and around Chester and, as was the custom, bequeathed the bulk of his property to his oldest son, John, after stipulating that his wife, Mary, be cared for out of the estate until her death. He left Samuel, the second oldest, some investment properties but nowhere near as much as he passed on to John. In addition to some personal effects, both Ann and Henry were given £400, ideally to be held in trust and earn interest until they each turned twenty-one. When necessary that money would “be Imploy’d for his & her Yearly Maintenance[,] Cloth[e]s[,] Education & Preferment in the World.”6

Innocent Abroad

What little we know about Hulton’s early life we learn only from Hulton himself. Of his childhood he said simply that his widowed mother—“pious,” “sensible” and, notably, “indulgent”—raised him to be virtuous and kind, presumably as a Presbyterian, though at some point he later became an Anglican. Having passed through what he called a “common course of education,” which most likely meant being taught by a private tutor with other boys of his age and station, he did not enter into an apprenticeship to learn a trade. Instead, as befitted his family’s improved status, he went to live with his older brother John, who had done well as a Liverpool merchant. There the boy was supposed to learn how to make his way in the world of men.

Henry did learn the basics of business but the counting house held limited appeal. His heart lay elsewhere. At age twenty-one, when he should have been ready to go out on his own, he was still undecided on his course in life. He “thirsted for enterprize, and adventure, and glowed with a desire” of doing something for his “own honor, and the service” of his country.7 Perhaps in seeking a middle point between pressing his youngest brother to be practical and not quashing his ambition, John Hulton devised a plan. Henry, backed by his brother, would set up an import/export firm in Hamburg with another young man from Liverpool, the son of Richard Gildart, past mayor and one of the town’s M.P.s.8 The young man’s older brother and John Hulton were friends; the Gildarts already had business connections in Hamburg.9

All seemed to be arranged when Henry sailed across the channel in June 1751 and awaited the arrival of his new partner, a passing acquaintance at best. Gildart never arrived. He decided not to go but it was February of the following year before Henry received a letter telling him that the deal had fallen through. By then Henry had lost whatever excitement he carried with him to the Continent. The French that he studied before leaving proved not to be quite the lingua franca he had expected and, under the circumstances, learning German came slowly. The British expatriates Henry lived among formed an ethnic enclave in Hamburg, diplomatically protected by extraterritoriality and exempt from local taxes or laws regulating religious services. Socially they kept to themselves.10 Hulton wanted to mix more freely among the locals so he moved farther inland, zigzagging from Zelle to Hanover to Brunswick, with his prospects no brighter.

His luck finally changed when he was befriended by a “little deformed Gentleman” named de Ruling, who struck up a conversation with him in English after observing him reading London newspapers in a coffeehouse.11 De Ruling, as it turned out, was very well connected, a native of Hanover with a post at the ducal court in Brunswick—a “dull town,” in Hulton’s view, no longer the thriving community it had once been under the Hanse.12 He and Hulton would remain friends until de Ruling died twenty years later. Hulton’s new contact opened doors that otherwise would have remained closed. Most importantly, de Ruling introduced Hulton to Johan Ludwig von Walmoden, at that time still a fifteen-year-old just beginning his studies at the University of Göttingen. Hulton now breathed rarified air: Walmoden was thought to be the illegitimate son of George II. Though the king never acknowledged him as such, neither was he expected to keep out of the public eye. His mother was the king’s longtime consort. Her grandmother may well have been the first mistress to George I.

Johan von Walmoden spent almost all of his time in Germany. His mother, by contrast, passed many of her days in London, with apartments at both Kensington Palace and St. James. She had met George II in Hanover in 1735 and Johan was born just a year later. All assumed that the king, not Walmoden’s husband, was the father. Walmoden knew of the liaison, accepted favors to look the other way and did not seek a divorce until 1740. By then George II’s queen, Caroline, had died, so Amelia Maria von Walmoden, nee von Wendt, was reborn as a naturalized subject of the British crown and elevated to the peerage as Countess of Yarmouth. She stayed with the king until his death in 1760. He supposedly forswore his other mistresses for her and the Countess became a fixture in the court, both in London and in Hanover. She was astute enough not to overplay her hand and even members of the cabinet, from the early period with Walpole to later years with Pitt and Newcastle, understood that she could be a useful ally and dangerous enemy.13

Hulton made a conscious choice about how he would try to get ahead when he importuned Walmoden for aid. Whatever air of naiveté he had about him that he wanted to preserve, it would have to be balanced with the skills of realpolitik and he would have to be a fast learner to have any chance of preferment. He could play, even be, the innocent at court, but that innocence could turn disingenuous with time—and Hulton was determined not to be a mere poseur. In his mind, at least, he succeeded.

When the king and Walmoden’s mother came to Hanover for a summer stay in the palace at Herrenhausen, Hulton moved to Hanover from Brunswick to be close by in case the opportunity arose where he could be introduced to the right person—which for him, Walmoden determined, was the Duke of Newcastle. Cabinet minister and master of political maneuver, Newcastle had become accustomed to being at the center of power. He and Hulton met; the Duke appeared approachable enough. Hulton “had frequent occasions of paying” his “respects to his Grace, who was always in a hurry, and put me off with general assurances.”14 Just turned twenty-two and still without solid prospects, Hulton understood that he had little to offer the Duke and that he was but one of countless supplicants trying to catch the great man’s attention. “I cannot urge any motives that may influence Your Grace’s regard,” he wrote in a necessarily obsequious note, “any further than by granting my request You will lay an infinite obligation on a gratefull heart.”15 But earnestness was not enough. The young Walmoden did not have much political stock and he was not going to risk it for Hulton when Newcastle became evasive. He advised Hulton to relocate to London and position himself for another run at the Duke when the court returned there in the fall, just before the opening of Parliament.

So October 1752 found Hulton in London. Newcastle promised nothing and did not appear inclined to give anything. He was cordial and yet artfully aloof, moving too quickly during this levee or that fete to grant Hulton a formal interview. Hulton went home to Liverpool the following spring, empty-handed, still with no clear future. For the next several years his life would revolve around the comings and goings of the royal court, which could move to Hanover in the summer and back to London in the Fall. In the reminiscences written for his sons he chose this as the lesson they ought to learn from his repeated frustrations:

In the course of my private life I have strug[g]led through many difficulties; and had occasion for a great deal of management and oeconomy, before I entered upon office. In publick business, I have had a life of combat, of labour, and lost; and through the whole have found very little of favor, protection, and support. Others, with my opportunities, might have improved them more to their worldly advantage; but I have the consolation to reflect, that I have passed thus far through the storm and have not made shipwreck of faith, and a good conscience, and I have a pleasure in a relation of these difficulties I have passed through, as the perusal of my story may be of benefit to my children, and animate them to persevere with fortitude, in their Christian course.16

There is suffering and then there is suffering. Hulton, after a year in Liverpool where he may have been content to live off his trust and his brother’s generosity, eased the pain of his disappointment by taking a shorter, cheaper version of the grand tour.17 After a quick trip to the Isle of Wight, then back to Liverpool, he and a friend set out on a more adventurous journey. They visited Blenheim Palace and passed through Oxford on their way to Paris and some extended sightseeing in France. Again Hulton’s preference for things English showed through. If the stiffness of upper-class Germans had bothered him, the smugness of lower-class French—their self-assuredness that it was good to be alive and even better to be French—galled more. Still, he could not help but be impressed by the “stout” French women who rowed him and his companion to shore from the ship that carried them across the channel, then hefted them onto their shoulders so that they would not get their feet wet when they landed.18

Hulton must have begun to wonder if he was jinxed: his traveling companion died from a fever brought on by a severe case of gout. Hulton buried his friend in Lyons—after bribing Catholic priests to inter a Protestant in their churchyard—and went back to London, hoping again to become part of the fall court.19 Once more he failed to win an appointment. He stayed on in London and tried yet again in the fall of 1755—doing what else, besides polishing his French and dusting off his Latin, it is hard to say.

At long last he succeeded, but only after “being kept in expectation for several months.”20 In January 1756 he learned that he had been appointed comptroller of customs at St. John’s, Antigua. It was not what he had hoped for but at least it was something. It did come with a catch: unlike some largely honorary posts, he would not be able to treat it as a sinecure, sharing the salary with someone else on site. He would have to go himself. He fell ill while preparing to leave, recovered, and made his way to Portsmouth to join a convoy sailing for the West Indies. His brother John accompanied him on the journey down from London “and this proved a final separation.”21

So after four-and-a-half years of delay Hulton had at last begun to quench his “thirst” for “enterprize and adventure.” Back at the beginning he had considered going to the West Indies and then decided against the journey—too far away, in a tropical clime that took many an Englishman to his grave. In the interim he had learned the importance of making the right connections and choosing the right moments to try to get ahead in a world where the few who were privileged over the many proceeded at their own pace, almost oblivious to those beneath them. He was never reduced to dire straits, never had to face the blunt truth expressed in aphorisms about beggars being choosers—because he never had to beg and he always had options from which to choose. But, having set his course on public service by court appointment, he could not afford to say no to anything reasonable just yet.

For someone who lectured his sons on the need for a good work ethic he did remarkably little work over these years. The men and women who took care of his daily needs may well have envied his, to their eyes, relaxed lifestyle. He no doubt saw it differently. It was easier to watch his social betters to see what they had that he still lacked, instead of glancing toward his social inferiors to see how little they had—an obliviousness to the plight of the poor that would not be cured by four years in the slave culture of Antigua. Like so many of his contemporaries in the master class he seemed to worry more about what slavery did to whites than to blacks. Hence his sympathy for the long-suffering wives of planters whose husbands fathered children among their slaves and yet pretended that nothing of the sort went on among them.22

Antigua, first settled by the English in 1632, is one of the Leeward Islands. Partly volcanic, partly coral in form, the island’s highest point is just over thirteen hundred feet above sea level. Virtually all of the trees had been cleared away long before Hulton arrived. There were no natural springs on the island: no tropical rain, no fresh water. Just over fifty miles in circumference, with only sixty or seventy thousand acres of arable land, Antigua could never surpass a Jamaica in commercial importance but it did come to rival a similarlysized Barbados in generating wealth. With well over half its land devoted to sugar production it turned a profit for the planters and therefore, again in theory, the empire. There were perhaps 35,000 people on the island, one in ten white, the other nine black, with some of mixed blood. Basically all of the blacks were slaves employed in the sugar industry—the raising and cutting of cane, refining of sugar, and processing of molasses and rum. There was a small but thriving merchant community and the island had its own legislative assembly. The compact town of St. John’s acted as the capital and the governor of all the Leewards—Nevis, Montserrat, St. Kitt’s, and other islands close by—resided there as well. At any given time there could be a couple of regiments of regulars stationed on the island and the Royal Navy used it as a port of call.23

It is very difficult to get a sense of Hulton as agent of empire on Antigua. As comptroller he was expected to work with the collector. Both were in turn expected to coordinate the activities of inspectors who worked the docks at St. John’s and Parham, the two ports for legitimate trade on the island. Having the comptroller and collector be one in the same, as was the case before Hulton’s arrival, increased the likelihood that corruption—never completely eliminated—could become too problematical. Smuggling was endemic in the sugar islands and potentially threatening to the British as the French began to exceed them in production. The French sugar makers could also sell at a lower price and for a variety of reasons, from more fertile soil to smaller, more efficiently-run plantations, to having greater diversification so that they were less dependent on imports of foodstuffs.24 Islanders, regardless of their imperial associations—Dutch, Spanish, French, British—routinely traded with each other.

Hulton had crossed over by convoy because the undeclared war that erupted between France and Britain in the forests of western Pennsylvania was about to become official. They feared they were going to be overtaken by French warships when they set out; they did not stop after making a landfall at Barbados for the same reason.25 France as enemy had suddenly become very real to Hulton. What might have been winked at in peacetime would no longer be tolerated during war. Hulton’s predecessor had spent more time lining his own pockets than in intercepting illicit goods. Even though Antigua’s assembly—after Hulton left—would condemn the practice of importing sugar and molasses from, say, French Dominica or St. Domingue, and labeling it as a product of Antigua for export to Britain and sale there or re-export to the continent, individual merchants might not comply unless watched. Illicit goods from the mainland North American colonies most likely became part of the island economy too, bringing Hulton into contact with New England merchants and giving him a foretaste of his later career in Boston. Those merchants preferred to be paid in cash for the flour and lumber they brought in so that they could spend it elsewhere. They did engage in legitimate trade and carried away large quantities of molasses that would be turned into rum back home, but they also filled their ships’ holds with cargoes obtained surreptitiously on Dutchand French-owned islands.26

What, exactly, Hulton did to crack down on smuggling is not very clear. How many hours he spent performing his duties is not clear either. On such a small island with such a small population, it might appear to have been a simple enough task. After all, St. John’s and Parham, with just five miles separating them, were a short horse ride or long walk apart. But then again a clever smuggler and conniving merchant could find ways to evade detection and an underground economy most certainly existed—but on how large a scale and at what expense to the mercantilistic empire cannot be known.27 London could not afford, either financially or politically, to be too obsessive about enforcement. Hulton may have been brought in from the outside as comptroller but the new collector was a local merchant; so much for guarding against a potential conflict of interests. Sending a full complement of officials to Antigua would have been cost prohibitive—again, politically as well as financially. Sometimes the enforcers of imperial rule turned a blind eye; sometimes they saw and punished. It was a dynamic that never changed.

The official correspondence for these years is sketchy; so is the personal. Hulton’s earliest surviving letter from Antigua was written very late in his four years on the island. It talked not of his duties but of his boredom, his feeling that he was wasting away in exile. “I would not wish any one who feels as I do, to experience what I have done,” he complained to a friend back in Liverpool. “I look back on past scenes wherein I was happy, but they will no more return; before me the prospect is dreary.”28

What he recorded later for his sons was for their character formation, not his retrospective view of the empire, so the focus was on individuals and their behaviors as object lessons. Some people were examples of what not to be, others were examples to be emulated. The dissipated and corrupt collector served as Hulton’s first bad example and he was followed by others. The good examples were those who lived in moderation—literally necessary for survival in the island’s climate, figuratively necessary for his sons in any social environment.

Hulton arrived with a cold from the voyage and developed a low-grade fever upon landing which lingered for months, but other than that he remained healthy. He developed his own regimen, up early in the morning and to bed early in the evening; exercise, including a morning ride, and frequent bathing; a large meal at midday with only a light supper at night, washed down with water more often than wine. He did not exhaust himself in too many social rounds with Antigua’s tiny circle of elites, fearing that those who danced and drank into the wee hours, exhausted and perspiring when they finally went to sleep, were inviting fever and then death. He kept up his reading—James Robertson’s history of Scotland and Edward Montagu’s survey of ancient republics were two recently published books that he mentioned—so that he could be a good conversationalist as well as intellectually engaged. Equally important, he learned to be a good listener, thereby ingratiating himself with the few men of letters on the island. “The attention of a young Disciple flatters their understandings,” he advised his sons, “and the conversation of such men, is the most easy and agreeable way that a young man can receive instruction.”29 He even composed a poem that he, with a close friend on the island, had published to help a widow in distress. The proceeds went toward supporting her household.30 Her story and that of the others fit into his overall didactic scheme.

You must not think my dear Children, that I mention any characters as a record of their crimes or misfortunes, but as a lesson to you: let your minds be ever impressed with a sacred regard to truth, in words, and actions, be assured, that without the practise of integrity, you cannot obtain the divine favour: that industry, prudence, and oeconomy, are necessary to worldly success, and to the enabling You to put your benevolent dispositions into practise. Vanity and ostentation will urge people to actions that have the semblance of virtue. They may be profuse without being generous; and hospitable, without benevolent affections. Such characters will be applauded by the vain, the dissipated, and luxurious; but the sensible and worthy part of mankind, who examine into the motives of actions, will bestow their approbation on the character, only as it appears to act conformably to truth in the circumstances in which it is placed, and the relation in which it stands to those around it.31

Hulton emphasized the need for a man to choose his friends and associates wisely, to keep his own counsel, to speak in confidence only to those of proven trust. He was astute enough to realize that by diagraming a formula for success he needed to show how it had worked in his own life if he were to have any credibility with his sons as they grew older. And so he did, writing his life story in fine luck and pluck fashion, using an autobiographical style later made famous by Benjamin Franklin.

The moral of Hulton’s Antigua tale unfolds chronologically: soon after arriving he made friends with a well-placed islander who would eventually smooth his way when he returned to London. The islander in question was Samuel Martin, wealthy planter and powerful politician. Speaker of the House in the Assembly, he stood at the center of Antigua’s social life. “He was a Gentleman of universal knowledge, of great politeness, and good manners,” Hulton informed his sons approvingly, “easy to live with, very communicative, and agreeably instructive, of strict morals, and a religious Man.”32 Martin too preferred water to wine and a good book to pointless conversation. He could be prickly and impatient but with Hulton he found a young man with the right values, the right comportment—with perhaps, on Hulton’s part, a dose of imitation serving as the sincerest form of flattery. Hulton spent many hours in the older man’s company. When he decided that he could stand it no more, that he had to get off an island that he apparently had left only for short jaunts to other spots in the Leewards, Hulton sailed for London armed with a letter of introduction from “Colonel” Martin to his son.

Knowing that the younger Martin was leery of officer seekers, the older Martin made his attachment to Hulton emphatic. Reading between the lines, he was cautioning his son not to make a virtue into a vice by becoming too fastidious, turning away all who sought his favor. Hulton “is indeed a truly good man,” Martin stressed, a devoted friend who had eased his aging and a dedicated public servant as comptroller. He wished Hulton had opportunities in the Indies more worthy of his talents. So highly did he think of him, he told his son, that if Britain took any nearby island from the French in the war then winding down he would do what he could to set him up with a prestigious office and a plantation of his own.33

The younger Martin had not lived on the island for any length of time since he was a boy. He had passed on to the Inner Temple after Cambridge and he sat in Parliament for Camelford, a borough in Cornwall. Connected to the Earl of Bute politically, he did not stand out in Commons; rather, he threw his energy into his post as secretary to the lords of the Treasury. Called by two later historians a “joyless man, solitary and self-centred,” he never married.34 Luckily for Hulton he was on good terms with his father and not apt to ignore his wishes, especially when Hulton’s appearance seemed so propitious. On his desk when Hulton called were stacks of paper dealing with logistical problems that the British Army had encountered while fighting on the Continent, including letters written mostly in German from suppliers there. “These are Packets of Papers and Letters,” sighed Martin, “that I have not been able to read.”35 Hulton offered to translate them and the next thing he knew he was back in Germany as part of a special commission to investigate fraud and corruption in the commissary—all of this without yet being released from his post on Antigua.

Fortune had just smiled on Hulton because he returned to London in October 1760 at an otherwise inopportune moment. George II died as Hulton arrived and consequently the Countess of Yarmouth and her son could have done little for him, even if they had been inclined to help. Hulton went to Newcastle first and received the usual noncommital response. His West Indian connection made all the difference. He was given another chance to prove himself, another shot at a better post and a new beginning.

He nonetheless trekked to Germany with some trepidation, fearing that failure there was very likely, which would end his hopes of rising any higher in government service. But then again, if he turned down the new post he would be expected to return to Antigua—a “dreary prospect”—and if he refused to do that, he might never be offered anything consequential again. “The heart grows callous and suspicious from frequent disappointments,” he lamented to a friend as he contemplated the choices before him, “and is unwilling to expose itself to fresh pain by connections that may only prove the disingenuity and ingratitude of human nature.”36

Hulton had been reluctant to recross the channel with good reason. He was about to spend two and a half very trying years on the Continent, arriving in April 1761 and not leaving until September 1763. He made sure that his sons knew how demanding the work was, but how important it had been that he stuck to it.37 “The business of my department was to examine, audit, and certify, all Accounts whatsoever of moneys due for forage, bread, Waggons, Trains, Hospitals &c.” It proved as draining on Hulton emotionally as it was on the commissariat materially. “Vain is the effort of the few, to withstand the torrent, or suppress the powerful iniquity” of the greedy and dishonest, he later lamented.38 His first day there a provisioner attempted to bribe him, gold in exchange for an army contract, as would others along the way.39 At least he enjoyed a friendly reunion with Walmoden, the onetime student now an officer in the Hanoverian army, and he was not expected to act alone in his investigations. He had clerks to assist in his duties and former excise official David Cuthbert joined him as a fellow commissioner, as did Sir James Cockburn for a time. Given the resentment of military men at having their actions reviewed by civilians in the field, two army officers, plus a cavalry escort, became part of the entourage—a valuable addition, decided Hulton. Cuthbert and Hulton trusted each other and worked closely together, trying to sort through past accounts while keeping an eye on new contracts. “These accounts were very voluminous, and it was as easy to build the Tower of Babel, as to settle them,” as Hulton put it.40 Their pay rate was a generous £3 per day, enough to live on quite comfortably, in good lodgings, with hearty food and servants to attend them. Even then they had money to spare. Their task could be quite tedious as they reviewed requests and receipts. It could also veer off into detective work, as they sent out clerks to check vouchers for stocks supposedly delivered with stocks actually received. They made few friends and many enemies among the local suppliers.41 They also had to be careful when dealing with army supply officers, urging them to be diligent without accusing them of corruption. “Oh! The curse of war,” sighed Hulton. Some men gained glory from it, others profited from it, “but the Nations are exhausted” and “the Subjects ruined” while “the Youth perish in the field” and “the aged and infirm are afflicted with “famine and disease.”42

Hulton became one of those who profited from the war, though in a different way. He and Cuthbert impressed men in government, including Newcastle, who was kept informed of what they were encountering in Germany. They continued until they were recalled in the summer of 1763. Investigations would drag on for years.43 Having reviewed accounts totaling roughly £1 million during his time in Germany, perhaps just a twentieth of the total spent, Hulton estimated that nearly one quarter—£245,000—had been disbursed to dishonest provisioners.44 Given the politics of the moment, marked by the difficulty of dealing with German contractors whose complaints in Hanover could prove troublesome in London, only a halfhearted attempt was ever made at restitution. Hulton and Cuthbert did not recover much money for the public account—just over £55,000—but they did put a check to fraudulent claims connected to past contracts and they may have made new frauds less likely.45 And, without really knowing it, Hulton had positioned himself perfectly for a much more attractive post, much closer to home.

Harried Servant

A new office of plantations clerk had been created under the customs board, a branch of the Treasury;46 Hulton seized the opportunity to fill it. Given the option of taking this post or returning to Germany, where he would work with Thomas Pownall, a rival when he had been a commissioner there, he opted to stay in London. “I did not chuse to be in any wise connected with Mr. Pownall,” he wrote when looking back.47 At long last he finally seemed to have the job he had dreamed of landing. His post was part of a new wave of imperial reform, not as ambitious as that attempted with the Dominion of New England in the 1680s but ambitious enough to cause a transatlantic disturbance.48

The chief financial officers of the kingdom, the lords of the Treasury, had started the imperial reform movement by complaining to the privy council, which in turn reported their complaints to the crown. With the king’s endorsement and with Parliament preparing to enact legislation for the king’s approval, all officials charged with enforcing the Navigation Acts were called to their posts, in anticipation of new laws and tighter enforcement, applicable to the entire empire but aimed at the mainland colonies of North America in particular. “We find, that the Revenue arising therefrom is very small and inconsiderable having in no degree increased with the Commerce of those Countries,” the Treasury lords reported to the Council, “and is not yet sufficient to defray a fourth Part of the Expence necessary for collecting it.” Moreover, they were convinced “that through Neglect, Connivance and Fraud” the revenue from those colonies “is impaired” and commerce “is diverted from its natural course,” making the “wise laws” behind the navigation system useless.49 In other words, smuggling ran so rampant that it mocked the mercantilistic notion that most trade ought to be confined within the empire.

Samuel Martin had left the Treasury but he continued to watch out for Hulton and helped him avoid being ordered back to Antigua. Technically speaking Hulton had been on an extended leave from his duties as comptroller there. He must have been flattered that the customs commissioners, upon nominating him, expressed “especial Trust & Confidence” in his “Ability[,] Care and Fidelity.” He secured his new post, which he would hold “at the king’s pleasure,”50 only after being interviewed by George Grenville, first lord of the Treasury, head of the ministry and enthusiastic champion of imperial reform. Word of Hulton’s efforts in Germany had reached Grenville’s ear. Grenville was for many years the bogeyman of American revolutionary history, as if he singlehandedly pushed through the program that caused an imperial crisis. He did not; something very much like it would have come anyway, with or without him. There was little opposition to the legislation that he shepherded through, the Stamp Act included, and there was no thought of using American revenue to pay off the national debt.51 Rather, Grenville, his king, and his parliamentary colleagues wanted to keep the debt from growing any larger and they expected Americans to help pay annual expenses on their side of the Atlantic that, from London’s perspective, benefited them as much as anyone else in the empire. The problem was that what appeared reasonable and fair in their eyes would be seen rather differently by colonists who understood that there were political as well as financial implications to Grenville’s program.

Grenville did not contrive a new theory of empire. The commercial regulations that marked his ministry were an extension of older laws going back a century, to 1663 and even earlier, when trade in the empire was legislatively channeled from one destination to another, in ships owned and sailed by subjects of the crown and citizens of the empire—just as Hakluyt had envisioned. Customs inspectors were patrolling colonial American docks as agents of the Treasury by the 1670s; vice-admiralty judges began hearing smuggling cases at nearly the same moment. But there had been very little that was systematic in these earlier manifestations of the navigation system. Grenville wanted new laws and stricter enforcement to bring practice more into line with theory. His timing was poor and his choice of taxes unwise. He miscalculated the economic and political fallout that his program would produce, but his brand of mercantilism was not malicious by intent.

Hulton, on the fringe of imperial regulation in Antigua, was now at the center. He worked out of the custom house on the north bank of the Thames, to the east of London bridge and west of the Tower, caught in the din of fishmongers, commercial agents, and river traffic. Seeking escape for his after-hours, he took up residence several miles away on George Street in Westminster. There, on the western edge of urban sprawl, his sister, Ann, came down from Chester to keep house for him. Unmarried and increasingly devoted to her younger brother, she was concerned that he had not recovered from the stress he endured on the continent and that he would soon be drained by new demands. “The task they have set him seems to be,” she wrote a friend back home, “after combating ye knaves in G[ermany], to find em in America and ye West Indies.”52

After spending a Christmas holiday with Ann in Bath, Henry set to the task before him, prodigious as it was. He was expected to coordinate communication between London and customs officials in North America and the West Indies, and was authorized “to lay his observations thereupon” before the customs commissioners, who could in turn pass them to the Treasury. It was a short step from the Treasury to other officials at Whitehall and parliamentary leaders at Westminster. But then the administrative apparatus was in such disarray that establishing a regular correspondence—and, in effect, instituting a bureaucratic chain of command—proved a formidable task, with letters passing back and forth over the breadth of the Atlantic sometimes taking six months to complete a circuit. Hulton did his best to routinize communications that were haphazard and reporting that was irregular.53 Historian Charles Andrews’s reflections on the navigation “system”—which was hardly systematic in nature—are worth remembering here:

England’s commercial policy was slow in the making; it never reached the stage of exact definition, even in the days of its greatest influence; and it can be understood only by a study of its principles in operation over a period of one hundred and fifty years. In its relation to the colonies in America, it was never an exact system, except in a few fundamental particulars. Rather it was a modus operandi for the purpose of meeting the needs of a growing and expanding state. It followed rather than directed commercial enterprise, and as the nation grew in stature it adapted itself to that nation’s changing needs.54

The challenges Hulton faced were compounded by other irritations: the job was not exactly what he thought it would be, the salary was reduced by a tax that he thought he should not have to pay, and the ministry pursued policies with which he disagreed. Hulton was miffed that he ended up as the plantations “clerk” rather than the plantations “secretary,” a change in designation that took place after he accepted the post. The customs commissioners decided to have only one secretary in their office, although Hulton as head “clerk” would have a staff of other clerks to assist him. Perhaps the commissioners did so at the urging of the existing secretary so that he, not Hulton, could continue to receive whatever legal fees were charged in connection with the office. Fees, as Hulton knew from his years on Antigua, were as crucial—and as controversial—to the navigation system as tax rates. Many of those who held their appointments through the customs commission subsisted on those fees, which, for the lowest paid—men far lower on the scale than Hulton—could bring in considerably more than their salaries, if they were paid any salary at all. Understandably, fees were yet another source of friction between the agents of empire and those they policed.

Worse, as Hulton discovered, his salary would be subject to the land tax even though it was paid through the customs commission. He had received £300 per year as comptroller on Antigua, a salary, boosted somewhat by fees, that had been treated as exempt from the land tax in England and local taxes on the island. Normally those in the customs service posted abroad did not pay domestic taxes because their offices were tied to revenue generated outside the kingdom. As Hulton saw it he fell into the same category, residence in England notwithstanding. His new annual salary of £500 would be reduced by £90 to cover the land tax. Since he would be working much harder at his new post than the old, in his view that meant he was actually working for less even though technically being paid more. Hulton protested to the Treasury for an exemption from the land tax. Despite securing a finding in his favor by the attorney general, it appears that the dispute lingered and the Treasury lords did not decide one way or the other before the post was eliminated.55

Nor was Hulton necessarily comfortable with the policies he was expected to help enforce. He did not disagree with Grenville’s desire to reform the system; just the opposite. He knew from firsthand experience that some Navigation Acts on the books were inadequate and should be replaced: thus he could see the need for the 1764 American Revenue Act, commonly called the Sugar Act, to replace the Molasses Act that had stood since 1733. In Hulton’s opinion that earlier act had been the unfortunate result of lobbying by West India planters. “Instead of operating as a fund of Revenue” it had become a “source of Smug[g]ling and corruption.” Those who were supposed to enforce the law actually acted in collusion with those who broke it, which “introduced a depravity of Morals, and alienated the Subjects from their duty to Government.”56 To the extent that the new law checked lawless behavior, it worked. But if Hulton ever had any enthusiasm for the Stamp Act as it wound its way through Parliament he lost it soon enough. His view of that act, as he looked back on it twenty years later, anticipated that of some later historians.

The Officers for the receipt of this Revenue were appointed, and the Ministry were pleased with the prospect of a considerable aid, by means of this new duty. But the first object of establishing authority, and respect to government had been neglected. Ignorant of the State of the Colonies, they rushed into a measure which from the Constitutions of the several Governments, they could not support against the clamours, and opposition of the people. The consequence is well known. From this time a spirit of resistance was adopted in America against all Revenue Laws; and the authority of Parliament, which at first was questioned, became to be in general denied; and any means to avoid, or prevent the execution of those Laws, was deemed right.57

However skeptical Hulton may have been about the Stamp Act at the moment it became law, he did not make his doubts public. He went about his job, sending out dispatches from his superiors and gathering responses from the colonies as they trickled back to London. If he offered advice on policy to the ministers at Treasury or subministers in customs, he did so guardedly, veteran as he had become of court politics. Knowing when to speak and when to hold his tongue was by now second nature.

Natural as his circumspection was then about imperial politics, it is somewhat odd that Hulton wrote so little later for his sons about the most important personal decision he made during these years, stating simply: “In the month of Sept. 1766 I was married to your Mother, at which time I was confident my Establishment would continue in London.”58 Perhaps he considered it unseemly to talk of how such matches are made; perhaps he thought the boys would know what it meant to marry well if they followed his advice in other areas; perhaps he thought it too obvious to require explanation, since she as much as he raised them. In any event it had been a most fortunate day for Henry Hulton when he met Elizabeth Preston, his future wife and the boys’ future mother. She proved to be a true partner in life, sharing his ideals, standing by him in his trials, raising five sons in circumstances quite different from those of her own more sedate childhood. Eight years younger than Henry, she was the daughter of Isaac Preston, a country gentleman in Norfolk. Preston also owned a townhouse in London; presumably Henry and Elizabeth met when she was in the city, at one social gathering or another. It is not too difficult to imagine an occasion where their paths might have crossed. They would have seemed a likely match: he a decent godfearing fellow with a well-paying government job, she the daughter of a wealthy man who could bring some money as well as a good name with her. They moved to Gerrard Street in Soho, closer to the city center but still in Westminster, not far from Covent Garden.

Elizabeth, like her new husband, probably expected to live a comfortable life in greater London. That was not to be. In just over a year Henry would end one job and begin another—over three thousand miles away. Hulton recognized he was asking much of her when he reluctantly accepted another post, a post requiring them to traverse the Atlantic for North America. “It was very severe to me to be compelled to remove to a remote part of the World,” he reminisced, “and to occasion her to withdraw herself from all her friends,” and, he might have added, to be informed of this when she was pregnant with their first child.59

Hulton may have felt that he had no choice. His position as plantations clerk was about to be eliminated after four years, in yet another wave of imperial reform. The prime mover this time around was Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer in a ministry headed nominally by William Pitt, now Earl of Chatham. Though a crown appointee rather than a true civil servant and therefore serving at the king’s pleasure, Hulton, like other bureaucrats, could expect to keep his job if he did it well and did not offend the wrong people. He had held onto his clerkship through Grenville’s ministry, then Rockingham’s, and was continuing on as Pitt’s got underway. But with Pitt incapacitated, Townshend became the dominant force in the ministry, and he was determined to bring his own brand of reform. That included terminating Hulton’s old job, though not because of anything that Hulton himself had done or failed to do. Townshend had met Hulton; he talked with him about reforms that he and like-minded parliamentary colleagues had mulled over. As Hulton recalled it, Townshend

sent for me, and told me of their intention and desired I would consider what goods it might be proper to lay a duty on in America. I answered him, Sir, before you lay any fresh duties in America, it might be best to see those well collected that are already laid. Why, are they not says he[?] No Sir, the Duties on Sugar, Wines, and Molasses, are not. Well, says he, we shall appoint a Board of Commissioners, and more Officers to see to the better management of the Revenue in that Country.60

The next thing Hulton knew the office of plantations clerk had been closed, a new American Board of Customs had been formed in its place, and he was one of five men named to it. He did not seek or even want the post. It would be at the same salary as the one eliminated and he would have to relocate his new family across the ocean in a strange land, an expensive proposition taking him into a potential minefield. His new post would be paired with a spate of new taxes that could be counted upon to irritate the very people he was being sent to live among.61 None of this boded well. Hulton would have preferred to stay in London but, once again, he was confronted with the reality of his career choice: even after all these years he could not afford, financially or politically, to say no if he had no better prospects—and he did not have them.

The new American-based board had actually been suggested by the customs commission itself, perhaps at Townshend’s instigation, even though that meant surrendering some of its own power.62 The new board would answer directly to the lords of the Treasury. The London-based commissioners were willing to give up some of their power because they decided that the colonies were too far away for them to manage effectively, particularly since there was so much resistance to the Navigation Acts and so many problems within the customs service itself. The new board, acting on site, would, they thought, be able to keep a closer eye on both trade and trade enforcement, weeding out the corrupt from within their own ranks and bolstering those who tried to be diligent in performing their duties.63 After virtually no debate Parliament passed a bill in June 1767 enabling the king to form the new board and appoint men to it. A badly fragmented opposition saw no opportunity to rouse the public or stop Townshend—as would be the case with virtually everything Townshend hoped to carry into law.64

The original report did not designate a place for the commissioners to take up residence. By the time that the American board was formally created—on 14 September 1767—Boston had been decided upon. That in itself was a signal that great change was intended, that Whitehall had effectively thrown down the gauntlet and taken up the challenge for a contest between imperial authority and provincial autonomy at the very heart of resistance to the navigation system.65 Hulton was named first in the commission, which perhaps in some informal, purely honorary sense made him senior to the others, but he was not designated the commission’s chair. The chair would end up as a rotating position; all five members took turns occupying it. Whoever acted as chair did so for procedural purposes only. There were no special powers, no heavier voting weight assigned to the office. “We do hereby give unto you or any three of you,” the Treasury lords informed the new commissioners, “full Power and Authority to manage, direct and cause to be levied and collected” all of the duties on any goods carried to or from the mainland colonies of North America, plus Bermuda and the Bahamas.66 The West Indies remained under the London board’s jurisdiction. All other officers holding king’s commissions in the colonies, both civil and military, were instructed to cooperate with the board. Although board members were not expected to do actual inspections themselves, they had a general warrant to search any vessel within their jurisdiction, day or night, and all dock facilities during daylight hours. More importantly, they also had authority to hire and fire other customs officials based in the colonies, and to use revenue generated by the Navigation Acts to pay salaries and other expenses.

Heretofore the men of the customs service had been unable to keep revenue ahead of costs. Annual overhead, mostly in the form of salaries, accounted for more than monies collected. The vast majority of men on the payroll were from the colonies, not the mother country. They virtually monopolized the lower paid posts. The full panoply of officials in Boston before the commission’s creation—comptroller and collector, surveyor and searchers, weighers and gaugers, landwaiters and tidesmen—had accounted for roughly £1000 annually in salaries. Creation of the new board better than trebled those costs. The commissioners alone added £2500 to the total for the Boston area, and close to another £1000 was allocated for a secretary, a cashier, clerks for both of them, and two inspectors general. Then there was the solicitor and his clerks, who accounted for another £200 or so.67 New Englanders already resentful of the imperial tax collectors in their midst bristled at the seeming profusion of new costs and new posts. The expectation that duties would be paid in pounds sterling rather than paper money or by some other means proved just one of many irritants to merchants throughout the colonies.68 It was not the amount in fees that mattered most—a mere pittance, compared with the hundreds of thousands spent annually to maintain troops in the colonies and pay the salaries of other royal appointees, the hundreds of thousands in lost revenue due to smuggling, and the millions generated in trade overall.69 The disgruntled would complain that the primary motive in enforcing the laws was to fill the pockets of bureaucrats while reminding colonists that what they considered rights were, in London’s eyes, privileges. That John Robinson, the collector for Rhode Island, was named one of the five commissioners only added to the resentment. It seemed that London had deliberately chosen someone who was alienated from the local population.70

Robinson was already in Boston when the board was formed; so was John Temple, one of the other board members. Robinson hailed from England and Temple, though Bostonborn, had spent years in the mother country trying to position himself in society through family ties to the Grenvilles. Hulton made the voyage across with the remaining two appointees, William Burch, a fellow Englishman, and Charles Paxton, a Massachusetts man then in London.71 As plantations clerk Hulton had had dealings with all but Burch, either in person or by mail, because all three were already involved in the navigation system.72 Those dealings should have warned him that trouble lay ahead. Paxton, an ambitious customs officer based in Boston, had become close to Francis Bernard, the royal governor. Zealous in his quest to catch smugglers, to many merchants his actions were anathema. They felt that his primary motive was to become wealthy at their expense. That he had lived for so long in Boston added insult to injury.73 Temple, who had been surveyor general of the customs in the northern colonies since 1761, loathed both Paxton and Bernard. Not only that; he thought the new board a mistake, despite his being appointed to it. He preferred things as they had been before and saw no logic to the elimination of his old post. Therefore he took an almost perverse joy in the board’s many failures. Looking back, “I little thought at that time that Mr. Temple was the fomenter of resistance to the authority of Government, and persecution of its Officers, which he afterwards proved to be,” Hulton lamented to his sons.74

Hulton’s complaints about Temple were proof enough that problems came as much from within the customs service as from without, from the board itself as well as subordinate customs officials unhappy with new rules and new faces. “‘Tis said, these Commissioners, are resolved to make all the Officers do their Duty Strictly” because “New Brooms sweep clean” complained a New Yorker not looking forward to change.75 But he need not have worried. The new board did not bring with it a new way of doing the king’s business and it is not very helpful to dismiss the board as an egregious instance of “customs rackateering”—the charge leveled by a later American historian, Oliver Dickerson. Perhaps without his realizing it, American protestors had posthumously converted him to their cause. In Dickerson’s depiction the empire, as exemplified by Townshend’s program, had become the captive of a spoils system, with emphasis shifting from the regulation of commerce to the generation of revenue, revenue intended to enrich corrupt individuals rather than benefit the larger community. The navigation system, once the “cement of empire,” Dickerson concluded, had been shattered by men who replaced a benign mercantilism with a poisonous form of imperialism—foolishly and shortsightedly by some, with malice aforethought by others. Ironically, they pursued commercial policies that were anti-commercial at their core.76

But malice is difficult to find among the men at Whitehall and Westminster who formulated American policy in the 1760s. Foolishness is easier to spot, but it was foolishness in trying to better manage something old rather than in attempting to try something new. There was never a clear dividing line between the desire to regulate trade and the desire to raise revenue. Both impulses were present from the beginning.77 And those elements of Townshend’s program considered dangerously innovative—restructuring the viceadmiralty court system, new duties on items such as tea, or creating a civil list of imperial officials to free them from provincial control—were intended to fix problems in the old apparatus, not erect a new one. Protesting Americans often claimed that they simply wanted to return to the days before Grenville and Townshend, to the empire they had known and loved.78 But that was because the old rules had not been enforced. If enforced they would have been deemed as unacceptable as the new ones.

And yet modern scholarship has shown that the idea of a reciprocal empire, where mother country and colonies would each benefit from the relationship, was not so skewed after all. The colonial economy had grown at an even faster pace than that of England. For some sectors of the economy that growth was despite membership in the empire; for others it was only because of it.79 At the same time, it is equally true that the colonists responded to reality as they perceived it at the moment, not reality as a later generation of historians might construct it.80 To a growing number of them, especially those in and around Boston when Henry Hulton arrived on the scene, the navigation system seemed to be oppressive and Parliament appeared increasingly tyrannical. Hulton’s presence as a member of the new American Board of Customs only reinforced those impressions, as criticism escalated and political opponents were demonized.81

Even Hulton’s high salary grated on some nerves, as did other perquisites to the job. As a case in point, Hulton was made “principal deputy receiver” for the Greenwich hospital tax in June 1768. With that he became a multiple officeholder and therefore susceptible to the sort of criticism directed repeatedly at lieutenant governor cum chief justice Thomas Hutchinson. The tax was used to support a hospital in Greenwich, England, for sick or injured seamen. Part of the funding came from a six pence per month tax on seamen’s salaries, a rate set by Parliament in 1696 and applied to the colonies since 1729. Hulton did not go out to collect the tax himself; rather, he paid others in the customs service to do it for him at fifty-two colonial ports, from Georgia to New Hampshire, from Quebec to Nova Scotia. He was allowed a 10% commission on all funds collected, which in a good year could bring him over £200—a tidy sum.82 The receiver, Thomas Hicks, who lived in London, took his cut as well.

Not surprisingly, seamen in the colonies did not like paying the tax or dealing with those officials who collected it. Wages routinely went underreported or were not reported at all. Some fishermen—notably in Marblehead and Salem—refused to pay altogether, contending that they were not sailors in the sense intended by Parliament. When the board replaced the collector for the port of Salem, in part because he was not collecting the tax, the press cried foul, complaining that it was a tax on a hospital local sailors would never use and it was being pushed by a man who profited directly from its collection.83

For aggrieved colonists the hospital tax was yet another example of imperial reaching into provincial pockets. Navigation acts—the sole focus of most historical studies—came and went; fees were a constant. They were split among various officials, commonly the collector, comptroller, and lesser officials, by task. They added a profit incentive to enforcement only slightly less irritating to local merchants than similar practices—and for considerably more money—used in the vice-admiralty system.84 Vessels were charged to clear ports on arrival and departure. Taken individually these charges did not amount to much money, often less than a shilling, perhaps just a few pence.85 But not only did fees have to be paid; bills of lading had to be presented, bonds posted, and certificates issued, all of it a bother to those wanting to set sail or drop anchor and unload. Rates were not fixed by Parliament, the Treasury, the customs commission in London or even necessarily the American board; local collectors routinely set their own. Not only did local merchants and shipowners complain; so did royal officials who felt that their own authority was being circumvented. A furious Governor Guy Carleton of Quebec informed the board that he would have none of such practices. When the collector there changed the fee schedule without consulting him, he exploded, “I only comply with the will of the King, our master.” He would not “suffer Acts of Parliament to be confounded with the Mercinary Iniquity of Men in Office.”86

Disputes within the imperial ranks could cut even closer than royal governors versus customs officials. Hulton had had glimpses of divisions within the customs service when he was plantations clerk. Yet another of the ironies of what followed once he arrived in Boston is that he and John Temple, their many disagreements notwithstanding, could agree on one thing: when possible, it is better to soothe than to offend. All the same it was impossible to please everyone, although Hulton apparently tried to do just that. Thomas Hutchinson, for one, thought him just the man for a difficult job. Upon meeting Hulton after his arrival in Boston, Hutchinson described him as “sensible” and prudent” and as “well calculated for the post at the present times as can be.”87

Perhaps Hulton’s attempts to placate all parties made it impossible for him to get along with a strong-willed, unforgiving man like Temple, who was determined to clear opponents from his path. Hulton would not—could not, really—take Temple’s side in his longrunning dispute with Governor Bernard. The customs commissioners and Treasury lords, had they paid attention, would have seen that, if they were going to name Temple to the new board, they ought to send Bernard elsewhere. There was bad blood between them; they would not work together as agents of empire. Temple had been trying to get Bernard removed since 1764, alleging that he was corrupt, that he and a minor customs official were guilty of profiteering and blackmail. Temple succeeded in getting the minor official fired; Bernard was another matter.88 And all of the talk in London of reform notwithstanding, the commissioners went forth with no clear connection to Bernard and other imperial officials outside of the customs service. Their powers were independent of Bernard’s and his of theirs—which weakened both.89

Bernard refused to be cowed and held onto the governor’s chair, even though he knew that his power was ebbing. He would have been happy to leave the Bay Colony—but not until he had a post equal to his ambition. In private he urged bold imperial reform. In public he was more timid. Hulton found his ideas appealing and was convinced that, had London listened, things might have gone differently. Whether Bernard was on the right reform track is now moot. He was scarcely able to save himself. Having arrived in Massachusetts after serving as governor of New Jersey, initially Bernard, an Englishman, had gotten on well with the various political factions in the province. By the onset of the Stamp Act crisis five years later he had become increasingly marginalized. His own councillors voted consistently against him and sided with the lower house of the assembly when disputes arose pitting executive against legislative power. Those councillors were chosen by the house, not the governor, not the crown. Bernard had the authority to prorogue a legislative session. He could even dissolve the assembly and call for an election before reconvening it. But exercising his authority could cost him his power, so he had to proceed carefully.

Town politics compounded his problems.90 Boston was essentially self-governing, virtually autonomous from provincial or imperial control. Bernard, more than anyone else in the colonies at the time that Hulton crossed the Atlantic, gave credence to the charge that Massachusetts was becoming ungovernable because Boston was a law unto itself. Until Boston was controlled, he warned repeatedly, no imperial official could do the king’s bidding or uphold acts of Parliament.91 The town’s sixteen thousand people were crowded onto a narrow peninsula that could be a bustling, jostling place—the east side of which was crammed with docks, wharves, warehouses and shops. The town meeting ran the town, with freemen voting for those who would represent them in the lower house, various town officers, and, most importantly, the selectmen who acted as an executive committee on town business. Many of those who rose to power in the province did so first through the town, Samuel Adams foremost among them. Political caucuses like the Loyal Nine and political action groups like the Sons of Liberty played a role in shaping Revolutionary America, but none rivaled the town meeting in importance. Imperial officials found that fact difficult to accept and yet they made no significant attempt to change it until 1774. By then it was far too late.92

Hulton may well have wondered if it was not already too late when he came ashore on the morning of 5 November 1767, his ship having dropped anchor in Boston harbor the night before. He had said his goodbye to Elizabeth just as she was regaining her strength from the birth of Thomas. She would join him the following June, with Thomas, a servant or two, and with Henry’s sister, Ann, who lived with them for virtually the entire time they were in Massachusetts. To Ann fell many of the duties of running a household once Henry purchased a farm in Brookline. She had stayed with the family in town for nearly a year before then, in their rented house. If Henry had been able to purchase something in Boston proper he might never have gone into the countryside. He was only able to purchase the farm through a third party. Had he made the offer himself, he might have been rebuffed, as he was in Boston whenever he tried to buy real estate there.93 Both he and Burch had found that the longer they were in town, the more difficult it was for them to secure lodging, so Burch went out to Dorchester while Hulton settled in Brookline.

For once disappointment in one setting had brought opportunity in another. As in London, Hulton was able to set up a household removed from the hustle and bustle of city life. According to Ann, “My Brother lives on a spot of Earth which he calls his own,” one so satisfying to him and Elizabeth “that they would not chus to change it for any other spot in New England.”94 Henry’s preferred schedule was to work four days a week in Boston and remain on his farm the other three, where he puttered about, seeing to his orchards and livestock, spending time with Elizabeth, and watching his family grow. It was already a prized property when he bought it, with thirty acres, a two-story house and outbuildings put on the market by Jeremiah Gridley’s family when Gridley died. Hulton added a greenhouse, a new barn, and planted saplings so that eventually he had around eight hundred apple trees. “I could not conceive a domestic Situation in this Country where I could be happier than I am at present,” he wrote to a friend back in England, in seeming contentment. “We are indeed out of the World of business, of politics, and pleasure, but we have a World of happiness within ourselves.”95

Henry and Elizabeth brought three more sons into the world during their Massachusetts years: Henry, born in Boston in May 1769, with Edward and Preston following in October 1771 and October 1773, both at the house in Brookline.96 When Edward was just under a year old he and his brothers were left in the care of their aunt Ann and the household servants while their parents embarked on an exciting adventure. They traversed nearly fourteen hundred miles of sometimes rugged country in eight weeks, better than eight hundred miles by land, another five hundred plus over water, all the way to Quebec and back. They set out from Brookline on 26 August 1772. Accompanied only by their driver and one other servant, they traveled the breadth of Massachusetts by two-horse coach, through towns that rarely—in some instances, never—saw carriages on their dusty, rutted roads. After crossing into New York and reaching Albany they headed north, crossing and recrossing the Hudson until they reached Fort Edward, just below Lake George. They went on a bateau—crewed by others—the length of Lake George into Lake Champlain, on into the Richelieu River to the St. Lawrence, then to Montreal. They sailed by ship to Quebec. When they left Quebec for the return journey they sometimes traveled by land in a post chaise, by water in a canoe, then back down the lakes, again by bateau, to Fort Edward. Picking up their own horses and carriage, they went by a different route to try to avoid some of the more broken terrain in eastern New York and western Massachusetts. In that they largely failed, but they were back safely in Brookline on October 20th.97

Although finding food and shelter suitable to their tastes was a challenge the entire trip, they never went without. The most they roughed it was a four-day period passing back down Lake George, where once they had to put ashore and sleep in a tent made from the batteau’s sail, eating cold food, shivering through an even colder rain, not changing their clothes for days on end. They were never in any particular danger except those inherent to such travels—real enough, and Henry was rightly impressed with Elizabeth’s fortitude. She “supported all her difficulties with great spirit,” he reported proudly.98

Much of what he saw pleased him—the land more than the people. “It is amazing how rapidly the back parts of this Country are settling, and with what little means of living people sit down in the inhospitable woods,” he marveled.99 He did not think Canadians took advantage of what nature provided them. Fertile soil was not put to good use because the people, descendants of a French peasant culture, lacked the industriousness of British colonists to their south. “The people,” he observed with a bit of disdain, were “very lazy and dirty yet very chearful and happy.”100 He seemed to think that they were not yet worthy of the opportunities bestowed on them by incorporation within the British empire. That he was proud to be part of that empire was evident in his choice of places to visit. As a board member he could have gone north purely for imperial affairs, to consult with customs officials stationed in Quebec—and indeed he did stay in the upper town as a guest of the port’s collector. But there was much more to the trip than the adventurous or business sides to it. It was a pilgrimage, a trek to an imperial shrine. Twice Hulton stood atop the cliffs where British soldiers had picked their way up in the dead of night, making possible Wolfe’s great 1759 victory outside the walls of Quebec. He strolled the Plains of Abraham, site of the decisive battle where Wolfe died leading his men to glory, a place now “remarkable”—sacred ground of empire that caused him to scribble a poem to Wolfe’s memory, on the spot.101

Hulton’s pride as an Englishman, his pride as servant of the crown and agent of empire, would color his view of all things American, whether in Canada or Massachusetts. There were those moments when he could see himself as both English and American, and believe that he had found a new home within the same expansive imperial community. “I Bless God my family have been and are well and enjoy every blessing this can afford,” he wrote in one of his more peaceful moments at Brookline.102 At those private interludes to his public life he expressed no desire to ever leave. “I now have three Boys,” he wrote a friend in England, “and from any thing I can yet see it is probable that I, and my family after me, will remain in these parts.”103 But there was something about American attitudes that bothered him, an inappropriate pride in place. The irritation burst through in a letter to Elizabeth’s brother, who had just returned from his own grand tour of the Continent.

You have seen the World in the polished, we, in its rude State. You have gone over the Boasted remains of Antiquity, and observed the Conscious pride of those who demand respect from the lustre of their descent, and glory in what they have been. We have seen the face of nature as it was left at the flood; uncleared, and uncultivated and mankind in a state of equality. But tho’ we cannot glory in heroic actions or claim the honours of an illustrious Ancestry, yet do not think that we are without an imaginary superiority, that we do not pride ourselves in the possession of advantages over others. Happy delusion! Where are the people, or where is the mortal, that has not a little fund of this self-flattery? That cannot place himself in some point of view, where he can look down upon others? This gratification to pride, is a most comfortable cordial, and makes the wretched support many evils—but what say you, is your boast? Why we boast a glorious Independency. We look on the rest of the World as Slaves, and despise titles, and honour. And as we cannot glory in what we have been we pride ourselves in what we shall be. The little island of Great Britain is a small inconsiderable spot. We shall be the Empire of the World, and give Law to the nations.104

When Hulton wrote “we” he really meant “they.” He did not share their boosterish self-confidence that they were destined to lead, that even the mother country herself ought to—and someday would—bow before them. Although he could appreciate the raw energy so evident in Massachusetts he was more ambivalent about the lack of polish he saw there: on the one hand, he found the honesty and directness of many people refreshing; on the other, he wished for some happy medium between the artfulness of self-styled sophisticates and the artlessness of the common sort. And it was the common sort, with the complicity of their social betters, who made his life as a customs commissioner so miserable. Inability to do the job he was sent to do gnawed at him, causing anxieties that he had never felt on Antigua. Although those anxieties did not match what he had experienced in Germany,105 “a sense of duty, inclination, and zeal for the service, will carry men a great way,” an exasperated Hulton complained to the Treasury, “but the best kept minds will be damped by a long endurance of persecution from their enemies, and neglect from their friends.”106

Hulton’s short trips around southern New England and long excursion into Canada were also an escape from the cares, even the dangers, of office. All of the commissioners but Temple felt the pressure. John Robinson had had to look over his shoulder even before he was named to the board.107 Hulton, Burch, and Paxton had been threatened with abuse from the day of their arrival in town—inauspiciously, on the annual Pope’s Day where Boston was the scene of rowdy merrymaking. Hulton had actually spent his first night ashore under John Temple’s roof and shrugged off the taunts as nothing serious. He tried that approach any number of times, hoping that would ease the tension. Sometimes it worked; more often it did not.

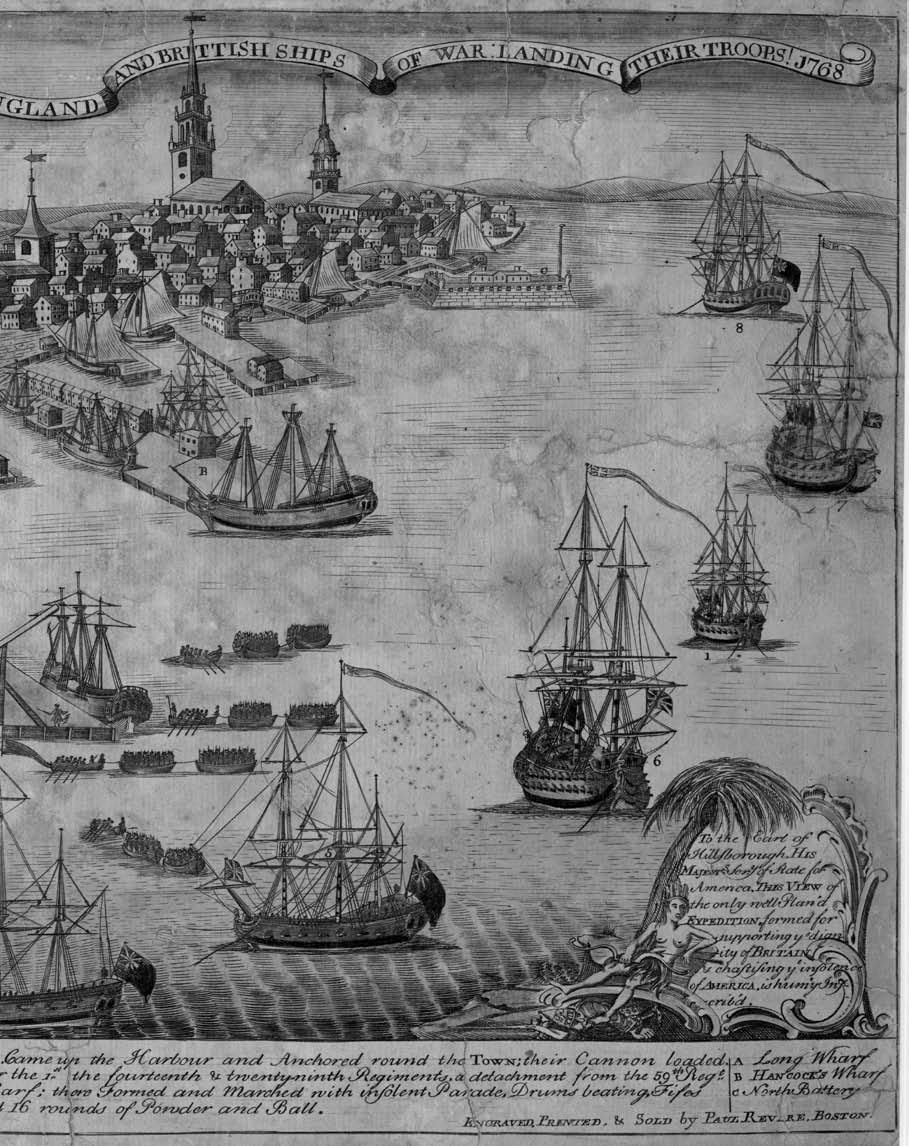

Hulton would never be beaten by street toughs, never be tarred and feathered by a mob. Others in the customs service—dozens of others—would not be so lucky. They suffered all of the pain and humiliation that accompanies such physical abuse.108 Hulton’s closest call came in June 1770, which prompted his second flight to Castle William. The first time had been two years before, in the aftermath of the Liberty incident. John Hancock owned the Liberty, a sloop engaged in the transatlantic trade. In the eyes of customs officials like Joseph Harrison, Boston’s collector, and Benjamin Hallowell, Boston’s comptroller, Hancock was nothing more than a successful smuggler. They looked for an excuse to go after him and the Liberty’s master provided it by unloading his cargo before he received proper clearance. They ordered that the sloop be seized. As it was being towed away from the dock by a British warship a crowd set upon them when they were foolish enough to linger too long at the scene. Bloodied and frightened, they fled to Castle William. Hulton and the board members—all except Temple—followed in short order, after first seeking sanctuary on the HMS Romney, then in the harbor.109 They entreated Governor Bernard to request that troops be dispatched to restore the peace and enable them to perform their duties.110 Customs officials, including Hulton and his colleagues on the board—again, except for Temple, who stood apart from them on this issue—would never be forgiven for that by leaders of the political opposition.111

Henry, with Elizabeth and Ann, did not leave Castle William until after the troops finally arrived in October. Hulton and his colleagues did their work there as best they could. Only Temple went back and forth to town with any regularity. He alone among them had left his family in Boston proper. With the troops’s coming, anti-board rhetoric intensified. Hulton was relieved to have soldiers about, although they did not act as a police force and “the temper of the people is not changed.”112 He could not yet know that their being in Boston would precipitate his second, even more precipitous, flight to the Castle. The only incident that had reached Henry and Elizabeth’s household before they moved to Brookline had occurred in May 1769. The house they were renting caught fire and Elizabeth, nearly nine months pregnant, called outside for help. Her servant and one from the neighbor’s put the fire out. No one else came to her aid and one woman passing by called out loudly, “it is only the Commissioner[’]s house, let it burn.”113 Once it became common knowledge that Hulton had bought Gridley’s estate the windows of the then empty house were broken.114 It would be many months after the family took possession until anything else happened.